Jews, Commerce, & Culture

Judaic Studies 2008-2009 Fellows at the University of Pennsylvania

Edgar Degas, At the Stock Exchange (1878-1879).

Ernest May, depicted here, was a successful businessman and collector of Degas' work, who later bequeathed this painting to the Louvre. Degas' portrait of his patron exemplifies the complex relationship between image and reality in the depiction of Jews in commerce.

Courtesy of the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France.

Introduction

Jewish economic history is both understudied and overrated. This paradox is not hard to explain: Jews' historically disproportionate role in commerce and finance has been a source of embarrassed silence for some scholars and eager exaggeration for others, largely depending on one's attitude to capitalism and readiness to associate it prominently with Jews.

The year at The Katz Center devoted to "Jews, Commerce and Culture" had the ambitious aim of reconstituting the study of Jews and economy on grounds that are less ideological and teleological. The emphasis on "commerce" aimed to defuse apologetics by confronting the most controversial feature of the Jews' economic past head on. Here the overarching question was whether and how commerce can serve as a useful category for linking local Jewish communities and events across a wide geographical and chronological expanse. At the same time, the prominence in the title given to "culture" was meant to underscore the truth that economics is not solely materialist and quantitative in nature but is rather an integral part of the larger fabric of Jewish religion and folkways.

The papers presented in the weekly seminars and concluding colloquium (a number of which are represented in this web exhibit) reflected this eclectic outlook. Studies of Jewish business failure sought to counteract - or at least complicate - prevailing stereotypes of inevitable commercial triumph; analyses of transnational philanthropic efforts exposed the complex interrelationship between Jewish commercial and communal networks; while explorations of Jews' consumption practices inverted the more typical focus on Jews as sellers. These and the other innovative approaches adopted during the year suggest that the moment is ripe to bring economic matters into closer alignment with Jewish Studies as a whole.

Jonathan Karp

Interested Parties: Thomas Aquinas, John Pacham, and Gerard of Aberville on Usury

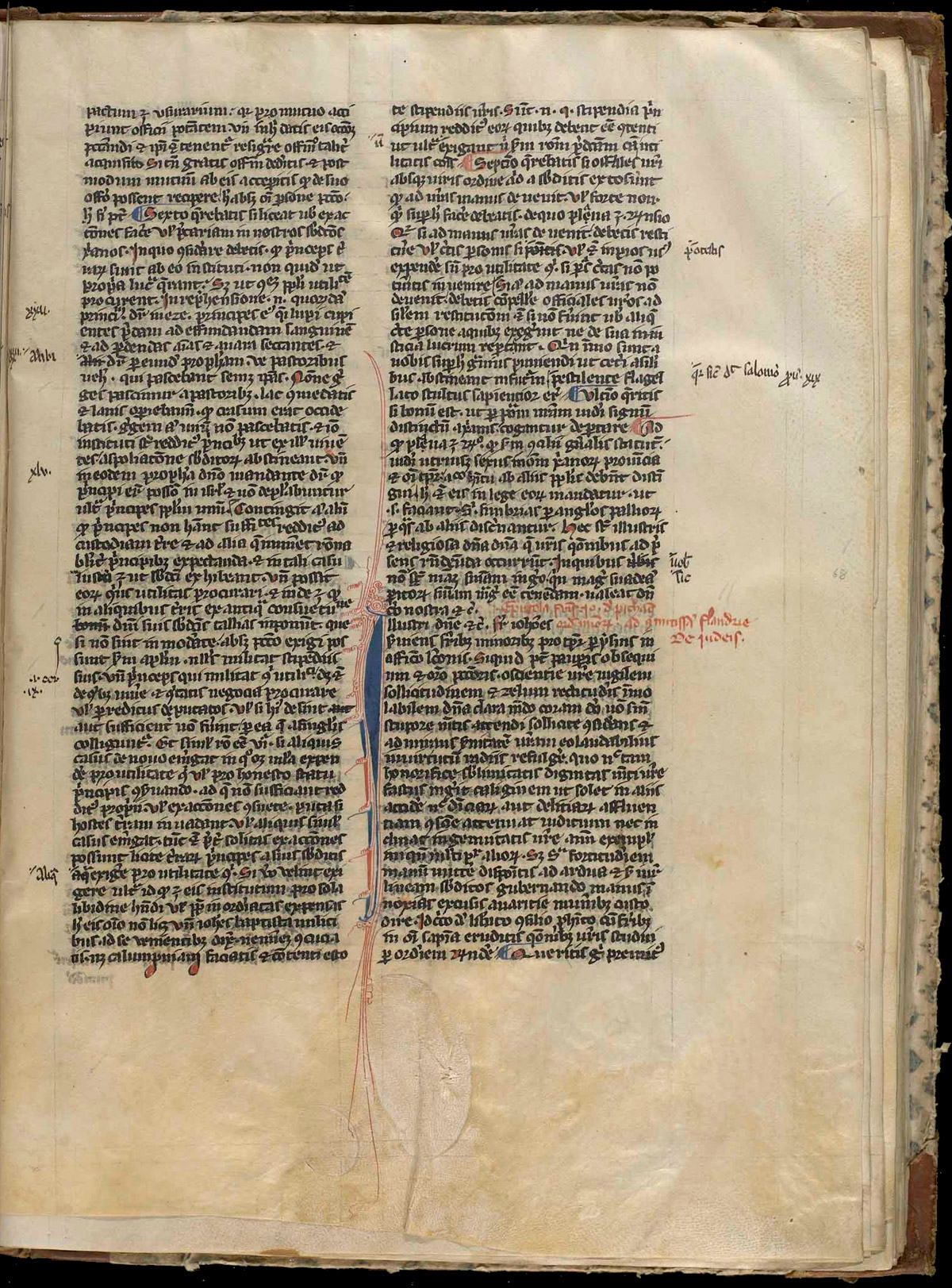

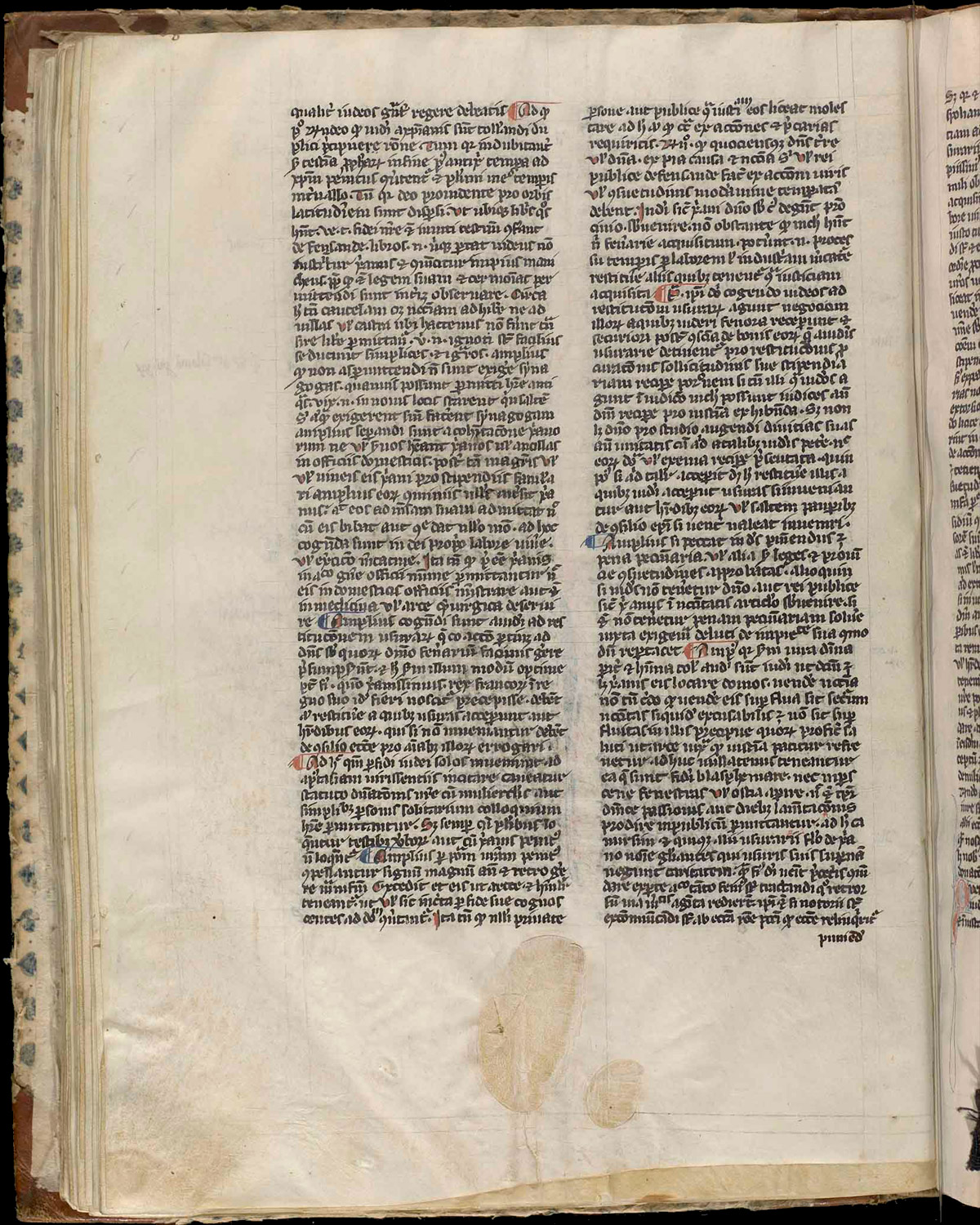

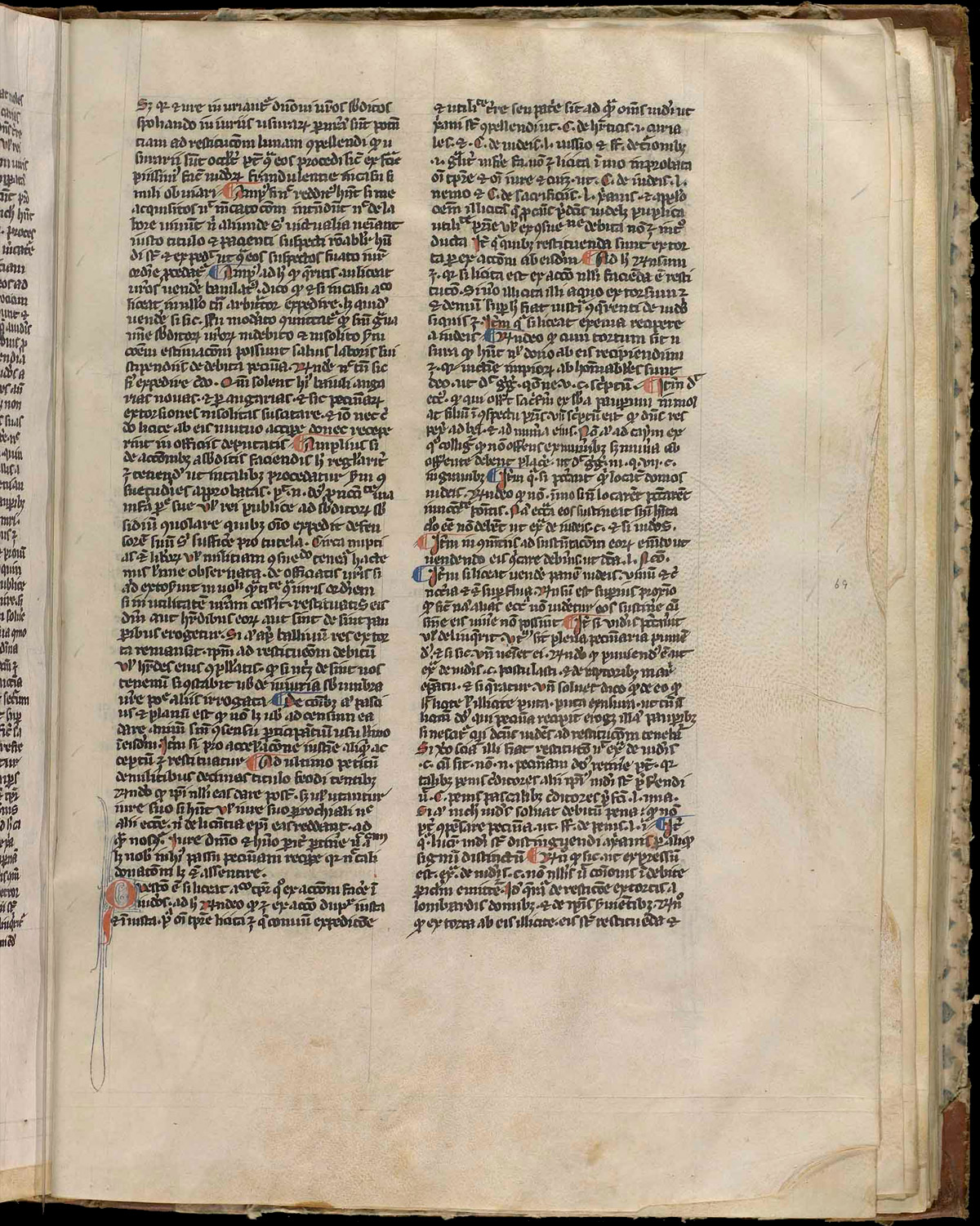

In the Fall of 2008, the Penn Libraries acquired a Latin codex of the turn of the 14th century (Ms. Codex 1271), a collection of short works by Thomas Aquinas [1225 - 1274]. It includes notably (fol. 68r - 69r) Thomas's letter to the countess of Brabant concerning the taxation of the Jews who allegedly gained their money through forbidden "usurious" operations. This letter has already been subject to much scholarly attention. However, attached to the newly acquired codex is another letter, unpublished, on the same subject by the famous Archbishop of Canterbury John Pacham (or: Peckham) [ca. 1230 -1292,] and yet another one by the little known Gerard of Aberville [d. 1272].

Interested Parties: Thomas Aquinas, John Pacham, and Gerard of Aberville on Usury

In the Fall of 2008, the Penn Libraries acquired a Latin codex of the turn of the 14th century (Ms. Codex 1271), a collection of short works by Thomas Aquinas [1225 - 1274]. It includes notably (fol. 68r - 69r) Thomas's letter to the countess of Brabant concerning the taxation of the Jews who allegedly gained their money through forbidden "usurious" operations. This letter has already been subject to much scholarly attention. However, attached to the newly acquired codex is another letter, unpublished, on the same subject by the famous Archbishop of Canterbury John Pacham (or: Peckham) [ca. 1230 -1292,] and yet another one by the little known Gerard of Aberville [d. 1272].

Interested Parties: Thomas Aquinas, John Pacham, and Gerard of Aberville on Usury

In the Fall of 2008, the Penn Libraries acquired a Latin codex of the turn of the 14th century (Ms. Codex 1271), a collection of short works by Thomas Aquinas [1225 - 1274]. It includes notably (fol. 68r - 69r) Thomas's letter to the countess of Brabant concerning the taxation of the Jews who allegedly gained their money through forbidden "usurious" operations. This letter has already been subject to much scholarly attention. However, attached to the newly acquired codex is another letter, unpublished, on the same subject by the famous Archbishop of Canterbury John Pacham (or: Peckham) [ca. 1230 -1292,] and yet another one by the little known Gerard of Aberville [d. 1272].

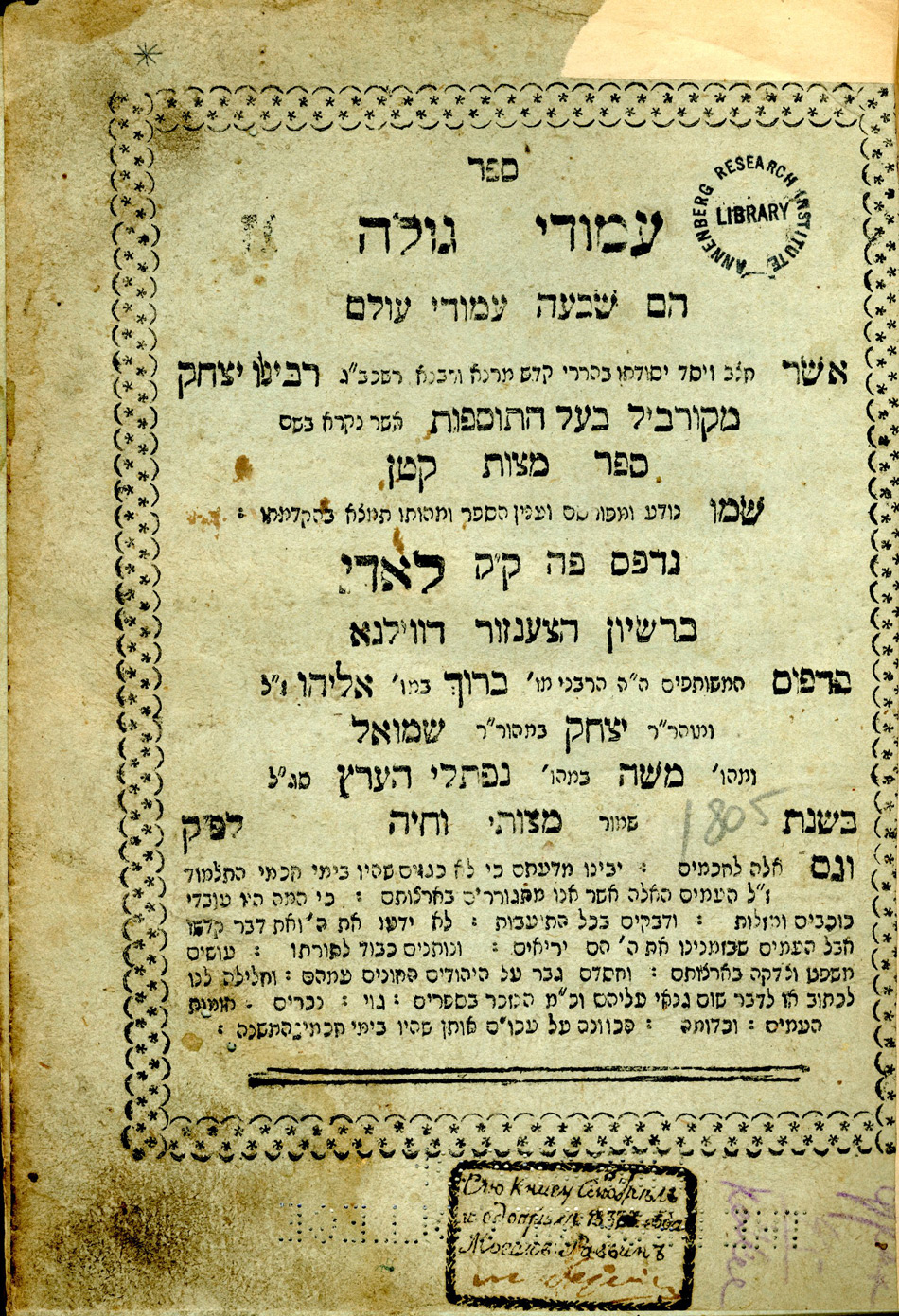

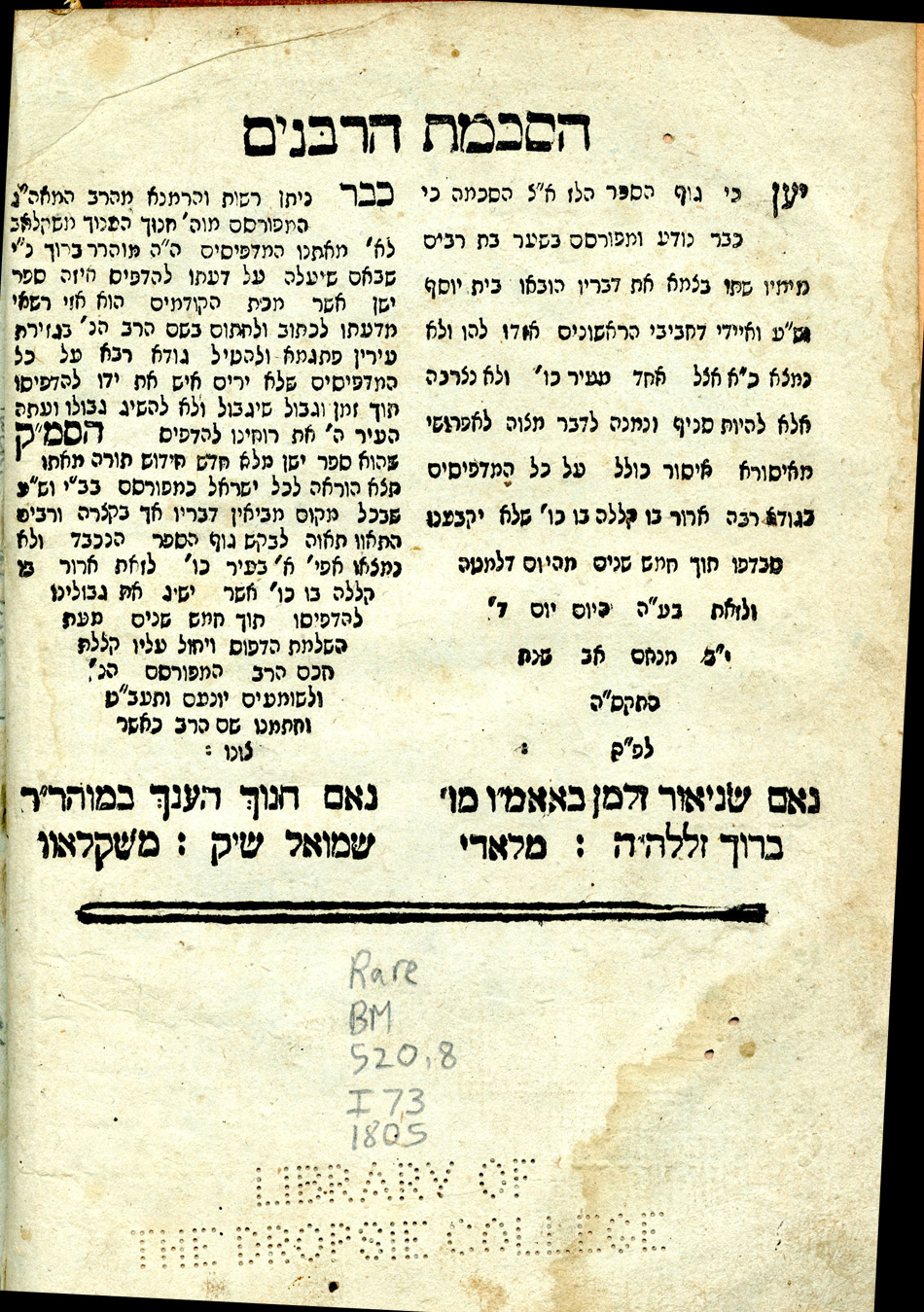

The Semak of Rabbi Isaac of Corbeil

R. Isaac of Corbeil authored his halakhic work the Amudei Gola (Pillars of Exile) popularly known as Semak (an acronym for Sefer Misvot Katan) circa 1276-1277. The raison d'être of the book was to strengthen religious observance of the commandments relevant to Jews living in the Diaspora. This was not a work written for scholars but rather one that whose purpose was to promote piety amongst the nation. In order to facilitate weekly study of his work he divided it into seven sections (pillars).

In a letter that Isaac circulated to the Jewish communities of France we learn how he acted to promote his book. He proposed that every community keep a copy of his work available for any one who wishes to copy it, even suggesting that they allocate funds that would allow the scribe to spend time in the community while copying the book. This is the only known example from medieval Ashkenaz of an author acting to promote his work. It is difficult to ascertain whether any community actually followed the dictates of the good Rabbi, nevertheless, it is quite clear that his book was one of the most popular halakhic books ever written in Northern France. Close to 200 medieval manuscripts survive till this day that bear witness to the immense popularity of the work.

The Semak of Rabbi Isaac of Corbeil

R. Isaac of Corbeil authored his halakhic work the Amudei Gola (Pillars of Exile) popularly known as Semak (an acronym for Sefer Misvot Katan) circa 1276-1277. The raison d'être of the book was to strengthen religious observance of the commandments relevant to Jews living in the Diaspora. This was not a work written for scholars but rather one that whose purpose was to promote piety amongst the nation. In order to facilitate weekly study of his work he divided it into seven sections (pillars).

In a letter that Isaac circulated to the Jewish communities of France we learn how he acted to promote his book. He proposed that every community keep a copy of his work available for any one who wishes to copy it, even suggesting that they allocate funds that would allow the scribe to spend time in the community while copying the book. This is the only known example from medieval Ashkenaz of an author acting to promote his work. It is difficult to ascertain whether any community actually followed the dictates of the good Rabbi, nevertheless, it is quite clear that his book was one of the most popular halakhic books ever written in Northern France. Close to 200 medieval manuscripts survive till this day that bear witness to the immense popularity of the work.

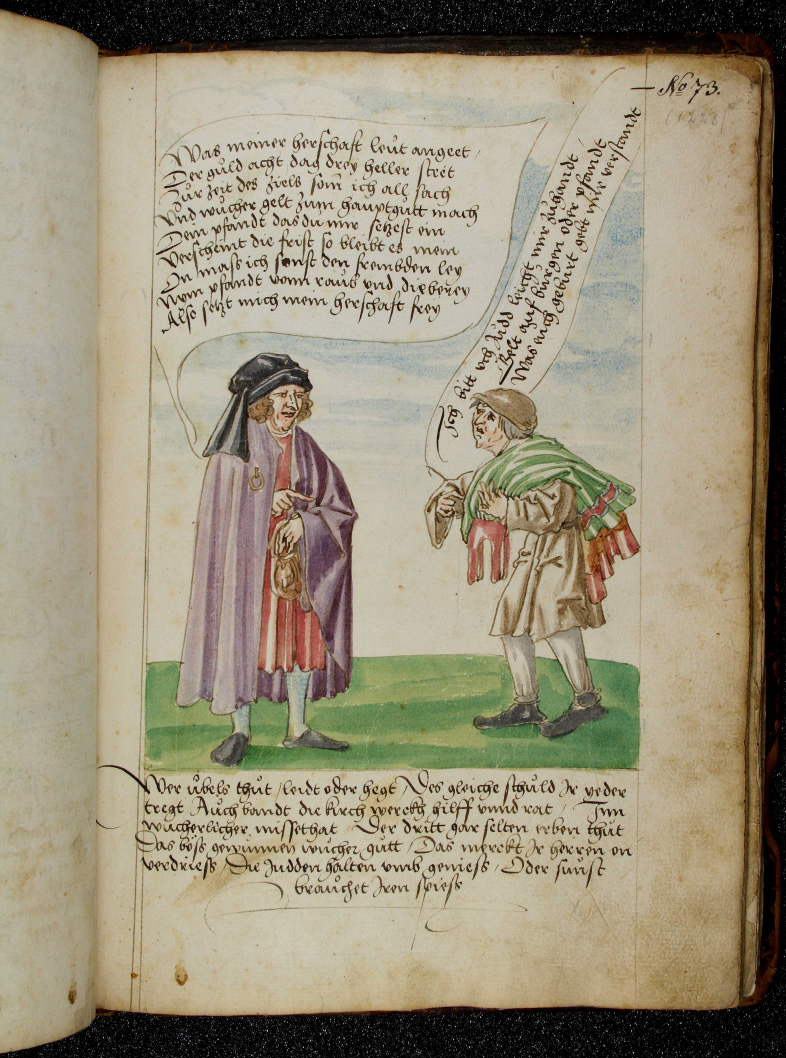

"Memorial der Tugend" by Johann von Schwarzenberg

This exquisitely crafted pen drawing comes from an early 16th century volume depicting edifying morality tales through episodes from the Bible and antique and medieval times. Here a peasant asks a Jew to lend him money against a pawn, inquiring about the interest, which by the Jew's own admission turns out to be horrendous. The bottom caption tells the moral of the story, with a clear invitation to the nobility to get rid of the Jewish plague, if need be by violence. It echoes a sentiment shared by many of this period, for instance the religious reformer Martin Luther:

"Whoever does wrong carries the same burden of guilt. Ill-begotten usurious gain is seldom inherited. Pay attention to this, you lords who hold Jews and enjoy the profit, or otherwise use your spear."

Rag Dealers and Pawnbrokers Have Their Place Too: The Start of Jewish Settlement in Livorno

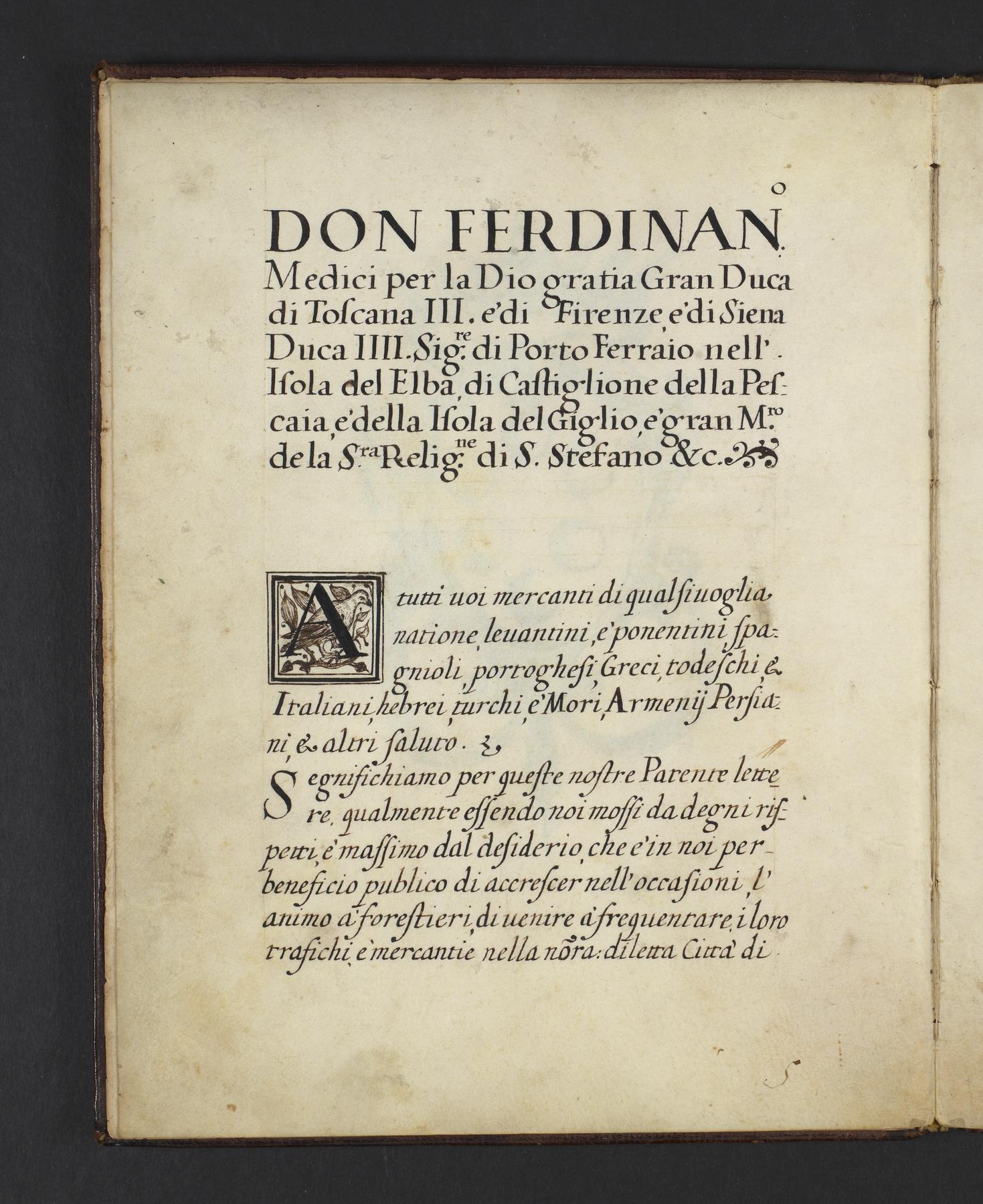

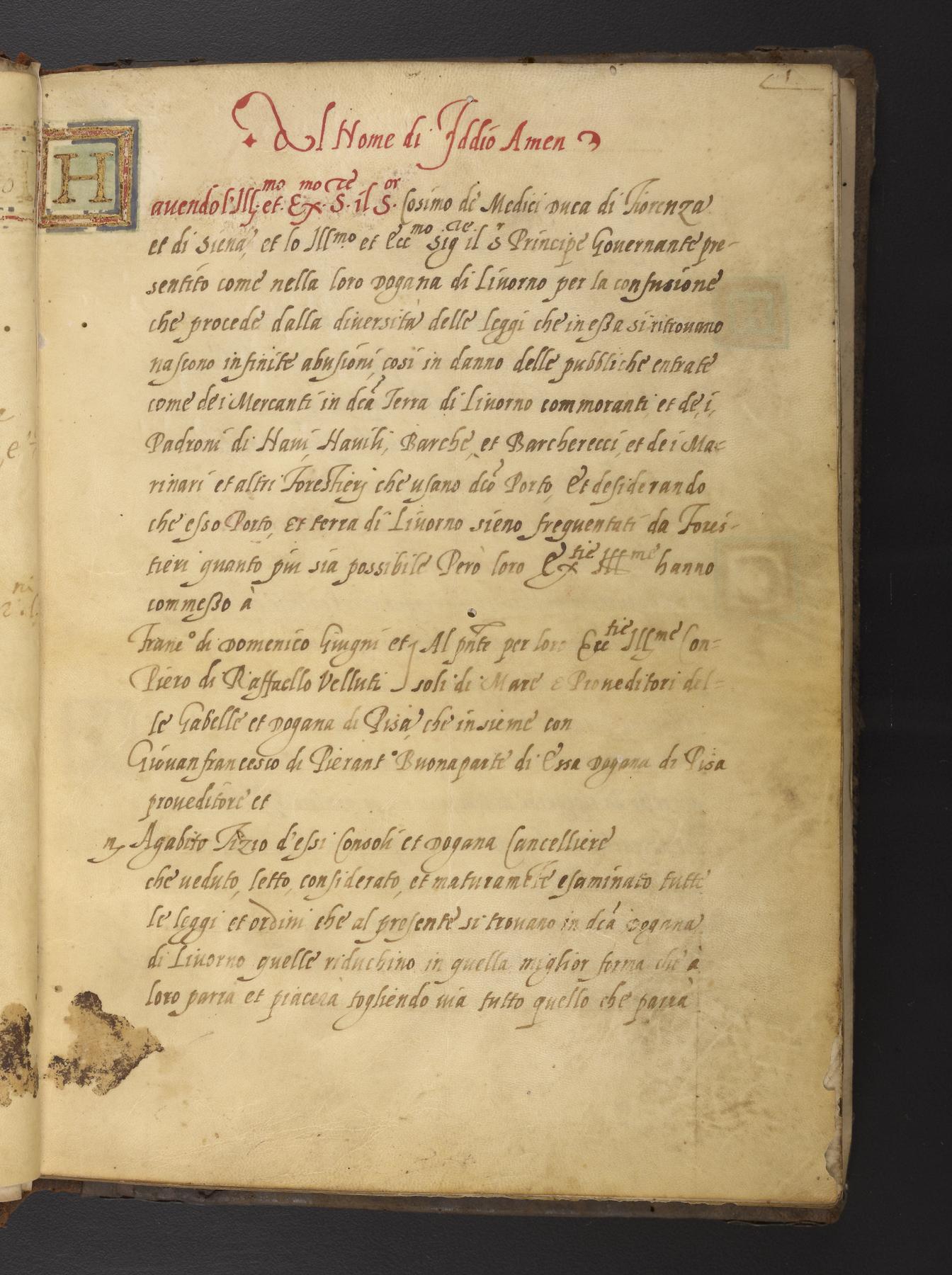

The port city of Livorno on the Tuscan coast was the home of arguably the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in Italy during the seventeenth century. Established by a special charter, the so-called Livornina, in 1593 (see image at left), the community was organized as a merchant "company." Subsidized by an enormous government loan, this corporation had special customs and tax privileges, its own recognized courts, and the right to admit (or refuse entry) to whomever it wished. The Medici rulers saw Jewish Sephardic merchants as a powerful force in Mediterranean trade and expected them to give Tuscany improved commercial access to the Ottoman Levant, Muslim North Africa, and (through converso relatives and contacts) the commercial network that radiated out from Spain and Portugal to encompass the entire globe.

Livorno was then little more than a fishing village, filled with sailors, soldiers, thieves and prostitutes, and surrounded by malarial marshes. The Medici were investing huge sums in the town and its port facilities because the older port at Pisa, a few miles up the coast, had silted up and become unusable for sea-going vessels. The Livornina charter (and the letters sent out to advertise it) clearly assume that the wealthy merchants would live in Pisa and use Livorno only as a shipping point. To everyone's surprise, however, it was Livorno that grew rapidly, and the Jewish community there soon outstripped its "mother colony" demanding jurisdictional and economic independence. While the growth of Livorno's Jewry was undoubtedly motivated by merchants' desire to live conveniently near the harbor, it seems that the younger community was initiated by quite a different group of settlers..

From the start it was clear that not all Jews were Sephardim (that is, of Iberian origin), nor were they all merchants. Italian Jewry of the era included many whose families had lived on the Peninsula for centuries, as well as thousands of recent immigrants from all over northern and western Europe. In many of the Italian states, government policy was becoming more restrictive towards Jews: outright expulsions or at least ghettoizations, were forcing Jews to move from place to place seeking haven and economic opportunity. Inevitably, some of these Jews appealed to the massari (communal stewards) in Pisa for admission, but the latter were unwilling to admit "undesirables" - that is, those likely to tarnish the image of Jews as wealthy and powerful merchants. Refused entry into the community of Pisa, some of these Jews appealed directly to the Medici for individual admission into Livorno.

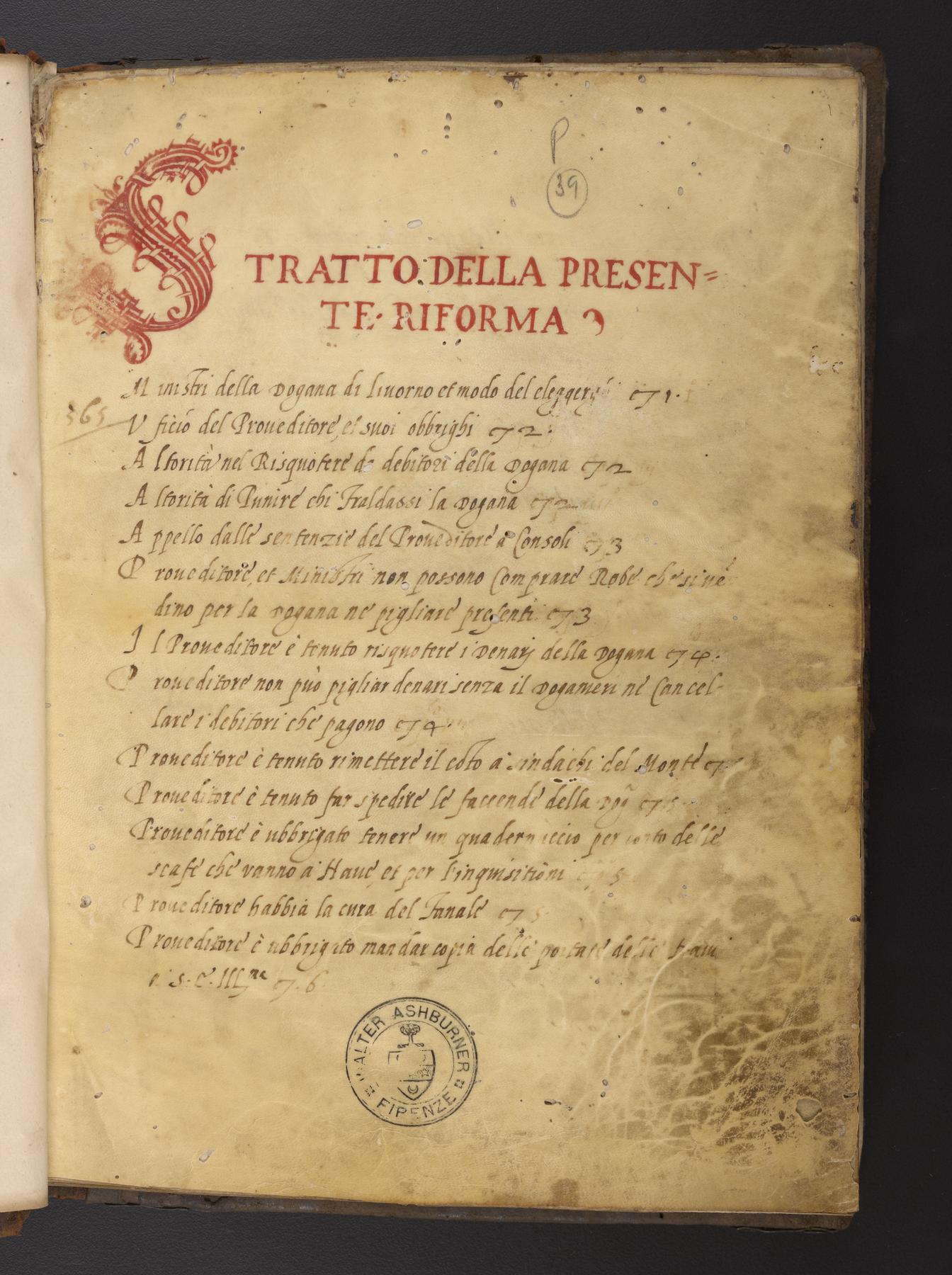

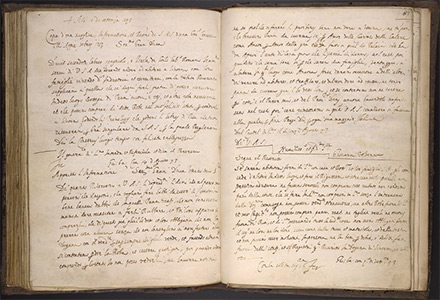

Displayed here are the title page, first page with benediction, and pages 82v-83r of a vellum manuscript, volume 1 of Codex 266, in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania. This volume was intended as the official reference copy of the Statuti della Dogana, the regulations of the customs house at Livorno, reformed in 1565. Blank pages were left at the end so that any important new ruling could be added.

One such ruling was issue in September of 1593 in answer to the petition by David Sacerdote, a Spanish Jew, and Isache de Goilo, a Jew from Rome, for permission to settle in Livorno with their families, to open a new- and used-clothing shop in the town, and to travel around the Medici state buying up used goods that they could sell in their shop. Asked for his opinion, the governor of Livorno responded positively, both as to the usefulness of the shop and as to the desirability of another two families coming to settle in the town, especially since they might attract others. He did have some worries, however. The shop might become an outlet for stolen property and so the Jews would have to agree to present any used item to the customs officials before putting it on sale. The trade in used items must not be used to cover a money-lending operation. The shop should not be allowed to trade in woolen cloths since that would compete with the recently licensed woolens manufacture in the city. Grand Duke Ferdinando agreed with the governor, licensing the shop under the general terms described (though restricting used clothing purchases to the area immediately around Pisa and Livorno), and freeing the partners and their wives from the obligation to wear the Jewish badge, from customs duties and taxes, and from prosecution for past debts incurred elsewhere. Thus the petitioners were granted almost all of the privileges of the Pisan community even though they were not part of it and had to be registered individually in Livorno.

Historians are often hesitant to describe the Jewish "rigattieri" and "straccieri" - the rag dealers and second-hand shopkeepers who were so much a feature of the Jewish economy in past centuries. By euphemistically and narrowly referring only to the wealthier "bankers," historians paint a picture of elegant financiers who are often also the cultural elite of their community. But Jewish "banks" were for the most part indistinguishable from what we now call pawnshops, serving, then as now, the marginal elements of society. This was a profitable, if risky and not particularly esteemed, profession, but it was one of the few available to Jews of sixteenth century Italy. It was the kind of activity that attracted Jews to the port of Livorno where a transient and often disreputable population often needed quick cash without too many questions asked. We can easily understand why wealthier Jewish merchants did not want to be associated with pawnbrokers and rag dealers. But government officials understood the economic need for such services, and in the frontier conditions of Livorno any settler, even a Jew, was to be valued. It was from such aggressive businessmen that the Jewish community of Livorno was to grow.

Rag Dealers and Pawnbrokers Have Their Place Too: The Start of Jewish Settlement in Livorno

The port city of Livorno on the Tuscan coast was the home of arguably the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in Italy during the seventeenth century. Established by a special charter, the so-called Livornina, in 1593 (see image at left), the community was organized as a merchant "company." Subsidized by an enormous government loan, this corporation had special customs and tax privileges, its own recognized courts, and the right to admit (or refuse entry) to whomever it wished. The Medici rulers saw Jewish Sephardic merchants as a powerful force in Mediterranean trade and expected them to give Tuscany improved commercial access to the Ottoman Levant, Muslim North Africa, and (through converso relatives and contacts) the commercial network that radiated out from Spain and Portugal to encompass the entire globe.

Livorno was then little more than a fishing village, filled with sailors, soldiers, thieves and prostitutes, and surrounded by malarial marshes. The Medici were investing huge sums in the town and its port facilities because the older port at Pisa, a few miles up the coast, had silted up and become unusable for sea-going vessels. The Livornina charter (and the letters sent out to advertise it) clearly assume that the wealthy merchants would live in Pisa and use Livorno only as a shipping point. To everyone's surprise, however, it was Livorno that grew rapidly, and the Jewish community there soon outstripped its "mother colony" demanding jurisdictional and economic independence. While the growth of Livorno's Jewry was undoubtedly motivated by merchants' desire to live conveniently near the harbor, it seems that the younger community was initiated by quite a different group of settlers..

From the start it was clear that not all Jews were Sephardim (that is, of Iberian origin), nor were they all merchants. Italian Jewry of the era included many whose families had lived on the Peninsula for centuries, as well as thousands of recent immigrants from all over northern and western Europe. In many of the Italian states, government policy was becoming more restrictive towards Jews: outright expulsions or at least ghettoizations, were forcing Jews to move from place to place seeking haven and economic opportunity. Inevitably, some of these Jews appealed to the massari (communal stewards) in Pisa for admission, but the latter were unwilling to admit "undesirables" - that is, those likely to tarnish the image of Jews as wealthy and powerful merchants. Refused entry into the community of Pisa, some of these Jews appealed directly to the Medici for individual admission into Livorno.

Displayed here are the title page, first page with benediction, and pages 82v-83r of a vellum manuscript, volume 1 of Codex 266, in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania. This volume was intended as the official reference copy of the Statuti della Dogana, the regulations of the customs house at Livorno, reformed in 1565. Blank pages were left at the end so that any important new ruling could be added.

One such ruling was issue in September of 1593 in answer to the petition by David Sacerdote, a Spanish Jew, and Isache de Goilo, a Jew from Rome, for permission to settle in Livorno with their families, to open a new- and used-clothing shop in the town, and to travel around the Medici state buying up used goods that they could sell in their shop. Asked for his opinion, the governor of Livorno responded positively, both as to the usefulness of the shop and as to the desirability of another two families coming to settle in the town, especially since they might attract others. He did have some worries, however. The shop might become an outlet for stolen property and so the Jews would have to agree to present any used item to the customs officials before putting it on sale. The trade in used items must not be used to cover a money-lending operation. The shop should not be allowed to trade in woolen cloths since that would compete with the recently licensed woolens manufacture in the city. Grand Duke Ferdinando agreed with the governor, licensing the shop under the general terms described (though restricting used clothing purchases to the area immediately around Pisa and Livorno), and freeing the partners and their wives from the obligation to wear the Jewish badge, from customs duties and taxes, and from prosecution for past debts incurred elsewhere. Thus the petitioners were granted almost all of the privileges of the Pisan community even though they were not part of it and had to be registered individually in Livorno.

Historians are often hesitant to describe the Jewish "rigattieri" and "straccieri" - the rag dealers and second-hand shopkeepers who were so much a feature of the Jewish economy in past centuries. By euphemistically and narrowly referring only to the wealthier "bankers," historians paint a picture of elegant financiers who are often also the cultural elite of their community. But Jewish "banks" were for the most part indistinguishable from what we now call pawnshops, serving, then as now, the marginal elements of society. This was a profitable, if risky and not particularly esteemed, profession, but it was one of the few available to Jews of sixteenth century Italy. It was the kind of activity that attracted Jews to the port of Livorno where a transient and often disreputable population often needed quick cash without too many questions asked. We can easily understand why wealthier Jewish merchants did not want to be associated with pawnbrokers and rag dealers. But government officials understood the economic need for such services, and in the frontier conditions of Livorno any settler, even a Jew, was to be valued. It was from such aggressive businessmen that the Jewish community of Livorno was to grow.

Rag Dealers and Pawnbrokers Have Their Place Too: The Start of Jewish Settlement in Livorno

The port city of Livorno on the Tuscan coast was the home of arguably the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in Italy during the seventeenth century. Established by a special charter, the so-called Livornina, in 1593 (see image at left), the community was organized as a merchant "company." Subsidized by an enormous government loan, this corporation had special customs and tax privileges, its own recognized courts, and the right to admit (or refuse entry) to whomever it wished. The Medici rulers saw Jewish Sephardic merchants as a powerful force in Mediterranean trade and expected them to give Tuscany improved commercial access to the Ottoman Levant, Muslim North Africa, and (through converso relatives and contacts) the commercial network that radiated out from Spain and Portugal to encompass the entire globe.

Livorno was then little more than a fishing village, filled with sailors, soldiers, thieves and prostitutes, and surrounded by malarial marshes. The Medici were investing huge sums in the town and its port facilities because the older port at Pisa, a few miles up the coast, had silted up and become unusable for sea-going vessels. The Livornina charter (and the letters sent out to advertise it) clearly assume that the wealthy merchants would live in Pisa and use Livorno only as a shipping point. To everyone's surprise, however, it was Livorno that grew rapidly, and the Jewish community there soon outstripped its "mother colony" demanding jurisdictional and economic independence. While the growth of Livorno's Jewry was undoubtedly motivated by merchants' desire to live conveniently near the harbor, it seems that the younger community was initiated by quite a different group of settlers..

From the start it was clear that not all Jews were Sephardim (that is, of Iberian origin), nor were they all merchants. Italian Jewry of the era included many whose families had lived on the Peninsula for centuries, as well as thousands of recent immigrants from all over northern and western Europe. In many of the Italian states, government policy was becoming more restrictive towards Jews: outright expulsions or at least ghettoizations, were forcing Jews to move from place to place seeking haven and economic opportunity. Inevitably, some of these Jews appealed to the massari (communal stewards) in Pisa for admission, but the latter were unwilling to admit "undesirables" - that is, those likely to tarnish the image of Jews as wealthy and powerful merchants. Refused entry into the community of Pisa, some of these Jews appealed directly to the Medici for individual admission into Livorno.

Displayed here are the title page, first page with benediction, and pages 82v-83r of a vellum manuscript, volume 1 of Codex 266, in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania. This volume was intended as the official reference copy of the Statuti della Dogana, the regulations of the customs house at Livorno, reformed in 1565. Blank pages were left at the end so that any important new ruling could be added.

One such ruling was issue in September of 1593 in answer to the petition by David Sacerdote, a Spanish Jew, and Isache de Goilo, a Jew from Rome, for permission to settle in Livorno with their families, to open a new- and used-clothing shop in the town, and to travel around the Medici state buying up used goods that they could sell in their shop. Asked for his opinion, the governor of Livorno responded positively, both as to the usefulness of the shop and as to the desirability of another two families coming to settle in the town, especially since they might attract others. He did have some worries, however. The shop might become an outlet for stolen property and so the Jews would have to agree to present any used item to the customs officials before putting it on sale. The trade in used items must not be used to cover a money-lending operation. The shop should not be allowed to trade in woolen cloths since that would compete with the recently licensed woolens manufacture in the city. Grand Duke Ferdinando agreed with the governor, licensing the shop under the general terms described (though restricting used clothing purchases to the area immediately around Pisa and Livorno), and freeing the partners and their wives from the obligation to wear the Jewish badge, from customs duties and taxes, and from prosecution for past debts incurred elsewhere. Thus the petitioners were granted almost all of the privileges of the Pisan community even though they were not part of it and had to be registered individually in Livorno.

Historians are often hesitant to describe the Jewish "rigattieri" and "straccieri" - the rag dealers and second-hand shopkeepers who were so much a feature of the Jewish economy in past centuries. By euphemistically and narrowly referring only to the wealthier "bankers," historians paint a picture of elegant financiers who are often also the cultural elite of their community. But Jewish "banks" were for the most part indistinguishable from what we now call pawnshops, serving, then as now, the marginal elements of society. This was a profitable, if risky and not particularly esteemed, profession, but it was one of the few available to Jews of sixteenth century Italy. It was the kind of activity that attracted Jews to the port of Livorno where a transient and often disreputable population often needed quick cash without too many questions asked. We can easily understand why wealthier Jewish merchants did not want to be associated with pawnbrokers and rag dealers. But government officials understood the economic need for such services, and in the frontier conditions of Livorno any settler, even a Jew, was to be valued. It was from such aggressive businessmen that the Jewish community of Livorno was to grow.

Rag Dealers and Pawnbrokers Have Their Place Too: The Start of Jewish Settlement in Livorno

The port city of Livorno on the Tuscan coast was the home of arguably the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in Italy during the seventeenth century. Established by a special charter, the so-called Livornina, in 1593 (see image at left), the community was organized as a merchant "company." Subsidized by an enormous government loan, this corporation had special customs and tax privileges, its own recognized courts, and the right to admit (or refuse entry) to whomever it wished. The Medici rulers saw Jewish Sephardic merchants as a powerful force in Mediterranean trade and expected them to give Tuscany improved commercial access to the Ottoman Levant, Muslim North Africa, and (through converso relatives and contacts) the commercial network that radiated out from Spain and Portugal to encompass the entire globe.

Livorno was then little more than a fishing village, filled with sailors, soldiers, thieves and prostitutes, and surrounded by malarial marshes. The Medici were investing huge sums in the town and its port facilities because the older port at Pisa, a few miles up the coast, had silted up and become unusable for sea-going vessels. The Livornina charter (and the letters sent out to advertise it) clearly assume that the wealthy merchants would live in Pisa and use Livorno only as a shipping point. To everyone's surprise, however, it was Livorno that grew rapidly, and the Jewish community there soon outstripped its "mother colony" demanding jurisdictional and economic independence. While the growth of Livorno's Jewry was undoubtedly motivated by merchants' desire to live conveniently near the harbor, it seems that the younger community was initiated by quite a different group of settlers..

From the start it was clear that not all Jews were Sephardim (that is, of Iberian origin), nor were they all merchants. Italian Jewry of the era included many whose families had lived on the Peninsula for centuries, as well as thousands of recent immigrants from all over northern and western Europe. In many of the Italian states, government policy was becoming more restrictive towards Jews: outright expulsions or at least ghettoizations, were forcing Jews to move from place to place seeking haven and economic opportunity. Inevitably, some of these Jews appealed to the massari (communal stewards) in Pisa for admission, but the latter were unwilling to admit "undesirables" - that is, those likely to tarnish the image of Jews as wealthy and powerful merchants. Refused entry into the community of Pisa, some of these Jews appealed directly to the Medici for individual admission into Livorno.

Displayed here are the title page, first page with benediction, and pages 82v-83r of a vellum manuscript, volume 1 of Codex 266, in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania. This volume was intended as the official reference copy of the Statuti della Dogana, the regulations of the customs house at Livorno, reformed in 1565. Blank pages were left at the end so that any important new ruling could be added.

One such ruling was issue in September of 1593 in answer to the petition by David Sacerdote, a Spanish Jew, and Isache de Goilo, a Jew from Rome, for permission to settle in Livorno with their families, to open a new- and used-clothing shop in the town, and to travel around the Medici state buying up used goods that they could sell in their shop. Asked for his opinion, the governor of Livorno responded positively, both as to the usefulness of the shop and as to the desirability of another two families coming to settle in the town, especially since they might attract others. He did have some worries, however. The shop might become an outlet for stolen property and so the Jews would have to agree to present any used item to the customs officials before putting it on sale. The trade in used items must not be used to cover a money-lending operation. The shop should not be allowed to trade in woolen cloths since that would compete with the recently licensed woolens manufacture in the city. Grand Duke Ferdinando agreed with the governor, licensing the shop under the general terms described (though restricting used clothing purchases to the area immediately around Pisa and Livorno), and freeing the partners and their wives from the obligation to wear the Jewish badge, from customs duties and taxes, and from prosecution for past debts incurred elsewhere. Thus the petitioners were granted almost all of the privileges of the Pisan community even though they were not part of it and had to be registered individually in Livorno.

Historians are often hesitant to describe the Jewish "rigattieri" and "straccieri" - the rag dealers and second-hand shopkeepers who were so much a feature of the Jewish economy in past centuries. By euphemistically and narrowly referring only to the wealthier "bankers," historians paint a picture of elegant financiers who are often also the cultural elite of their community. But Jewish "banks" were for the most part indistinguishable from what we now call pawnshops, serving, then as now, the marginal elements of society. This was a profitable, if risky and not particularly esteemed, profession, but it was one of the few available to Jews of sixteenth century Italy. It was the kind of activity that attracted Jews to the port of Livorno where a transient and often disreputable population often needed quick cash without too many questions asked. We can easily understand why wealthier Jewish merchants did not want to be associated with pawnbrokers and rag dealers. But government officials understood the economic need for such services, and in the frontier conditions of Livorno any settler, even a Jew, was to be valued. It was from such aggressive businessmen that the Jewish community of Livorno was to grow.

Transnational Philanthropic Systems in the Early Modern Jewish World: The Eastern European Jewish Refugee Crisis of the Mid-Seventeenth Century

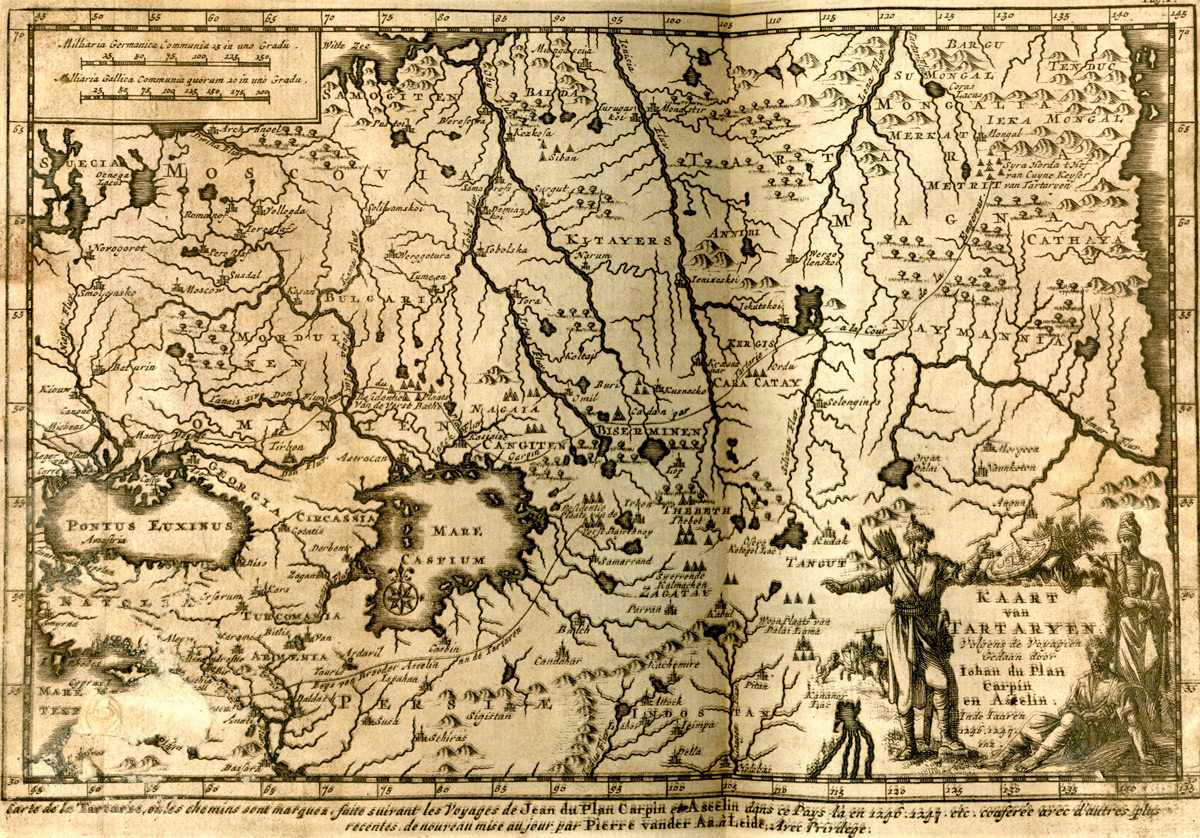

When the Tatar forces - as depicted here in this early 18th century anthology of travel writing in French - crossed the Dniepr river to join the Cossack armies in their uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1648, they set in motion a chain of events which would eventually change the map of Europe. One aspect of this was the fate of Eastern European Jewry. In the face of the massacres perpetrated first by the Cossack-Tatar forces, and later by the Swedish and Muscovite armies, many thousands of Jews fled, creating a wave of refugees not only within the Commonwealth, but also in Central and Western Europe and in the Mediterranean basin.

In order to help alleviate this problem, existing regional and intra-regional philanthropic systems came into play. The Lithuanian Jewish council coordinated efforts of the communities which comprised it to help settle the refugees, particularly the elderly, women and children, and to provide them with food, shelter and an income. Vienna acted as a central clearing house for the refugees in central Europe, not only giving them a place to stay but presiding over efforts to raise money for the collapsing Jewish communities of eastern Europe.

The Eastern European Jewish refugees in the Mediterranean basin, which included a high proportion of women, were largely swept up in the huge slave trade of the region. In the mid-seventeenth century, Jewish ransoming activities were conducted according to an agreement between the communities of Venice, Livorno, and Istanbul. This agreement collapsed in the face of the wave of refugees, whose representatives found themselves in competition with those ransoming other Jewish captives and those raising money for the Jewish poor of the Land of Israel. The lion's share of the costs of ransoming the eastern European Jews seem to have been borne by the Jews of Istanbul - a huge financial burden whose effects may have been felt for generations. In contrast, the Jews of eastern Europe managed to reconstruct their lives and their communities relatively quickly, thanks to their close co-operation with the enormously wealthy Polish magnates.

As the refugee crisis drew to an end, some Jews chose to return home to Poland-Lithuania, while others, particularly women, fearful of the dangers of travel, chose to remain where they were and start a new life. The spreading of the Polish-Lithuanian Jewish refugees as far afield as the eastern Mediterranean, the Maghreb, Central Europe and the Atlantic seaboard raised a great deal of interest among the Jewish population already settled there. This acted as a stimulus to Jewish publishing in both Hebrew and Yiddish.

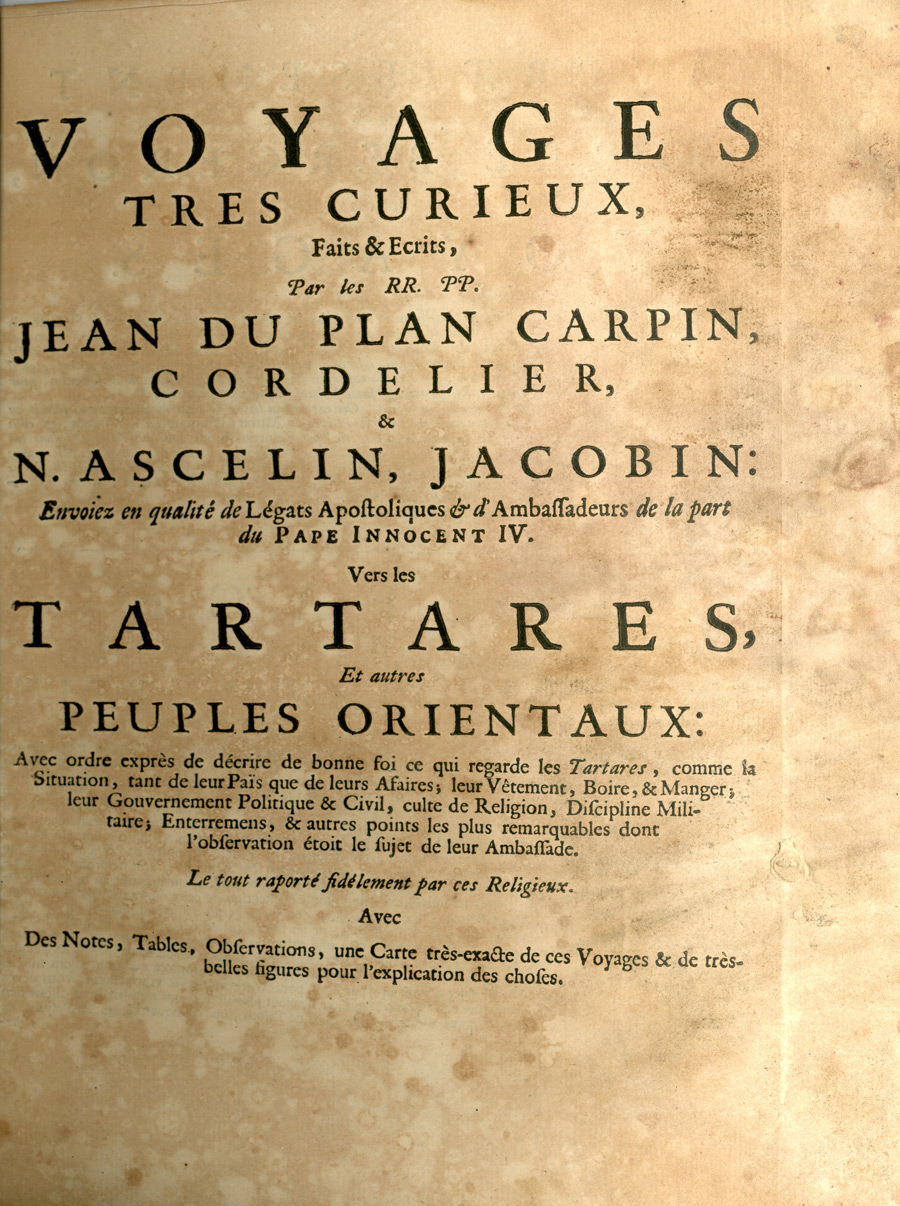

In somewhat similar fashion, the great geographical discoveries of the early modern era and Europe's colonial expansion created a thirst for knowledge about distant places and peoples in many European countries. In response, anthologies of travel literature became a highly popular genre. The images shown here illustrate one such travel anthology - Voyages faits principalement en Asie dans les XII, XIII, XIV, et XV siecles, published by Pieter van der Aa, La Haye 1735. This book reprinted the work of the seventeenth century French geographer, Pierre de Bergeron (1580-1657), who translated into French a number of travel narratives (including that of the Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela). The images shown here illustrated a text entitled, l'Histoire des Mongols appelés par nous Tartares, description des coutumes, de la géographie, de l'histoire et des figures marquantes du peuple mongol, which was originally written by the Papal legate to the Mongol Khans, Giovanni dal Piano dei Carpini (in French, Jean du Plan Carpin) in the thirteenth century.

Transnational Philanthropic Systems in the Early Modern Jewish World: The Eastern European Jewish Refugee Crisis of the Mid-Seventeenth Century

When the Tatar forces - as depicted here in this early 18th century anthology of travel writing in French - crossed the Dniepr river to join the Cossack armies in their uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1648, they set in motion a chain of events which would eventually change the map of Europe. One aspect of this was the fate of Eastern European Jewry. In the face of the massacres perpetrated first by the Cossack-Tatar forces, and later by the Swedish and Muscovite armies, many thousands of Jews fled, creating a wave of refugees not only within the Commonwealth, but also in Central and Western Europe and in the Mediterranean basin.

In order to help alleviate this problem, existing regional and intra-regional philanthropic systems came into play. The Lithuanian Jewish council coordinated efforts of the communities which comprised it to help settle the refugees, particularly the elderly, women and children, and to provide them with food, shelter and an income. Vienna acted as a central clearing house for the refugees in central Europe, not only giving them a place to stay but presiding over efforts to raise money for the collapsing Jewish communities of eastern Europe.

The Eastern European Jewish refugees in the Mediterranean basin, which included a high proportion of women, were largely swept up in the huge slave trade of the region. In the mid-seventeenth century, Jewish ransoming activities were conducted according to an agreement between the communities of Venice, Livorno, and Istanbul. This agreement collapsed in the face of the wave of refugees, whose representatives found themselves in competition with those ransoming other Jewish captives and those raising money for the Jewish poor of the Land of Israel. The lion's share of the costs of ransoming the eastern European Jews seem to have been borne by the Jews of Istanbul - a huge financial burden whose effects may have been felt for generations. In contrast, the Jews of eastern Europe managed to reconstruct their lives and their communities relatively quickly, thanks to their close co-operation with the enormously wealthy Polish magnates.

As the refugee crisis drew to an end, some Jews chose to return home to Poland-Lithuania, while others, particularly women, fearful of the dangers of travel, chose to remain where they were and start a new life. The spreading of the Polish-Lithuanian Jewish refugees as far afield as the eastern Mediterranean, the Maghreb, Central Europe and the Atlantic seaboard raised a great deal of interest among the Jewish population already settled there. This acted as a stimulus to Jewish publishing in both Hebrew and Yiddish.

In somewhat similar fashion, the great geographical discoveries of the early modern era and Europe's colonial expansion created a thirst for knowledge about distant places and peoples in many European countries. In response, anthologies of travel literature became a highly popular genre. The images shown here illustrate one such travel anthology - Voyages faits principalement en Asie dans les XII, XIII, XIV, et XV siecles, published by Pieter van der Aa, La Haye 1735. This book reprinted the work of the seventeenth century French geographer, Pierre de Bergeron (1580-1657), who translated into French a number of travel narratives (including that of the Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela). The images shown here illustrated a text entitled, l'Histoire des Mongols appelés par nous Tartares, description des coutumes, de la géographie, de l'histoire et des figures marquantes du peuple mongol, which was originally written by the Papal legate to the Mongol Khans, Giovanni dal Piano dei Carpini (in French, Jean du Plan Carpin) in the thirteenth century.

Transnational Philanthropic Systems in the Early Modern Jewish World: The Eastern European Jewish Refugee Crisis of the Mid-Seventeenth Century

When the Tatar forces - as depicted here in this early 18th century anthology of travel writing in French - crossed the Dniepr river to join the Cossack armies in their uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1648, they set in motion a chain of events which would eventually change the map of Europe. One aspect of this was the fate of Eastern European Jewry. In the face of the massacres perpetrated first by the Cossack-Tatar forces, and later by the Swedish and Muscovite armies, many thousands of Jews fled, creating a wave of refugees not only within the Commonwealth, but also in Central and Western Europe and in the Mediterranean basin.

In order to help alleviate this problem, existing regional and intra-regional philanthropic systems came into play. The Lithuanian Jewish council coordinated efforts of the communities which comprised it to help settle the refugees, particularly the elderly, women and children, and to provide them with food, shelter and an income. Vienna acted as a central clearing house for the refugees in central Europe, not only giving them a place to stay but presiding over efforts to raise money for the collapsing Jewish communities of eastern Europe.

The Eastern European Jewish refugees in the Mediterranean basin, which included a high proportion of women, were largely swept up in the huge slave trade of the region. In the mid-seventeenth century, Jewish ransoming activities were conducted according to an agreement between the communities of Venice, Livorno, and Istanbul. This agreement collapsed in the face of the wave of refugees, whose representatives found themselves in competition with those ransoming other Jewish captives and those raising money for the Jewish poor of the Land of Israel. The lion's share of the costs of ransoming the eastern European Jews seem to have been borne by the Jews of Istanbul - a huge financial burden whose effects may have been felt for generations. In contrast, the Jews of eastern Europe managed to reconstruct their lives and their communities relatively quickly, thanks to their close co-operation with the enormously wealthy Polish magnates.

As the refugee crisis drew to an end, some Jews chose to return home to Poland-Lithuania, while others, particularly women, fearful of the dangers of travel, chose to remain where they were and start a new life. The spreading of the Polish-Lithuanian Jewish refugees as far afield as the eastern Mediterranean, the Maghreb, Central Europe and the Atlantic seaboard raised a great deal of interest among the Jewish population already settled there. This acted as a stimulus to Jewish publishing in both Hebrew and Yiddish.

In somewhat similar fashion, the great geographical discoveries of the early modern era and Europe's colonial expansion created a thirst for knowledge about distant places and peoples in many European countries. In response, anthologies of travel literature became a highly popular genre. The images shown here illustrate one such travel anthology - Voyages faits principalement en Asie dans les XII, XIII, XIV, et XV siecles, published by Pieter van der Aa, La Haye 1735. This book reprinted the work of the seventeenth century French geographer, Pierre de Bergeron (1580-1657), who translated into French a number of travel narratives (including that of the Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela). The images shown here illustrated a text entitled, l'Histoire des Mongols appelés par nous Tartares, description des coutumes, de la géographie, de l'histoire et des figures marquantes du peuple mongol, which was originally written by the Papal legate to the Mongol Khans, Giovanni dal Piano dei Carpini (in French, Jean du Plan Carpin) in the thirteenth century.

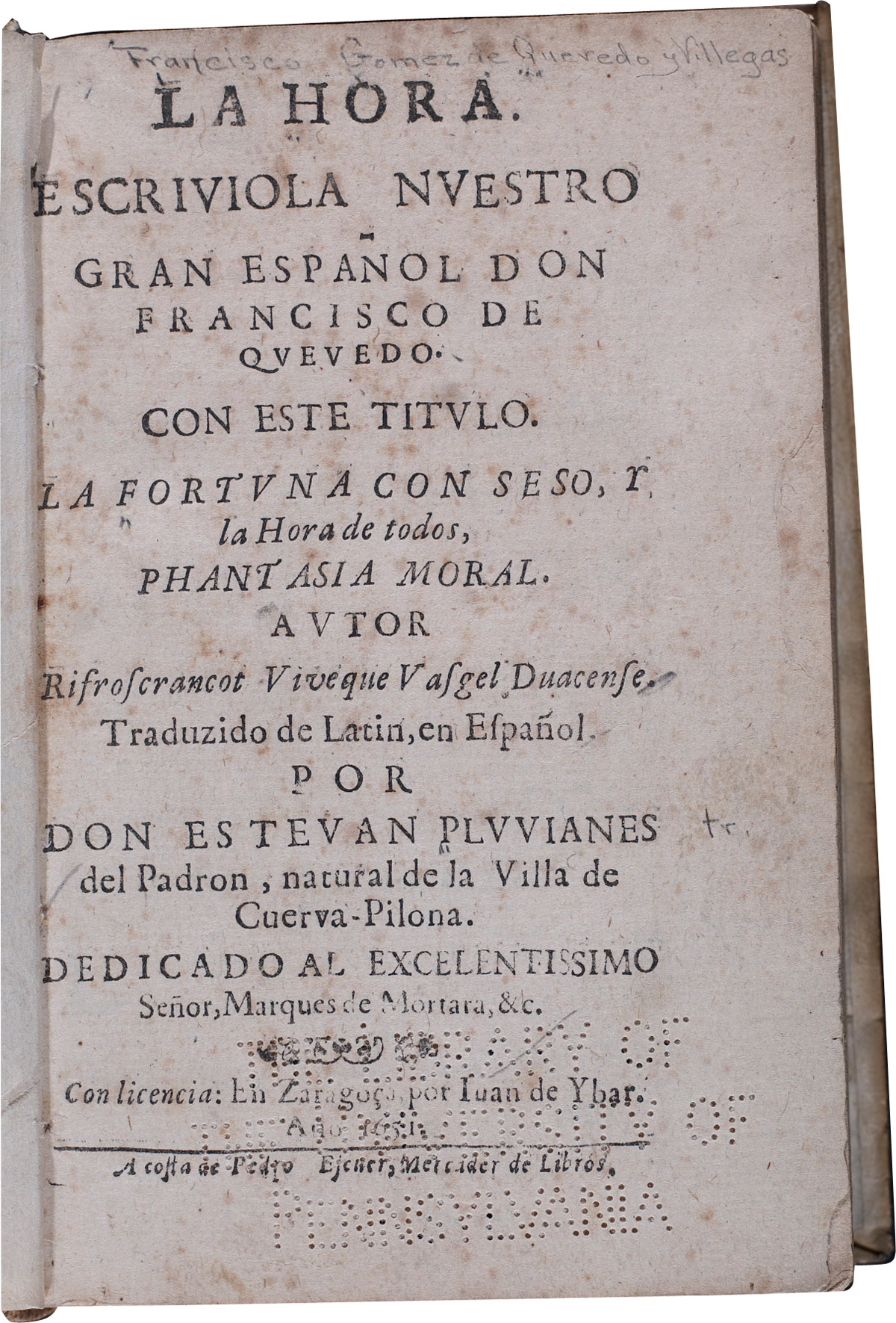

Don Francisco de Quevedo and the myth of Jewish world finance

In a chapter of his political satire called The Hour of All Men (La hora de todos), the Spanish classic Francisco de Quevedo invented around 1635 one of the central myths of modern anti-semitism: Jewish finance controls the world by means of the trans-national credit market. In this fanciful conspiracy plot, representatives of twelve major Jewish centers congregate in the Ottoman port of Salonica in order to receive a delegation of Machiavelian politicians from the Spanish government. Both sides agree to abolish Christianity and to replace it with the cult of money. The Jewish bankers vaunt that they have submitted the warfaring European powers by entangling them into an "indissoluble knot" of financial interdependence, in which Dutch fleets are armed with trading profits from Spain, and Spanish batallions raised with credit from Amsterdam stocks.

Quevedo superimposes a medieval religious stereotype to the unsettling economic realities created in the early seventeenth century by the first appearance of negotiable stocks, the stock exchange, central banks and a world wide trade in debts. The Portuguese Jewish merchants, whose dealings he satirizes, neither invented nor monopolized these instruments of financial rationality, but they used them at an early stage in the framework of what has been considered as the first global trading diaspora in modern history.

The Hour of All Men was printed under a pseudonym in 1650, the fifth edition, displayed here, being the first to mention the author's name. An English translation appeared in 1697.

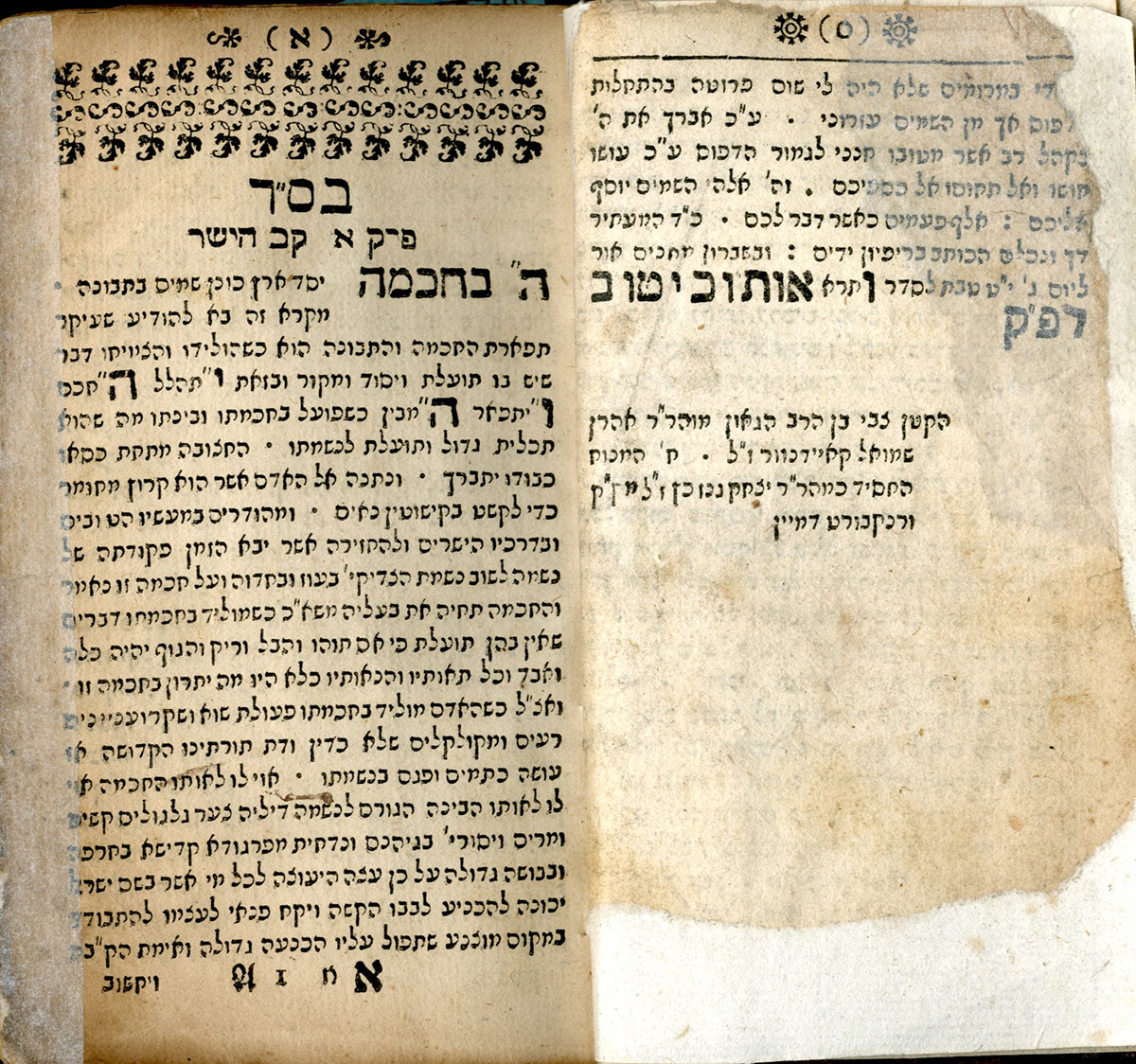

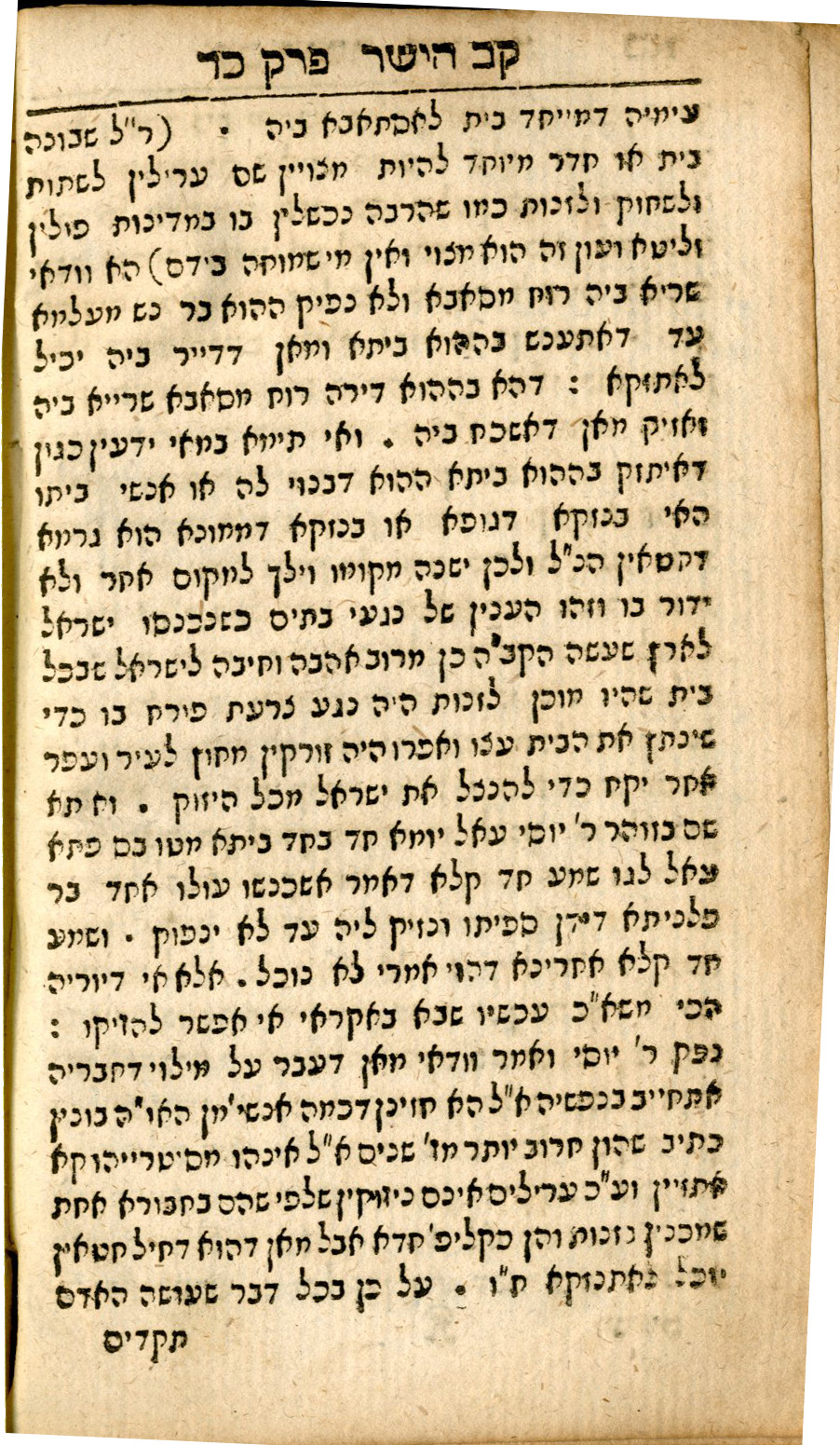

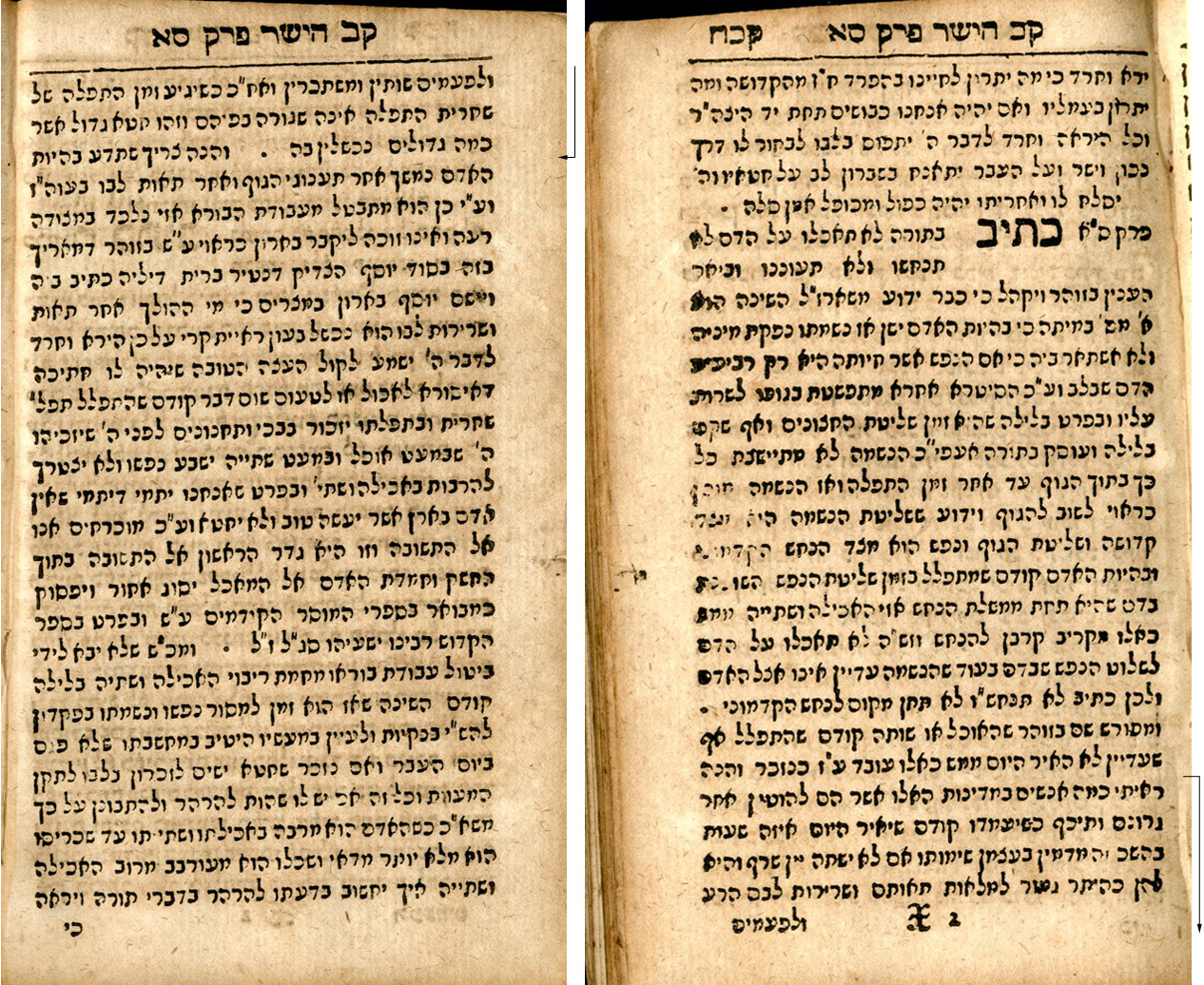

Jews and the Liquor Trade

These pages are excerpted from the first edition (Frankfurt, 1705) of Kav ha-yashar ("A Just Measure"), by Zvi Hirsch Koidanover (1655-1712). (Image, left, top, shows the author' introduction and the first page.) This enormously popular demonologically-charged mystical ethical book was reprinted dozens upon dozens of times in Hebrew, produced in a bilingual Hebrew and Yiddish version by the author, and eventually translated into Ladino. Many of its admonitions and Zoharic excerpts appear aimed at traveling merchants, warning of the ethical pitfalls they might encounter on their journeys. The small dimensions of the book would seem to confirm this authorial intent. Koidanover was born in Vilna and raised in Kurów (near Lublin). He moved to Nikolsburg (Moravia) after 1655 and then settled in Frankfurt am Main in 1667. He later returned to Vilna, where he prospered but was imprisoned. He returned permanently to Frankfurt in 1696. His observations thus reflect the inner life of Jews in the Polish, Czech, and German lands.

The pages reproduced here reflect the fascinating relationship between Jews and alcohol. By the end of the eighteenth century about 80 percent of rural Jews in Poland-Lithuania were involved in the sale and production of liquor. According to available data, Jews comprised 94 percent of urban and at least 78.7 percent of rural tavern keepers among seven towns and fifty-one villages in Bielsk County (Podlaskie District) during this period. A centerpiece of the reform initiatives of the Prussian, Russian, and Austrian monarchs who annexed the Polish lands during this period was the elimination of the rural Jewish liquor trade, which they attempted by means of escalating concession fees and outright expulsions. Surprisingly, few rabbinic or Hasidic leaders protested these draconian measures. It appears they themselves were uncomfortable with the tavern keeping profession. An excerpt from Kav ha-yashar (see images, left, middle) illustrates this ambivalence:

When one builds a house or designates a special room in one's house for the uncircumcised to come and drink, party, and fornicate, a common sin which many have committed in Poland and Lithuania, and which no one prohibits: In such a case the spirit of defilement will certainly settle upon the house and the one who built it will not leave this world until he is punished through that very house.

Why was the Polish nobility so inclined to lease its taverns and distilleries to Jews in the first place? Among the several explanations supplied by historians is the notion of Jewish sobriety: Jewish tavern keepers, in contrast to their Christian counterparts, tended not to drink up their profits. The following excerpt from Kav ha-yashar (see image, left, bottom) gives pause to such assumptions:

I have noticed that many people in this region are so enslaved to their appetites that immediately upon awakening, hours before dawn, they believe they will die if they do not drink liquor. And they think that it is perfectly permissible to indulge their lusts and stubborn hearts. And sometimes they drink to the point of intoxication. And afterwards, when the time of morning prayer arrives, their prayer is not fluent. And this is a terrible sin, which many luminaries have committed.

Nevertheless, we cannot conclude that alcoholism was a widespread problem in Jewish society. Such admonitions occur infrequently in ethical literature; while Slavic folk sayings reflect a widespread perception of Jewish sobriety during this period. There may still be something to the hypothesis!

Jews and the Liquor Trade

These pages are excerpted from the first edition (Frankfurt, 1705) of Kav ha-yashar ("A Just Measure"), by Zvi Hirsch Koidanover (1655-1712). (Image, left, top, shows the author' introduction and the first page.) This enormously popular demonologically-charged mystical ethical book was reprinted dozens upon dozens of times in Hebrew, produced in a bilingual Hebrew and Yiddish version by the author, and eventually translated into Ladino. Many of its admonitions and Zoharic excerpts appear aimed at traveling merchants, warning of the ethical pitfalls they might encounter on their journeys. The small dimensions of the book would seem to confirm this authorial intent. Koidanover was born in Vilna and raised in Kurów (near Lublin). He moved to Nikolsburg (Moravia) after 1655 and then settled in Frankfurt am Main in 1667. He later returned to Vilna, where he prospered but was imprisoned. He returned permanently to Frankfurt in 1696. His observations thus reflect the inner life of Jews in the Polish, Czech, and German lands.

The pages reproduced here reflect the fascinating relationship between Jews and alcohol. By the end of the eighteenth century about 80 percent of rural Jews in Poland-Lithuania were involved in the sale and production of liquor. According to available data, Jews comprised 94 percent of urban and at least 78.7 percent of rural tavern keepers among seven towns and fifty-one villages in Bielsk County (Podlaskie District) during this period. A centerpiece of the reform initiatives of the Prussian, Russian, and Austrian monarchs who annexed the Polish lands during this period was the elimination of the rural Jewish liquor trade, which they attempted by means of escalating concession fees and outright expulsions. Surprisingly, few rabbinic or Hasidic leaders protested these draconian measures. It appears they themselves were uncomfortable with the tavern keeping profession. An excerpt from Kav ha-yashar (see images, left, middle) illustrates this ambivalence:

When one builds a house or designates a special room in one's house for the uncircumcised to come and drink, party, and fornicate, a common sin which many have committed in Poland and Lithuania, and which no one prohibits: In such a case the spirit of defilement will certainly settle upon the house and the one who built it will not leave this world until he is punished through that very house.

Why was the Polish nobility so inclined to lease its taverns and distilleries to Jews in the first place? Among the several explanations supplied by historians is the notion of Jewish sobriety: Jewish tavern keepers, in contrast to their Christian counterparts, tended not to drink up their profits. The following excerpt from Kav ha-yashar (see image, left, bottom) gives pause to such assumptions:

I have noticed that many people in this region are so enslaved to their appetites that immediately upon awakening, hours before dawn, they believe they will die if they do not drink liquor. And they think that it is perfectly permissible to indulge their lusts and stubborn hearts. And sometimes they drink to the point of intoxication. And afterwards, when the time of morning prayer arrives, their prayer is not fluent. And this is a terrible sin, which many luminaries have committed.

Nevertheless, we cannot conclude that alcoholism was a widespread problem in Jewish society. Such admonitions occur infrequently in ethical literature; while Slavic folk sayings reflect a widespread perception of Jewish sobriety during this period. There may still be something to the hypothesis!

Jews and the Liquor Trade

These pages are excerpted from the first edition (Frankfurt, 1705) of Kav ha-yashar ("A Just Measure"), by Zvi Hirsch Koidanover (1655-1712). (Image, left, top, shows the author' introduction and the first page.) This enormously popular demonologically-charged mystical ethical book was reprinted dozens upon dozens of times in Hebrew, produced in a bilingual Hebrew and Yiddish version by the author, and eventually translated into Ladino. Many of its admonitions and Zoharic excerpts appear aimed at traveling merchants, warning of the ethical pitfalls they might encounter on their journeys. The small dimensions of the book would seem to confirm this authorial intent. Koidanover was born in Vilna and raised in Kurów (near Lublin). He moved to Nikolsburg (Moravia) after 1655 and then settled in Frankfurt am Main in 1667. He later returned to Vilna, where he prospered but was imprisoned. He returned permanently to Frankfurt in 1696. His observations thus reflect the inner life of Jews in the Polish, Czech, and German lands.

The pages reproduced here reflect the fascinating relationship between Jews and alcohol. By the end of the eighteenth century about 80 percent of rural Jews in Poland-Lithuania were involved in the sale and production of liquor. According to available data, Jews comprised 94 percent of urban and at least 78.7 percent of rural tavern keepers among seven towns and fifty-one villages in Bielsk County (Podlaskie District) during this period. A centerpiece of the reform initiatives of the Prussian, Russian, and Austrian monarchs who annexed the Polish lands during this period was the elimination of the rural Jewish liquor trade, which they attempted by means of escalating concession fees and outright expulsions. Surprisingly, few rabbinic or Hasidic leaders protested these draconian measures. It appears they themselves were uncomfortable with the tavern keeping profession. An excerpt from Kav ha-yashar (see images, left, middle) illustrates this ambivalence:

When one builds a house or designates a special room in one's house for the uncircumcised to come and drink, party, and fornicate, a common sin which many have committed in Poland and Lithuania, and which no one prohibits: In such a case the spirit of defilement will certainly settle upon the house and the one who built it will not leave this world until he is punished through that very house.

Why was the Polish nobility so inclined to lease its taverns and distilleries to Jews in the first place? Among the several explanations supplied by historians is the notion of Jewish sobriety: Jewish tavern keepers, in contrast to their Christian counterparts, tended not to drink up their profits. The following excerpt from Kav ha-yashar (see image, left, bottom) gives pause to such assumptions:

I have noticed that many people in this region are so enslaved to their appetites that immediately upon awakening, hours before dawn, they believe they will die if they do not drink liquor. And they think that it is perfectly permissible to indulge their lusts and stubborn hearts. And sometimes they drink to the point of intoxication. And afterwards, when the time of morning prayer arrives, their prayer is not fluent. And this is a terrible sin, which many luminaries have committed.

Nevertheless, we cannot conclude that alcoholism was a widespread problem in Jewish society. Such admonitions occur infrequently in ethical literature; while Slavic folk sayings reflect a widespread perception of Jewish sobriety during this period. There may still be something to the hypothesis!

In Dispute: Commerce, Commercial Courts, and Bills of Exchange

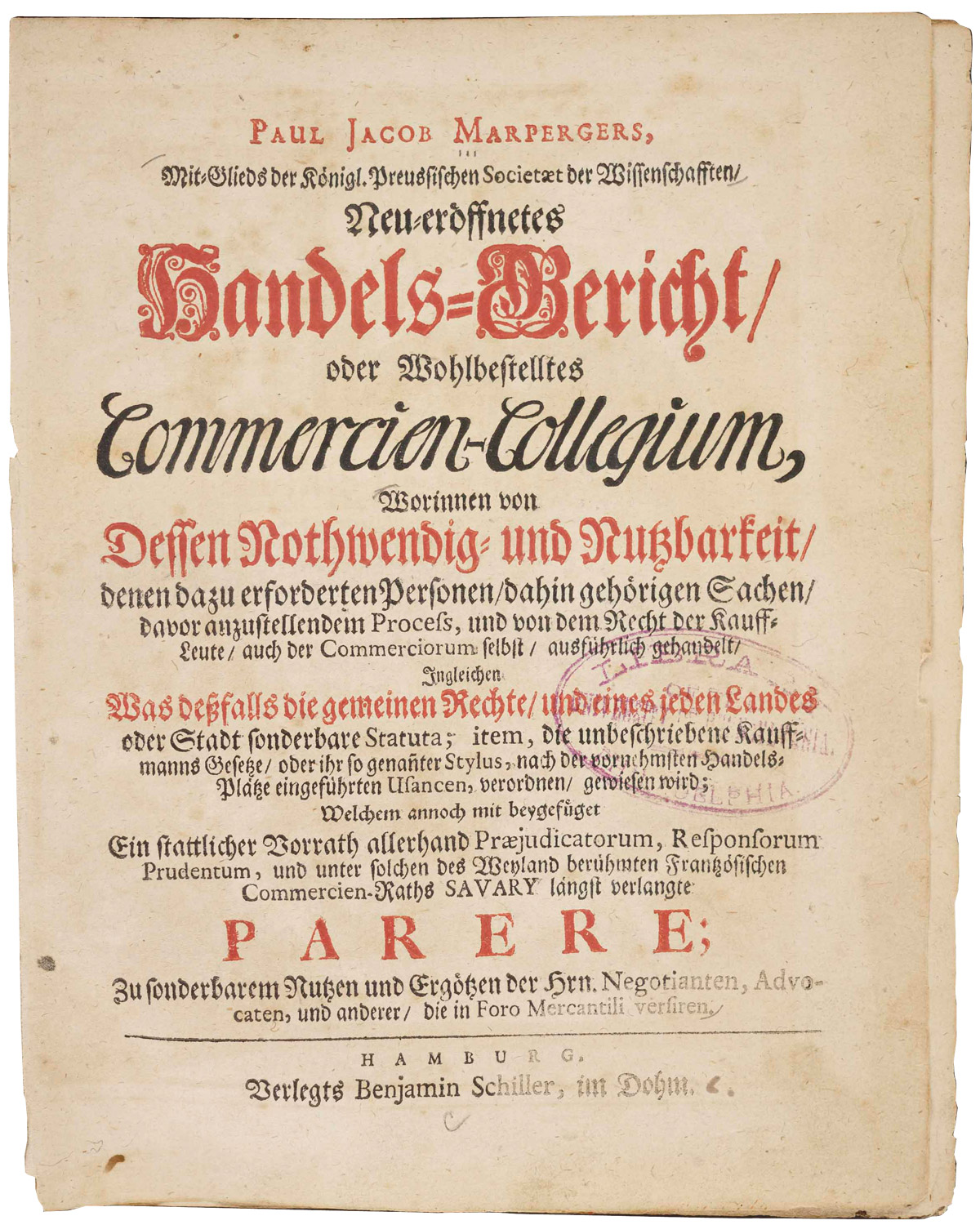

This is the front page of Paul Jacob Marperger's work on the usefulness and duties of the newly-founded commercial council in Prussia. Marperger (1656-1730) was the son of a German officer but took an apprenticeship with a French trading house. He became one of the first German writers on issues of mercantilism, cameralism, and commercial practices. In this and numerous other works he discussed the importance and the obligations of the mercantilist state. He examined the mechanisms of commerce, commercial courts, different commercial laws and regulations, bills of exchange and a wide array of similar topics. In 1708, he became a member of the Prussian Society of the Sciences and in 1724, he was appointed to the Royal Court and Commerce Council of Poland and the Electorate of Saxony.

The title page is accompanied by a copper engraving that depicts the members of the commercial council holding an open book with the inscription Fides et Veritas [Faith and Truth] across from a group of merchants who bring forward complaints and appeals to the council. In the background, a number of merchants are sitting around a table with different writing utensils, probably drawing a contract, while outside the window one recognizes the sea with incoming ships, a covered market building, an open market space, merchants, coaches, as well as barrels and packs of merchandize. A scroll on top of the picture names some of the most important places of commerce in Europe: Amsterdam, Bordeaux, Breslau, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig, Nuremberg, Lyon, and Venice. While Jewish merchants do not figure prominently in Marpergerb's work, they took a very active part in the commerce of early modern Europe and were regular visitors of fairs. Specific commercial courts became more and more a necessity with the growing volume of trade and the increase of complicated credit actions that were facilitated through bills of exchange. In Leipzig, which held one of the most important fairs, a commercial court was founded in 1682 because the municipal courts were overwhelmed with the amount and intricacy of the cases brought before it.

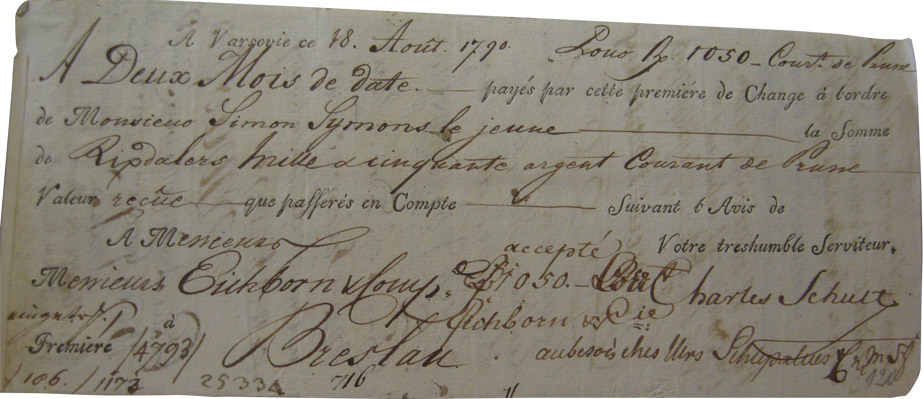

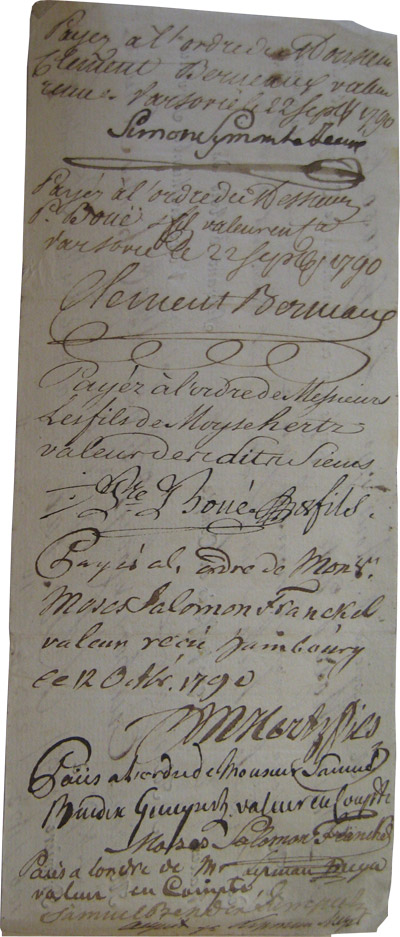

Though bills of exchange have existed since the Middle Ages, they became more suitable for long-distance trade and the provision of credit, which both were closely intertwined, in the early modern period with the general acceptance of the endorsement on the back of the bill. This allowed circulating a bill of exchange as currency which made bill transactions more flexible. This bill of exchange was issued in Warsaw in 1790 by a non-Jewish merchant to the Jewish banker Simon Symons from Amsterdam. It could be redeemed two months later from the Christian banking house Eichborn & Co. in Breslau.

On the back, one can see how it went through the hands of six different Christian and Jewish merchants and bankers and from Warsaw to Hamburg and Berlin before the bill was met in Breslau. However, the use of bills of exchange and especially their wide circulation had to be based on trust since everyone in the chain who paid (in cash or goods) had to rely not only on the previous endorser but on the original drawer or on every person involved in the chain of circulation. False bills of exchange were not a rarity and it was not uncommon that an original drawer had no credit with the payer. Thus, commercial courts that were competent to deal with complicated matters of bills and commerce were regarded as crucial by Marperger and others.

In Dispute: Commerce, Commercial Courts, and Bills of Exchange

This is the front page of Paul Jacob Marperger's work on the usefulness and duties of the newly-founded commercial council in Prussia. Marperger (1656-1730) was the son of a German officer but took an apprenticeship with a French trading house. He became one of the first German writers on issues of mercantilism, cameralism, and commercial practices. In this and numerous other works he discussed the importance and the obligations of the mercantilist state. He examined the mechanisms of commerce, commercial courts, different commercial laws and regulations, bills of exchange and a wide array of similar topics. In 1708, he became a member of the Prussian Society of the Sciences and in 1724, he was appointed to the Royal Court and Commerce Council of Poland and the Electorate of Saxony.

The title page is accompanied by a copper engraving that depicts the members of the commercial council holding an open book with the inscription Fides et Veritas [Faith and Truth] across from a group of merchants who bring forward complaints and appeals to the council. In the background, a number of merchants are sitting around a table with different writing utensils, probably drawing a contract, while outside the window one recognizes the sea with incoming ships, a covered market building, an open market space, merchants, coaches, as well as barrels and packs of merchandize. A scroll on top of the picture names some of the most important places of commerce in Europe: Amsterdam, Bordeaux, Breslau, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig, Nuremberg, Lyon, and Venice. While Jewish merchants do not figure prominently in Marpergerb's work, they took a very active part in the commerce of early modern Europe and were regular visitors of fairs. Specific commercial courts became more and more a necessity with the growing volume of trade and the increase of complicated credit actions that were facilitated through bills of exchange. In Leipzig, which held one of the most important fairs, a commercial court was founded in 1682 because the municipal courts were overwhelmed with the amount and intricacy of the cases brought before it.

Though bills of exchange have existed since the Middle Ages, they became more suitable for long-distance trade and the provision of credit, which both were closely intertwined, in the early modern period with the general acceptance of the endorsement on the back of the bill. This allowed circulating a bill of exchange as currency which made bill transactions more flexible. This bill of exchange was issued in Warsaw in 1790 by a non-Jewish merchant to the Jewish banker Simon Symons from Amsterdam. It could be redeemed two months later from the Christian banking house Eichborn & Co. in Breslau.

On the back, one can see how it went through the hands of six different Christian and Jewish merchants and bankers and from Warsaw to Hamburg and Berlin before the bill was met in Breslau. However, the use of bills of exchange and especially their wide circulation had to be based on trust since everyone in the chain who paid (in cash or goods) had to rely not only on the previous endorser but on the original drawer or on every person involved in the chain of circulation. False bills of exchange were not a rarity and it was not uncommon that an original drawer had no credit with the payer. Thus, commercial courts that were competent to deal with complicated matters of bills and commerce were regarded as crucial by Marperger and others.

In Dispute: Commerce, Commercial Courts, and Bills of Exchange

This is the front page of Paul Jacob Marperger's work on the usefulness and duties of the newly-founded commercial council in Prussia. Marperger (1656-1730) was the son of a German officer but took an apprenticeship with a French trading house. He became one of the first German writers on issues of mercantilism, cameralism, and commercial practices. In this and numerous other works he discussed the importance and the obligations of the mercantilist state. He examined the mechanisms of commerce, commercial courts, different commercial laws and regulations, bills of exchange and a wide array of similar topics. In 1708, he became a member of the Prussian Society of the Sciences and in 1724, he was appointed to the Royal Court and Commerce Council of Poland and the Electorate of Saxony.

The title page is accompanied by a copper engraving that depicts the members of the commercial council holding an open book with the inscription Fides et Veritas [Faith and Truth] across from a group of merchants who bring forward complaints and appeals to the council. In the background, a number of merchants are sitting around a table with different writing utensils, probably drawing a contract, while outside the window one recognizes the sea with incoming ships, a covered market building, an open market space, merchants, coaches, as well as barrels and packs of merchandize. A scroll on top of the picture names some of the most important places of commerce in Europe: Amsterdam, Bordeaux, Breslau, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig, Nuremberg, Lyon, and Venice. While Jewish merchants do not figure prominently in Marpergerb's work, they took a very active part in the commerce of early modern Europe and were regular visitors of fairs. Specific commercial courts became more and more a necessity with the growing volume of trade and the increase of complicated credit actions that were facilitated through bills of exchange. In Leipzig, which held one of the most important fairs, a commercial court was founded in 1682 because the municipal courts were overwhelmed with the amount and intricacy of the cases brought before it.

Though bills of exchange have existed since the Middle Ages, they became more suitable for long-distance trade and the provision of credit, which both were closely intertwined, in the early modern period with the general acceptance of the endorsement on the back of the bill. This allowed circulating a bill of exchange as currency which made bill transactions more flexible. This bill of exchange was issued in Warsaw in 1790 by a non-Jewish merchant to the Jewish banker Simon Symons from Amsterdam. It could be redeemed two months later from the Christian banking house Eichborn & Co. in Breslau.

On the back, one can see how it went through the hands of six different Christian and Jewish merchants and bankers and from Warsaw to Hamburg and Berlin before the bill was met in Breslau. However, the use of bills of exchange and especially their wide circulation had to be based on trust since everyone in the chain who paid (in cash or goods) had to rely not only on the previous endorser but on the original drawer or on every person involved in the chain of circulation. False bills of exchange were not a rarity and it was not uncommon that an original drawer had no credit with the payer. Thus, commercial courts that were competent to deal with complicated matters of bills and commerce were regarded as crucial by Marperger and others.

In Dispute: Commerce, Commercial Courts, and Bills of Exchange

This is the front page of Paul Jacob Marperger's work on the usefulness and duties of the newly-founded commercial council in Prussia. Marperger (1656-1730) was the son of a German officer but took an apprenticeship with a French trading house. He became one of the first German writers on issues of mercantilism, cameralism, and commercial practices. In this and numerous other works he discussed the importance and the obligations of the mercantilist state. He examined the mechanisms of commerce, commercial courts, different commercial laws and regulations, bills of exchange and a wide array of similar topics. In 1708, he became a member of the Prussian Society of the Sciences and in 1724, he was appointed to the Royal Court and Commerce Council of Poland and the Electorate of Saxony.

The title page is accompanied by a copper engraving that depicts the members of the commercial council holding an open book with the inscription Fides et Veritas [Faith and Truth] across from a group of merchants who bring forward complaints and appeals to the council. In the background, a number of merchants are sitting around a table with different writing utensils, probably drawing a contract, while outside the window one recognizes the sea with incoming ships, a covered market building, an open market space, merchants, coaches, as well as barrels and packs of merchandize. A scroll on top of the picture names some of the most important places of commerce in Europe: Amsterdam, Bordeaux, Breslau, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig, Nuremberg, Lyon, and Venice. While Jewish merchants do not figure prominently in Marpergerb's work, they took a very active part in the commerce of early modern Europe and were regular visitors of fairs. Specific commercial courts became more and more a necessity with the growing volume of trade and the increase of complicated credit actions that were facilitated through bills of exchange. In Leipzig, which held one of the most important fairs, a commercial court was founded in 1682 because the municipal courts were overwhelmed with the amount and intricacy of the cases brought before it.

Though bills of exchange have existed since the Middle Ages, they became more suitable for long-distance trade and the provision of credit, which both were closely intertwined, in the early modern period with the general acceptance of the endorsement on the back of the bill. This allowed circulating a bill of exchange as currency which made bill transactions more flexible. This bill of exchange was issued in Warsaw in 1790 by a non-Jewish merchant to the Jewish banker Simon Symons from Amsterdam. It could be redeemed two months later from the Christian banking house Eichborn & Co. in Breslau.

On the back, one can see how it went through the hands of six different Christian and Jewish merchants and bankers and from Warsaw to Hamburg and Berlin before the bill was met in Breslau. However, the use of bills of exchange and especially their wide circulation had to be based on trust since everyone in the chain who paid (in cash or goods) had to rely not only on the previous endorser but on the original drawer or on every person involved in the chain of circulation. False bills of exchange were not a rarity and it was not uncommon that an original drawer had no credit with the payer. Thus, commercial courts that were competent to deal with complicated matters of bills and commerce were regarded as crucial by Marperger and others.

Sephardic Merchant Trade

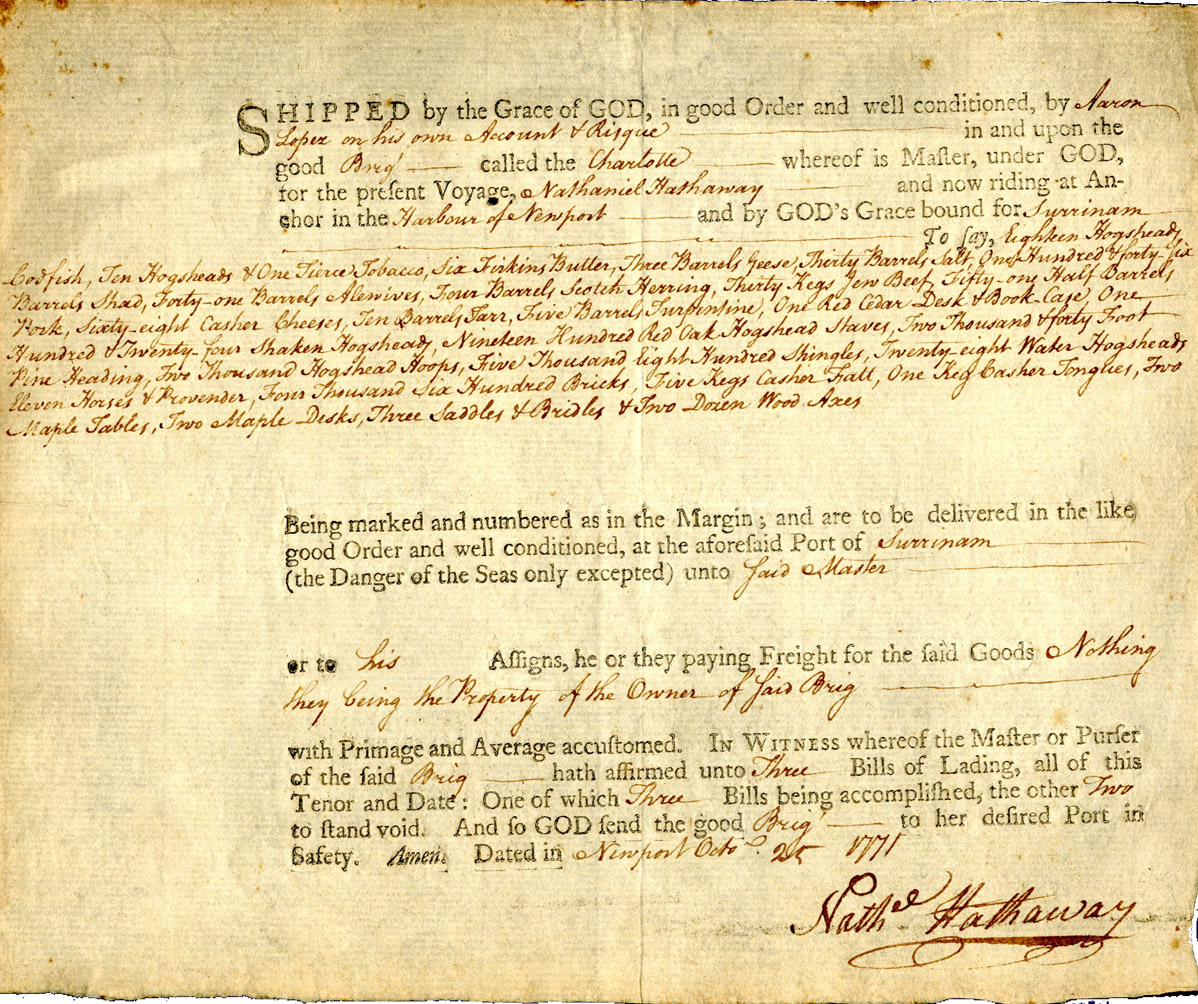

This bill of lading, drawn up in 1771, describes the cargo shipped from Newport to Surinam by Aaron Lopez, a Sephardi merchant who lived as a New Christian in Portugal until 1752 when he fled Lisbon to join his brother in Newport. During the following decade, in the context of the French and Indian war, Lopez expanded the scope of his mercantile activities to Western Europe, the Caribbean, Newfoundland, Africa, and when this document was drawn up he had become one of Newport's leading merchants.

Several features of early modern commerce may be emphasized using this document, which belongs to the Library at the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, but which is one of many preserved in Aaron Lopez's papers, seized after his premature death (1782) in order to assess his indebtedness. The most striking feature is the variety of commodities composing this cargo. Even if Lopez is known for his contribution to the trade in spermaceti (the head matter of the sperm whale used in the manufacturing of candles), which does not appear in this cargo, this document epitomizes the nature of early modern trade, generally not specialized but, rather, organized along routes, the merchants trading in whatever wares are available or in demand and likely to bring about a profit: here together with naval stores, construction materials (bricks), we have items related to cooperage, (hogsheads, i.e., barrel staves or hoops, dismantled barrels,. . .), horses, pieces of furniture, tobacco, as well as a variety of foods intended for different groups of consumers: pork, butter, herring, but also kosher foods, "Jew beef," "Casher Fatt," "Casher Tongues." Thus, together with the standard routes and products of colonial trade, the sub-species of kosher trade features here prominently.

Aaron Lopez was providing similar wares to other Caribbean communities, namely Jamaica and Curaçao. This bill mentions that Aaron Lopez owns the brig - therefore no freight is to be paid - and not only the merchandise. Around 1772, Aaron Lopez owned about twenty ships. Another essential actor of this maritime trade appears here with the figure of the Captain: much of the enterprise rested on the Captain's skills and a trusting relationship between him and the merchant was essential to a successful venture, for which the captain was often rewarded with a commission on top of his salary.

The goods mentioned in this cargo are sent to Surinam, a Dutch possession, plausibly to Jewish and non-Jewish correspondents. This consignment is but one aspect of the links between Jewish communities in colonial America: a few years earlier, for instance, the Surinam Portuguese community had agreed to make a substantial donation to help the congregation Yeshuat Israel of Newport complete the building of its synagogue. Merchant networks, though implicit in this document, do not feature directly in it: Lopez's partners, in Newport, London or the Caribbean comprised Jews and non-Jews, Askenazi and Sephardi merchants. Other essential aspects of Aaron Lopez's mercantile activities do not appear here, such as his involvement in the slave trade, but should be recalled in order to understand the scope and nature of his mercantile activities.

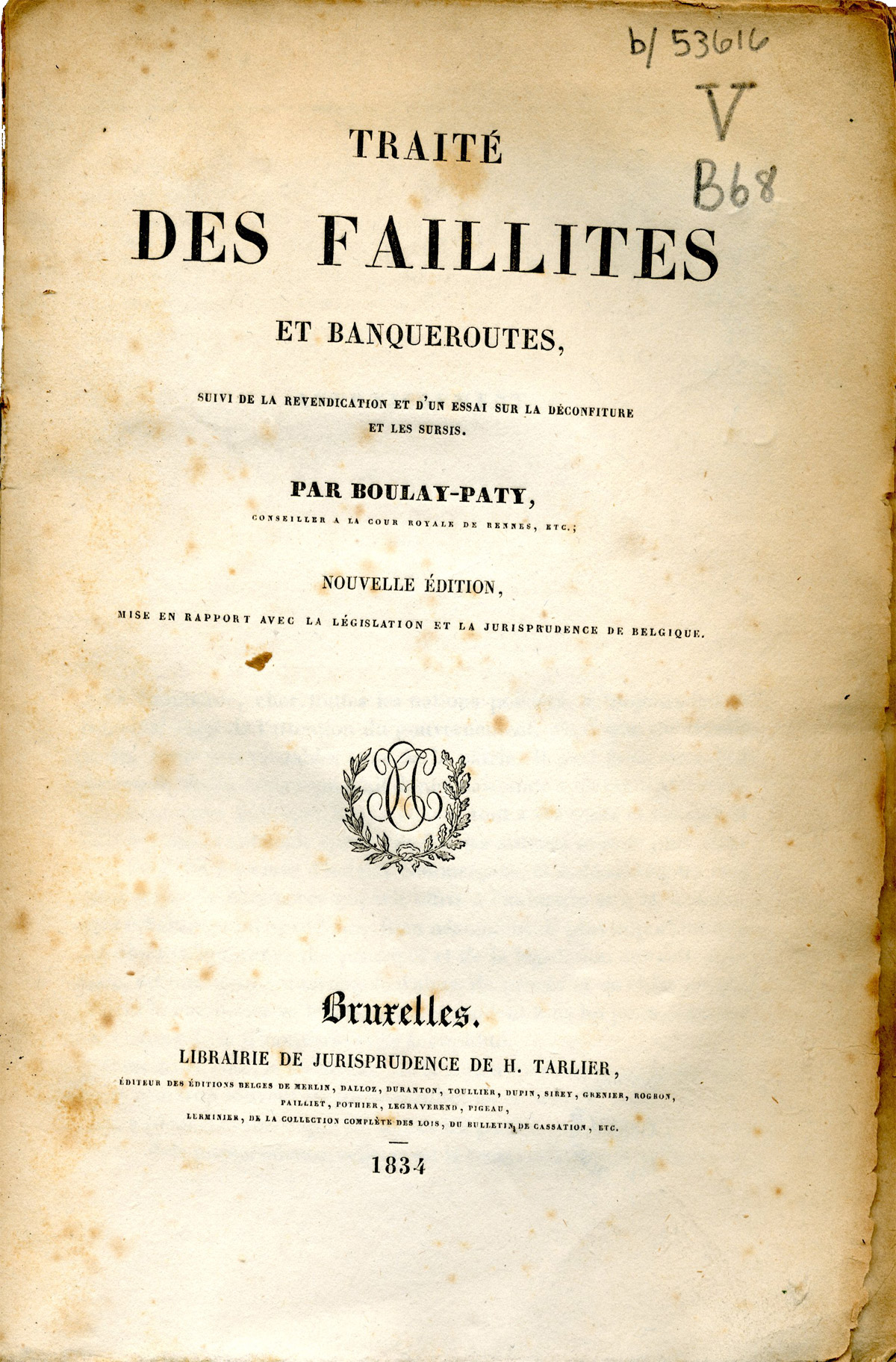

Going for Broke: Traité des Faillites et Banqueroutes

Traité des Faillites et Banqueroutes, written in the early 19th century, is one of the first attempts to collect and codify bankruptcy laws both in France and through Europe. Until then, bankruptcy law had been a hodgepodge of local, regional, national, and common law. This effort was an implicit recognition of what had been clear since time immemorial - merchants could and did renege on their debts, leading themselves and their entire business networks into insolvency. In short, networks could and did fail.

Sephardic networks were as prone to disintegration as any other. A close look at the archival documentation of the Amsterdam Sephardic community paints a picture of fractiousness, dissent, religious unrest, and civil lawsuits. This reality challenges the conventional wisdom of the efficiency of Jewish trade networks based on family, kinship, and shared ethno-religious background. In fact, Sephardic traders in 17th century Amsterdam often brought each other to ruin, either through bad luck, ineptitude, or malfeasance. Their tightly-woven networks only exacerbated the domino effect if one merchant failed. Sephardic merchants were as likely as any other to declare bankruptcy in civil court, and depend on the law, such as it was, to decide their fate.

Ludwig Börne and the predicament of Jewish class relations

Ludwig Börne was born - as Juda Löw Baruch - in 1786 into a wealthy banking family in the Frankfurt Ghetto. In 1811, taking advantage of the Napoleonic emancipatory legislation, he took a position in the administration of Frankfurt's police records. In 1815, when these laws was revoked, Börne lost his job. For the rest of his life, despite his conversion to Protestantism in 1819, he made his living as an outsider: a freelance writer, journalist and political radical. He rushed to Paris when revolution broke out there in July 1830, and lived there almost continually, in effective exile, until his death in 1837.

Börne decisively rejected his religious upbringing, and his writings include plenty of hostile comments about Jews, and particularly about Jewish commerce. However, far from being a 'self-hating Jew,' Börne was keenly aware of the Jews' political vulnerability. He understood this, however, within a wider context of class relations between the ruling elite and the oppressed masses, between whom the Jews, because of their intermediary economic role, were precariously squeezed, serving elites as a protective shield. Börne's political thought was characterized by a striking clarity concerning power relations in society, an engaged realism, a commitment to economic and political justice, and a loosely messianic sense of impending transformation. In all of these aspects his ideas were profoundly shaped by his Jewish background.

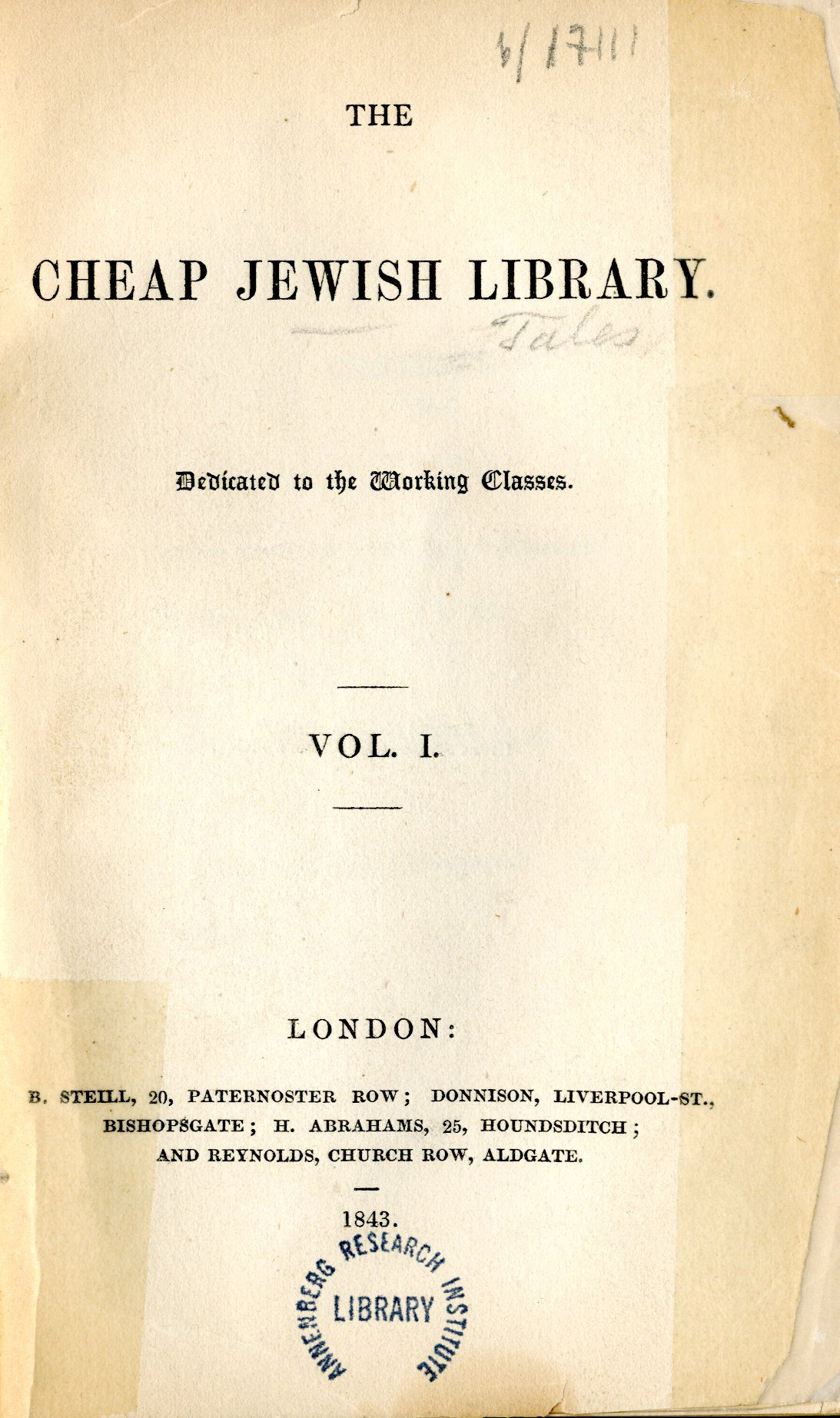

The Cheap Jewish Library

In the middle of the nineteenth century, publishers in the United States and England began to court a mass Jewish market, producing literature - newspapers, tracts, catechisms, novels, and Bibles - for distribution cheaply and in large quantities. This trend was partly a result of the falling costs of printing. Yet its initial driving impulse came from missionary publishers rather than Jewish sources. Christian Evangelicals were among the first to grasp the implications of mass publishing, skillfully utilizing the printing press to communicate with their followers and win new converts.

The scale and persistence of mission efforts to supply Jews in America and England with their literature galvanized a Jewish response. While this response was undoubtedly defensive, it also reflected a new awareness of pent-up demand among Jews for books, tracts, pamphlets, printed sermons, and Bibles.

The Cheap Jewish Library - the name echoed the immensely popular evangelical Cheap Repository Tracts - was started and subsidized anonymously by Charlotte Montefiore and her sister Louisa de Rothschild, daughters of the aristocratic Jewish cousinhood, in London in 1841. (David Aaron de Sola, the hazan at Bevis Marks handled the practicalities of publication.) Single-page tracts were sold for a penny - tantamount to giving them away - with the intention of reaching the "humbler classes" to provide "instruction by means of interesting tales."

The cheap tracts were intended to rival the flood of moralistic material that gushed from the presses of the interdenominational Religious Tract Society and the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. These and other publishing houses produced millions of tracts annually, saturating the reading public with a ceaseless tide of uplifting tales and exhortations that conveyed lessons in Christian faith and virtue. While Jewish writers had produced plenty of polemical anti-missionary works before the 1840s, the mass produce pamphlets produced under the Cheap Jewish Library imprint contained a more subtle counter conversionist agenda.

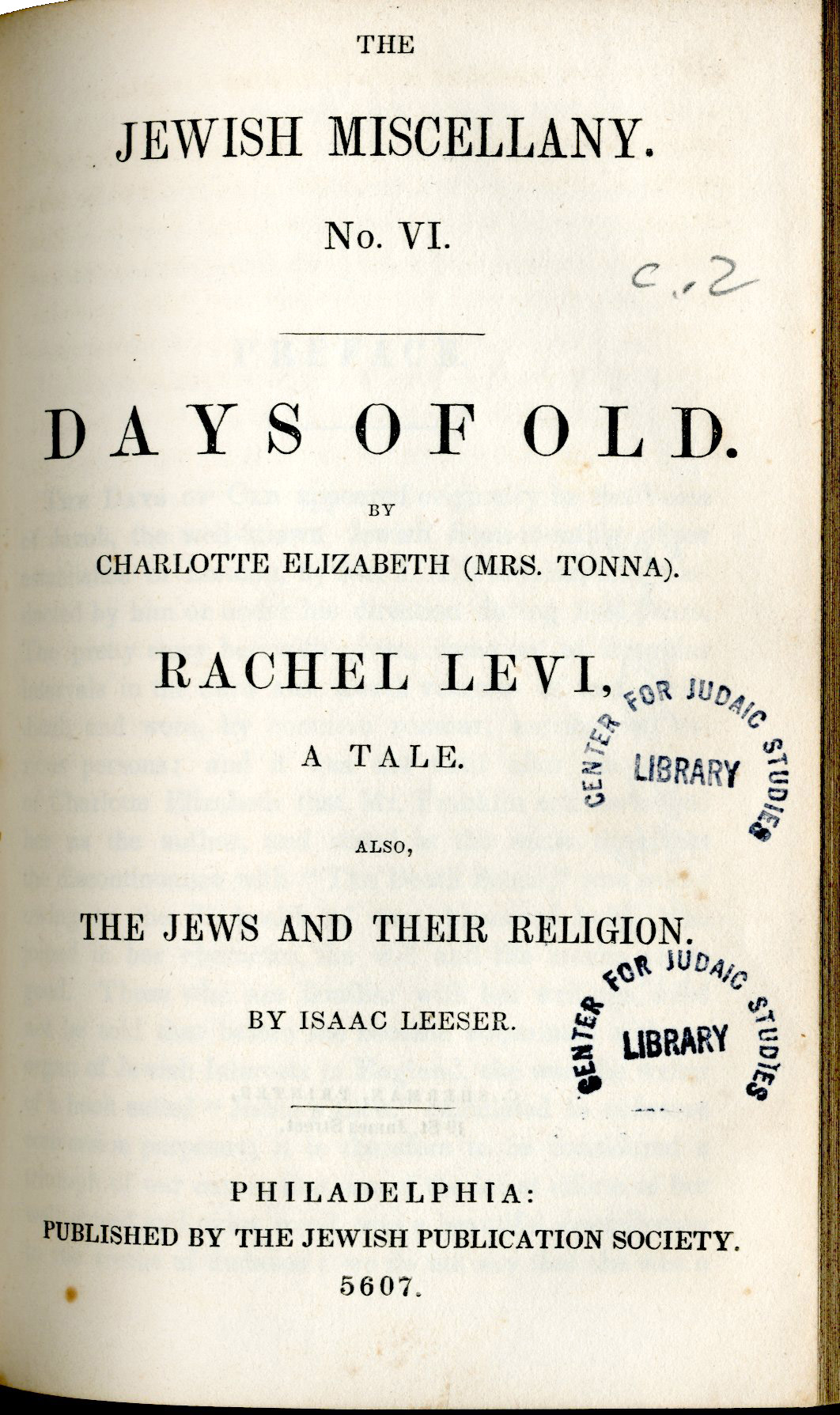

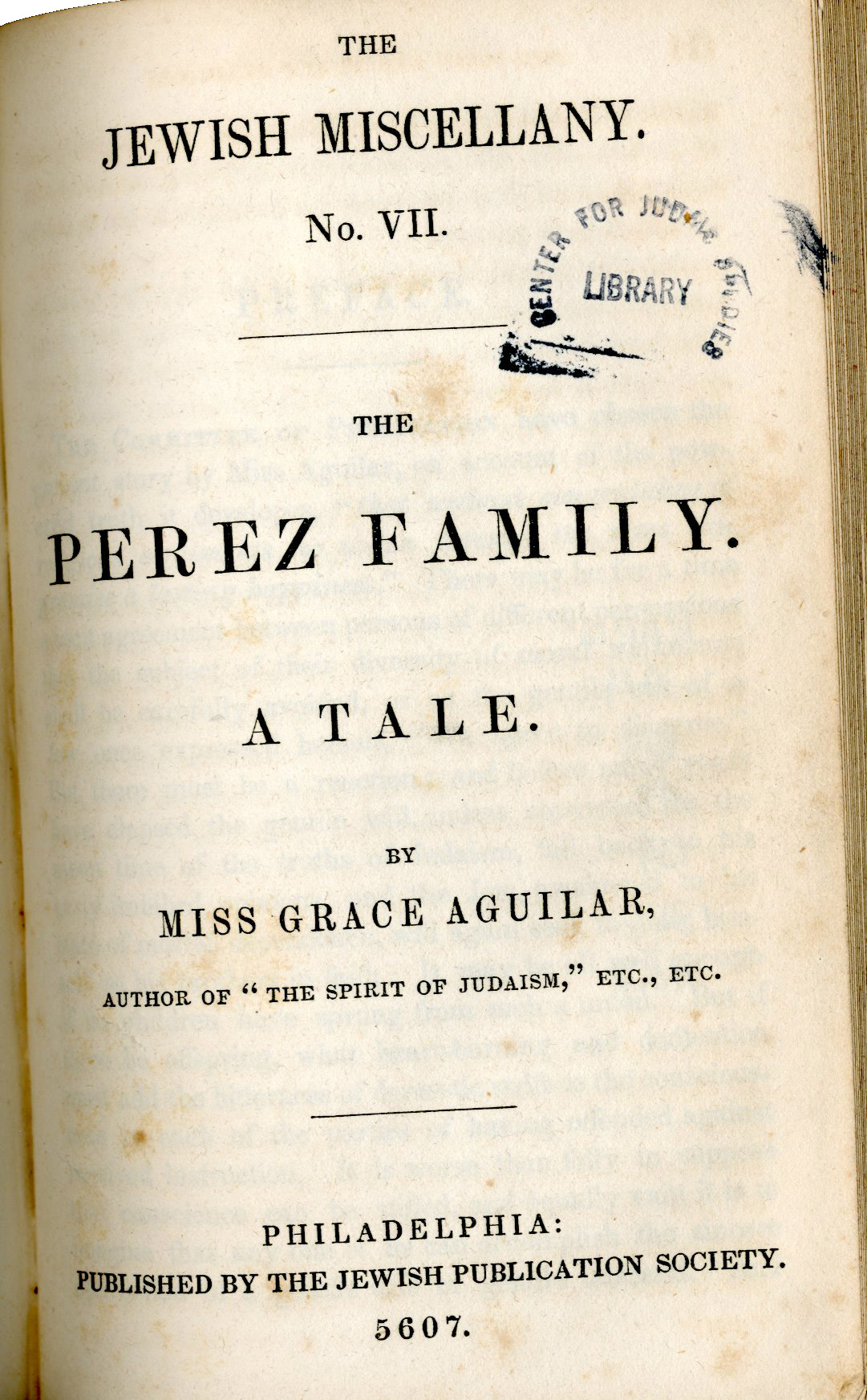

Like their Christian counterparts, the tracts tended towards saccharine stories, often barely concealing a core of "doctrinal information," Biblical and Jewish history. The tales were written by a roster of writers that included Grace Aguilar. Her serialized Perez Family, for example, depicted the evil consequences of irreligion and intermarriage. The patrician project also imparted "practical lessons for the everyday life": thinly disguised lectures on hygiene, decorum and comportment. The Cheap Jewish Library proved far more palatable on both sides of the Atlantic than some of the rival series produced under Jewish auspices. Isaac Leeser was an early and enthusiastic supporter of the series. His Jewish Publication Society, founded in Philadelphia in 1845, reprinted tracts from the Cheap Jewish Library under the Jewish Miscellany imprint.

The Cheap Jewish Library