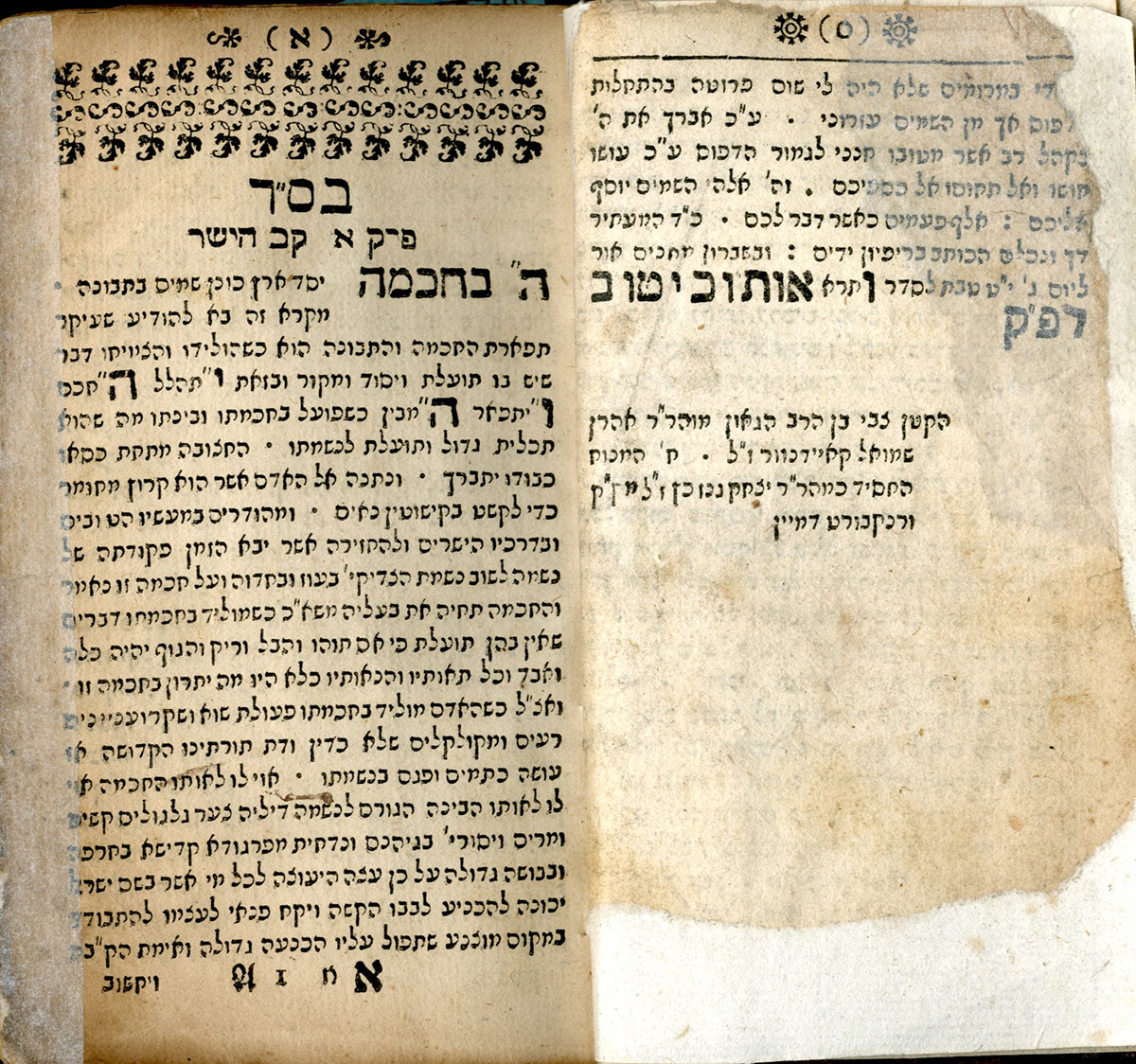

These pages are excerpted from the first edition (Frankfurt, 1705) of Kav ha-yashar ("A Just Measure"), by Zvi Hirsch Koidanover (1655-1712). (Image, left, top, shows the author' introduction and the first page.) This enormously popular demonologically-charged mystical ethical book was reprinted dozens upon dozens of times in Hebrew, produced in a bilingual Hebrew and Yiddish version by the author, and eventually translated into Ladino. Many of its admonitions and Zoharic excerpts appear aimed at traveling merchants, warning of the ethical pitfalls they might encounter on their journeys. The small dimensions of the book would seem to confirm this authorial intent. Koidanover was born in Vilna and raised in Kurów (near Lublin). He moved to Nikolsburg (Moravia) after 1655 and then settled in Frankfurt am Main in 1667. He later returned to Vilna, where he prospered but was imprisoned. He returned permanently to Frankfurt in 1696. His observations thus reflect the inner life of Jews in the Polish, Czech, and German lands.

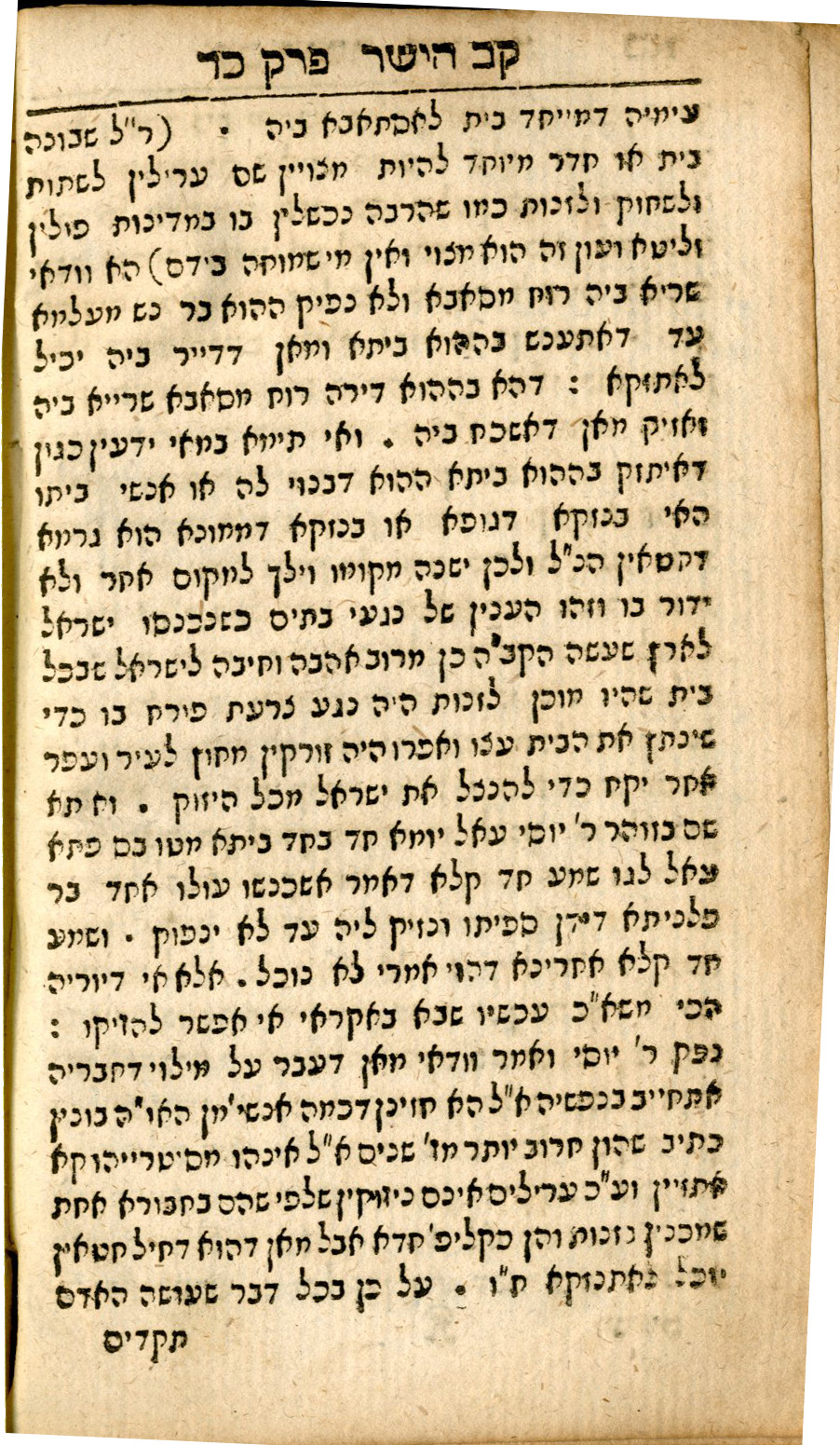

The pages reproduced here reflect the fascinating relationship between Jews and alcohol. By the end of the eighteenth century about 80 percent of rural Jews in Poland-Lithuania were involved in the sale and production of liquor. According to available data, Jews comprised 94 percent of urban and at least 78.7 percent of rural tavern keepers among seven towns and fifty-one villages in Bielsk County (Podlaskie District) during this period. A centerpiece of the reform initiatives of the Prussian, Russian, and Austrian monarchs who annexed the Polish lands during this period was the elimination of the rural Jewish liquor trade, which they attempted by means of escalating concession fees and outright expulsions. Surprisingly, few rabbinic or Hasidic leaders protested these draconian measures. It appears they themselves were uncomfortable with the tavern keeping profession. An excerpt from Kav ha-yashar (see images, left, middle) illustrates this ambivalence:

When one builds a house or designates a special room in one's house for the uncircumcised to come and drink, party, and fornicate, a common sin which many have committed in Poland and Lithuania, and which no one prohibits: In such a case the spirit of defilement will certainly settle upon the house and the one who built it will not leave this world until he is punished through that very house.

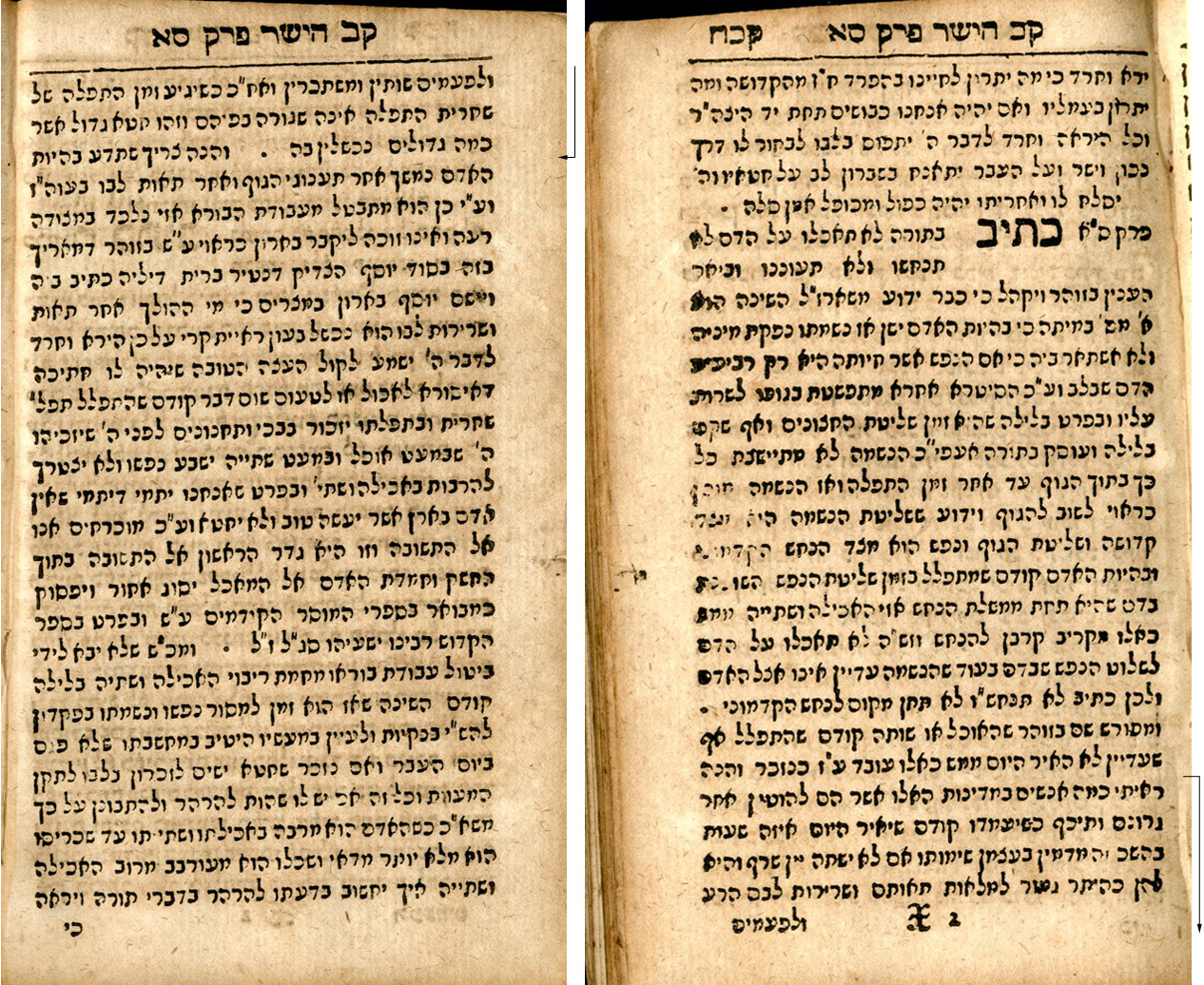

Why was the Polish nobility so inclined to lease its taverns and distilleries to Jews in the first place? Among the several explanations supplied by historians is the notion of Jewish sobriety: Jewish tavern keepers, in contrast to their Christian counterparts, tended not to drink up their profits. The following excerpt from Kav ha-yashar (see image, left, bottom) gives pause to such assumptions:

I have noticed that many people in this region are so enslaved to their appetites that immediately upon awakening, hours before dawn, they believe they will die if they do not drink liquor. And they think that it is perfectly permissible to indulge their lusts and stubborn hearts. And sometimes they drink to the point of intoxication. And afterwards, when the time of morning prayer arrives, their prayer is not fluent. And this is a terrible sin, which many luminaries have committed.

Nevertheless, we cannot conclude that alcoholism was a widespread problem in Jewish society. Such admonitions occur infrequently in ethical literature; while Slavic folk sayings reflect a widespread perception of Jewish sobriety during this period. There may still be something to the hypothesis!