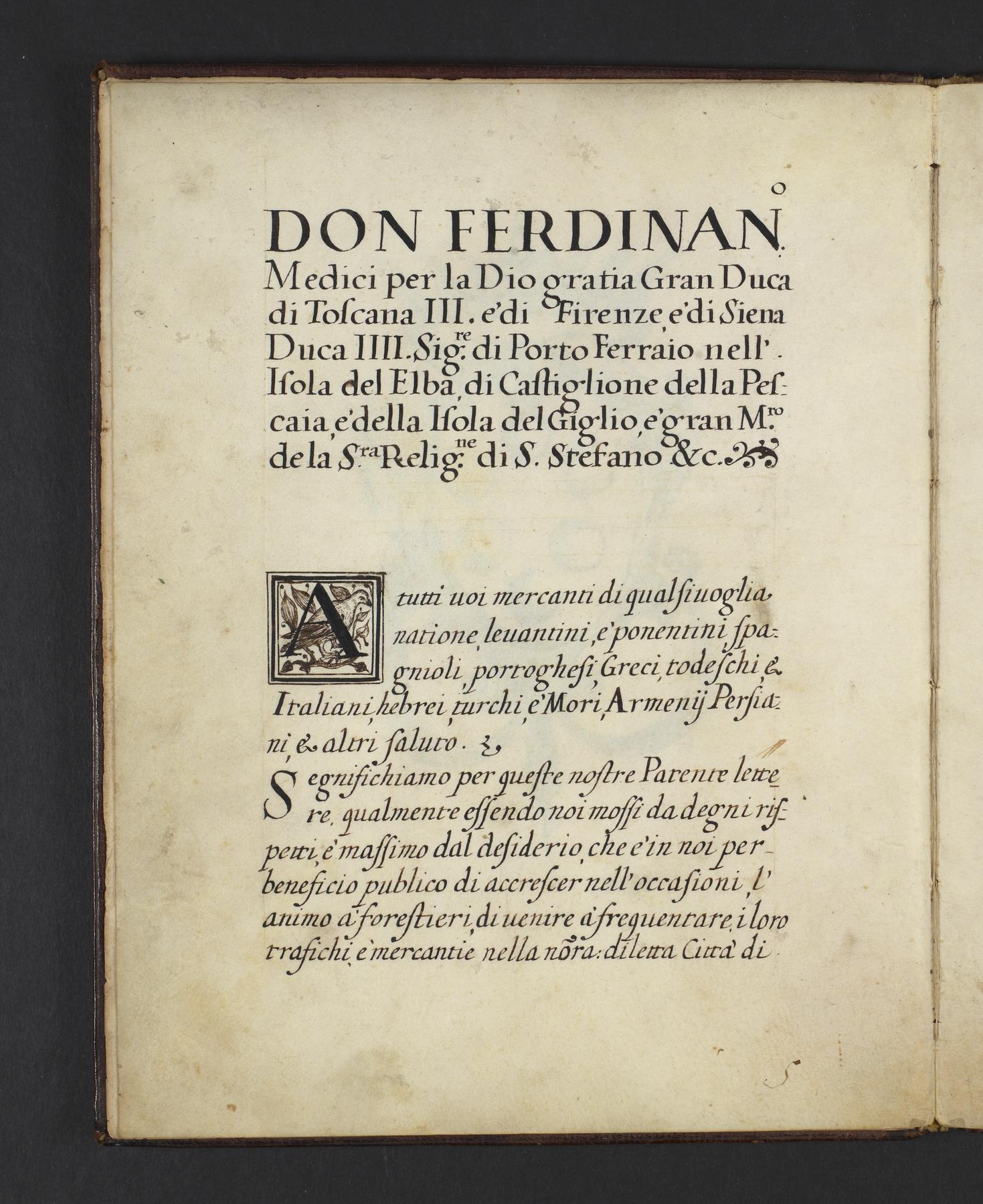

The port city of Livorno on the Tuscan coast was the home of arguably the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in Italy during the seventeenth century. Established by a special charter, the so-called Livornina, in 1593 (see image at left), the community was organized as a merchant "company." Subsidized by an enormous government loan, this corporation had special customs and tax privileges, its own recognized courts, and the right to admit (or refuse entry) to whomever it wished. The Medici rulers saw Jewish Sephardic merchants as a powerful force in Mediterranean trade and expected them to give Tuscany improved commercial access to the Ottoman Levant, Muslim North Africa, and (through converso relatives and contacts) the commercial network that radiated out from Spain and Portugal to encompass the entire globe.

Livorno was then little more than a fishing village, filled with sailors, soldiers, thieves and prostitutes, and surrounded by malarial marshes. The Medici were investing huge sums in the town and its port facilities because the older port at Pisa, a few miles up the coast, had silted up and become unusable for sea-going vessels. The Livornina charter (and the letters sent out to advertise it) clearly assume that the wealthy merchants would live in Pisa and use Livorno only as a shipping point. To everyone's surprise, however, it was Livorno that grew rapidly, and the Jewish community there soon outstripped its "mother colony" demanding jurisdictional and economic independence. While the growth of Livorno's Jewry was undoubtedly motivated by merchants' desire to live conveniently near the harbor, it seems that the younger community was initiated by quite a different group of settlers..

From the start it was clear that not all Jews were Sephardim (that is, of Iberian origin), nor were they all merchants. Italian Jewry of the era included many whose families had lived on the Peninsula for centuries, as well as thousands of recent immigrants from all over northern and western Europe. In many of the Italian states, government policy was becoming more restrictive towards Jews: outright expulsions or at least ghettoizations, were forcing Jews to move from place to place seeking haven and economic opportunity. Inevitably, some of these Jews appealed to the massari (communal stewards) in Pisa for admission, but the latter were unwilling to admit "undesirables" - that is, those likely to tarnish the image of Jews as wealthy and powerful merchants. Refused entry into the community of Pisa, some of these Jews appealed directly to the Medici for individual admission into Livorno.

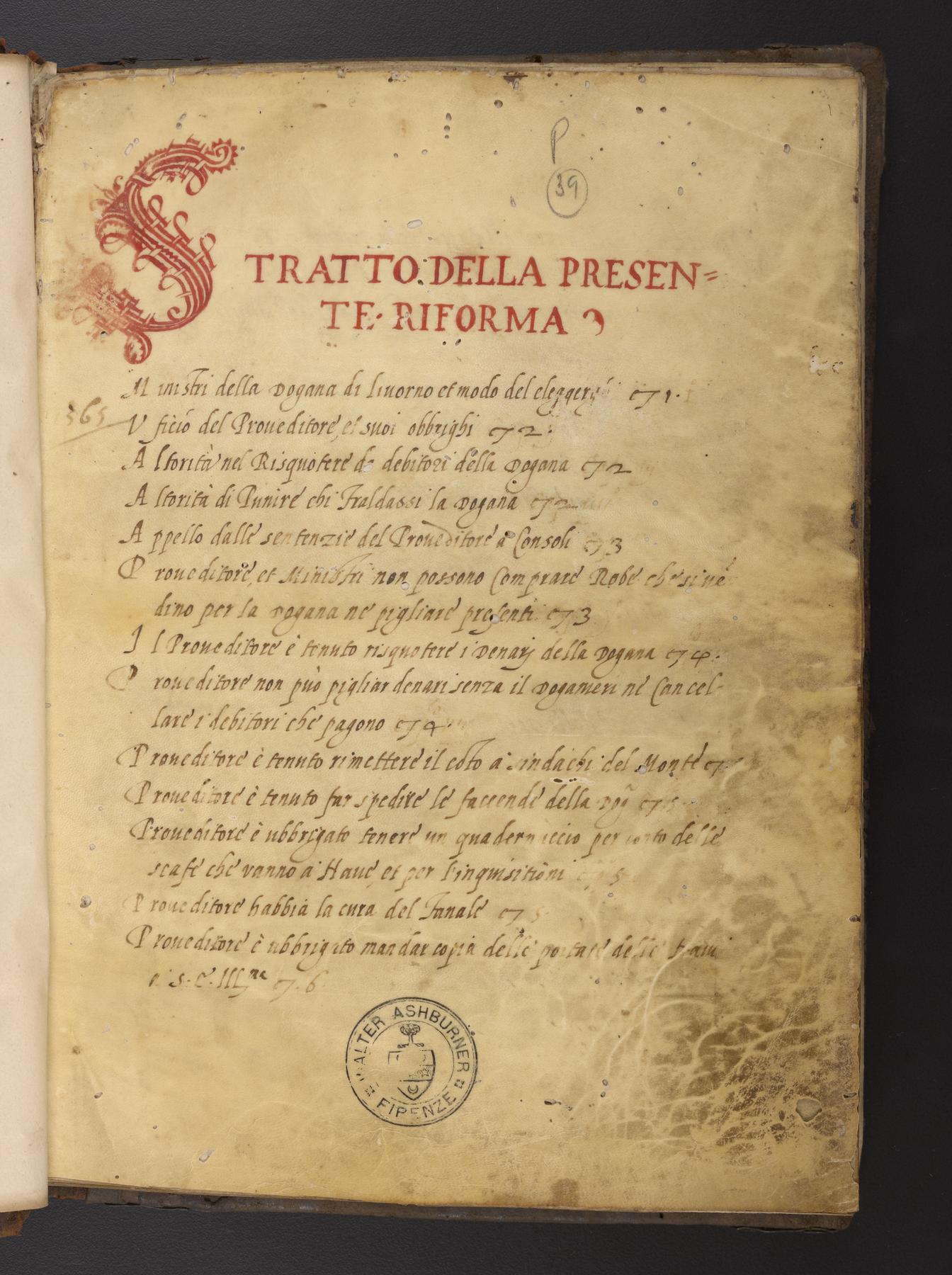

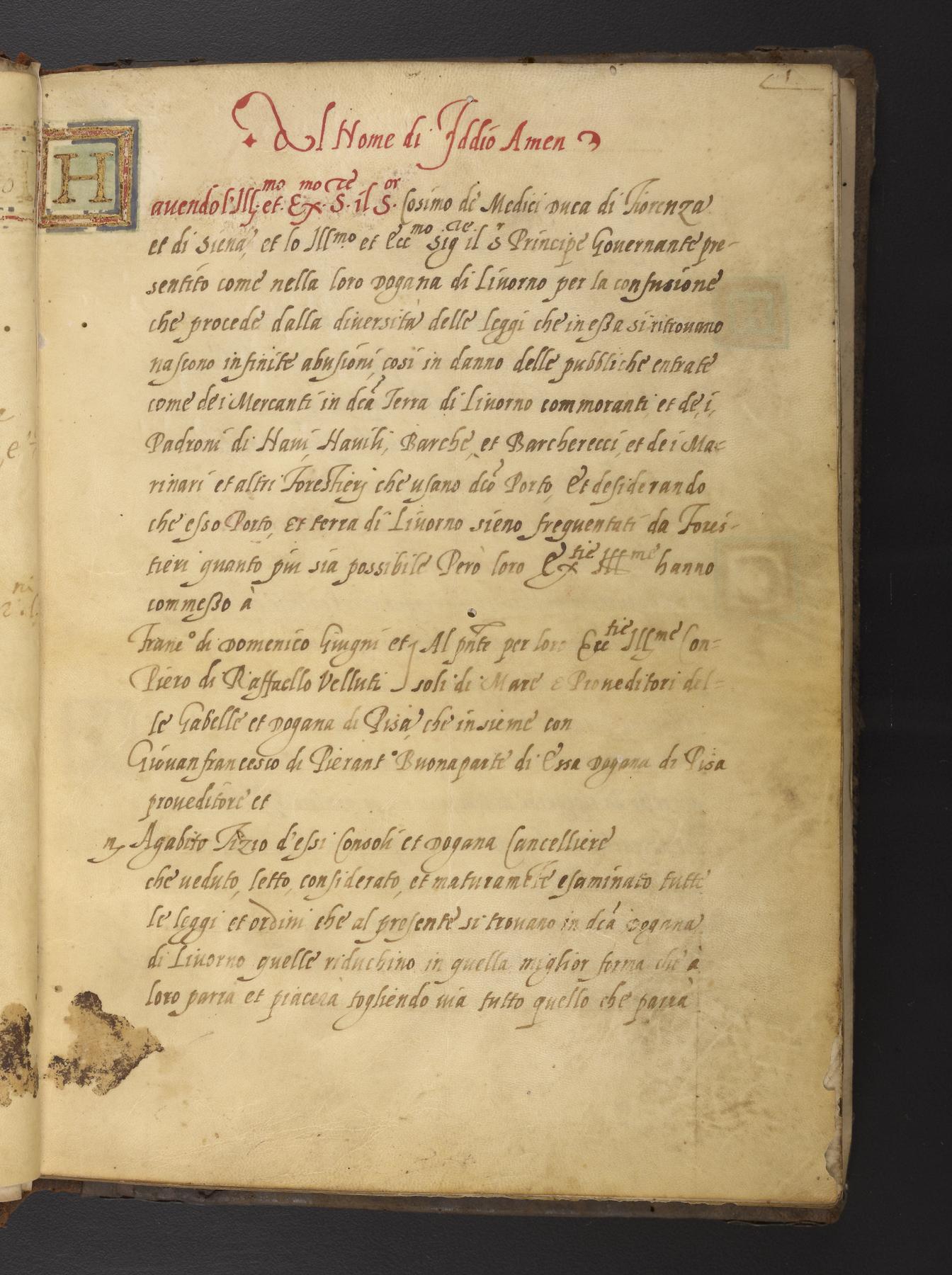

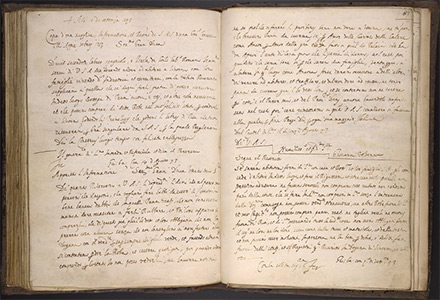

Displayed here are the title page, first page with benediction, and pages 82v-83r of a vellum manuscript, volume 1 of Codex 266, in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania. This volume was intended as the official reference copy of the Statuti della Dogana, the regulations of the customs house at Livorno, reformed in 1565. Blank pages were left at the end so that any important new ruling could be added.

One such ruling was issue in September of 1593 in answer to the petition by David Sacerdote, a Spanish Jew, and Isache de Goilo, a Jew from Rome, for permission to settle in Livorno with their families, to open a new- and used-clothing shop in the town, and to travel around the Medici state buying up used goods that they could sell in their shop. Asked for his opinion, the governor of Livorno responded positively, both as to the usefulness of the shop and as to the desirability of another two families coming to settle in the town, especially since they might attract others. He did have some worries, however. The shop might become an outlet for stolen property and so the Jews would have to agree to present any used item to the customs officials before putting it on sale. The trade in used items must not be used to cover a money-lending operation. The shop should not be allowed to trade in woolen cloths since that would compete with the recently licensed woolens manufacture in the city. Grand Duke Ferdinando agreed with the governor, licensing the shop under the general terms described (though restricting used clothing purchases to the area immediately around Pisa and Livorno), and freeing the partners and their wives from the obligation to wear the Jewish badge, from customs duties and taxes, and from prosecution for past debts incurred elsewhere. Thus the petitioners were granted almost all of the privileges of the Pisan community even though they were not part of it and had to be registered individually in Livorno.

Historians are often hesitant to describe the Jewish "rigattieri" and "straccieri" - the rag dealers and second-hand shopkeepers who were so much a feature of the Jewish economy in past centuries. By euphemistically and narrowly referring only to the wealthier "bankers," historians paint a picture of elegant financiers who are often also the cultural elite of their community. But Jewish "banks" were for the most part indistinguishable from what we now call pawnshops, serving, then as now, the marginal elements of society. This was a profitable, if risky and not particularly esteemed, profession, but it was one of the few available to Jews of sixteenth century Italy. It was the kind of activity that attracted Jews to the port of Livorno where a transient and often disreputable population often needed quick cash without too many questions asked. We can easily understand why wealthier Jewish merchants did not want to be associated with pawnbrokers and rag dealers. But government officials understood the economic need for such services, and in the frontier conditions of Livorno any settler, even a Jew, was to be valued. It was from such aggressive businessmen that the Jewish community of Livorno was to grow.