Sister Carrie

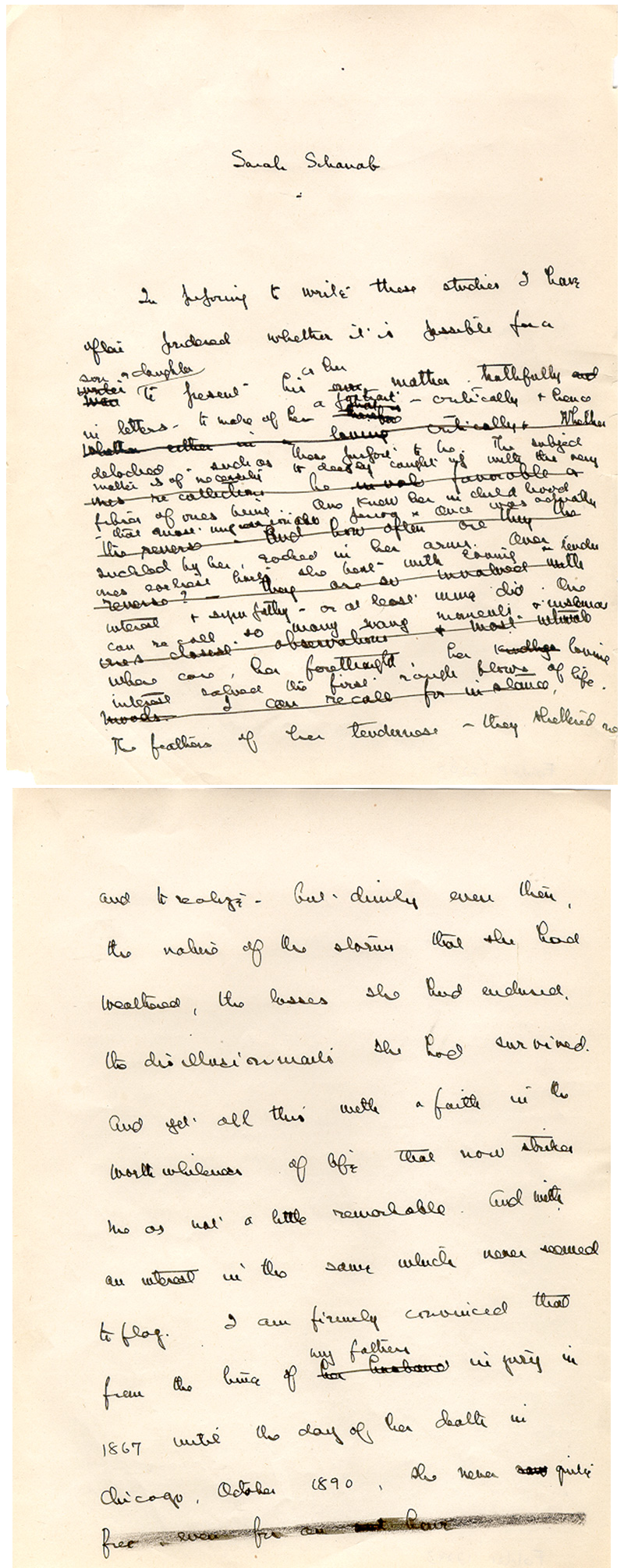

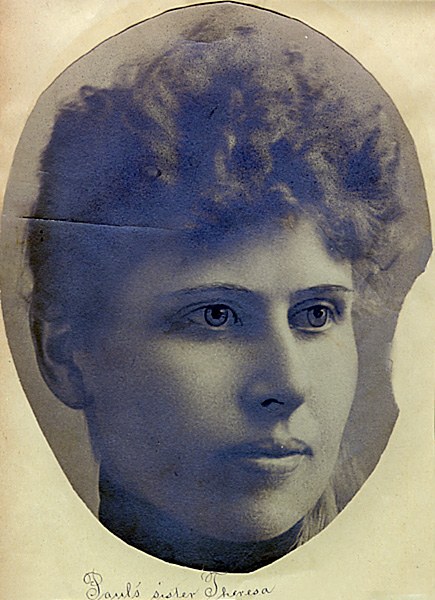

Sister Emma

Sister Emma

Sister Emma

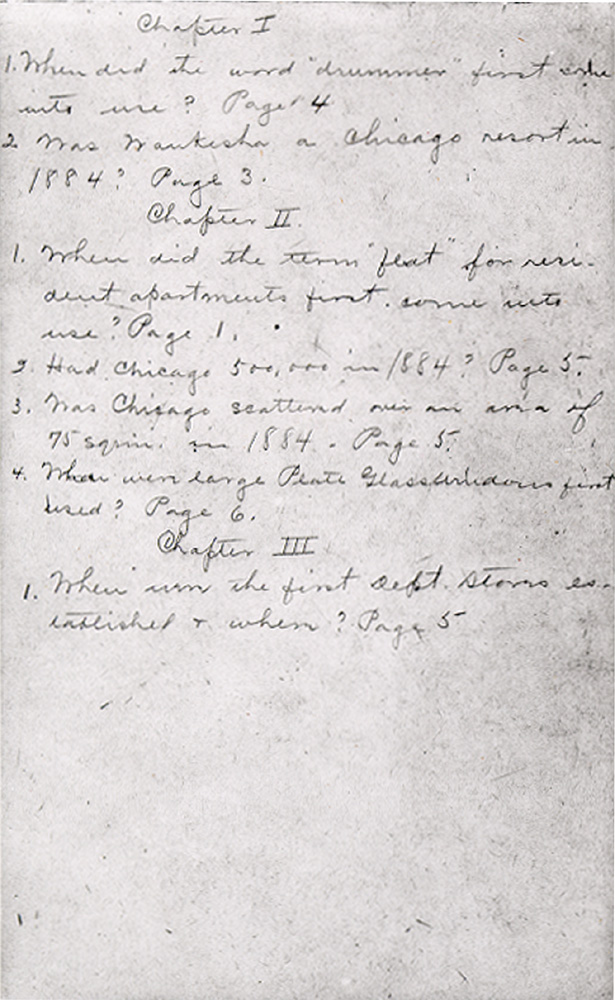

Dreiser's Apprenticeship

Dreiser's Apprenticeship

Dreiser's Apprenticeship

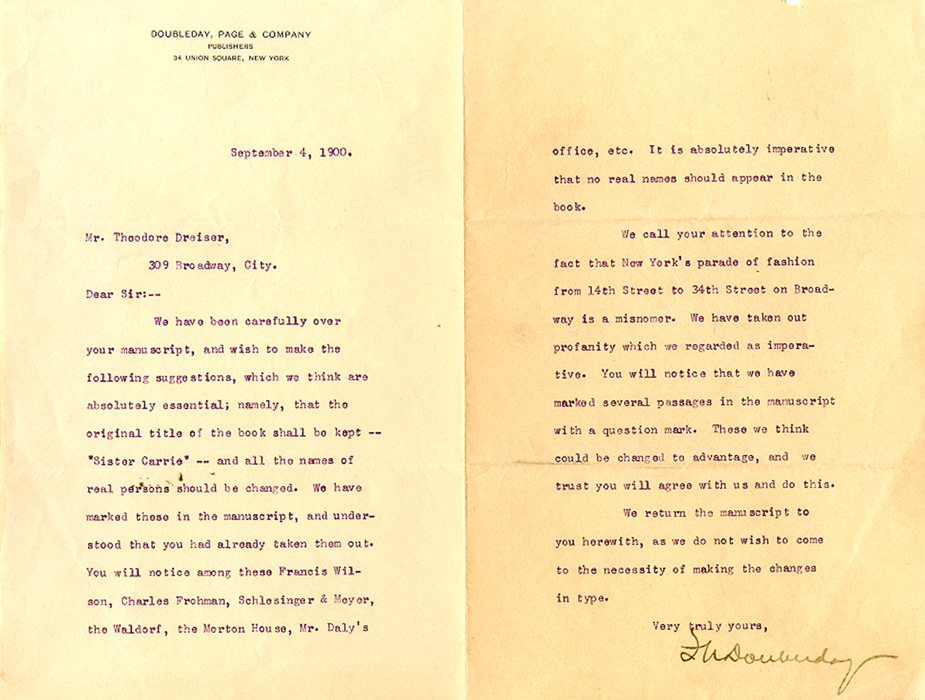

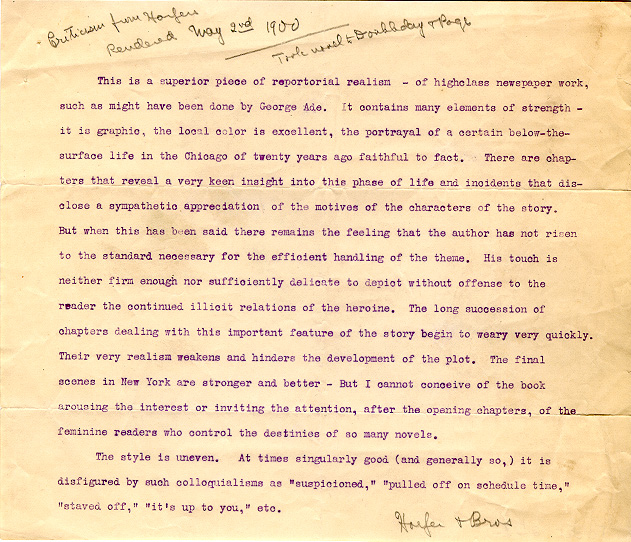

Sister Carrie in Search of a Publisher

Sister Carrie in Search of a Publisher

Sister Carrie in Search of a Publisher

Too Many Cooks?

Too Many Cooks?

Too Many Cooks?

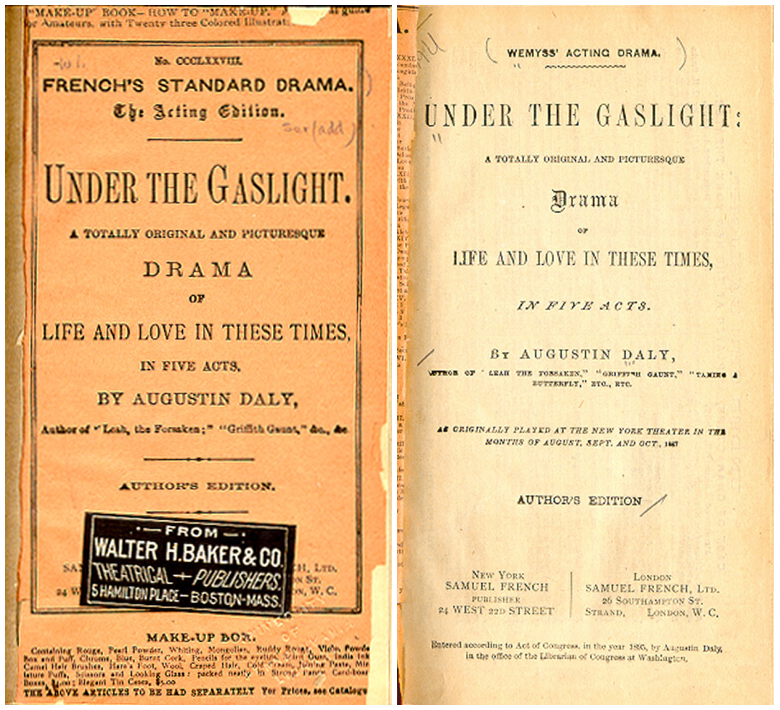

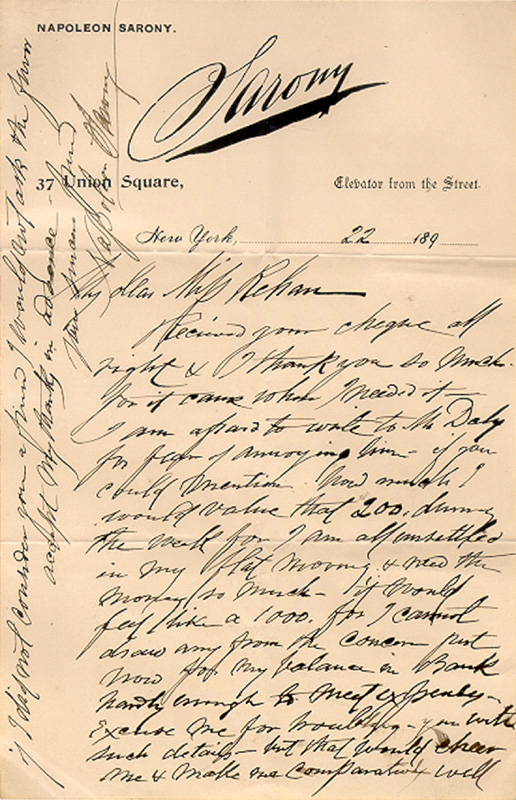

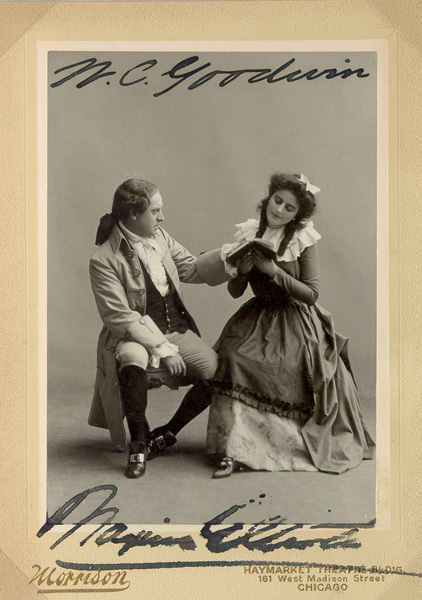

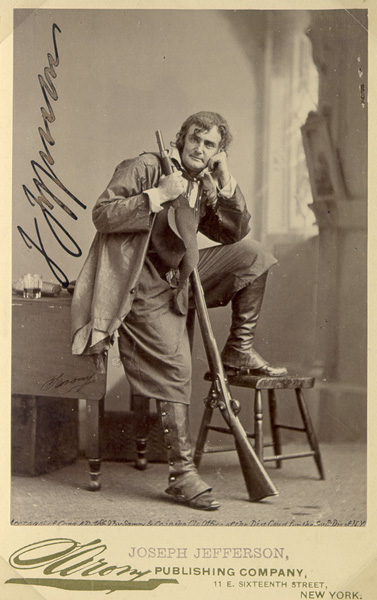

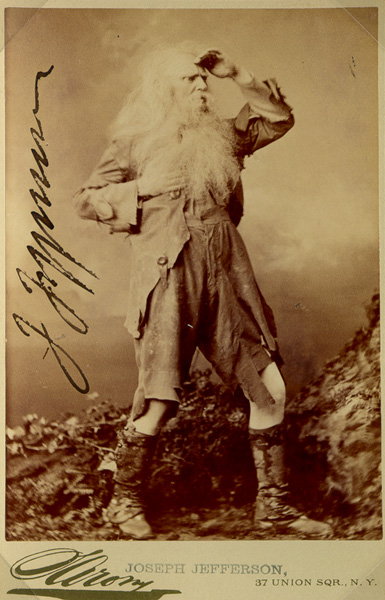

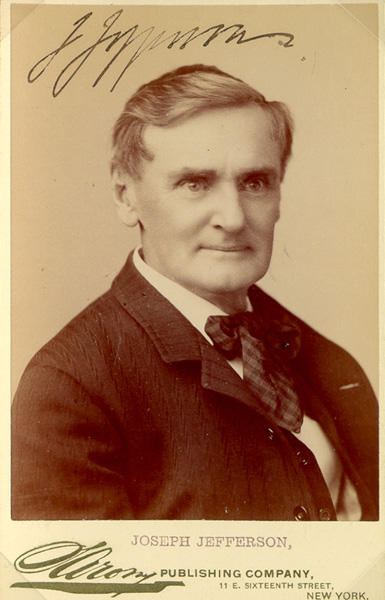

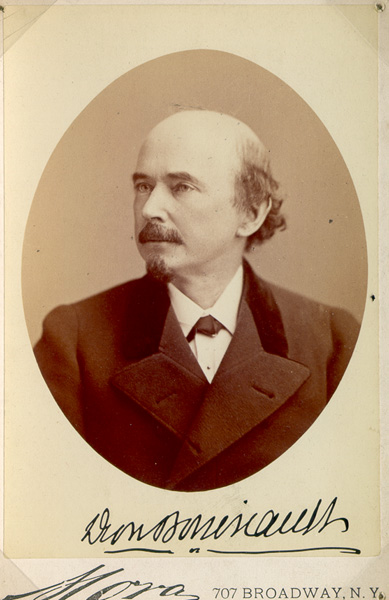

Stage-Struck

Stage-Struck

Stage-Struck

Brother Paul

Brother Paul

Brother Paul

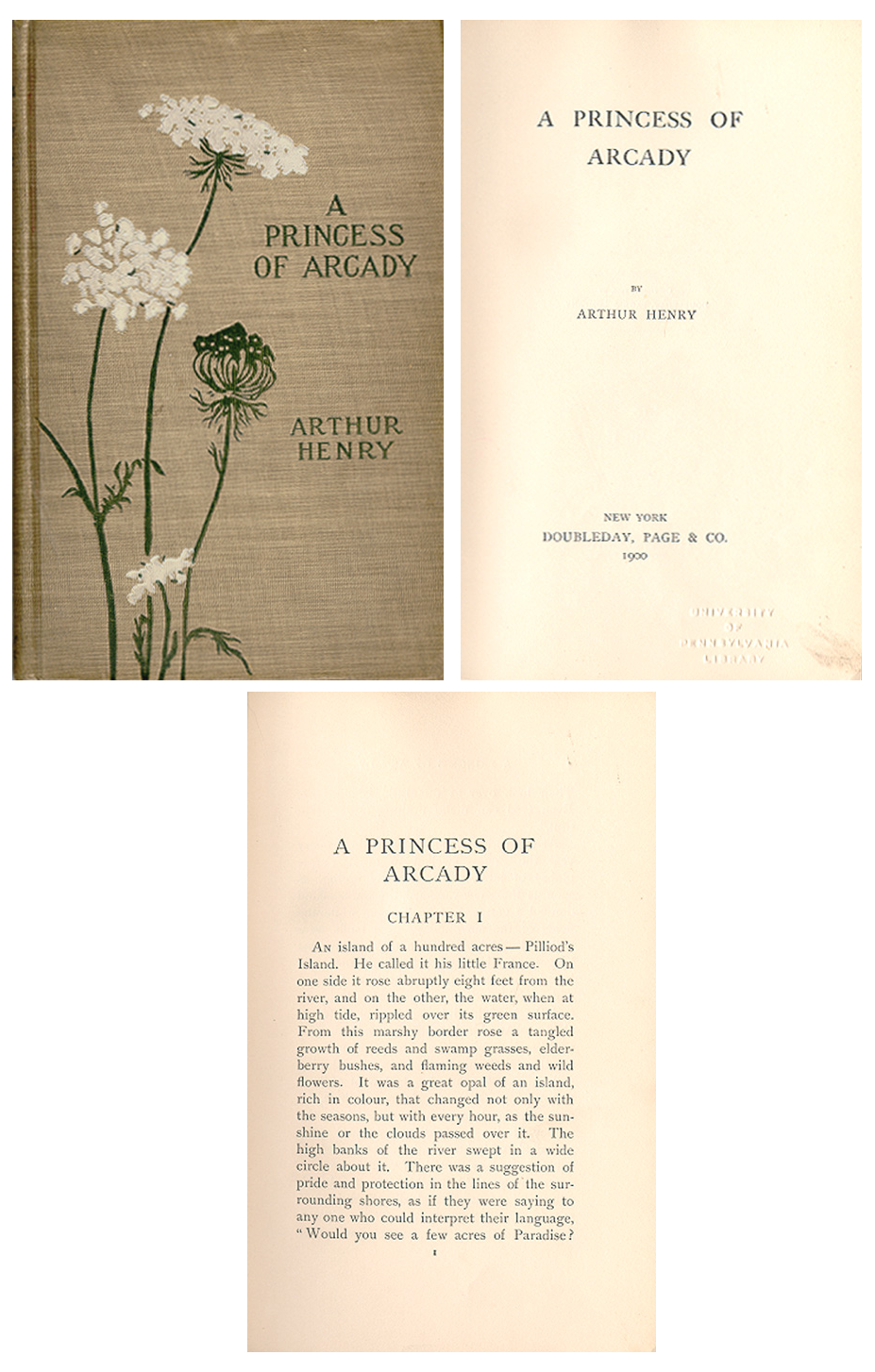

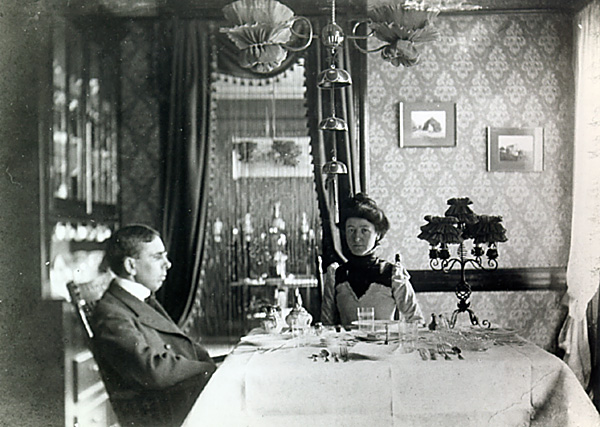

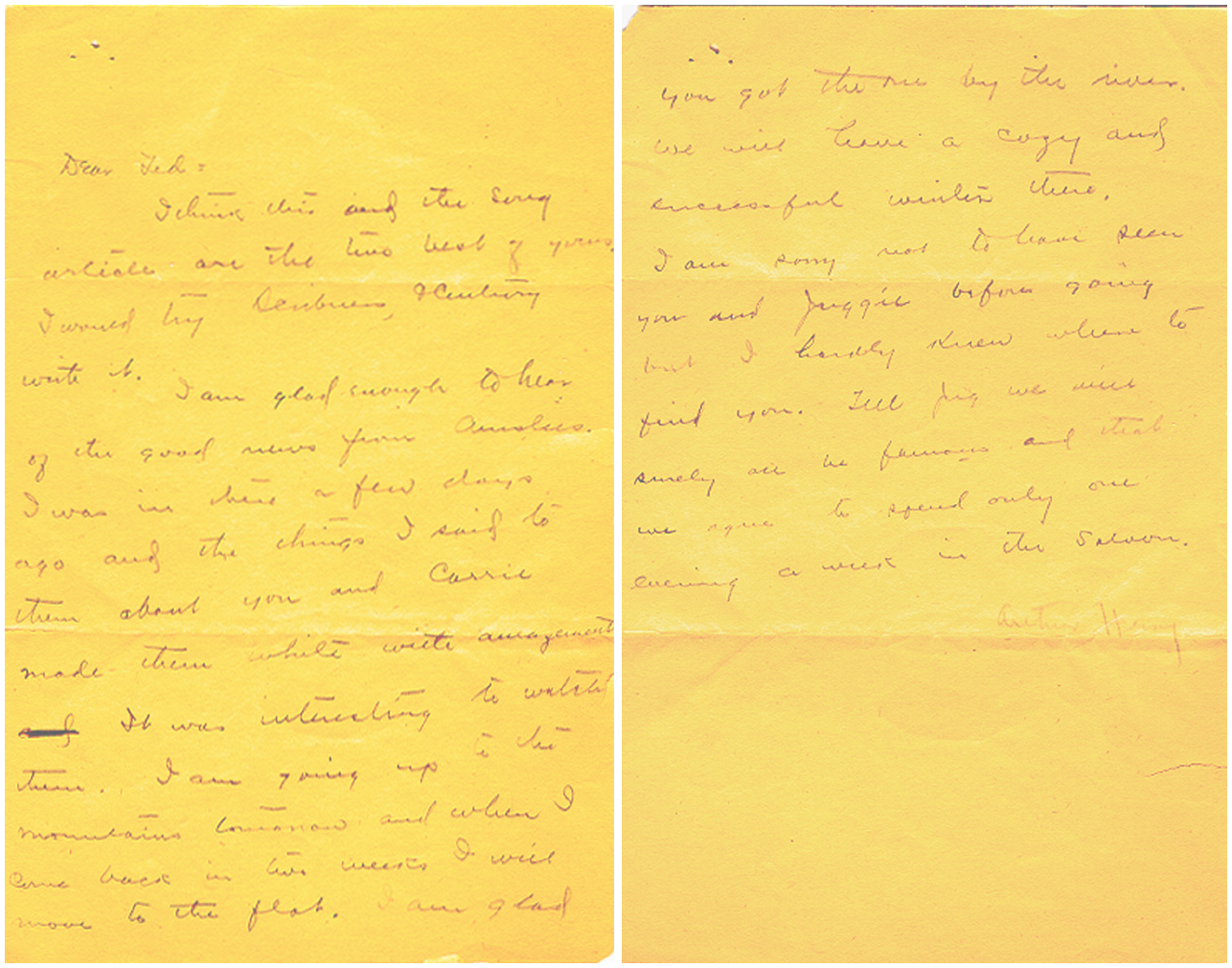

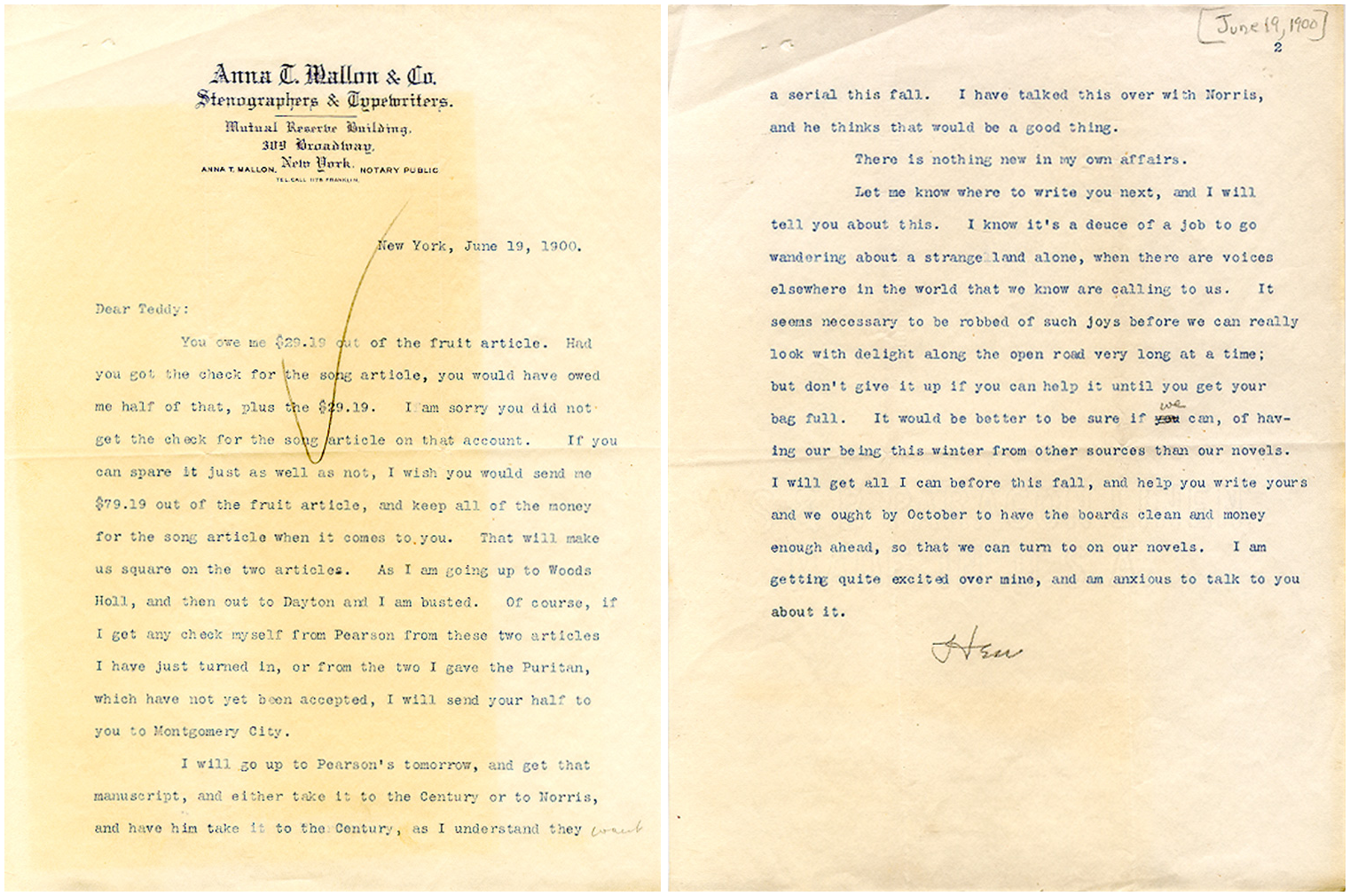

The Enablers - Sara Osbourne White and Arthur Henry

The Enablers - Sara Osbourne White and Arthur Henry

The Enablers - Sara Osbourne White and Arthur Henry

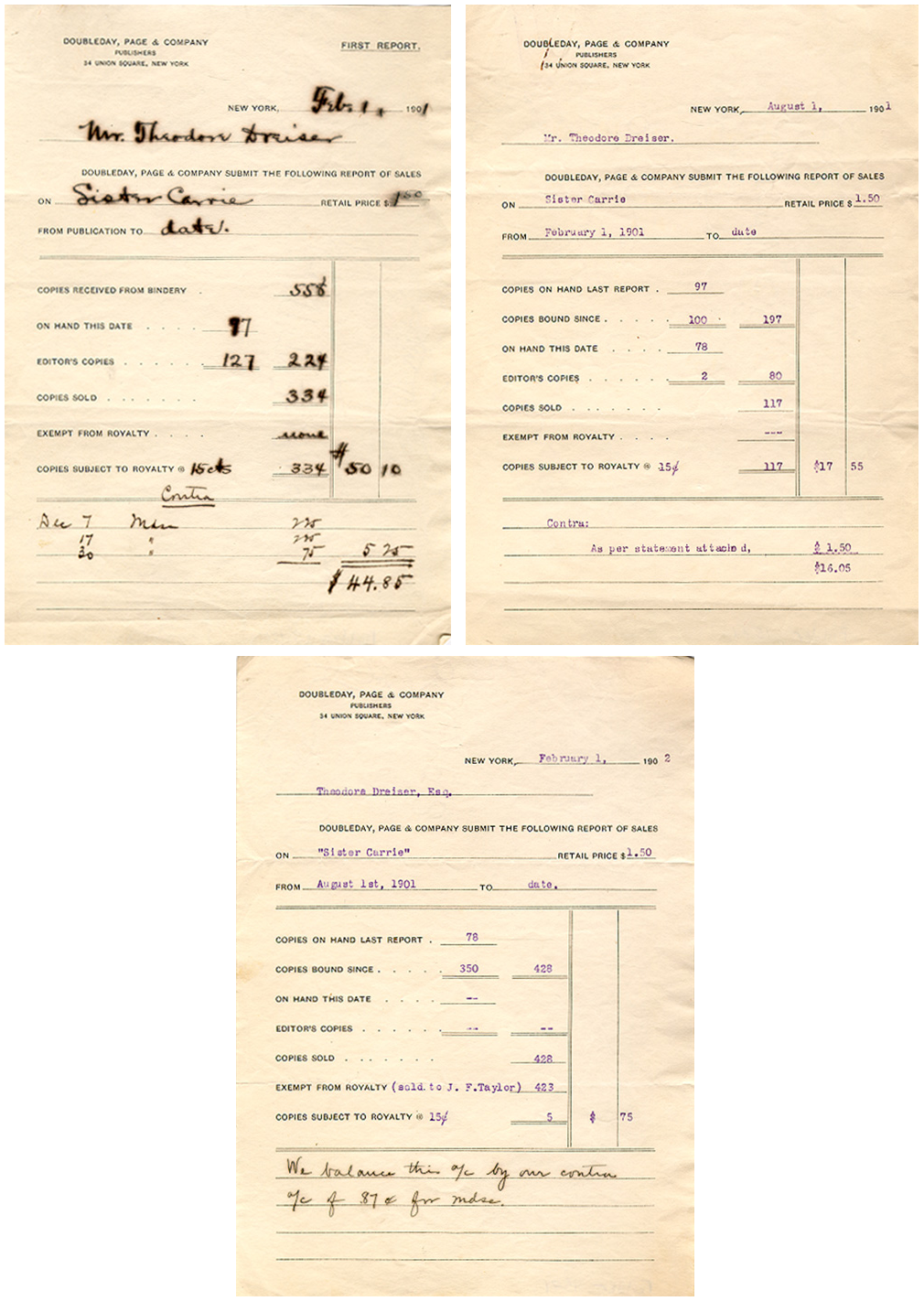

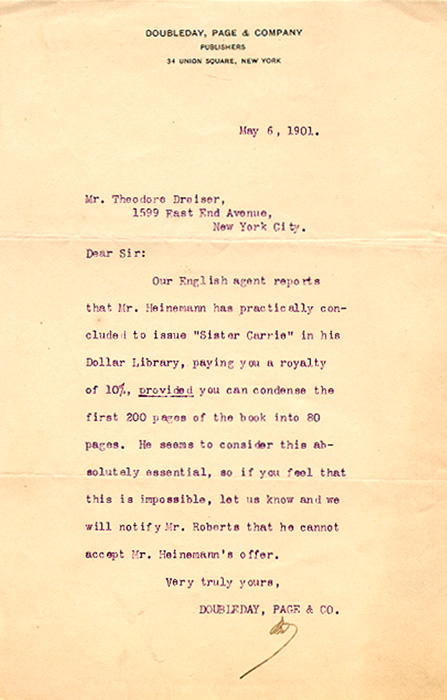

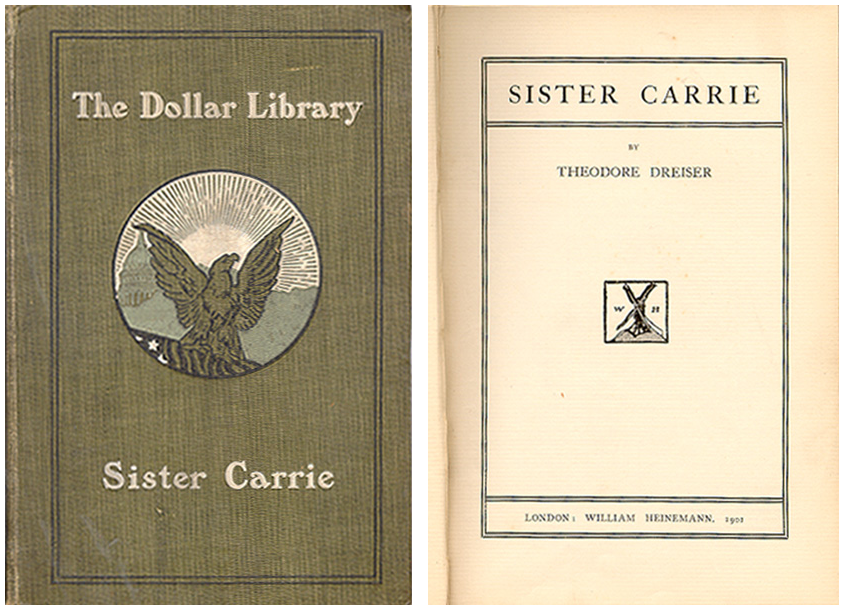

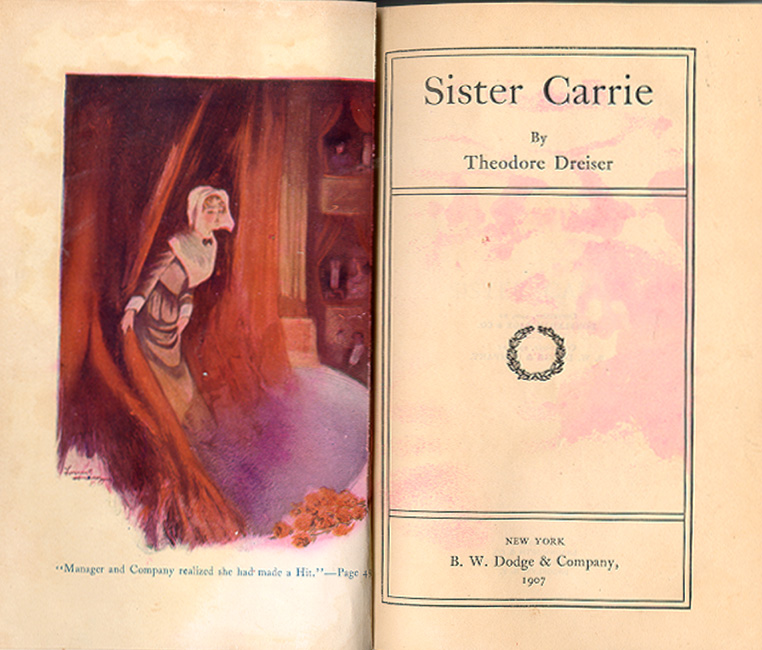

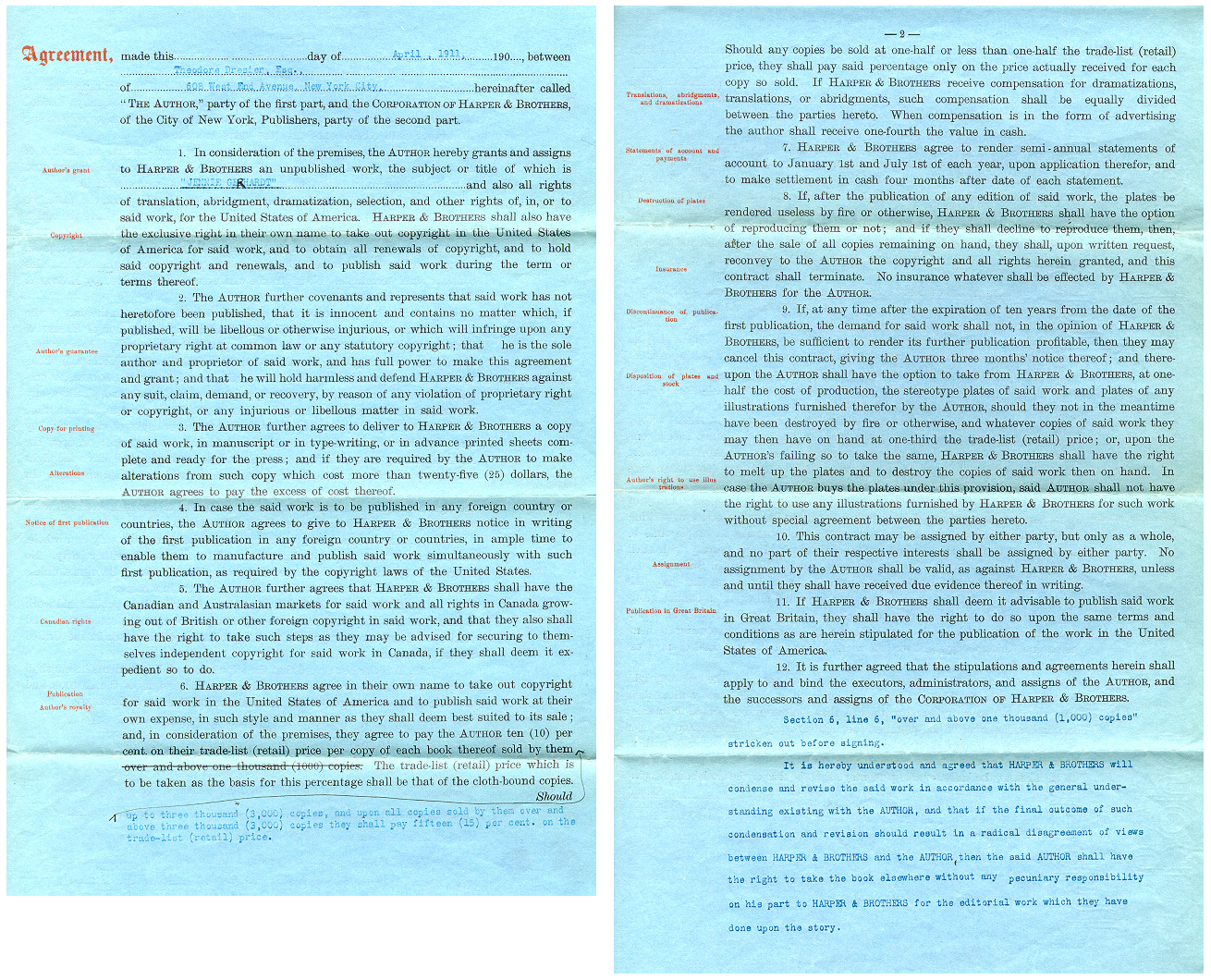

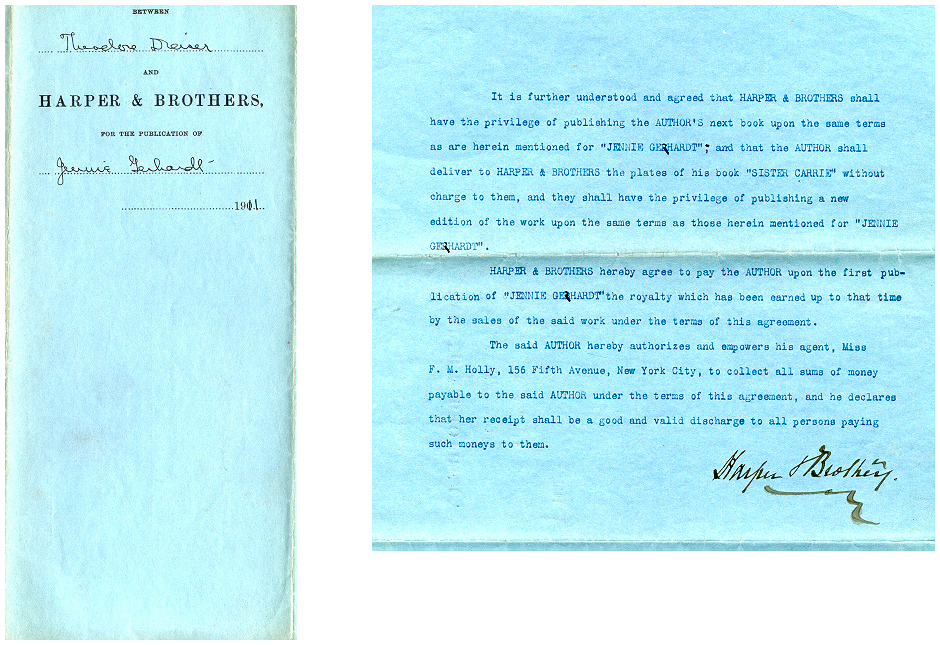

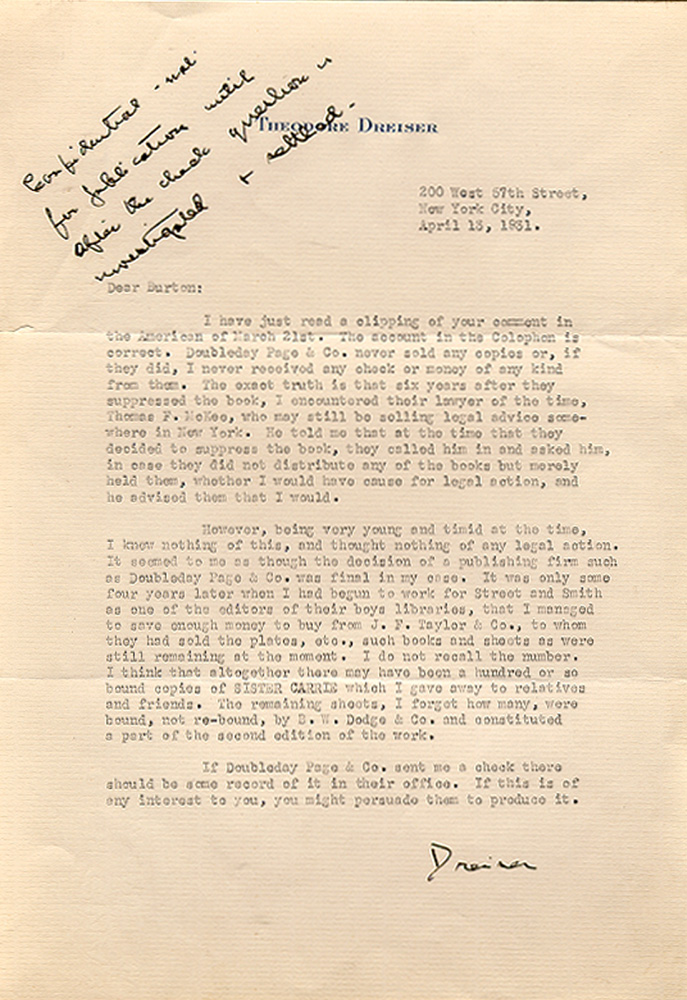

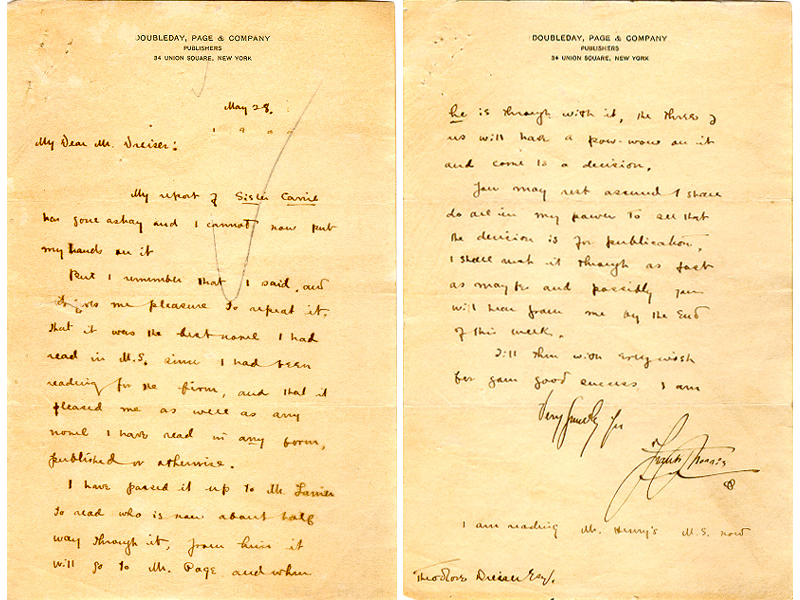

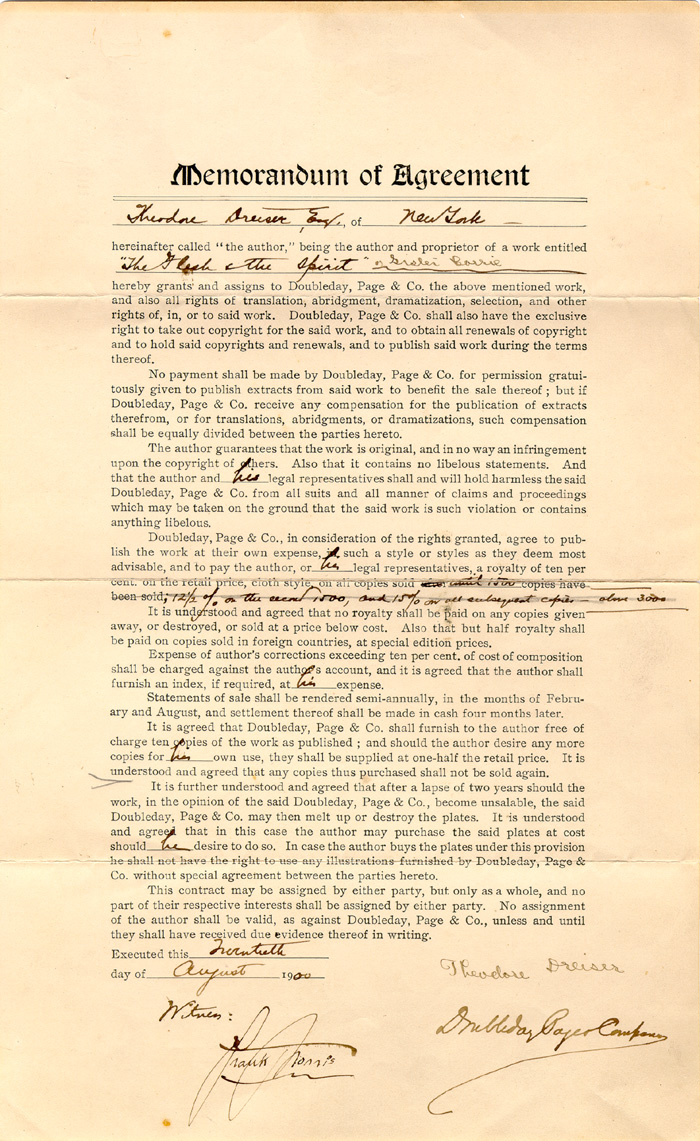

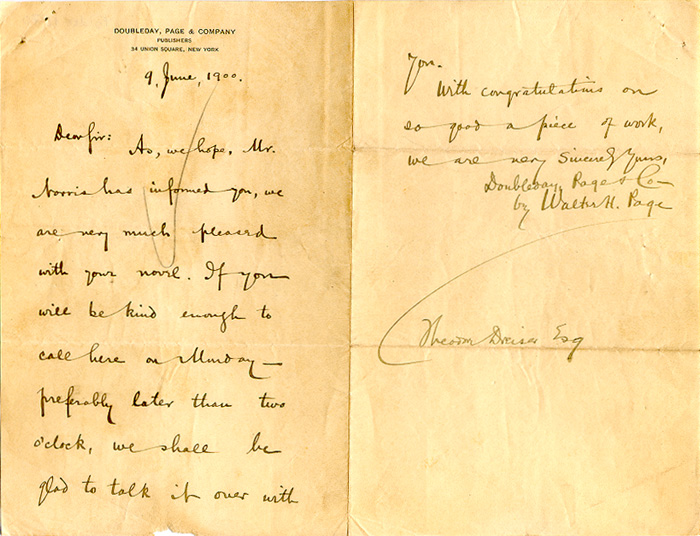

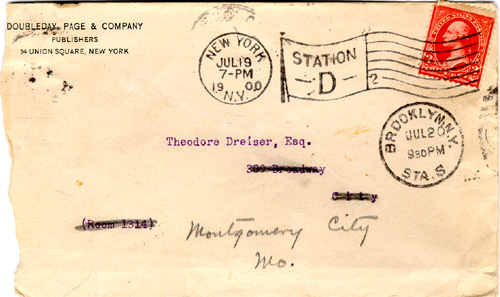

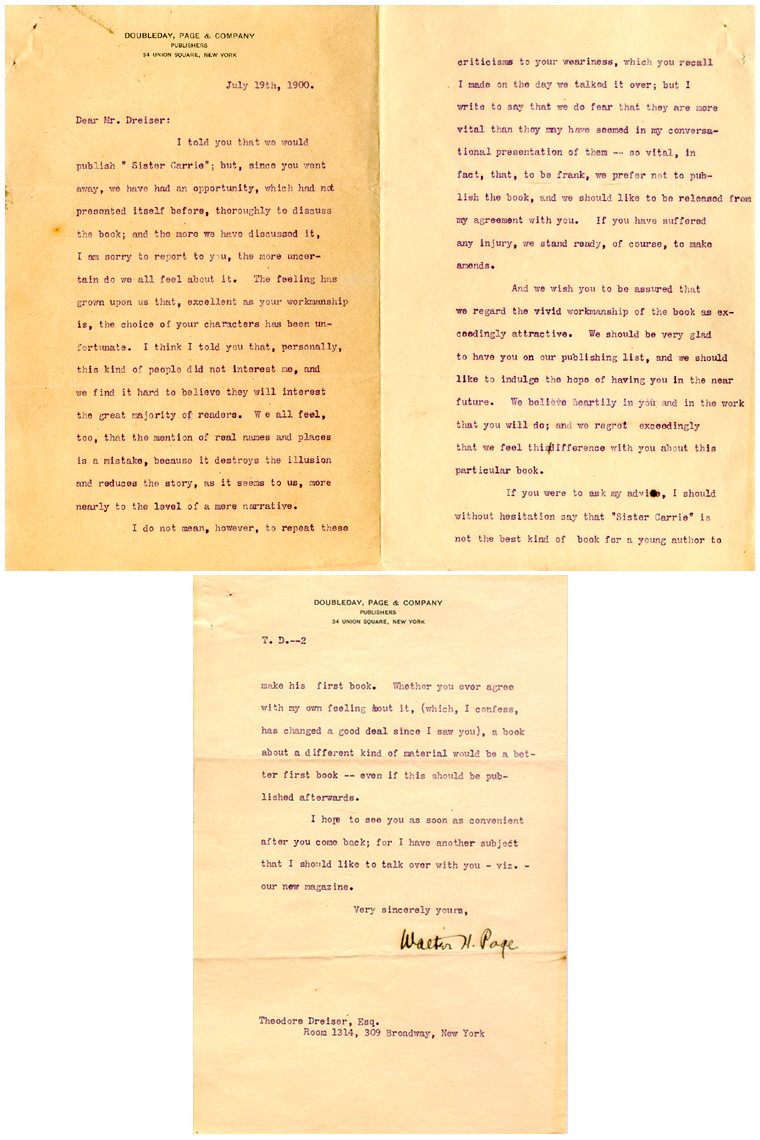

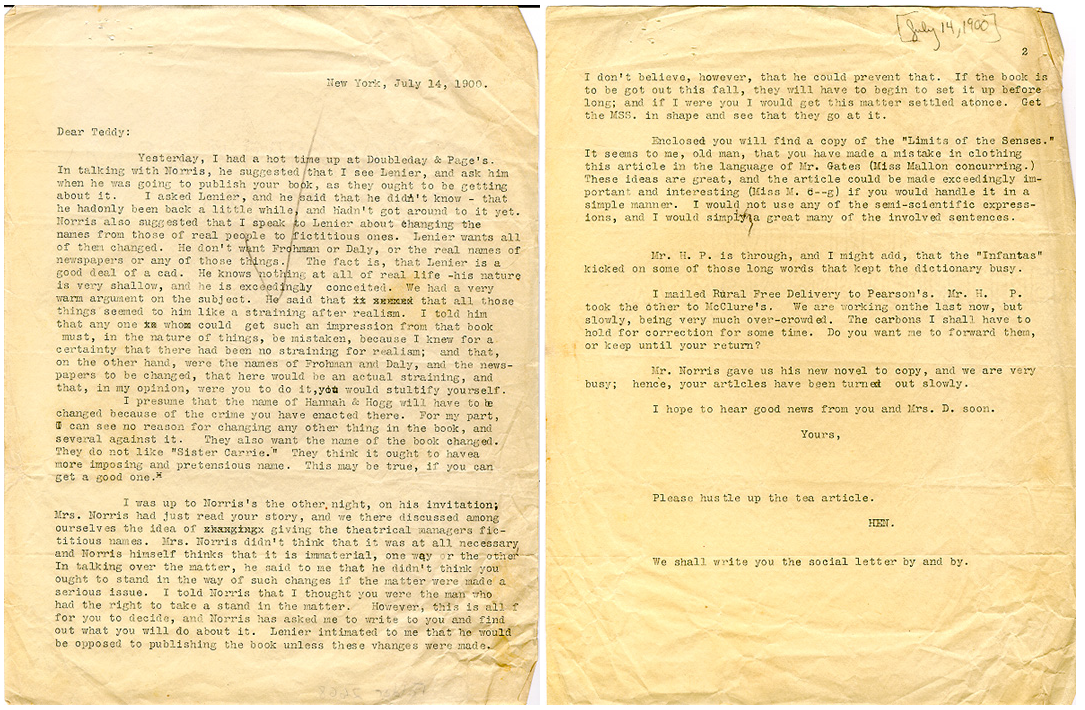

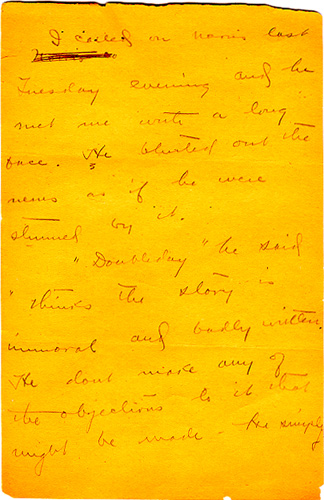

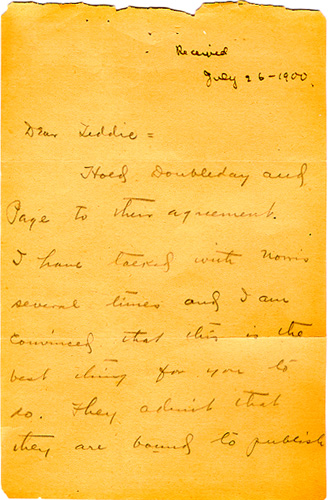

Doubleday, Page and Co. and Beyond

Doubleday, Page and Co. and Beyond

Doubleday, Page and Co. and Beyond

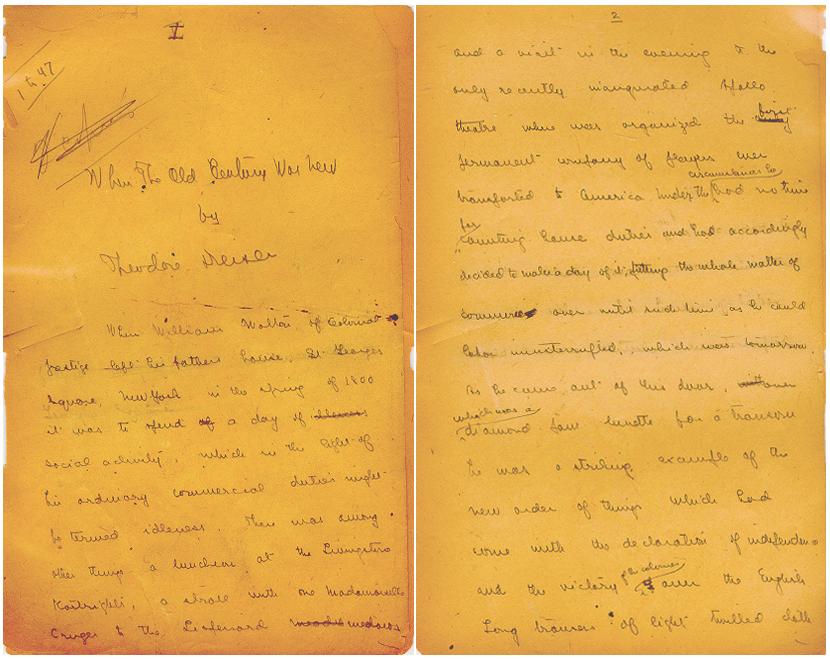

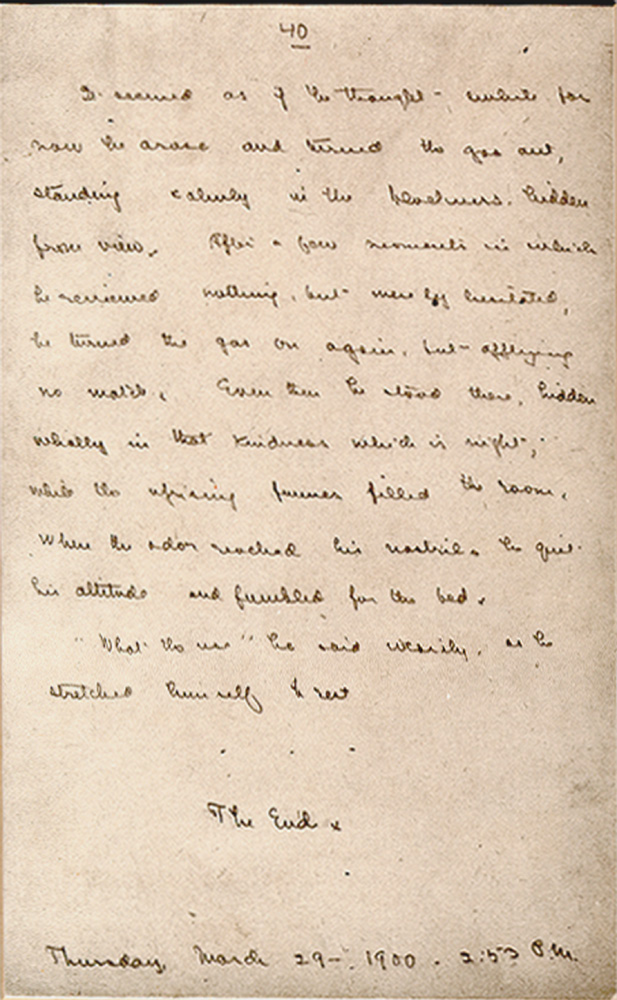

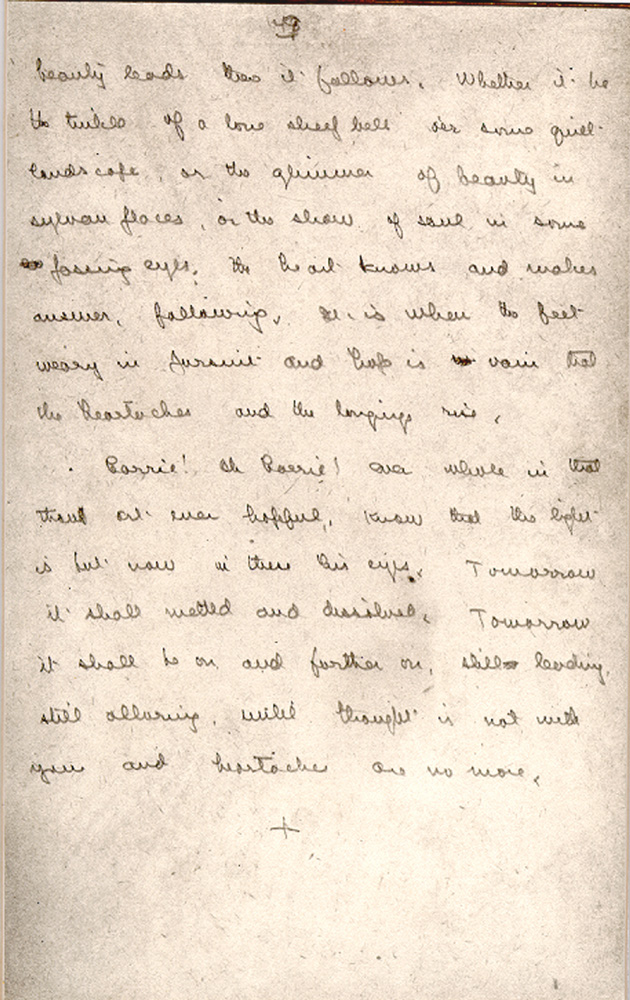

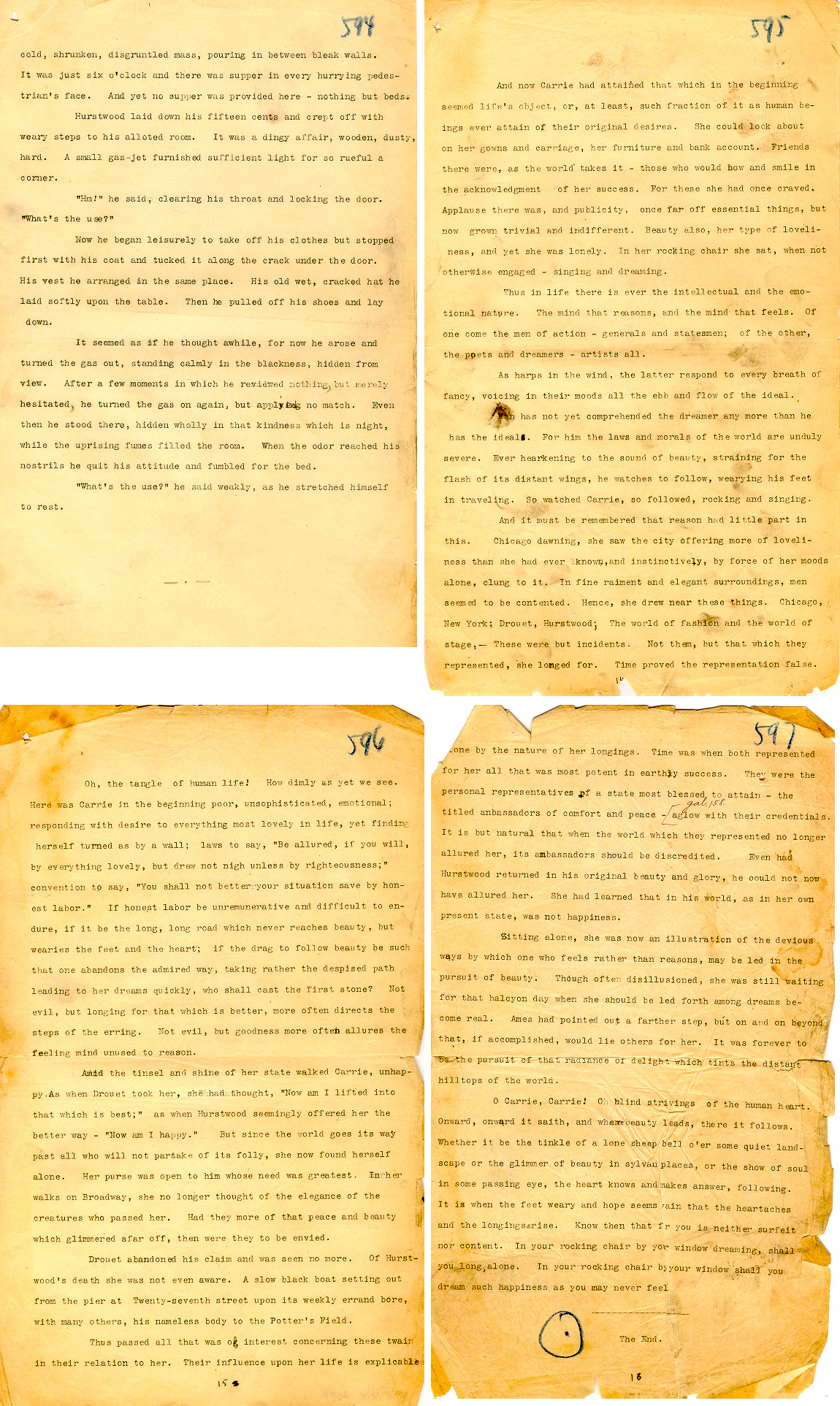

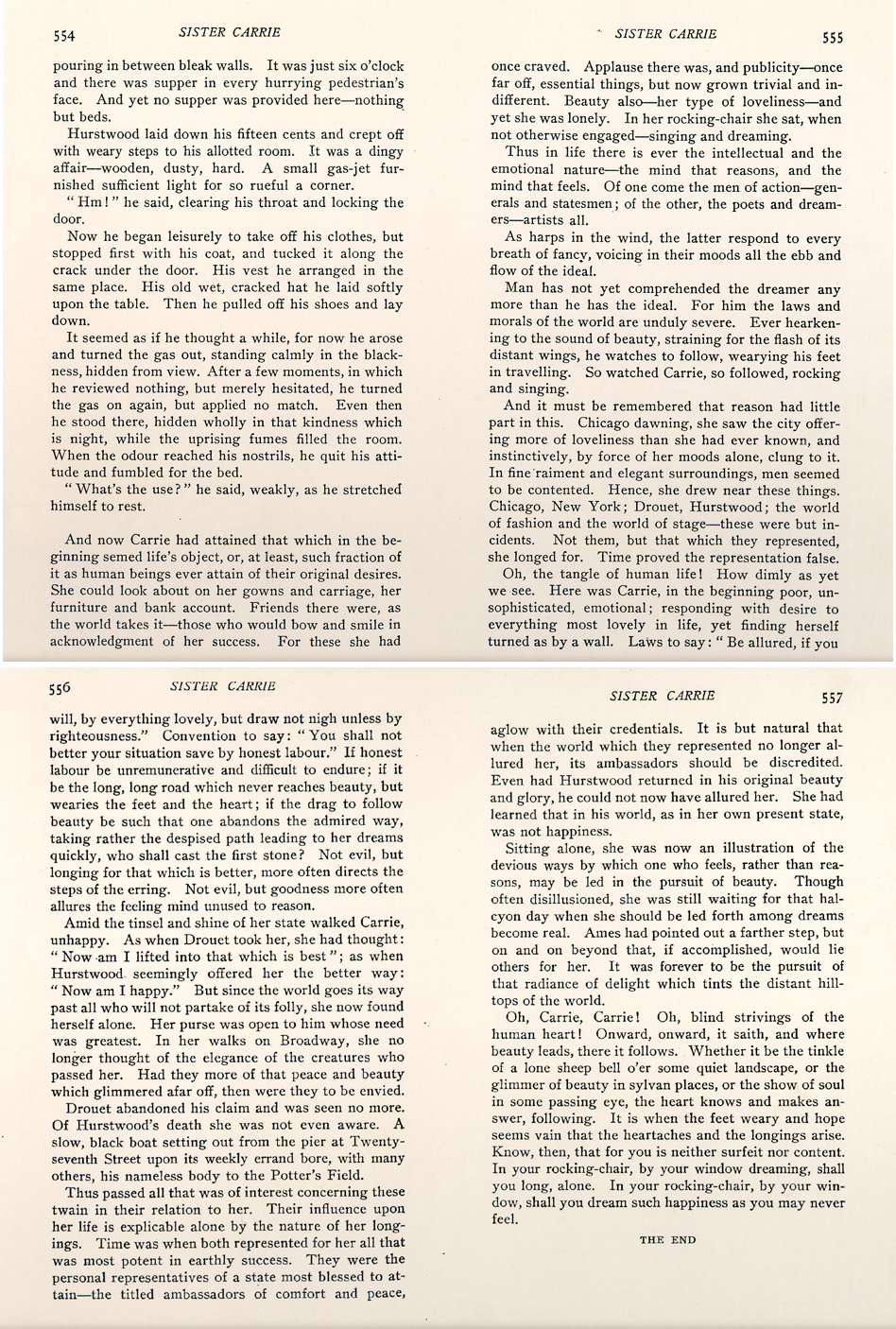

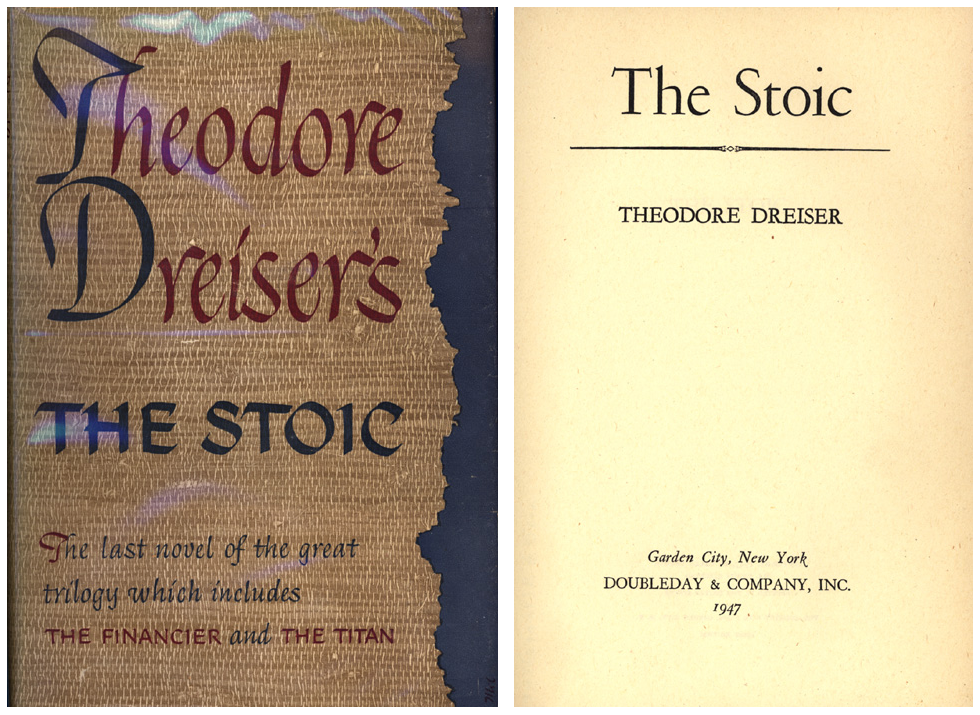

The Last Word

The Last Word

The Last Word

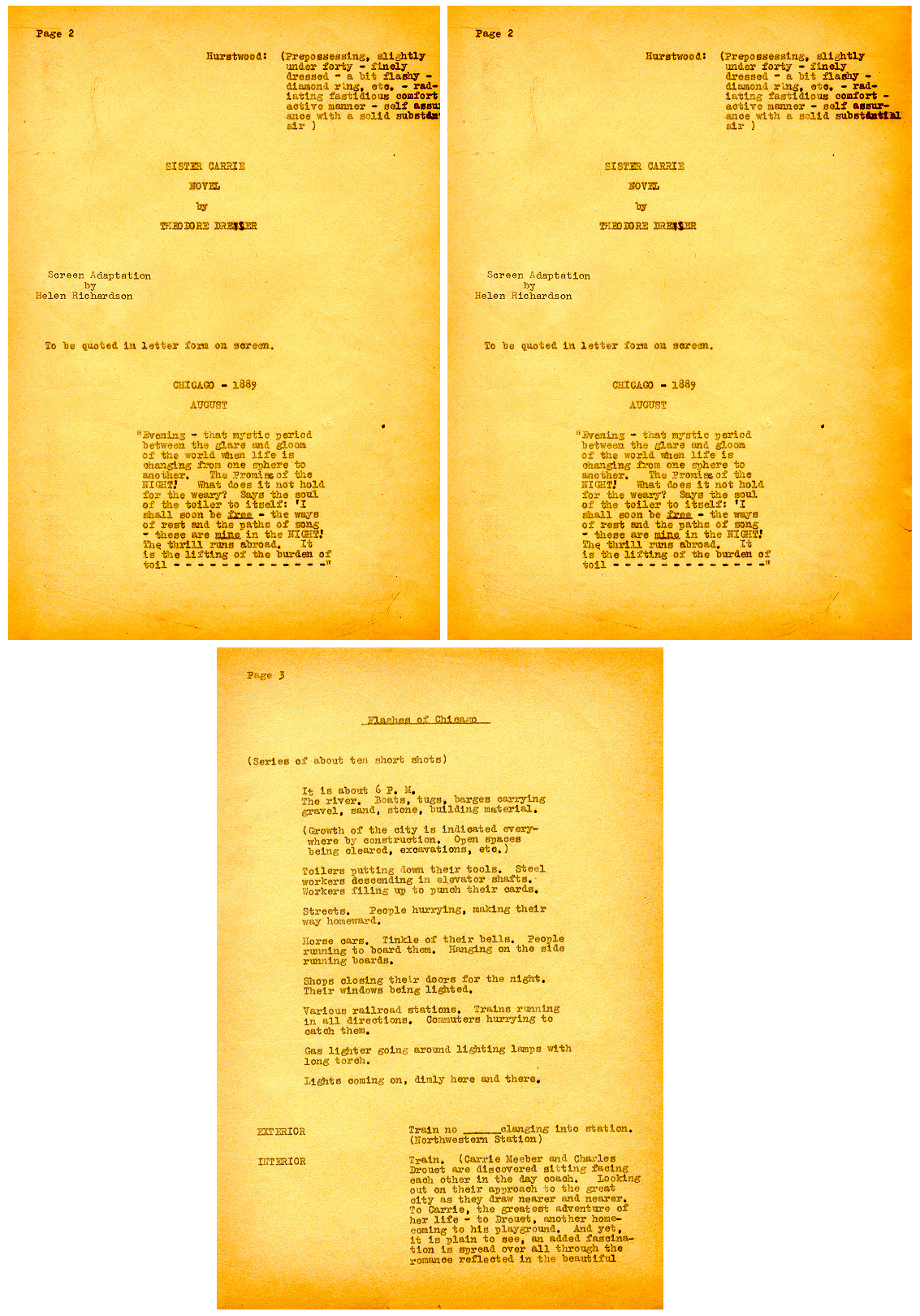

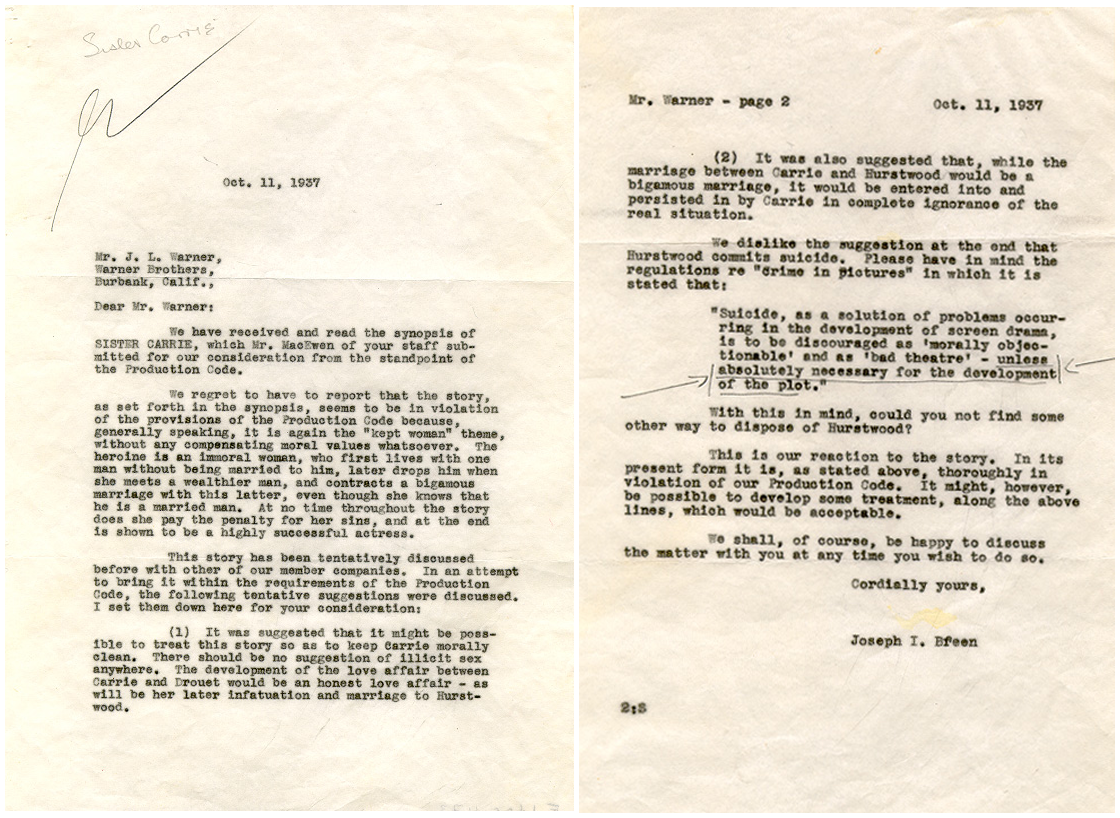

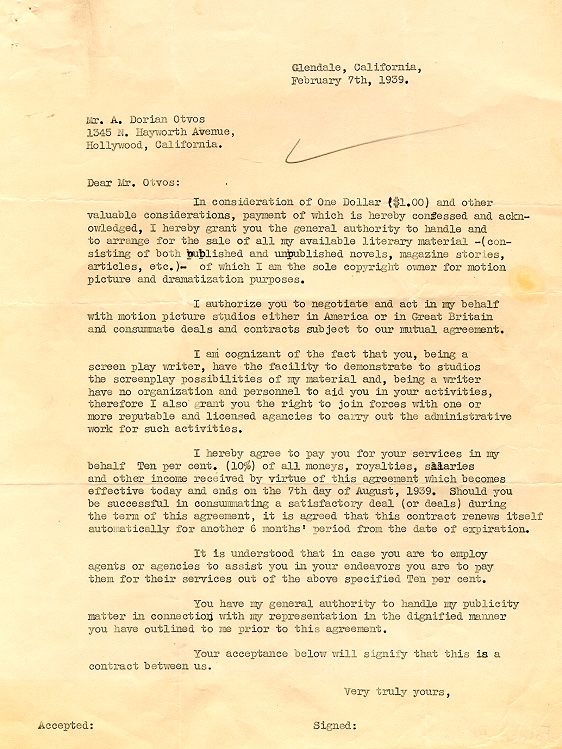

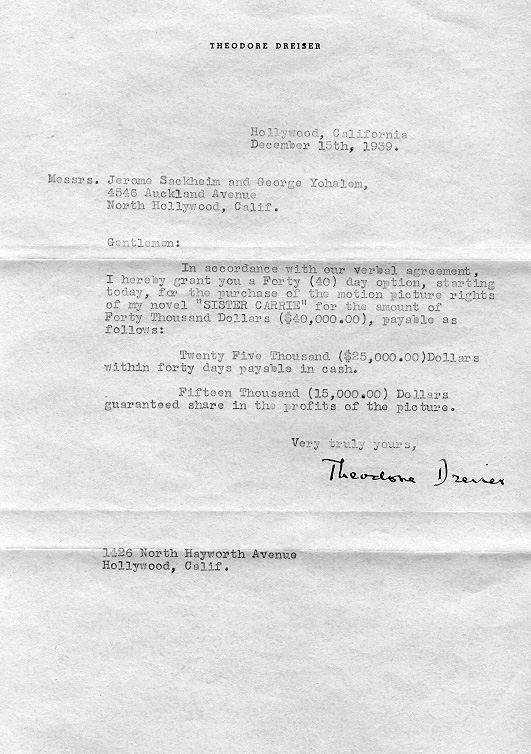

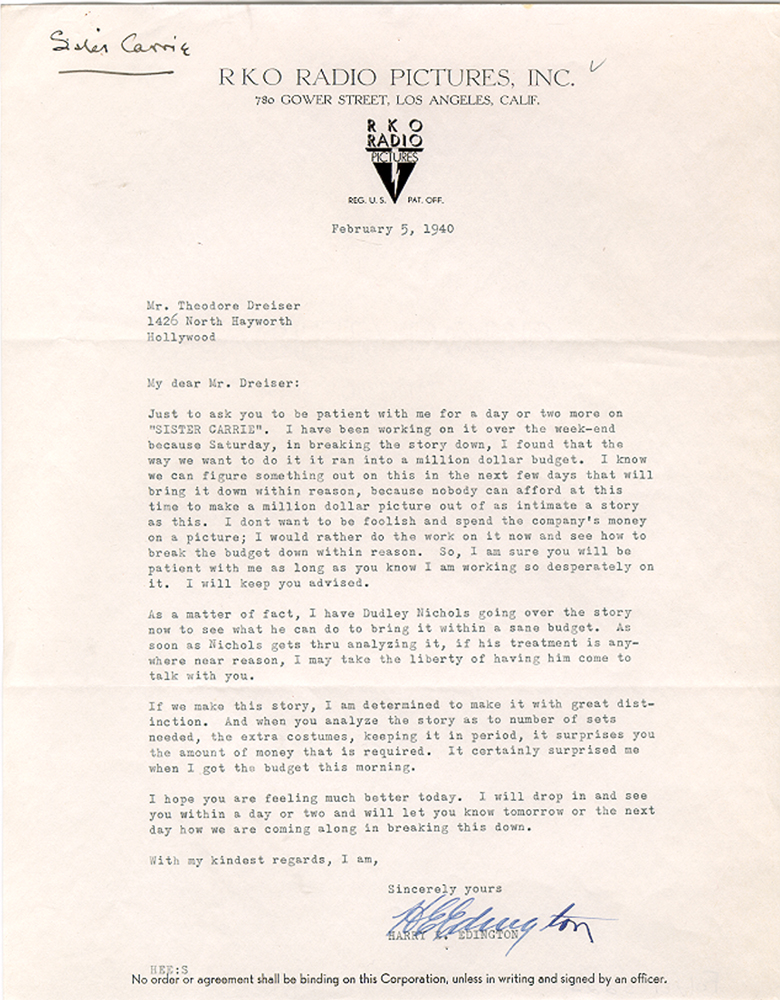

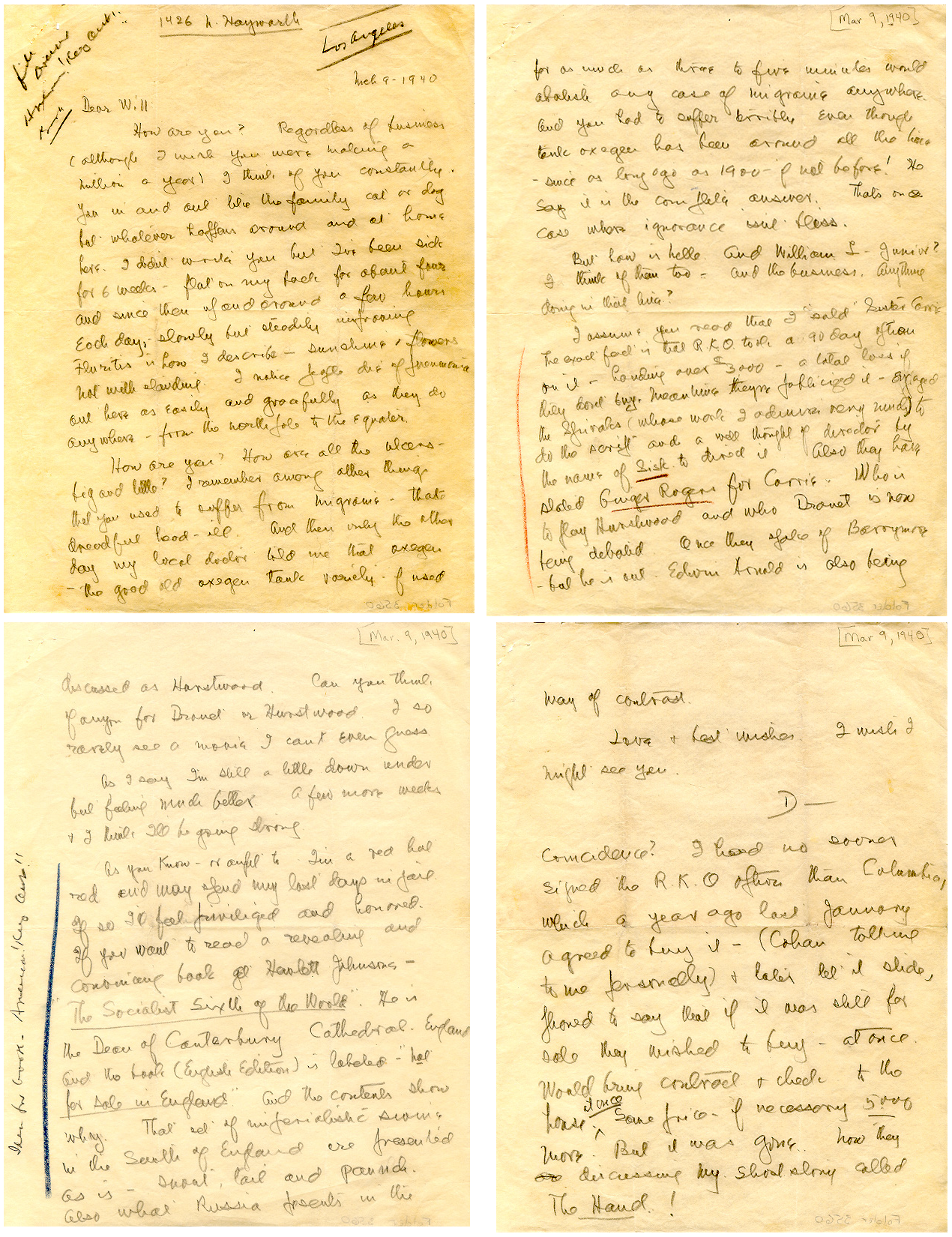

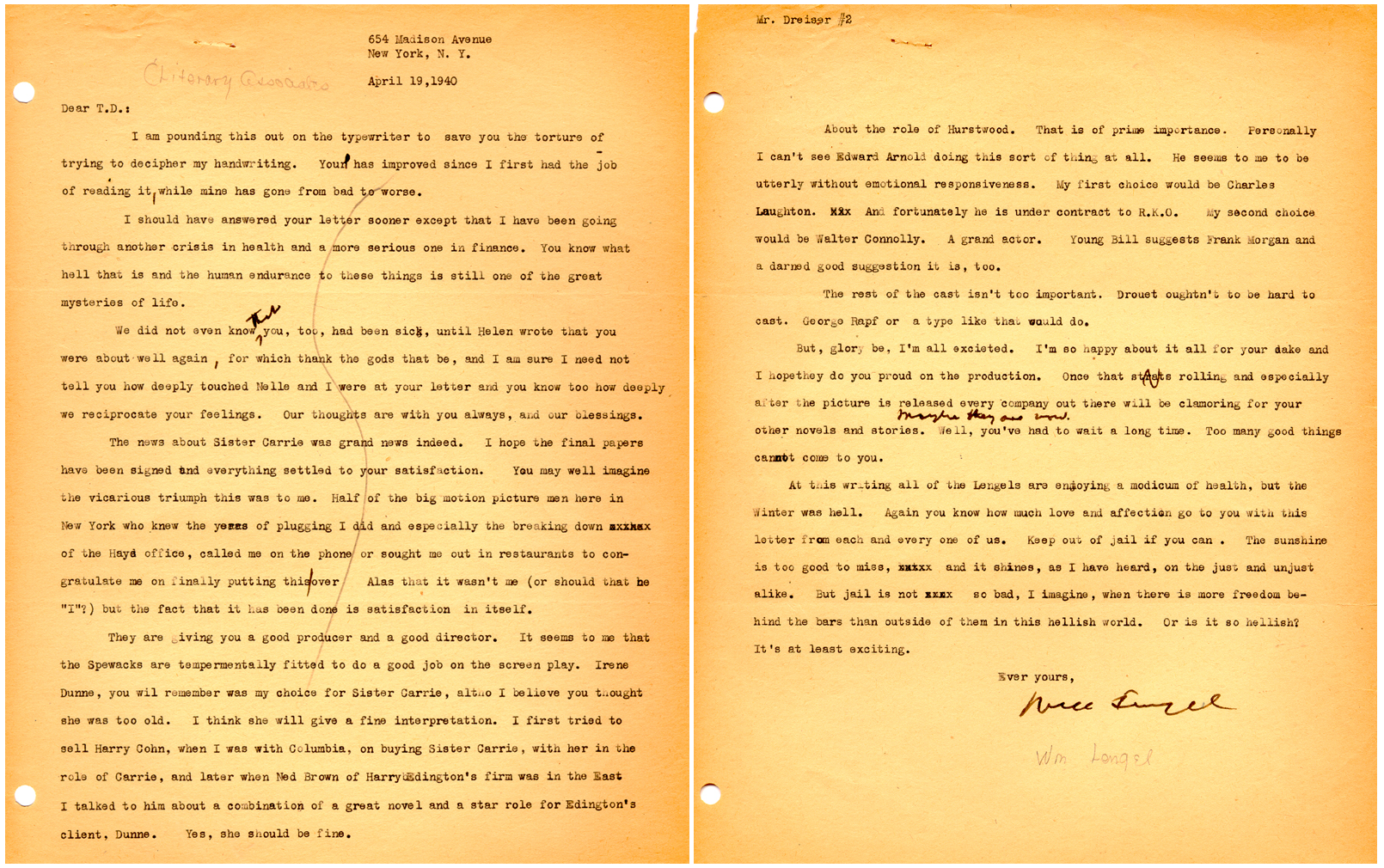

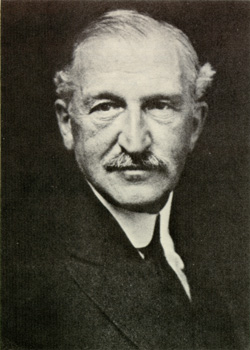

The Hollywoodization of Carrie

The Hollywoodization of Carrie

The Hollywoodization of Carrie

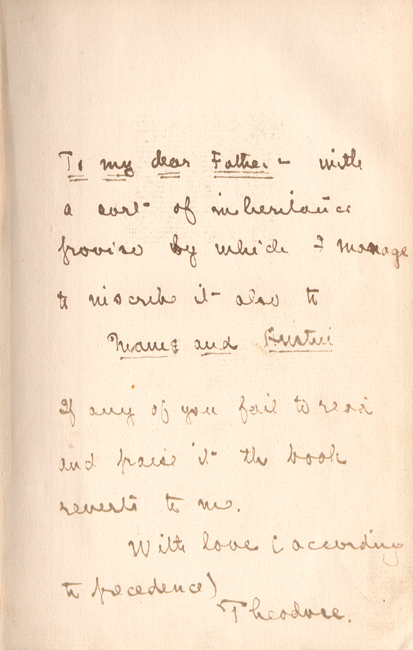

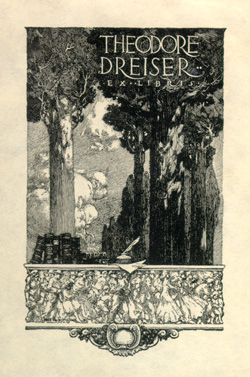

Theodore Dreiser Ex Libris

Theodore Dreiser Ex Libris

Theodore Dreiser Ex Libris

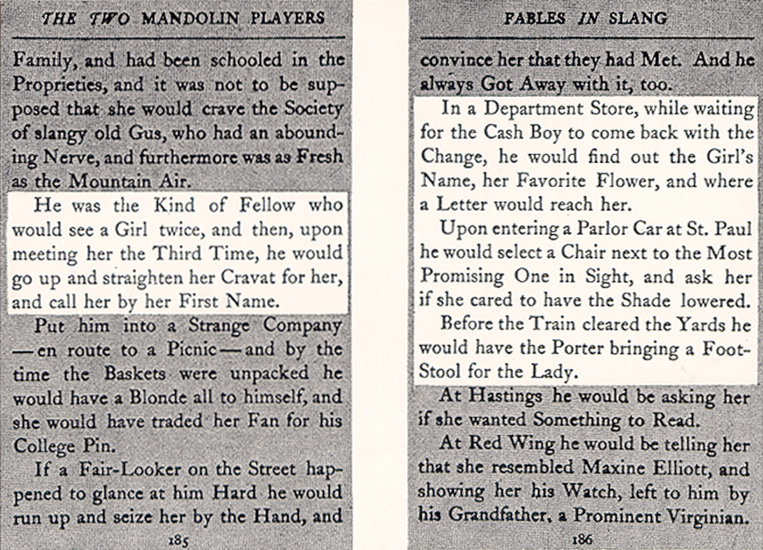

Additional Images

Additional Images

Additional Images

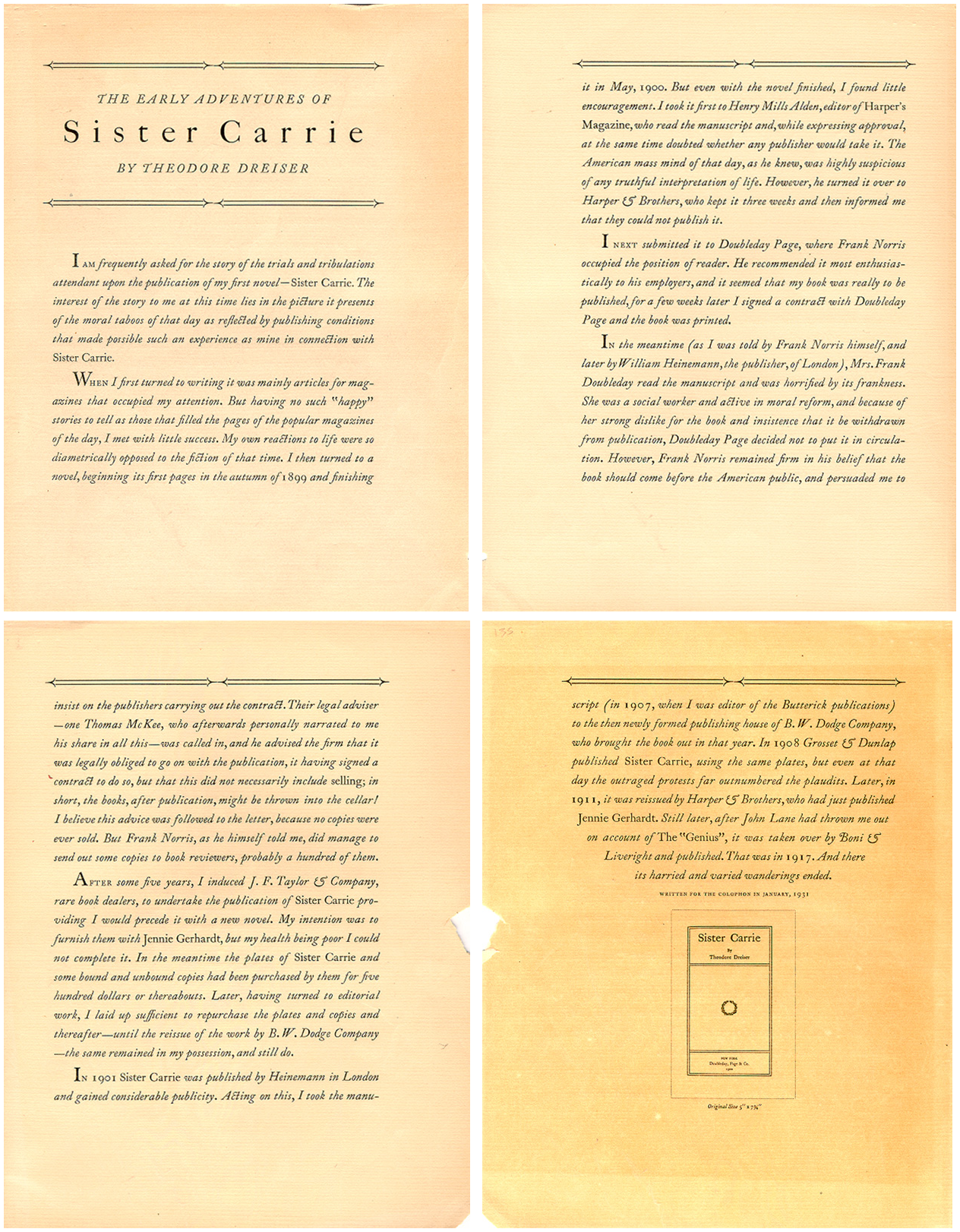

Introduction

One hundred years ago the first novel by American journalist and editor Theodore Dreiser was issued by Doubleday, Page & Co. At the outset the work was primarily distributed to and read by book reviewers. Among the mixed reactions printed in the initial year of publication came a prophetic analysis by William Marion Reedy in the St. Louis Mirror; it was entitled "Sister Carrie: A Strangely Strong Novel in a Queer Milieu" (3 January 1901). Although he admits that the novel is neither "nice" nor "nasty," Reedy identifies one of the enduring powers of Dreiser's tale: "the strong hint of the pathetic in banale situations which is more frequent than often imagined." In a review dominated by plot summary and frequently acknowledging Dreiser's uneven craft, Reedy always returns to his own captivation with Dreiser's remarkable blend of veritism and art: "at times the whole thing is impossible, and then again it is as absolute as life itself."

Sister Carrie remains vital for many reasons: as an historical marker for the turn away from sentimentality, romance, and moral rectitude in the American novel at the brink of the twentieth century; as a text that influenced--pro and con--succeeding American novelists over the next several decades; and as a conundrum that never ceases to provoke debate for readers both general and professional. While the first half of the twentieth century produced a diverse range of critical opinion on Sister Carrie by reviewers and essayists, the second half has been witness to an abiding argument within academia regarding the quality, value, importance, and interpretation of this signature text.

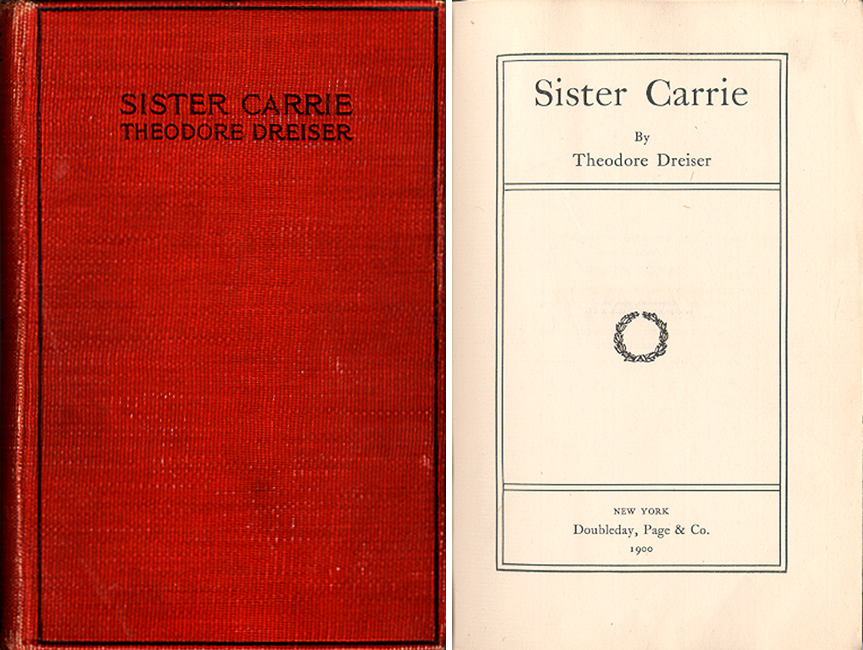

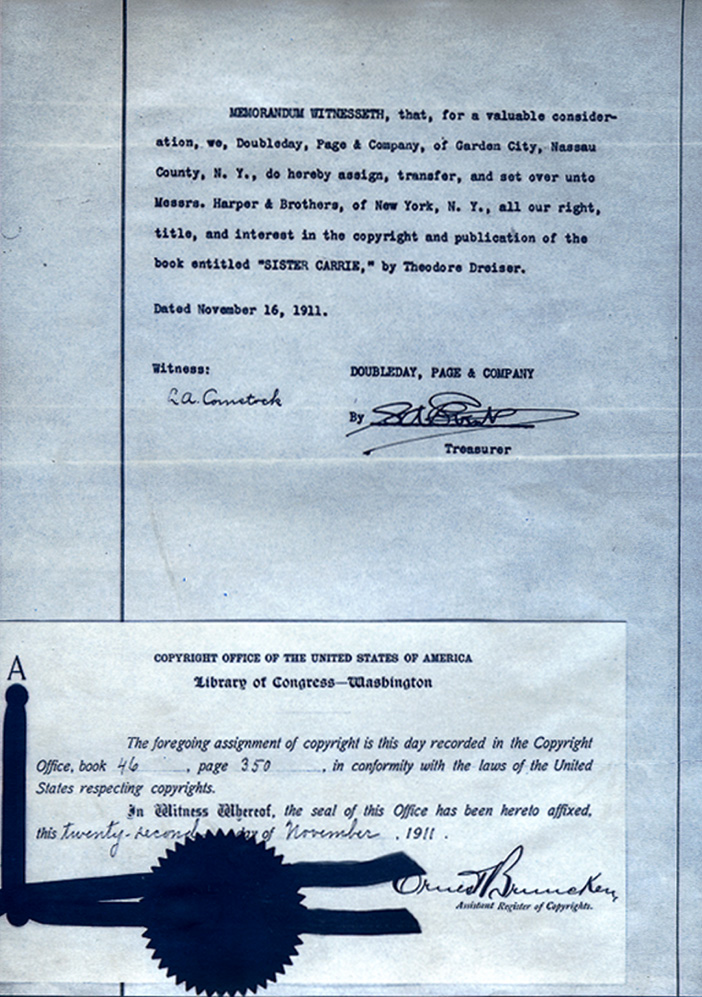

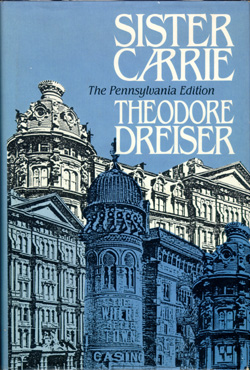

Fig. 1: First edition of the book that Frank Doubleday never wanted to publish and did nothing to promote.

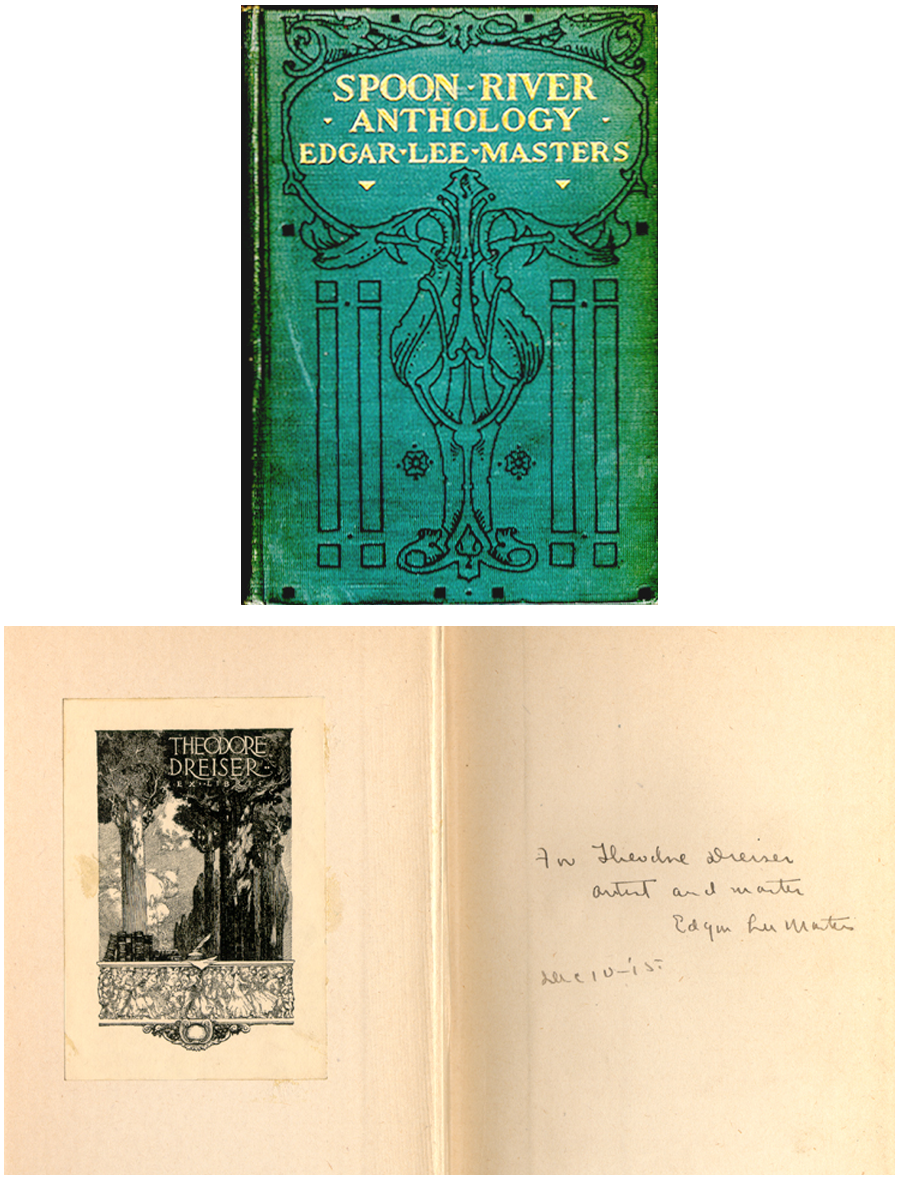

Fig. 2: First edition of Masters' book of poems inscribed by Masters to Theodore Dreiser: "For Theodore Dreiser/ artist and master/ Edgar Lee Masters/ Dec 10-'15"

Fig. 3: Edgar Lee Masters was a Chicago lawyer who composed poetry (which he published himself) when he wrote Dreiser in 1912 to praise a recent Dreiser publication, The Financier. In the first page of his letter, he notes that he had followed Dreiser's novels from the beginning, when he found himself absorbed by Sister Carrie. He continues: "You have such a capacity for detail and for the pure fact from which truth is secreted that you pile up in tireless fashion the evidence for your argument."

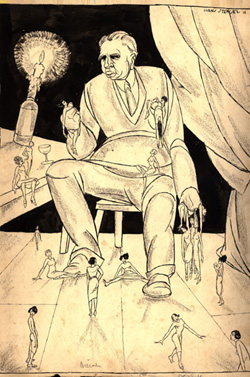

Fig. 5: This caricature of the two American novelists mocks their realist style, which was often found too frank and unrelenting for popular taste. The drawing was used in the Book Review section of the New York Times on 5 September 1926 with the title "Merciless Realism" and the caption "Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson Watching People Suffer."

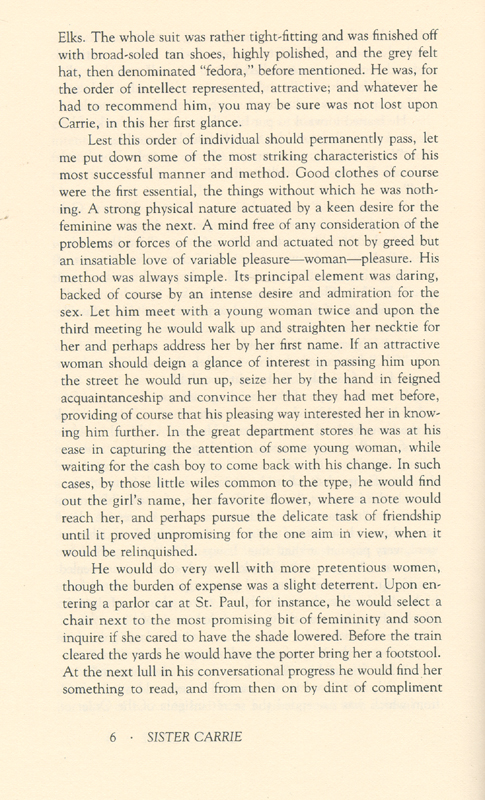

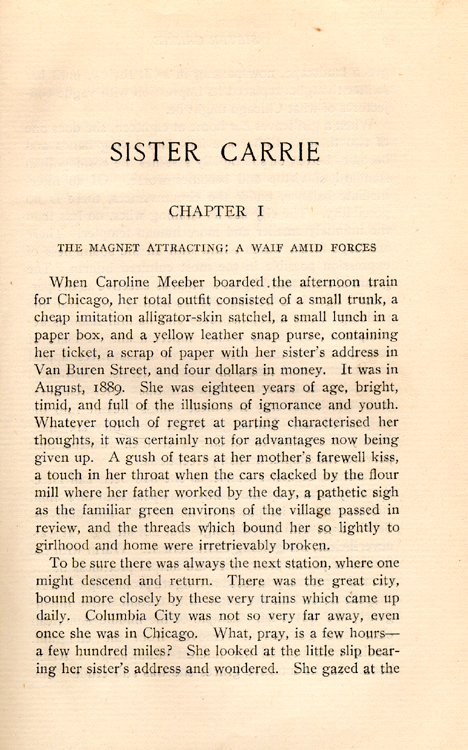

Fig. 1: First edition of the book that Frank Doubleday never wanted to publish and did nothing to promote.

Fig. 2: First edition of Masters' book of poems inscribed by Masters to Theodore Dreiser: "For Theodore Dreiser/ artist and master/ Edgar Lee Masters/ Dec 10-'15"

Fig. 3: Edgar Lee Masters was a Chicago lawyer who composed poetry (which he published himself) when he wrote Dreiser in 1912 to praise a recent Dreiser publication, The Financier. In the first page of his letter, he notes that he had followed Dreiser's novels from the beginning, when he found himself absorbed by Sister Carrie. He continues: "You have such a capacity for detail and for the pure fact from which truth is secreted that you pile up in tireless fashion the evidence for your argument."

Fig. 5: This caricature of the two American novelists mocks their realist style, which was often found too frank and unrelenting for popular taste. The drawing was used in the Book Review section of the New York Times on 5 September 1926 with the title "Merciless Realism" and the caption "Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson Watching People Suffer."

Fig. 1: First edition of the book that Frank Doubleday never wanted to publish and did nothing to promote.

Fig. 2: First edition of Masters' book of poems inscribed by Masters to Theodore Dreiser: "For Theodore Dreiser/ artist and master/ Edgar Lee Masters/ Dec 10-'15"

Fig. 3: Edgar Lee Masters was a Chicago lawyer who composed poetry (which he published himself) when he wrote Dreiser in 1912 to praise a recent Dreiser publication, The Financier. In the first page of his letter, he notes that he had followed Dreiser's novels from the beginning, when he found himself absorbed by Sister Carrie. He continues: "You have such a capacity for detail and for the pure fact from which truth is secreted that you pile up in tireless fashion the evidence for your argument."

Fig. 5: This caricature of the two American novelists mocks their realist style, which was often found too frank and unrelenting for popular taste. The drawing was used in the Book Review section of the New York Times on 5 September 1926 with the title "Merciless Realism" and the caption "Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson Watching People Suffer."

Fig. 1: First edition of the book that Frank Doubleday never wanted to publish and did nothing to promote.

Fig. 2: First edition of Masters' book of poems inscribed by Masters to Theodore Dreiser: "For Theodore Dreiser/ artist and master/ Edgar Lee Masters/ Dec 10-'15"

Fig. 3: Edgar Lee Masters was a Chicago lawyer who composed poetry (which he published himself) when he wrote Dreiser in 1912 to praise a recent Dreiser publication, The Financier. In the first page of his letter, he notes that he had followed Dreiser's novels from the beginning, when he found himself absorbed by Sister Carrie. He continues: "You have such a capacity for detail and for the pure fact from which truth is secreted that you pile up in tireless fashion the evidence for your argument."

Fig. 5: This caricature of the two American novelists mocks their realist style, which was often found too frank and unrelenting for popular taste. The drawing was used in the Book Review section of the New York Times on 5 September 1926 with the title "Merciless Realism" and the caption "Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson Watching People Suffer."

Fig. 1: First edition of the book that Frank Doubleday never wanted to publish and did nothing to promote.

Fig. 2: First edition of Masters' book of poems inscribed by Masters to Theodore Dreiser: "For Theodore Dreiser/ artist and master/ Edgar Lee Masters/ Dec 10-'15"

Fig. 3: Edgar Lee Masters was a Chicago lawyer who composed poetry (which he published himself) when he wrote Dreiser in 1912 to praise a recent Dreiser publication, The Financier. In the first page of his letter, he notes that he had followed Dreiser's novels from the beginning, when he found himself absorbed by Sister Carrie. He continues: "You have such a capacity for detail and for the pure fact from which truth is secreted that you pile up in tireless fashion the evidence for your argument."

Fig. 5: This caricature of the two American novelists mocks their realist style, which was often found too frank and unrelenting for popular taste. The drawing was used in the Book Review section of the New York Times on 5 September 1926 with the title "Merciless Realism" and the caption "Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson Watching People Suffer."

Before publishing his first novel, Dreiser's apprenticeship in writing comprised a menagerie of short-term assignments and positions with newspapers and magazines from St. Louis to New York. His first reporter's job came in 1892 with the Chicago Daily Globe, considered one of the weakest of the Chicago papers at the time. But the Globe's less-than-premiere status afforded the inexperienced writer the opportunity to prove himself. He parlayed his few months of work at the Chicago Daily Globe into a position at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a morning Republican paper that was the biggest in town. At one point Dreiser was assigned the "hotel beat," which meant interviewing visiting celebrities. After returning to the city room one night, having just interviewed the theosophist Annie Besant, he was called away to cover a triple murder. Still dressed in his rented evening clothes, Dreiser arrived at the scene of the crime to find the bloody corpses of a mother and her two children who had been brutally murdered by her husband, the children's father. This dichotomy between wealth and poverty, between appearance and reality, between prospects and hopelessness informs Sister Carrie.

The life of the newspaperman in Dreiser's time was itself filled with poverty, lasciviousness, and corruption, as were many of the events that a reporter covered. At first naïve, Dreiser quickly learned the ropes and the realities of urban America, but invariably his ideals or vision or personal pride created rifts between himself and management. Freedom--or what appeared to be freedom--to write works to his own plan drove Dreiser not only to seek the editorship at Ev'ry Month but also to pursue creative writing, such as poetry. After departing Ev'ry Monthin September 1897, Dreiser wrote scores of articles for all manner of publications, always hoping that he could find a measure of financial freedom to write his first novel. Among these works came material that would latter be incorporated into Sister Carrie, which he began in earnest in the fall of 1899.

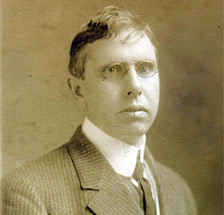

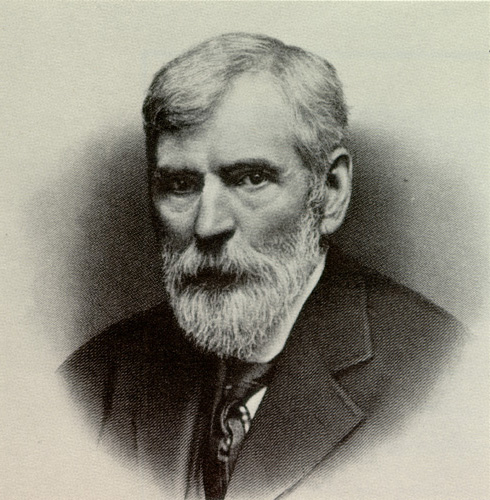

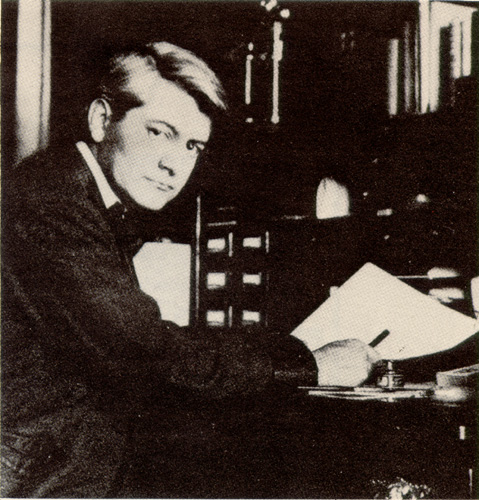

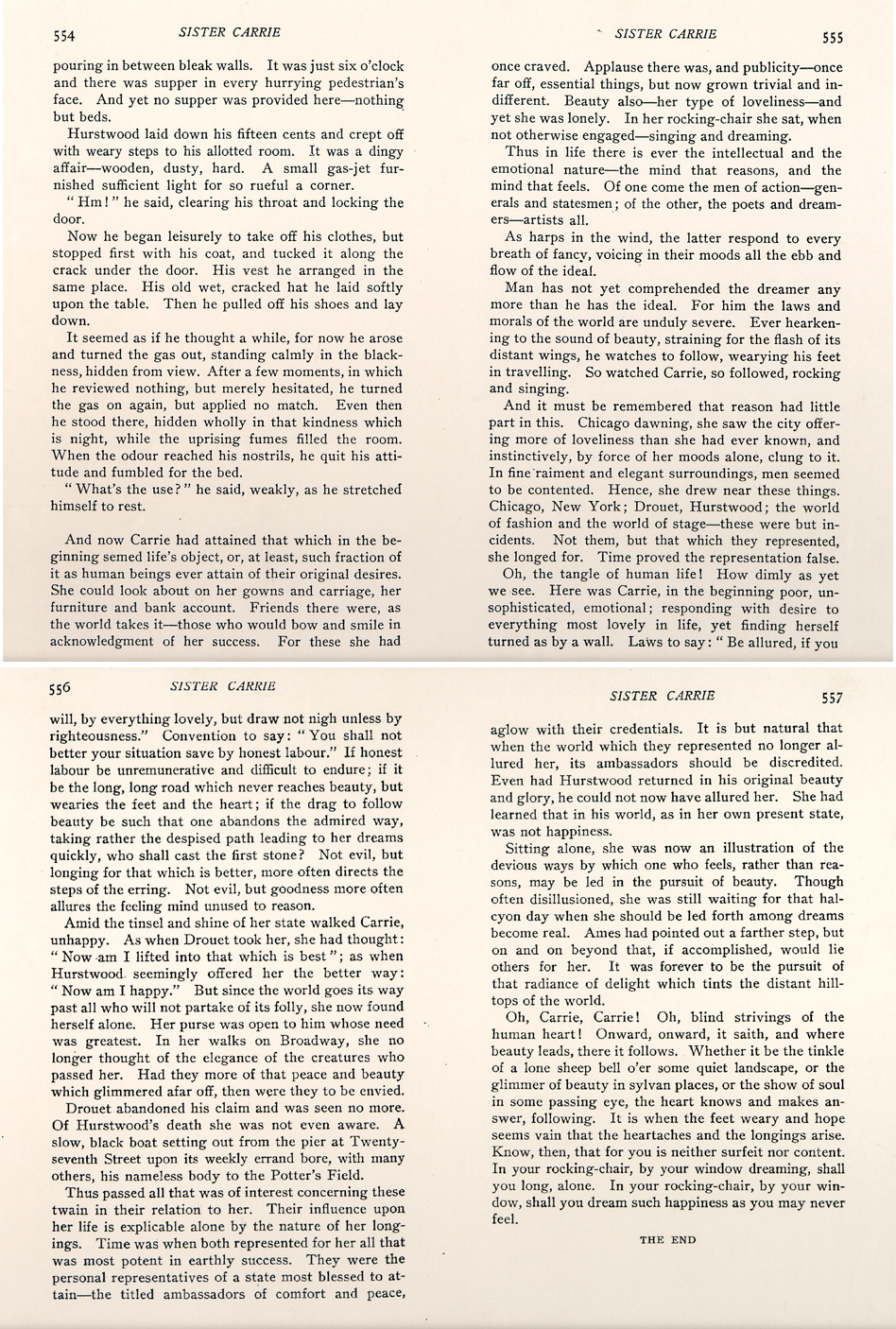

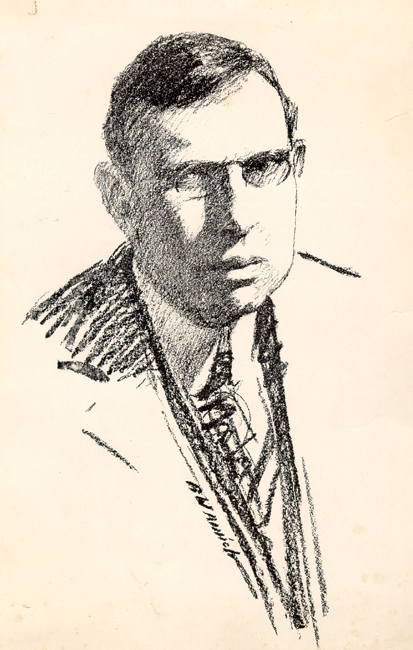

Fig. 1: Taken at the time when Dreiser was shuttling among various city papers from Chicago to St. Louis to Pittsburgh to Toledo

Fig. 2: As editor of Ev'ry Month, Dreiser was able to write a column entitled "Reflections," allowing him to expound on current events. The article for the October 1896 issue contrasts the onerous existence of New York's "have-nots" with the city's opulence as experienced by the "haves." It is signed "THE PROPHET."

Fig. 3: The subject matter for this article at least pertained to an American writer--the Pennsylvania-born poet and novelist Bayard Taylor, who died in 1878.

Fig. 4: From munitions to music, no subject was beyond Dreiser's reach as he sought to make a living as a journalist.

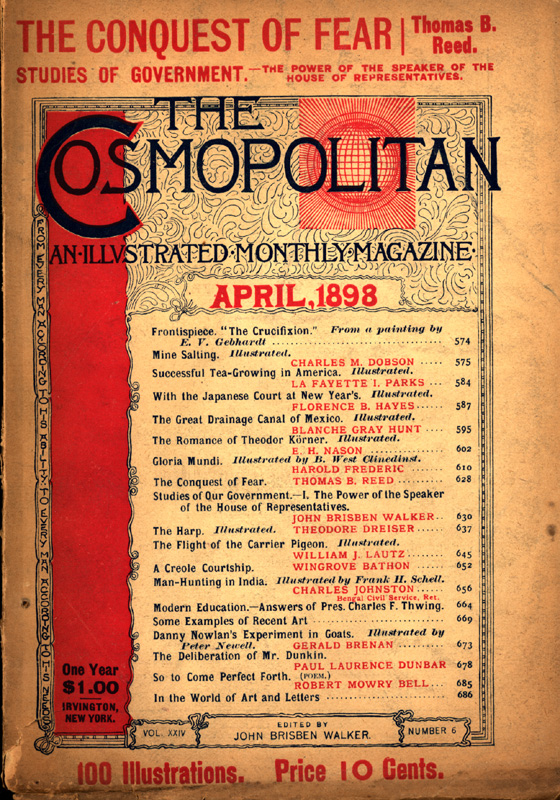

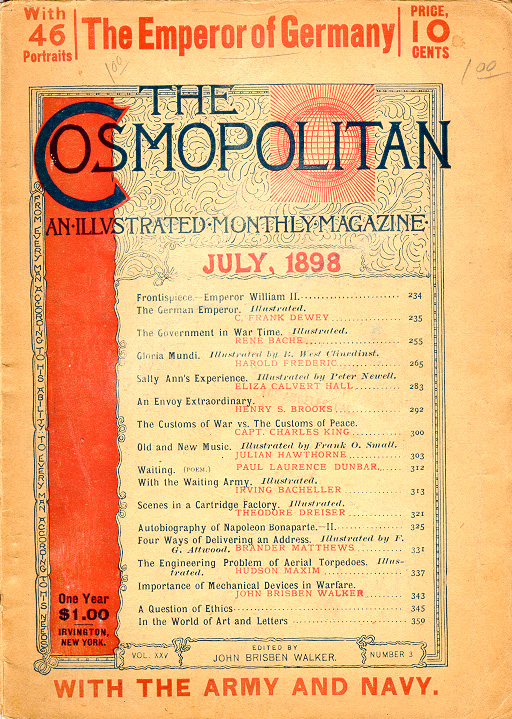

Fig. 5: The illustrated monthly Cosmopolitan published several articles by Dreiser in the late 1890s. This one concerns a munitions factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that produces special cartridges used by the United States Army and Navy in ordinary rifles.

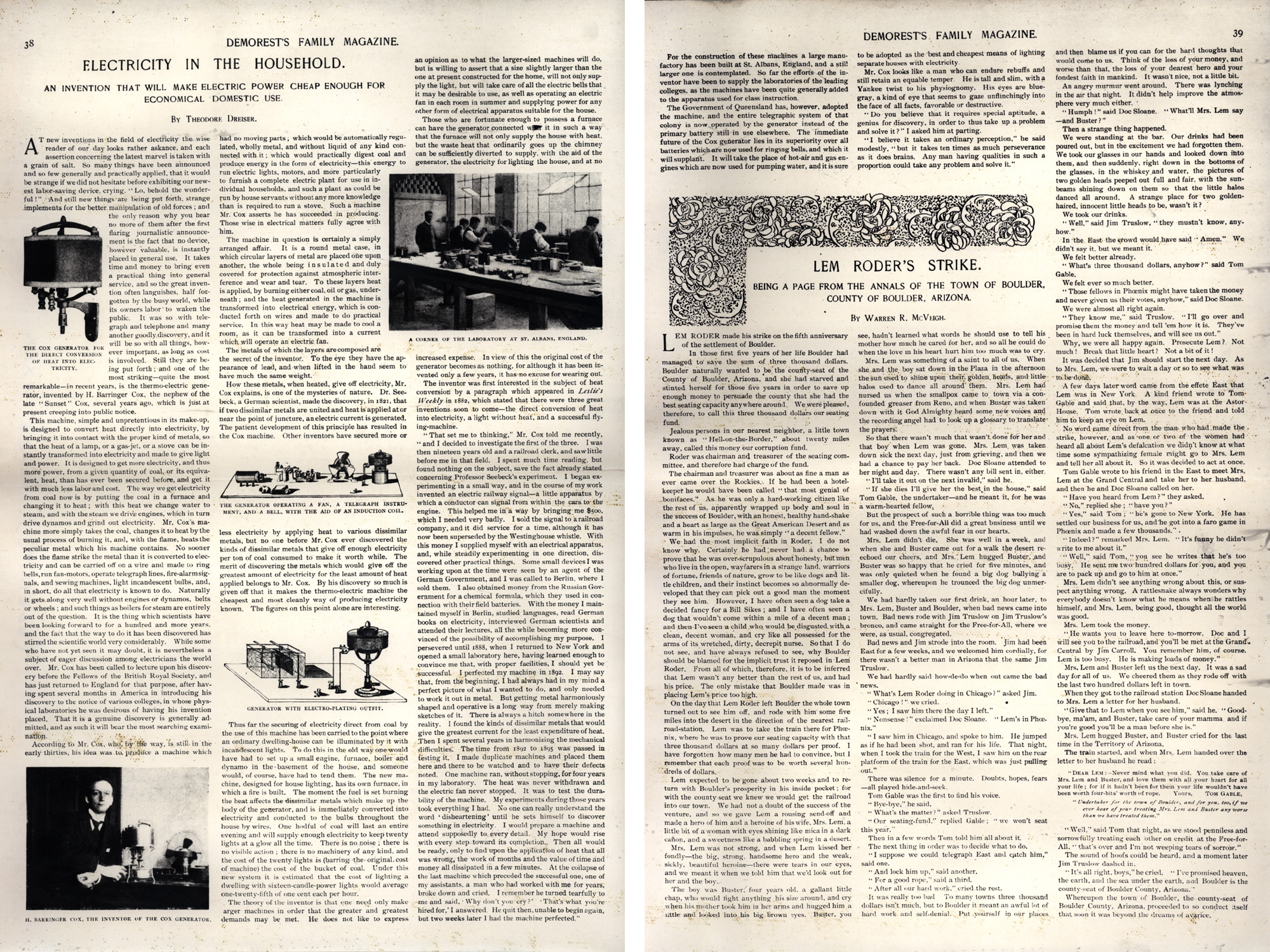

Fig. 6: Photostat of Dreiser's article on the invention of a thermo-electric generator by H. Barringer Cox

Fig. 7: This article reviews the astonishing statistics surrounding the growth of the fruit industry in the United States. Dreiser concludes by praising the resources and potential inherent yet still unfulfilled in America. "For every ray of sunshine used in perfecting bloom and fruitage, ten thousand left to pass! Man shall perfect himself in the wisdom of these things, and there shall no longer be a cry for food."

Before publishing his first novel, Dreiser's apprenticeship in writing comprised a menagerie of short-term assignments and positions with newspapers and magazines from St. Louis to New York. His first reporter's job came in 1892 with the Chicago Daily Globe, considered one of the weakest of the Chicago papers at the time. But the Globe's less-than-premiere status afforded the inexperienced writer the opportunity to prove himself. He parlayed his few months of work at the Chicago Daily Globe into a position at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a morning Republican paper that was the biggest in town. At one point Dreiser was assigned the "hotel beat," which meant interviewing visiting celebrities. After returning to the city room one night, having just interviewed the theosophist Annie Besant, he was called away to cover a triple murder. Still dressed in his rented evening clothes, Dreiser arrived at the scene of the crime to find the bloody corpses of a mother and her two children who had been brutally murdered by her husband, the children's father. This dichotomy between wealth and poverty, between appearance and reality, between prospects and hopelessness informs Sister Carrie.

The life of the newspaperman in Dreiser's time was itself filled with poverty, lasciviousness, and corruption, as were many of the events that a reporter covered. At first naïve, Dreiser quickly learned the ropes and the realities of urban America, but invariably his ideals or vision or personal pride created rifts between himself and management. Freedom--or what appeared to be freedom--to write works to his own plan drove Dreiser not only to seek the editorship at Ev'ry Month but also to pursue creative writing, such as poetry. After departing Ev'ry Monthin September 1897, Dreiser wrote scores of articles for all manner of publications, always hoping that he could find a measure of financial freedom to write his first novel. Among these works came material that would latter be incorporated into Sister Carrie, which he began in earnest in the fall of 1899.

Fig. 1: Taken at the time when Dreiser was shuttling among various city papers from Chicago to St. Louis to Pittsburgh to Toledo

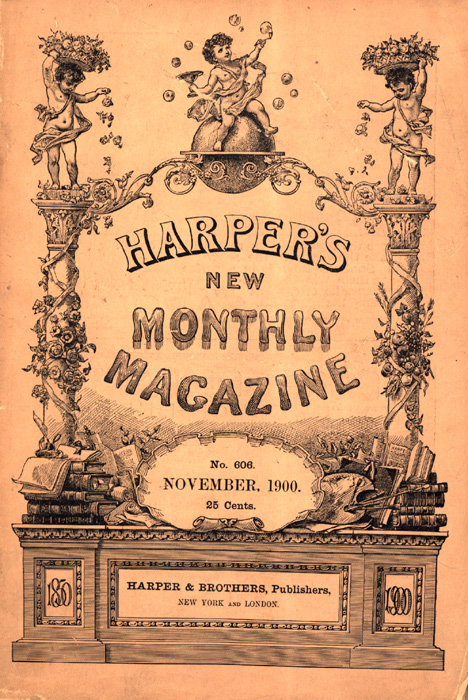

Fig. 2: As editor of Ev'ry Month, Dreiser was able to write a column entitled "Reflections," allowing him to expound on current events. The article for the October 1896 issue contrasts the onerous existence of New York's "have-nots" with the city's opulence as experienced by the "haves." It is signed "THE PROPHET."

Fig. 3: The subject matter for this article at least pertained to an American writer--the Pennsylvania-born poet and novelist Bayard Taylor, who died in 1878.

Fig. 4: From munitions to music, no subject was beyond Dreiser's reach as he sought to make a living as a journalist.

Fig. 5: The illustrated monthly Cosmopolitan published several articles by Dreiser in the late 1890s. This one concerns a munitions factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that produces special cartridges used by the United States Army and Navy in ordinary rifles.

Fig. 6: Photostat of Dreiser's article on the invention of a thermo-electric generator by H. Barringer Cox

Fig. 7: This article reviews the astonishing statistics surrounding the growth of the fruit industry in the United States. Dreiser concludes by praising the resources and potential inherent yet still unfulfilled in America. "For every ray of sunshine used in perfecting bloom and fruitage, ten thousand left to pass! Man shall perfect himself in the wisdom of these things, and there shall no longer be a cry for food."

Before publishing his first novel, Dreiser's apprenticeship in writing comprised a menagerie of short-term assignments and positions with newspapers and magazines from St. Louis to New York. His first reporter's job came in 1892 with the Chicago Daily Globe, considered one of the weakest of the Chicago papers at the time. But the Globe's less-than-premiere status afforded the inexperienced writer the opportunity to prove himself. He parlayed his few months of work at the Chicago Daily Globe into a position at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a morning Republican paper that was the biggest in town. At one point Dreiser was assigned the "hotel beat," which meant interviewing visiting celebrities. After returning to the city room one night, having just interviewed the theosophist Annie Besant, he was called away to cover a triple murder. Still dressed in his rented evening clothes, Dreiser arrived at the scene of the crime to find the bloody corpses of a mother and her two children who had been brutally murdered by her husband, the children's father. This dichotomy between wealth and poverty, between appearance and reality, between prospects and hopelessness informs Sister Carrie.

The life of the newspaperman in Dreiser's time was itself filled with poverty, lasciviousness, and corruption, as were many of the events that a reporter covered. At first naïve, Dreiser quickly learned the ropes and the realities of urban America, but invariably his ideals or vision or personal pride created rifts between himself and management. Freedom--or what appeared to be freedom--to write works to his own plan drove Dreiser not only to seek the editorship at Ev'ry Month but also to pursue creative writing, such as poetry. After departing Ev'ry Monthin September 1897, Dreiser wrote scores of articles for all manner of publications, always hoping that he could find a measure of financial freedom to write his first novel. Among these works came material that would latter be incorporated into Sister Carrie, which he began in earnest in the fall of 1899.

Fig. 1: Taken at the time when Dreiser was shuttling among various city papers from Chicago to St. Louis to Pittsburgh to Toledo

Fig. 2: As editor of Ev'ry Month, Dreiser was able to write a column entitled "Reflections," allowing him to expound on current events. The article for the October 1896 issue contrasts the onerous existence of New York's "have-nots" with the city's opulence as experienced by the "haves." It is signed "THE PROPHET."

Fig. 3: The subject matter for this article at least pertained to an American writer--the Pennsylvania-born poet and novelist Bayard Taylor, who died in 1878.

Fig. 4: From munitions to music, no subject was beyond Dreiser's reach as he sought to make a living as a journalist.

Fig. 5: The illustrated monthly Cosmopolitan published several articles by Dreiser in the late 1890s. This one concerns a munitions factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that produces special cartridges used by the United States Army and Navy in ordinary rifles.

Fig. 6: Photostat of Dreiser's article on the invention of a thermo-electric generator by H. Barringer Cox

Fig. 7: This article reviews the astonishing statistics surrounding the growth of the fruit industry in the United States. Dreiser concludes by praising the resources and potential inherent yet still unfulfilled in America. "For every ray of sunshine used in perfecting bloom and fruitage, ten thousand left to pass! Man shall perfect himself in the wisdom of these things, and there shall no longer be a cry for food."

Before publishing his first novel, Dreiser's apprenticeship in writing comprised a menagerie of short-term assignments and positions with newspapers and magazines from St. Louis to New York. His first reporter's job came in 1892 with the Chicago Daily Globe, considered one of the weakest of the Chicago papers at the time. But the Globe's less-than-premiere status afforded the inexperienced writer the opportunity to prove himself. He parlayed his few months of work at the Chicago Daily Globe into a position at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a morning Republican paper that was the biggest in town. At one point Dreiser was assigned the "hotel beat," which meant interviewing visiting celebrities. After returning to the city room one night, having just interviewed the theosophist Annie Besant, he was called away to cover a triple murder. Still dressed in his rented evening clothes, Dreiser arrived at the scene of the crime to find the bloody corpses of a mother and her two children who had been brutally murdered by her husband, the children's father. This dichotomy between wealth and poverty, between appearance and reality, between prospects and hopelessness informs Sister Carrie.

The life of the newspaperman in Dreiser's time was itself filled with poverty, lasciviousness, and corruption, as were many of the events that a reporter covered. At first naïve, Dreiser quickly learned the ropes and the realities of urban America, but invariably his ideals or vision or personal pride created rifts between himself and management. Freedom--or what appeared to be freedom--to write works to his own plan drove Dreiser not only to seek the editorship at Ev'ry Month but also to pursue creative writing, such as poetry. After departing Ev'ry Monthin September 1897, Dreiser wrote scores of articles for all manner of publications, always hoping that he could find a measure of financial freedom to write his first novel. Among these works came material that would latter be incorporated into Sister Carrie, which he began in earnest in the fall of 1899.

Fig. 1: Taken at the time when Dreiser was shuttling among various city papers from Chicago to St. Louis to Pittsburgh to Toledo

Fig. 2: As editor of Ev'ry Month, Dreiser was able to write a column entitled "Reflections," allowing him to expound on current events. The article for the October 1896 issue contrasts the onerous existence of New York's "have-nots" with the city's opulence as experienced by the "haves." It is signed "THE PROPHET."

Fig. 3: The subject matter for this article at least pertained to an American writer--the Pennsylvania-born poet and novelist Bayard Taylor, who died in 1878.

Fig. 4: From munitions to music, no subject was beyond Dreiser's reach as he sought to make a living as a journalist.

Fig. 5: The illustrated monthly Cosmopolitan published several articles by Dreiser in the late 1890s. This one concerns a munitions factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that produces special cartridges used by the United States Army and Navy in ordinary rifles.

Fig. 6: Photostat of Dreiser's article on the invention of a thermo-electric generator by H. Barringer Cox

Fig. 7: This article reviews the astonishing statistics surrounding the growth of the fruit industry in the United States. Dreiser concludes by praising the resources and potential inherent yet still unfulfilled in America. "For every ray of sunshine used in perfecting bloom and fruitage, ten thousand left to pass! Man shall perfect himself in the wisdom of these things, and there shall no longer be a cry for food."

Before publishing his first novel, Dreiser's apprenticeship in writing comprised a menagerie of short-term assignments and positions with newspapers and magazines from St. Louis to New York. His first reporter's job came in 1892 with the Chicago Daily Globe, considered one of the weakest of the Chicago papers at the time. But the Globe's less-than-premiere status afforded the inexperienced writer the opportunity to prove himself. He parlayed his few months of work at the Chicago Daily Globe into a position at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a morning Republican paper that was the biggest in town. At one point Dreiser was assigned the "hotel beat," which meant interviewing visiting celebrities. After returning to the city room one night, having just interviewed the theosophist Annie Besant, he was called away to cover a triple murder. Still dressed in his rented evening clothes, Dreiser arrived at the scene of the crime to find the bloody corpses of a mother and her two children who had been brutally murdered by her husband, the children's father. This dichotomy between wealth and poverty, between appearance and reality, between prospects and hopelessness informs Sister Carrie.

The life of the newspaperman in Dreiser's time was itself filled with poverty, lasciviousness, and corruption, as were many of the events that a reporter covered. At first naïve, Dreiser quickly learned the ropes and the realities of urban America, but invariably his ideals or vision or personal pride created rifts between himself and management. Freedom--or what appeared to be freedom--to write works to his own plan drove Dreiser not only to seek the editorship at Ev'ry Month but also to pursue creative writing, such as poetry. After departing Ev'ry Monthin September 1897, Dreiser wrote scores of articles for all manner of publications, always hoping that he could find a measure of financial freedom to write his first novel. Among these works came material that would latter be incorporated into Sister Carrie, which he began in earnest in the fall of 1899.

Fig. 1: Taken at the time when Dreiser was shuttling among various city papers from Chicago to St. Louis to Pittsburgh to Toledo

Fig. 2: As editor of Ev'ry Month, Dreiser was able to write a column entitled "Reflections," allowing him to expound on current events. The article for the October 1896 issue contrasts the onerous existence of New York's "have-nots" with the city's opulence as experienced by the "haves." It is signed "THE PROPHET."

Fig. 3: The subject matter for this article at least pertained to an American writer--the Pennsylvania-born poet and novelist Bayard Taylor, who died in 1878.

Fig. 4: From munitions to music, no subject was beyond Dreiser's reach as he sought to make a living as a journalist.

Fig. 5: The illustrated monthly Cosmopolitan published several articles by Dreiser in the late 1890s. This one concerns a munitions factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that produces special cartridges used by the United States Army and Navy in ordinary rifles.

Fig. 6: Photostat of Dreiser's article on the invention of a thermo-electric generator by H. Barringer Cox

Fig. 7: This article reviews the astonishing statistics surrounding the growth of the fruit industry in the United States. Dreiser concludes by praising the resources and potential inherent yet still unfulfilled in America. "For every ray of sunshine used in perfecting bloom and fruitage, ten thousand left to pass! Man shall perfect himself in the wisdom of these things, and there shall no longer be a cry for food."

Before publishing his first novel, Dreiser's apprenticeship in writing comprised a menagerie of short-term assignments and positions with newspapers and magazines from St. Louis to New York. His first reporter's job came in 1892 with the Chicago Daily Globe, considered one of the weakest of the Chicago papers at the time. But the Globe's less-than-premiere status afforded the inexperienced writer the opportunity to prove himself. He parlayed his few months of work at the Chicago Daily Globe into a position at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a morning Republican paper that was the biggest in town. At one point Dreiser was assigned the "hotel beat," which meant interviewing visiting celebrities. After returning to the city room one night, having just interviewed the theosophist Annie Besant, he was called away to cover a triple murder. Still dressed in his rented evening clothes, Dreiser arrived at the scene of the crime to find the bloody corpses of a mother and her two children who had been brutally murdered by her husband, the children's father. This dichotomy between wealth and poverty, between appearance and reality, between prospects and hopelessness informs Sister Carrie.

The life of the newspaperman in Dreiser's time was itself filled with poverty, lasciviousness, and corruption, as were many of the events that a reporter covered. At first naïve, Dreiser quickly learned the ropes and the realities of urban America, but invariably his ideals or vision or personal pride created rifts between himself and management. Freedom--or what appeared to be freedom--to write works to his own plan drove Dreiser not only to seek the editorship at Ev'ry Month but also to pursue creative writing, such as poetry. After departing Ev'ry Monthin September 1897, Dreiser wrote scores of articles for all manner of publications, always hoping that he could find a measure of financial freedom to write his first novel. Among these works came material that would latter be incorporated into Sister Carrie, which he began in earnest in the fall of 1899.

Fig. 1: Taken at the time when Dreiser was shuttling among various city papers from Chicago to St. Louis to Pittsburgh to Toledo

Fig. 2: As editor of Ev'ry Month, Dreiser was able to write a column entitled "Reflections," allowing him to expound on current events. The article for the October 1896 issue contrasts the onerous existence of New York's "have-nots" with the city's opulence as experienced by the "haves." It is signed "THE PROPHET."

Fig. 3: The subject matter for this article at least pertained to an American writer--the Pennsylvania-born poet and novelist Bayard Taylor, who died in 1878.

Fig. 4: From munitions to music, no subject was beyond Dreiser's reach as he sought to make a living as a journalist.

Fig. 5: The illustrated monthly Cosmopolitan published several articles by Dreiser in the late 1890s. This one concerns a munitions factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that produces special cartridges used by the United States Army and Navy in ordinary rifles.

Fig. 6: Photostat of Dreiser's article on the invention of a thermo-electric generator by H. Barringer Cox

Fig. 7: This article reviews the astonishing statistics surrounding the growth of the fruit industry in the United States. Dreiser concludes by praising the resources and potential inherent yet still unfulfilled in America. "For every ray of sunshine used in perfecting bloom and fruitage, ten thousand left to pass! Man shall perfect himself in the wisdom of these things, and there shall no longer be a cry for food."

Before publishing his first novel, Dreiser's apprenticeship in writing comprised a menagerie of short-term assignments and positions with newspapers and magazines from St. Louis to New York. His first reporter's job came in 1892 with the Chicago Daily Globe, considered one of the weakest of the Chicago papers at the time. But the Globe's less-than-premiere status afforded the inexperienced writer the opportunity to prove himself. He parlayed his few months of work at the Chicago Daily Globe into a position at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a morning Republican paper that was the biggest in town. At one point Dreiser was assigned the "hotel beat," which meant interviewing visiting celebrities. After returning to the city room one night, having just interviewed the theosophist Annie Besant, he was called away to cover a triple murder. Still dressed in his rented evening clothes, Dreiser arrived at the scene of the crime to find the bloody corpses of a mother and her two children who had been brutally murdered by her husband, the children's father. This dichotomy between wealth and poverty, between appearance and reality, between prospects and hopelessness informs Sister Carrie.

The life of the newspaperman in Dreiser's time was itself filled with poverty, lasciviousness, and corruption, as were many of the events that a reporter covered. At first naïve, Dreiser quickly learned the ropes and the realities of urban America, but invariably his ideals or vision or personal pride created rifts between himself and management. Freedom--or what appeared to be freedom--to write works to his own plan drove Dreiser not only to seek the editorship at Ev'ry Month but also to pursue creative writing, such as poetry. After departing Ev'ry Monthin September 1897, Dreiser wrote scores of articles for all manner of publications, always hoping that he could find a measure of financial freedom to write his first novel. Among these works came material that would latter be incorporated into Sister Carrie, which he began in earnest in the fall of 1899.

Fig. 1: Taken at the time when Dreiser was shuttling among various city papers from Chicago to St. Louis to Pittsburgh to Toledo

Fig. 2: As editor of Ev'ry Month, Dreiser was able to write a column entitled "Reflections," allowing him to expound on current events. The article for the October 1896 issue contrasts the onerous existence of New York's "have-nots" with the city's opulence as experienced by the "haves." It is signed "THE PROPHET."

Fig. 3: The subject matter for this article at least pertained to an American writer--the Pennsylvania-born poet and novelist Bayard Taylor, who died in 1878.

Fig. 4: From munitions to music, no subject was beyond Dreiser's reach as he sought to make a living as a journalist.

Fig. 5: The illustrated monthly Cosmopolitan published several articles by Dreiser in the late 1890s. This one concerns a munitions factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that produces special cartridges used by the United States Army and Navy in ordinary rifles.

Fig. 6: Photostat of Dreiser's article on the invention of a thermo-electric generator by H. Barringer Cox

Fig. 7: This article reviews the astonishing statistics surrounding the growth of the fruit industry in the United States. Dreiser concludes by praising the resources and potential inherent yet still unfulfilled in America. "For every ray of sunshine used in perfecting bloom and fruitage, ten thousand left to pass! Man shall perfect himself in the wisdom of these things, and there shall no longer be a cry for food."

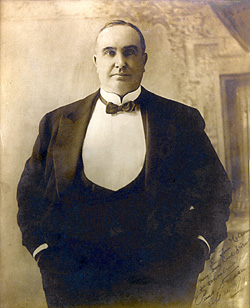

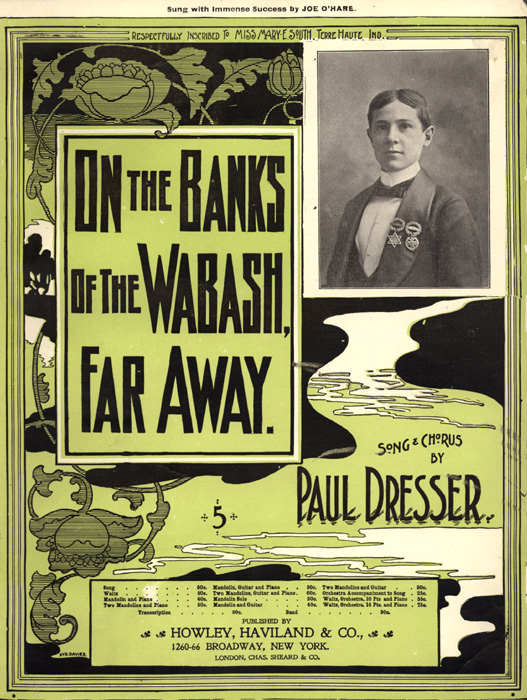

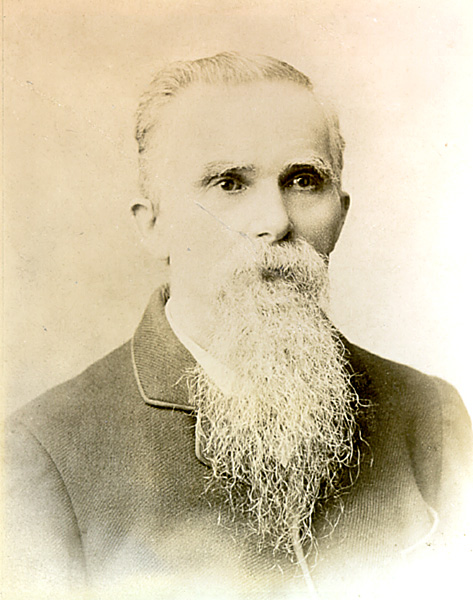

Born in 1857, John Paul Dreiser, Jr., eldest son of John Paul and Sarah Dreiser, was quick to flee the family, in particular, his stern father and the conventionality of small-town America. High-spirited and mischievous, Paul Dresser--the professional name that he adopted--was musically gifted. As a composer of popular songs, he enjoyed--at times--enormous financial success. In 1895 and in 1897, for example, he published his two biggest-selling hits, " Just Tell Them That You Saw Me" and "On the Banks of the Wabash," yielding for Paul an income of $80,000 (each title sold over a half million copies). Paul frequently came to the financial rescue of his family, and his connections with music publishers Howley-Haviland & Co. gave Dreiser the entree to propose a new journal--with him as editor--entitled Ev'ry Month, a large format magazine comprising four songs per issue and an array of fiction, poetry, interviews, book reviews, photographs, and advice for women.

The influences of Paul Dresser are manifold in Sister Carrie. Upon arriving in Chicago, Carrie is immediately drawn to the excitement and gaiety of popular entertainment. The theatrical world becomes her means to improve her financial life and free herself not only from the dreariness of working-class employment typical for young women of her background but also from the dependency on male companions to underwrite her room and board. Dreiser had an intimate view of this world through his brother Paul. In addition, many scholars have noted that the characters Charlie Drouet and George Hurstwood resemble Paul Dresser--not in terms of occupation but in terms of personality: tremendously affable but shallow, ultimately weak regarding their vanity and sensual appetites. On 30 January 1906 Paul Dresser, forty-eight years old, died of a heart attack at the home of his sister Emma; he was financially destitute and had been abandoned by most of his friends.

Fig. 2: Inscription: "For Tom Nelson my boyhood friend & schoolmate. Paul Dresser, Sept. 14th/1901"

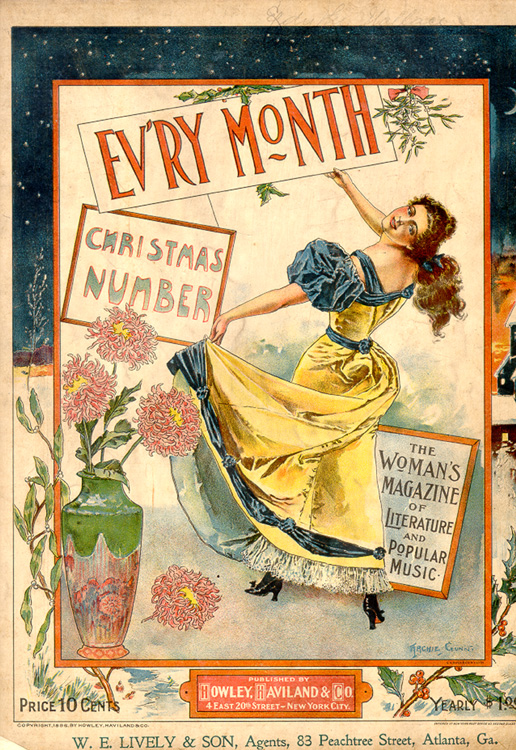

Fig. 3: Combining as it did both music and written articles and stories, this publishing venture briefly united brothers Paul and Ted professionally. The first issue of Ev'ry Month was published in October 1895, but the September 1897 issue was Dreiser's last. The freedom of expression and selection that he thought was now his as conceiver and editor of Ev'ry Month proved hollow. Dreiser quarreled with his brother and demanded more money and editorial license from the publisher Howley, and they parted company.

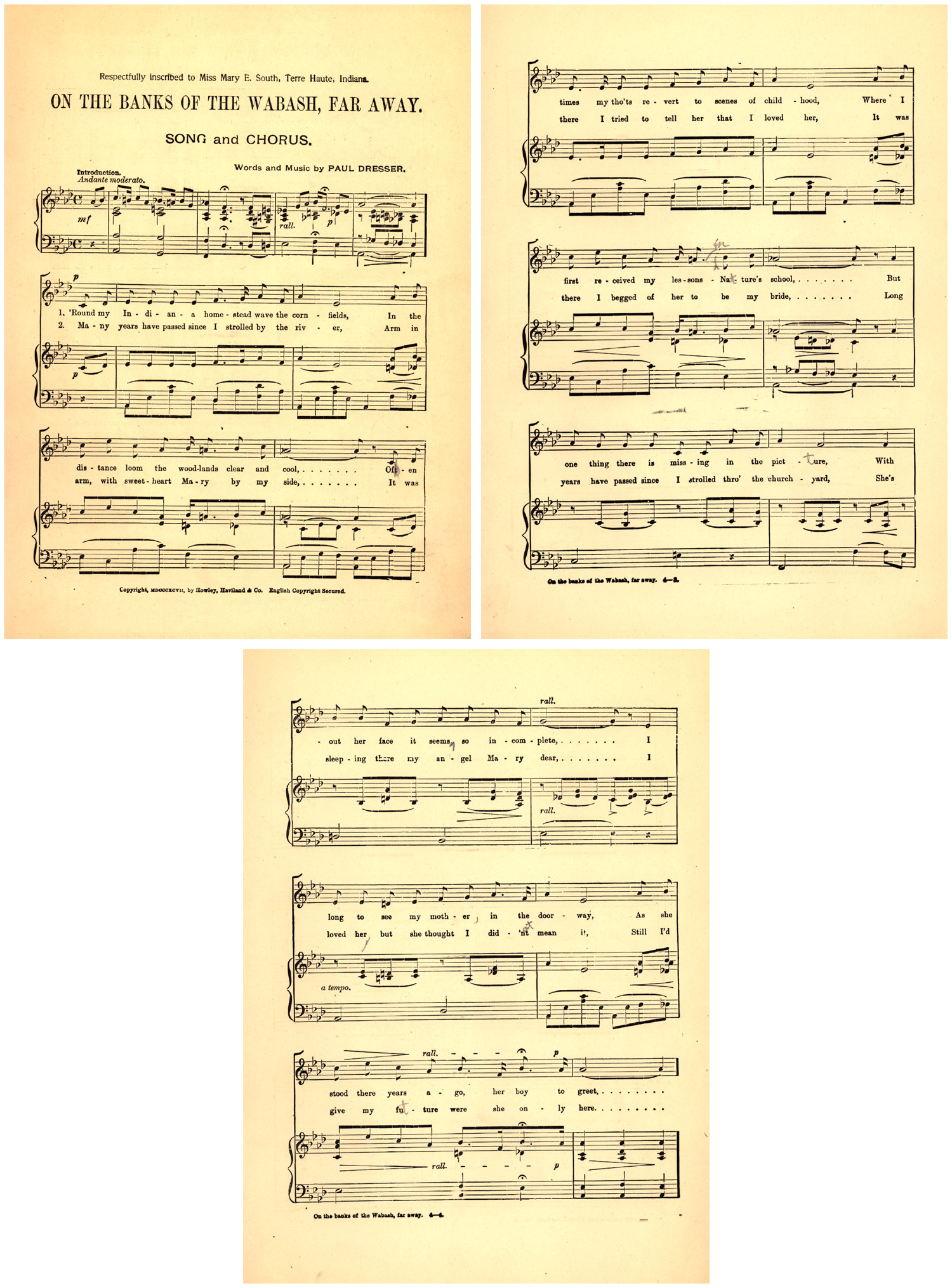

Fig. 4 - Fig. 5: In 1897 Ted was with his brother Paul in the offices of Howley, Haviland & Co. While improvising on the piano, Paul urged Ted for a idea for a song. The resulting conversation led to "On the Banks of the Wabash"; Ted, in fact, wrote the first verse and chorus. In 1913 the State Assembly of Indiana adopted "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away" as the official state song.

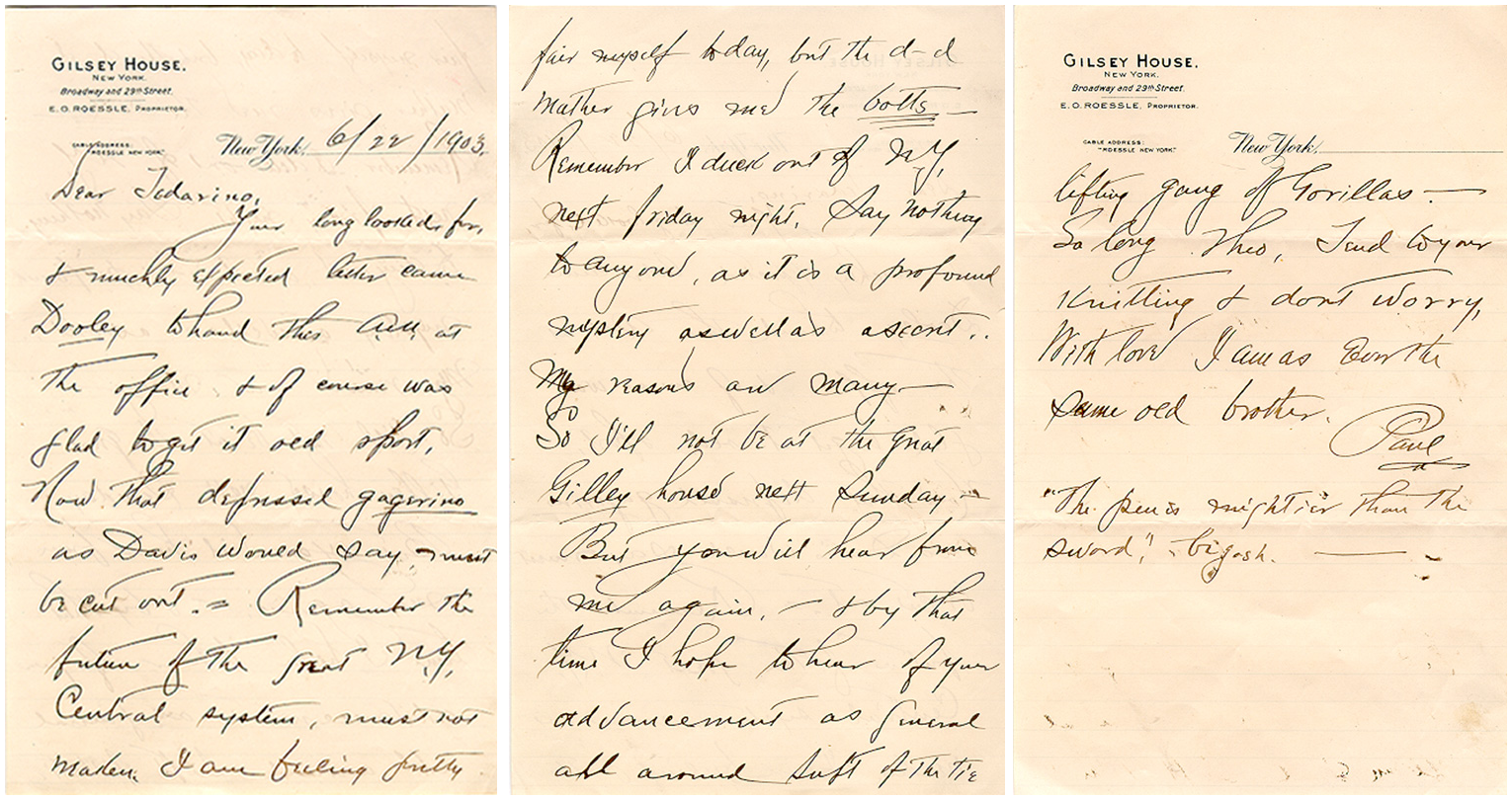

Fig. 6: Beginning with "Dear Tedarino" and closing with "I am as ever the same old brother," this letter conveys the loyalty, camaraderie, and high spirits of Dreiser's eldest brother. Paul cautions Ted not to worry, claiming in his postscript that "The pen is mightier than the sword.' bigosh." This was at a particularly low time for Dreiser, who was suffering a nervous breakdown as a result of the suppression of Sister Carrie. Per usual, Paul shared his financial resources with his family, while also respecting Ted's pride by stating that he owed Dreiser royalties for "On the Banks of the Wabash."

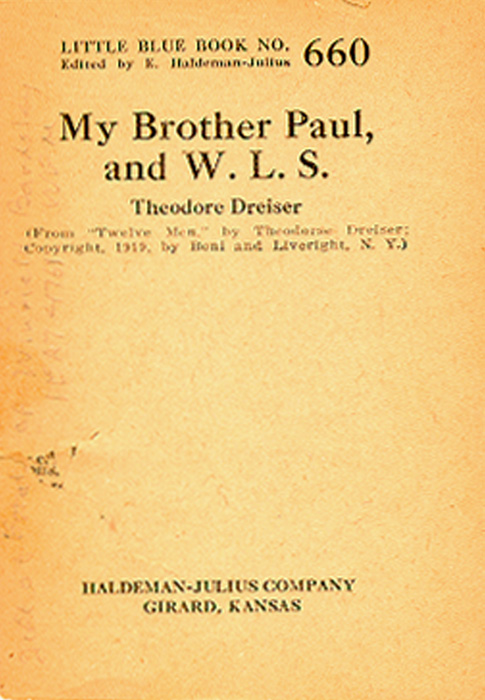

Fig. 7: In 1919 Boni & Liveright published Dreiser's Twelve Men, personality sketches that illustrated the author's notion that goodness can be found in unconventional lives. Some of the essays were reworked material written as early as 1902, but "My Brother Paul" was a new piece that afforded Dreiser the opportunity to remember fondly the tender-hearted man whom he characterized as "generous to the point of self-destruction." Although reviews were generally favorable for Twelve Men, sales stagnated, with less than 2,000 copies sold in the first year. In 1924 publishers Haldeman-Julius reprinted two of the portraits from Twelve Men as Little Blue Book No. 660.

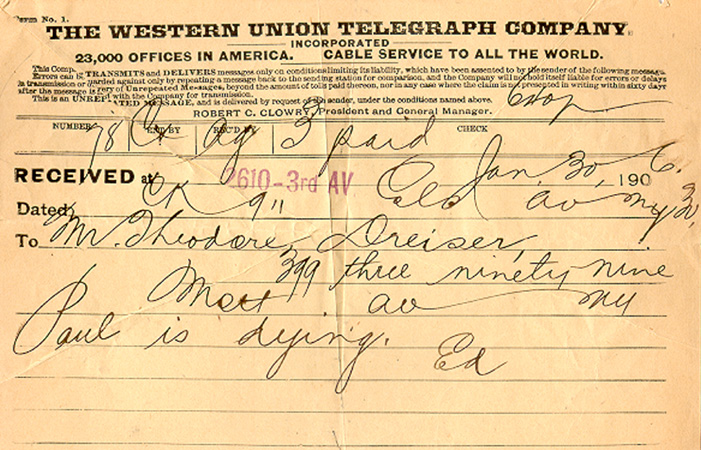

Fig. 8: Dreiser was summoned by his brother Ed to their sister Emma's apartment in New York on 30 January 1906, the night that Paul Dresser died.

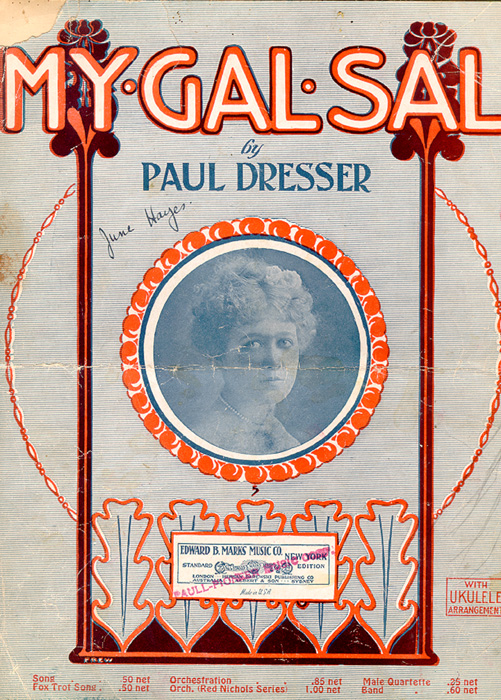

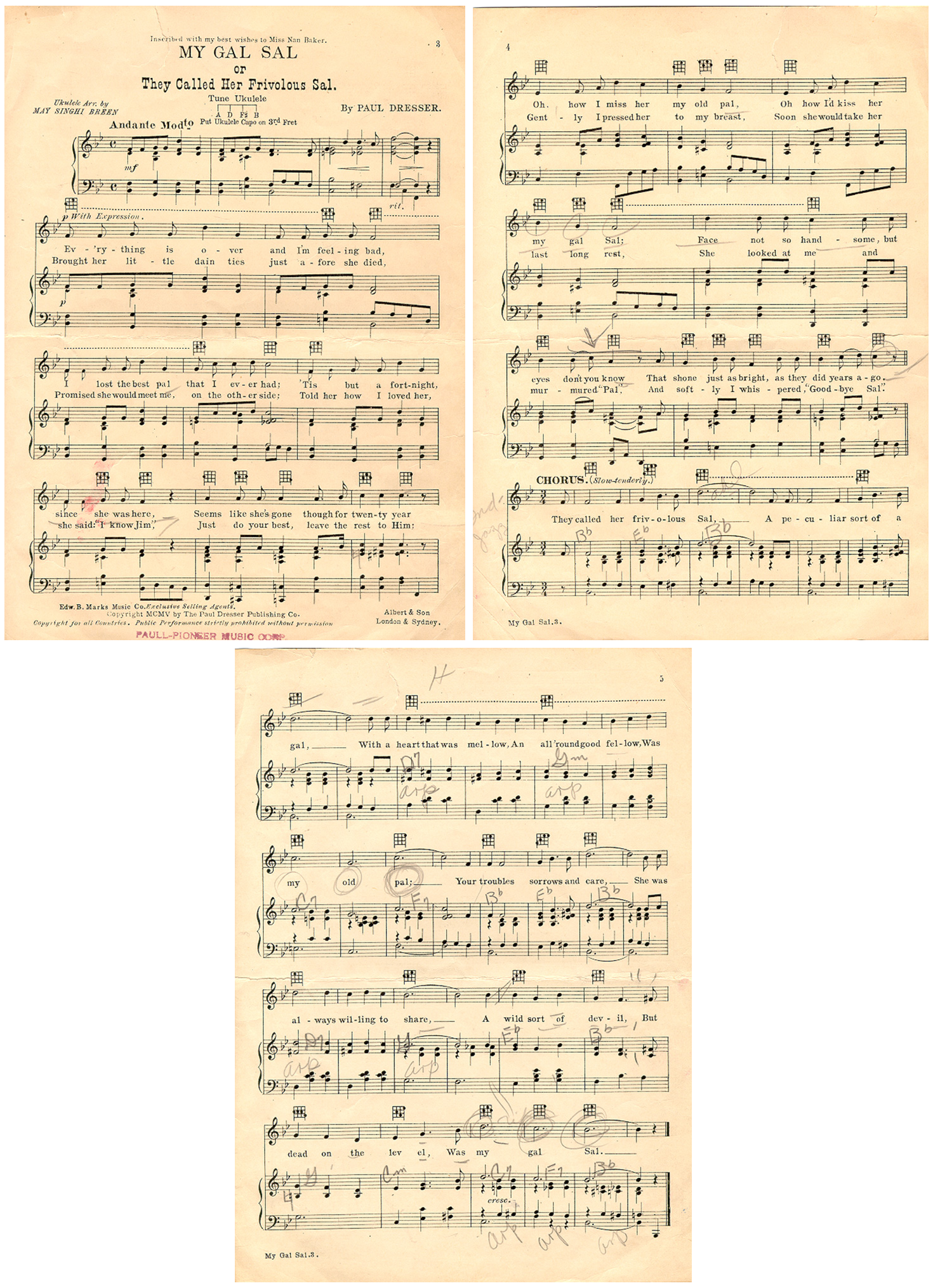

Fig. 9 - Fig. 10: he first page of the sheet music, whose title became the focus of the 1942 motion picture about the life and career of Paul Dresser, imparts a sentimental lyric set to ukulele music. Sal was, in fact, Sallie Walker, Paul's former mistress, who operated a highly successful house of prostitution on Main Street in Evansville, Illinois. It was a combination of Paul's success as a composer and Sallie's success as a madam that allowed Paul to move his then-destitute mother into a small home in Evansville in the early 1880s

Fig. 11 - Fig. 12: After decades of false starts and tangled negotiations, a cinematic version of Paul Dresser's life story was finally produced by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1942. The Hollywood musical starred Victor Mature as Dresser and Rita Hayworth as Sally (Sal) Elliot; it was loosely based on Dreiser's essay "My Brother Paul" and included many of Dresser's songs. The rights for the movie and for the songs were sold for between $35,000 and $50,000, and the proceeds were divided among Dresser's surviving siblings (Theodore, Ed, Mame, and Sylvia).

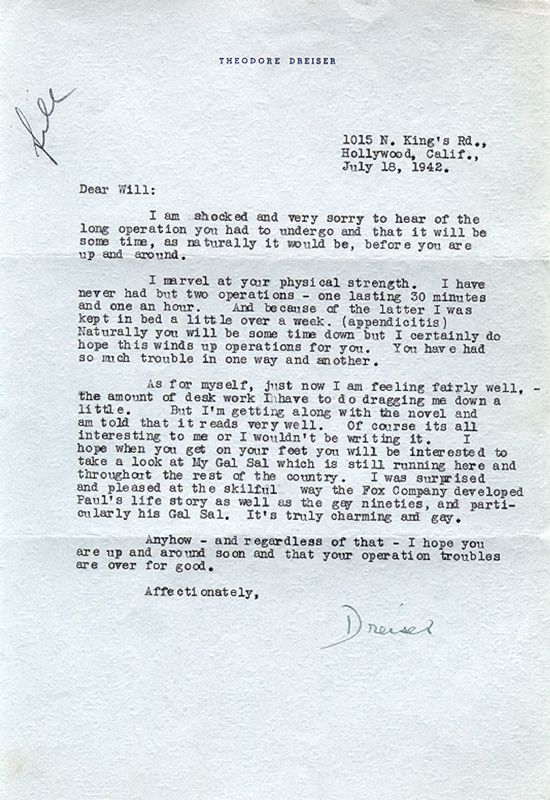

Fig. 13: In this letter to his former secretary, sometimes literary agent, and loyal friend and supporter, Dreiser urges Lengel to see My Gal Sal and offers his reaction to the Hollywood biography--so long in the making--of his brother Paul.

"I was surprised and pleased at the skilful way the Fox Company developed Paul's life story as well as the gay nineties, and particularly his Gal Sal. It's truly charming and gay."

Born in 1857, John Paul Dreiser, Jr., eldest son of John Paul and Sarah Dreiser, was quick to flee the family, in particular, his stern father and the conventionality of small-town America. High-spirited and mischievous, Paul Dresser--the professional name that he adopted--was musically gifted. As a composer of popular songs, he enjoyed--at times--enormous financial success. In 1895 and in 1897, for example, he published his two biggest-selling hits, " Just Tell Them That You Saw Me" and "On the Banks of the Wabash," yielding for Paul an income of $80,000 (each title sold over a half million copies). Paul frequently came to the financial rescue of his family, and his connections with music publishers Howley-Haviland & Co. gave Dreiser the entree to propose a new journal--with him as editor--entitled Ev'ry Month, a large format magazine comprising four songs per issue and an array of fiction, poetry, interviews, book reviews, photographs, and advice for women.

The influences of Paul Dresser are manifold in Sister Carrie. Upon arriving in Chicago, Carrie is immediately drawn to the excitement and gaiety of popular entertainment. The theatrical world becomes her means to improve her financial life and free herself not only from the dreariness of working-class employment typical for young women of her background but also from the dependency on male companions to underwrite her room and board. Dreiser had an intimate view of this world through his brother Paul. In addition, many scholars have noted that the characters Charlie Drouet and George Hurstwood resemble Paul Dresser--not in terms of occupation but in terms of personality: tremendously affable but shallow, ultimately weak regarding their vanity and sensual appetites. On 30 January 1906 Paul Dresser, forty-eight years old, died of a heart attack at the home of his sister Emma; he was financially destitute and had been abandoned by most of his friends.

Fig. 2: Inscription: "For Tom Nelson my boyhood friend & schoolmate. Paul Dresser, Sept. 14th/1901"

Fig. 3: Combining as it did both music and written articles and stories, this publishing venture briefly united brothers Paul and Ted professionally. The first issue of Ev'ry Month was published in October 1895, but the September 1897 issue was Dreiser's last. The freedom of expression and selection that he thought was now his as conceiver and editor of Ev'ry Month proved hollow. Dreiser quarreled with his brother and demanded more money and editorial license from the publisher Howley, and they parted company.

Fig. 4 - Fig. 5: In 1897 Ted was with his brother Paul in the offices of Howley, Haviland & Co. While improvising on the piano, Paul urged Ted for a idea for a song. The resulting conversation led to "On the Banks of the Wabash"; Ted, in fact, wrote the first verse and chorus. In 1913 the State Assembly of Indiana adopted "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away" as the official state song.

Fig. 6: Beginning with "Dear Tedarino" and closing with "I am as ever the same old brother," this letter conveys the loyalty, camaraderie, and high spirits of Dreiser's eldest brother. Paul cautions Ted not to worry, claiming in his postscript that "The pen is mightier than the sword.' bigosh." This was at a particularly low time for Dreiser, who was suffering a nervous breakdown as a result of the suppression of Sister Carrie. Per usual, Paul shared his financial resources with his family, while also respecting Ted's pride by stating that he owed Dreiser royalties for "On the Banks of the Wabash."

Fig. 7: In 1919 Boni & Liveright published Dreiser's Twelve Men, personality sketches that illustrated the author's notion that goodness can be found in unconventional lives. Some of the essays were reworked material written as early as 1902, but "My Brother Paul" was a new piece that afforded Dreiser the opportunity to remember fondly the tender-hearted man whom he characterized as "generous to the point of self-destruction." Although reviews were generally favorable for Twelve Men, sales stagnated, with less than 2,000 copies sold in the first year. In 1924 publishers Haldeman-Julius reprinted two of the portraits from Twelve Men as Little Blue Book No. 660.

Fig. 8: Dreiser was summoned by his brother Ed to their sister Emma's apartment in New York on 30 January 1906, the night that Paul Dresser died.

Fig. 9 - Fig. 10: he first page of the sheet music, whose title became the focus of the 1942 motion picture about the life and career of Paul Dresser, imparts a sentimental lyric set to ukulele music. Sal was, in fact, Sallie Walker, Paul's former mistress, who operated a highly successful house of prostitution on Main Street in Evansville, Illinois. It was a combination of Paul's success as a composer and Sallie's success as a madam that allowed Paul to move his then-destitute mother into a small home in Evansville in the early 1880s

Fig. 11 - Fig. 12: After decades of false starts and tangled negotiations, a cinematic version of Paul Dresser's life story was finally produced by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1942. The Hollywood musical starred Victor Mature as Dresser and Rita Hayworth as Sally (Sal) Elliot; it was loosely based on Dreiser's essay "My Brother Paul" and included many of Dresser's songs. The rights for the movie and for the songs were sold for between $35,000 and $50,000, and the proceeds were divided among Dresser's surviving siblings (Theodore, Ed, Mame, and Sylvia).

Fig. 13: In this letter to his former secretary, sometimes literary agent, and loyal friend and supporter, Dreiser urges Lengel to see My Gal Sal and offers his reaction to the Hollywood biography--so long in the making--of his brother Paul.

"I was surprised and pleased at the skilful way the Fox Company developed Paul's life story as well as the gay nineties, and particularly his Gal Sal. It's truly charming and gay."

Born in 1857, John Paul Dreiser, Jr., eldest son of John Paul and Sarah Dreiser, was quick to flee the family, in particular, his stern father and the conventionality of small-town America. High-spirited and mischievous, Paul Dresser--the professional name that he adopted--was musically gifted. As a composer of popular songs, he enjoyed--at times--enormous financial success. In 1895 and in 1897, for example, he published his two biggest-selling hits, " Just Tell Them That You Saw Me" and "On the Banks of the Wabash," yielding for Paul an income of $80,000 (each title sold over a half million copies). Paul frequently came to the financial rescue of his family, and his connections with music publishers Howley-Haviland & Co. gave Dreiser the entree to propose a new journal--with him as editor--entitled Ev'ry Month, a large format magazine comprising four songs per issue and an array of fiction, poetry, interviews, book reviews, photographs, and advice for women.

The influences of Paul Dresser are manifold in Sister Carrie. Upon arriving in Chicago, Carrie is immediately drawn to the excitement and gaiety of popular entertainment. The theatrical world becomes her means to improve her financial life and free herself not only from the dreariness of working-class employment typical for young women of her background but also from the dependency on male companions to underwrite her room and board. Dreiser had an intimate view of this world through his brother Paul. In addition, many scholars have noted that the characters Charlie Drouet and George Hurstwood resemble Paul Dresser--not in terms of occupation but in terms of personality: tremendously affable but shallow, ultimately weak regarding their vanity and sensual appetites. On 30 January 1906 Paul Dresser, forty-eight years old, died of a heart attack at the home of his sister Emma; he was financially destitute and had been abandoned by most of his friends.

Fig. 2: Inscription: "For Tom Nelson my boyhood friend & schoolmate. Paul Dresser, Sept. 14th/1901"

Fig. 3: Combining as it did both music and written articles and stories, this publishing venture briefly united brothers Paul and Ted professionally. The first issue of Ev'ry Month was published in October 1895, but the September 1897 issue was Dreiser's last. The freedom of expression and selection that he thought was now his as conceiver and editor of Ev'ry Month proved hollow. Dreiser quarreled with his brother and demanded more money and editorial license from the publisher Howley, and they parted company.

Fig. 4 - Fig. 5: In 1897 Ted was with his brother Paul in the offices of Howley, Haviland & Co. While improvising on the piano, Paul urged Ted for a idea for a song. The resulting conversation led to "On the Banks of the Wabash"; Ted, in fact, wrote the first verse and chorus. In 1913 the State Assembly of Indiana adopted "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away" as the official state song.

Fig. 6: Beginning with "Dear Tedarino" and closing with "I am as ever the same old brother," this letter conveys the loyalty, camaraderie, and high spirits of Dreiser's eldest brother. Paul cautions Ted not to worry, claiming in his postscript that "The pen is mightier than the sword.' bigosh." This was at a particularly low time for Dreiser, who was suffering a nervous breakdown as a result of the suppression of Sister Carrie. Per usual, Paul shared his financial resources with his family, while also respecting Ted's pride by stating that he owed Dreiser royalties for "On the Banks of the Wabash."

Fig. 7: In 1919 Boni & Liveright published Dreiser's Twelve Men, personality sketches that illustrated the author's notion that goodness can be found in unconventional lives. Some of the essays were reworked material written as early as 1902, but "My Brother Paul" was a new piece that afforded Dreiser the opportunity to remember fondly the tender-hearted man whom he characterized as "generous to the point of self-destruction." Although reviews were generally favorable for Twelve Men, sales stagnated, with less than 2,000 copies sold in the first year. In 1924 publishers Haldeman-Julius reprinted two of the portraits from Twelve Men as Little Blue Book No. 660.

Fig. 8: Dreiser was summoned by his brother Ed to their sister Emma's apartment in New York on 30 January 1906, the night that Paul Dresser died.

Fig. 9 - Fig. 10: he first page of the sheet music, whose title became the focus of the 1942 motion picture about the life and career of Paul Dresser, imparts a sentimental lyric set to ukulele music. Sal was, in fact, Sallie Walker, Paul's former mistress, who operated a highly successful house of prostitution on Main Street in Evansville, Illinois. It was a combination of Paul's success as a composer and Sallie's success as a madam that allowed Paul to move his then-destitute mother into a small home in Evansville in the early 1880s

Fig. 11 - Fig. 12: After decades of false starts and tangled negotiations, a cinematic version of Paul Dresser's life story was finally produced by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1942. The Hollywood musical starred Victor Mature as Dresser and Rita Hayworth as Sally (Sal) Elliot; it was loosely based on Dreiser's essay "My Brother Paul" and included many of Dresser's songs. The rights for the movie and for the songs were sold for between $35,000 and $50,000, and the proceeds were divided among Dresser's surviving siblings (Theodore, Ed, Mame, and Sylvia).

Fig. 13: In this letter to his former secretary, sometimes literary agent, and loyal friend and supporter, Dreiser urges Lengel to see My Gal Sal and offers his reaction to the Hollywood biography--so long in the making--of his brother Paul.

"I was surprised and pleased at the skilful way the Fox Company developed Paul's life story as well as the gay nineties, and particularly his Gal Sal. It's truly charming and gay."

Born in 1857, John Paul Dreiser, Jr., eldest son of John Paul and Sarah Dreiser, was quick to flee the family, in particular, his stern father and the conventionality of small-town America. High-spirited and mischievous, Paul Dresser--the professional name that he adopted--was musically gifted. As a composer of popular songs, he enjoyed--at times--enormous financial success. In 1895 and in 1897, for example, he published his two biggest-selling hits, " Just Tell Them That You Saw Me" and "On the Banks of the Wabash," yielding for Paul an income of $80,000 (each title sold over a half million copies). Paul frequently came to the financial rescue of his family, and his connections with music publishers Howley-Haviland & Co. gave Dreiser the entree to propose a new journal--with him as editor--entitled Ev'ry Month, a large format magazine comprising four songs per issue and an array of fiction, poetry, interviews, book reviews, photographs, and advice for women.

The influences of Paul Dresser are manifold in Sister Carrie. Upon arriving in Chicago, Carrie is immediately drawn to the excitement and gaiety of popular entertainment. The theatrical world becomes her means to improve her financial life and free herself not only from the dreariness of working-class employment typical for young women of her background but also from the dependency on male companions to underwrite her room and board. Dreiser had an intimate view of this world through his brother Paul. In addition, many scholars have noted that the characters Charlie Drouet and George Hurstwood resemble Paul Dresser--not in terms of occupation but in terms of personality: tremendously affable but shallow, ultimately weak regarding their vanity and sensual appetites. On 30 January 1906 Paul Dresser, forty-eight years old, died of a heart attack at the home of his sister Emma; he was financially destitute and had been abandoned by most of his friends.

Fig. 2: Inscription: "For Tom Nelson my boyhood friend & schoolmate. Paul Dresser, Sept. 14th/1901"

Fig. 3: Combining as it did both music and written articles and stories, this publishing venture briefly united brothers Paul and Ted professionally. The first issue of Ev'ry Month was published in October 1895, but the September 1897 issue was Dreiser's last. The freedom of expression and selection that he thought was now his as conceiver and editor of Ev'ry Month proved hollow. Dreiser quarreled with his brother and demanded more money and editorial license from the publisher Howley, and they parted company.

Fig. 4 - Fig. 5: In 1897 Ted was with his brother Paul in the offices of Howley, Haviland & Co. While improvising on the piano, Paul urged Ted for a idea for a song. The resulting conversation led to "On the Banks of the Wabash"; Ted, in fact, wrote the first verse and chorus. In 1913 the State Assembly of Indiana adopted "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away" as the official state song.

Fig. 6: Beginning with "Dear Tedarino" and closing with "I am as ever the same old brother," this letter conveys the loyalty, camaraderie, and high spirits of Dreiser's eldest brother. Paul cautions Ted not to worry, claiming in his postscript that "The pen is mightier than the sword.' bigosh." This was at a particularly low time for Dreiser, who was suffering a nervous breakdown as a result of the suppression of Sister Carrie. Per usual, Paul shared his financial resources with his family, while also respecting Ted's pride by stating that he owed Dreiser royalties for "On the Banks of the Wabash."

Fig. 7: In 1919 Boni & Liveright published Dreiser's Twelve Men, personality sketches that illustrated the author's notion that goodness can be found in unconventional lives. Some of the essays were reworked material written as early as 1902, but "My Brother Paul" was a new piece that afforded Dreiser the opportunity to remember fondly the tender-hearted man whom he characterized as "generous to the point of self-destruction." Although reviews were generally favorable for Twelve Men, sales stagnated, with less than 2,000 copies sold in the first year. In 1924 publishers Haldeman-Julius reprinted two of the portraits from Twelve Men as Little Blue Book No. 660.

Fig. 8: Dreiser was summoned by his brother Ed to their sister Emma's apartment in New York on 30 January 1906, the night that Paul Dresser died.

Fig. 9 - Fig. 10: he first page of the sheet music, whose title became the focus of the 1942 motion picture about the life and career of Paul Dresser, imparts a sentimental lyric set to ukulele music. Sal was, in fact, Sallie Walker, Paul's former mistress, who operated a highly successful house of prostitution on Main Street in Evansville, Illinois. It was a combination of Paul's success as a composer and Sallie's success as a madam that allowed Paul to move his then-destitute mother into a small home in Evansville in the early 1880s

Fig. 11 - Fig. 12: After decades of false starts and tangled negotiations, a cinematic version of Paul Dresser's life story was finally produced by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1942. The Hollywood musical starred Victor Mature as Dresser and Rita Hayworth as Sally (Sal) Elliot; it was loosely based on Dreiser's essay "My Brother Paul" and included many of Dresser's songs. The rights for the movie and for the songs were sold for between $35,000 and $50,000, and the proceeds were divided among Dresser's surviving siblings (Theodore, Ed, Mame, and Sylvia).

Fig. 13: In this letter to his former secretary, sometimes literary agent, and loyal friend and supporter, Dreiser urges Lengel to see My Gal Sal and offers his reaction to the Hollywood biography--so long in the making--of his brother Paul.

"I was surprised and pleased at the skilful way the Fox Company developed Paul's life story as well as the gay nineties, and particularly his Gal Sal. It's truly charming and gay."

Born in 1857, John Paul Dreiser, Jr., eldest son of John Paul and Sarah Dreiser, was quick to flee the family, in particular, his stern father and the conventionality of small-town America. High-spirited and mischievous, Paul Dresser--the professional name that he adopted--was musically gifted. As a composer of popular songs, he enjoyed--at times--enormous financial success. In 1895 and in 1897, for example, he published his two biggest-selling hits, " Just Tell Them That You Saw Me" and "On the Banks of the Wabash," yielding for Paul an income of $80,000 (each title sold over a half million copies). Paul frequently came to the financial rescue of his family, and his connections with music publishers Howley-Haviland & Co. gave Dreiser the entree to propose a new journal--with him as editor--entitled Ev'ry Month, a large format magazine comprising four songs per issue and an array of fiction, poetry, interviews, book reviews, photographs, and advice for women.

The influences of Paul Dresser are manifold in Sister Carrie. Upon arriving in Chicago, Carrie is immediately drawn to the excitement and gaiety of popular entertainment. The theatrical world becomes her means to improve her financial life and free herself not only from the dreariness of working-class employment typical for young women of her background but also from the dependency on male companions to underwrite her room and board. Dreiser had an intimate view of this world through his brother Paul. In addition, many scholars have noted that the characters Charlie Drouet and George Hurstwood resemble Paul Dresser--not in terms of occupation but in terms of personality: tremendously affable but shallow, ultimately weak regarding their vanity and sensual appetites. On 30 January 1906 Paul Dresser, forty-eight years old, died of a heart attack at the home of his sister Emma; he was financially destitute and had been abandoned by most of his friends.

Fig. 2: Inscription: "For Tom Nelson my boyhood friend & schoolmate. Paul Dresser, Sept. 14th/1901"

Fig. 3: Combining as it did both music and written articles and stories, this publishing venture briefly united brothers Paul and Ted professionally. The first issue of Ev'ry Month was published in October 1895, but the September 1897 issue was Dreiser's last. The freedom of expression and selection that he thought was now his as conceiver and editor of Ev'ry Month proved hollow. Dreiser quarreled with his brother and demanded more money and editorial license from the publisher Howley, and they parted company.

Fig. 4 - Fig. 5: In 1897 Ted was with his brother Paul in the offices of Howley, Haviland & Co. While improvising on the piano, Paul urged Ted for a idea for a song. The resulting conversation led to "On the Banks of the Wabash"; Ted, in fact, wrote the first verse and chorus. In 1913 the State Assembly of Indiana adopted "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away" as the official state song.

Fig. 6: Beginning with "Dear Tedarino" and closing with "I am as ever the same old brother," this letter conveys the loyalty, camaraderie, and high spirits of Dreiser's eldest brother. Paul cautions Ted not to worry, claiming in his postscript that "The pen is mightier than the sword.' bigosh." This was at a particularly low time for Dreiser, who was suffering a nervous breakdown as a result of the suppression of Sister Carrie. Per usual, Paul shared his financial resources with his family, while also respecting Ted's pride by stating that he owed Dreiser royalties for "On the Banks of the Wabash."

Fig. 7: In 1919 Boni & Liveright published Dreiser's Twelve Men, personality sketches that illustrated the author's notion that goodness can be found in unconventional lives. Some of the essays were reworked material written as early as 1902, but "My Brother Paul" was a new piece that afforded Dreiser the opportunity to remember fondly the tender-hearted man whom he characterized as "generous to the point of self-destruction." Although reviews were generally favorable for Twelve Men, sales stagnated, with less than 2,000 copies sold in the first year. In 1924 publishers Haldeman-Julius reprinted two of the portraits from Twelve Men as Little Blue Book No. 660.

Fig. 8: Dreiser was summoned by his brother Ed to their sister Emma's apartment in New York on 30 January 1906, the night that Paul Dresser died.

Fig. 9 - Fig. 10: he first page of the sheet music, whose title became the focus of the 1942 motion picture about the life and career of Paul Dresser, imparts a sentimental lyric set to ukulele music. Sal was, in fact, Sallie Walker, Paul's former mistress, who operated a highly successful house of prostitution on Main Street in Evansville, Illinois. It was a combination of Paul's success as a composer and Sallie's success as a madam that allowed Paul to move his then-destitute mother into a small home in Evansville in the early 1880s

Fig. 11 - Fig. 12: After decades of false starts and tangled negotiations, a cinematic version of Paul Dresser's life story was finally produced by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1942. The Hollywood musical starred Victor Mature as Dresser and Rita Hayworth as Sally (Sal) Elliot; it was loosely based on Dreiser's essay "My Brother Paul" and included many of Dresser's songs. The rights for the movie and for the songs were sold for between $35,000 and $50,000, and the proceeds were divided among Dresser's surviving siblings (Theodore, Ed, Mame, and Sylvia).

Fig. 13: In this letter to his former secretary, sometimes literary agent, and loyal friend and supporter, Dreiser urges Lengel to see My Gal Sal and offers his reaction to the Hollywood biography--so long in the making--of his brother Paul.

"I was surprised and pleased at the skilful way the Fox Company developed Paul's life story as well as the gay nineties, and particularly his Gal Sal. It's truly charming and gay."

Born in 1857, John Paul Dreiser, Jr., eldest son of John Paul and Sarah Dreiser, was quick to flee the family, in particular, his stern father and the conventionality of small-town America. High-spirited and mischievous, Paul Dresser--the professional name that he adopted--was musically gifted. As a composer of popular songs, he enjoyed--at times--enormous financial success. In 1895 and in 1897, for example, he published his two biggest-selling hits, " Just Tell Them That You Saw Me" and "On the Banks of the Wabash," yielding for Paul an income of $80,000 (each title sold over a half million copies). Paul frequently came to the financial rescue of his family, and his connections with music publishers Howley-Haviland & Co. gave Dreiser the entree to propose a new journal--with him as editor--entitled Ev'ry Month, a large format magazine comprising four songs per issue and an array of fiction, poetry, interviews, book reviews, photographs, and advice for women.

The influences of Paul Dresser are manifold in Sister Carrie. Upon arriving in Chicago, Carrie is immediately drawn to the excitement and gaiety of popular entertainment. The theatrical world becomes her means to improve her financial life and free herself not only from the dreariness of working-class employment typical for young women of her background but also from the dependency on male companions to underwrite her room and board. Dreiser had an intimate view of this world through his brother Paul. In addition, many scholars have noted that the characters Charlie Drouet and George Hurstwood resemble Paul Dresser--not in terms of occupation but in terms of personality: tremendously affable but shallow, ultimately weak regarding their vanity and sensual appetites. On 30 January 1906 Paul Dresser, forty-eight years old, died of a heart attack at the home of his sister Emma; he was financially destitute and had been abandoned by most of his friends.

Fig. 2: Inscription: "For Tom Nelson my boyhood friend & schoolmate. Paul Dresser, Sept. 14th/1901"

Fig. 3: Combining as it did both music and written articles and stories, this publishing venture briefly united brothers Paul and Ted professionally. The first issue of Ev'ry Month was published in October 1895, but the September 1897 issue was Dreiser's last. The freedom of expression and selection that he thought was now his as conceiver and editor of Ev'ry Month proved hollow. Dreiser quarreled with his brother and demanded more money and editorial license from the publisher Howley, and they parted company.

Fig. 4 - Fig. 5: In 1897 Ted was with his brother Paul in the offices of Howley, Haviland & Co. While improvising on the piano, Paul urged Ted for a idea for a song. The resulting conversation led to "On the Banks of the Wabash"; Ted, in fact, wrote the first verse and chorus. In 1913 the State Assembly of Indiana adopted "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away" as the official state song.

Fig. 6: Beginning with "Dear Tedarino" and closing with "I am as ever the same old brother," this letter conveys the loyalty, camaraderie, and high spirits of Dreiser's eldest brother. Paul cautions Ted not to worry, claiming in his postscript that "The pen is mightier than the sword.' bigosh." This was at a particularly low time for Dreiser, who was suffering a nervous breakdown as a result of the suppression of Sister Carrie. Per usual, Paul shared his financial resources with his family, while also respecting Ted's pride by stating that he owed Dreiser royalties for "On the Banks of the Wabash."

Fig. 7: In 1919 Boni & Liveright published Dreiser's Twelve Men, personality sketches that illustrated the author's notion that goodness can be found in unconventional lives. Some of the essays were reworked material written as early as 1902, but "My Brother Paul" was a new piece that afforded Dreiser the opportunity to remember fondly the tender-hearted man whom he characterized as "generous to the point of self-destruction." Although reviews were generally favorable for Twelve Men, sales stagnated, with less than 2,000 copies sold in the first year. In 1924 publishers Haldeman-Julius reprinted two of the portraits from Twelve Men as Little Blue Book No. 660.

Fig. 8: Dreiser was summoned by his brother Ed to their sister Emma's apartment in New York on 30 January 1906, the night that Paul Dresser died.

Fig. 9 - Fig. 10: he first page of the sheet music, whose title became the focus of the 1942 motion picture about the life and career of Paul Dresser, imparts a sentimental lyric set to ukulele music. Sal was, in fact, Sallie Walker, Paul's former mistress, who operated a highly successful house of prostitution on Main Street in Evansville, Illinois. It was a combination of Paul's success as a composer and Sallie's success as a madam that allowed Paul to move his then-destitute mother into a small home in Evansville in the early 1880s

Fig. 11 - Fig. 12: After decades of false starts and tangled negotiations, a cinematic version of Paul Dresser's life story was finally produced by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1942. The Hollywood musical starred Victor Mature as Dresser and Rita Hayworth as Sally (Sal) Elliot; it was loosely based on Dreiser's essay "My Brother Paul" and included many of Dresser's songs. The rights for the movie and for the songs were sold for between $35,000 and $50,000, and the proceeds were divided among Dresser's surviving siblings (Theodore, Ed, Mame, and Sylvia).

Fig. 13: In this letter to his former secretary, sometimes literary agent, and loyal friend and supporter, Dreiser urges Lengel to see My Gal Sal and offers his reaction to the Hollywood biography--so long in the making--of his brother Paul.

"I was surprised and pleased at the skilful way the Fox Company developed Paul's life story as well as the gay nineties, and particularly his Gal Sal. It's truly charming and gay."

Born in 1857, John Paul Dreiser, Jr., eldest son of John Paul and Sarah Dreiser, was quick to flee the family, in particular, his stern father and the conventionality of small-town America. High-spirited and mischievous, Paul Dresser--the professional name that he adopted--was musically gifted. As a composer of popular songs, he enjoyed--at times--enormous financial success. In 1895 and in 1897, for example, he published his two biggest-selling hits, " Just Tell Them That You Saw Me" and "On the Banks of the Wabash," yielding for Paul an income of $80,000 (each title sold over a half million copies). Paul frequently came to the financial rescue of his family, and his connections with music publishers Howley-Haviland & Co. gave Dreiser the entree to propose a new journal--with him as editor--entitled Ev'ry Month, a large format magazine comprising four songs per issue and an array of fiction, poetry, interviews, book reviews, photographs, and advice for women.

The influences of Paul Dresser are manifold in Sister Carrie. Upon arriving in Chicago, Carrie is immediately drawn to the excitement and gaiety of popular entertainment. The theatrical world becomes her means to improve her financial life and free herself not only from the dreariness of working-class employment typical for young women of her background but also from the dependency on male companions to underwrite her room and board. Dreiser had an intimate view of this world through his brother Paul. In addition, many scholars have noted that the characters Charlie Drouet and George Hurstwood resemble Paul Dresser--not in terms of occupation but in terms of personality: tremendously affable but shallow, ultimately weak regarding their vanity and sensual appetites. On 30 January 1906 Paul Dresser, forty-eight years old, died of a heart attack at the home of his sister Emma; he was financially destitute and had been abandoned by most of his friends.

Fig. 2: Inscription: "For Tom Nelson my boyhood friend & schoolmate. Paul Dresser, Sept. 14th/1901"

Fig. 3: Combining as it did both music and written articles and stories, this publishing venture briefly united brothers Paul and Ted professionally. The first issue of Ev'ry Month was published in October 1895, but the September 1897 issue was Dreiser's last. The freedom of expression and selection that he thought was now his as conceiver and editor of Ev'ry Month proved hollow. Dreiser quarreled with his brother and demanded more money and editorial license from the publisher Howley, and they parted company.

Fig. 4 - Fig. 5: In 1897 Ted was with his brother Paul in the offices of Howley, Haviland & Co. While improvising on the piano, Paul urged Ted for a idea for a song. The resulting conversation led to "On the Banks of the Wabash"; Ted, in fact, wrote the first verse and chorus. In 1913 the State Assembly of Indiana adopted "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away" as the official state song.

Fig. 6: Beginning with "Dear Tedarino" and closing with "I am as ever the same old brother," this letter conveys the loyalty, camaraderie, and high spirits of Dreiser's eldest brother. Paul cautions Ted not to worry, claiming in his postscript that "The pen is mightier than the sword.' bigosh." This was at a particularly low time for Dreiser, who was suffering a nervous breakdown as a result of the suppression of Sister Carrie. Per usual, Paul shared his financial resources with his family, while also respecting Ted's pride by stating that he owed Dreiser royalties for "On the Banks of the Wabash."

Fig. 7: In 1919 Boni & Liveright published Dreiser's Twelve Men, personality sketches that illustrated the author's notion that goodness can be found in unconventional lives. Some of the essays were reworked material written as early as 1902, but "My Brother Paul" was a new piece that afforded Dreiser the opportunity to remember fondly the tender-hearted man whom he characterized as "generous to the point of self-destruction." Although reviews were generally favorable for Twelve Men, sales stagnated, with less than 2,000 copies sold in the first year. In 1924 publishers Haldeman-Julius reprinted two of the portraits from Twelve Men as Little Blue Book No. 660.

Fig. 8: Dreiser was summoned by his brother Ed to their sister Emma's apartment in New York on 30 January 1906, the night that Paul Dresser died.

Fig. 9 - Fig. 10: he first page of the sheet music, whose title became the focus of the 1942 motion picture about the life and career of Paul Dresser, imparts a sentimental lyric set to ukulele music. Sal was, in fact, Sallie Walker, Paul's former mistress, who operated a highly successful house of prostitution on Main Street in Evansville, Illinois. It was a combination of Paul's success as a composer and Sallie's success as a madam that allowed Paul to move his then-destitute mother into a small home in Evansville in the early 1880s

Fig. 11 - Fig. 12: After decades of false starts and tangled negotiations, a cinematic version of Paul Dresser's life story was finally produced by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1942. The Hollywood musical starred Victor Mature as Dresser and Rita Hayworth as Sally (Sal) Elliot; it was loosely based on Dreiser's essay "My Brother Paul" and included many of Dresser's songs. The rights for the movie and for the songs were sold for between $35,000 and $50,000, and the proceeds were divided among Dresser's surviving siblings (Theodore, Ed, Mame, and Sylvia).

Fig. 13: In this letter to his former secretary, sometimes literary agent, and loyal friend and supporter, Dreiser urges Lengel to see My Gal Sal and offers his reaction to the Hollywood biography--so long in the making--of his brother Paul.

"I was surprised and pleased at the skilful way the Fox Company developed Paul's life story as well as the gay nineties, and particularly his Gal Sal. It's truly charming and gay."

Born in 1857, John Paul Dreiser, Jr., eldest son of John Paul and Sarah Dreiser, was quick to flee the family, in particular, his stern father and the conventionality of small-town America. High-spirited and mischievous, Paul Dresser--the professional name that he adopted--was musically gifted. As a composer of popular songs, he enjoyed--at times--enormous financial success. In 1895 and in 1897, for example, he published his two biggest-selling hits, " Just Tell Them That You Saw Me" and "On the Banks of the Wabash," yielding for Paul an income of $80,000 (each title sold over a half million copies). Paul frequently came to the financial rescue of his family, and his connections with music publishers Howley-Haviland & Co. gave Dreiser the entree to propose a new journal--with him as editor--entitled Ev'ry Month, a large format magazine comprising four songs per issue and an array of fiction, poetry, interviews, book reviews, photographs, and advice for women.

The influences of Paul Dresser are manifold in Sister Carrie. Upon arriving in Chicago, Carrie is immediately drawn to the excitement and gaiety of popular entertainment. The theatrical world becomes her means to improve her financial life and free herself not only from the dreariness of working-class employment typical for young women of her background but also from the dependency on male companions to underwrite her room and board. Dreiser had an intimate view of this world through his brother Paul. In addition, many scholars have noted that the characters Charlie Drouet and George Hurstwood resemble Paul Dresser--not in terms of occupation but in terms of personality: tremendously affable but shallow, ultimately weak regarding their vanity and sensual appetites. On 30 January 1906 Paul Dresser, forty-eight years old, died of a heart attack at the home of his sister Emma; he was financially destitute and had been abandoned by most of his friends.

Fig. 2: Inscription: "For Tom Nelson my boyhood friend & schoolmate. Paul Dresser, Sept. 14th/1901"

Fig. 3: Combining as it did both music and written articles and stories, this publishing venture briefly united brothers Paul and Ted professionally. The first issue of Ev'ry Month was published in October 1895, but the September 1897 issue was Dreiser's last. The freedom of expression and selection that he thought was now his as conceiver and editor of Ev'ry Month proved hollow. Dreiser quarreled with his brother and demanded more money and editorial license from the publisher Howley, and they parted company.

Fig. 4 - Fig. 5: In 1897 Ted was with his brother Paul in the offices of Howley, Haviland & Co. While improvising on the piano, Paul urged Ted for a idea for a song. The resulting conversation led to "On the Banks of the Wabash"; Ted, in fact, wrote the first verse and chorus. In 1913 the State Assembly of Indiana adopted "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away" as the official state song.

Fig. 6: Beginning with "Dear Tedarino" and closing with "I am as ever the same old brother," this letter conveys the loyalty, camaraderie, and high spirits of Dreiser's eldest brother. Paul cautions Ted not to worry, claiming in his postscript that "The pen is mightier than the sword.' bigosh." This was at a particularly low time for Dreiser, who was suffering a nervous breakdown as a result of the suppression of Sister Carrie. Per usual, Paul shared his financial resources with his family, while also respecting Ted's pride by stating that he owed Dreiser royalties for "On the Banks of the Wabash."

Fig. 7: In 1919 Boni & Liveright published Dreiser's Twelve Men, personality sketches that illustrated the author's notion that goodness can be found in unconventional lives. Some of the essays were reworked material written as early as 1902, but "My Brother Paul" was a new piece that afforded Dreiser the opportunity to remember fondly the tender-hearted man whom he characterized as "generous to the point of self-destruction." Although reviews were generally favorable for Twelve Men, sales stagnated, with less than 2,000 copies sold in the first year. In 1924 publishers Haldeman-Julius reprinted two of the portraits from Twelve Men as Little Blue Book No. 660.

Fig. 8: Dreiser was summoned by his brother Ed to their sister Emma's apartment in New York on 30 January 1906, the night that Paul Dresser died.