Doing Wissenschaft

Judaic Studies 2014-2015 Fellows at the University of Pennsylvania

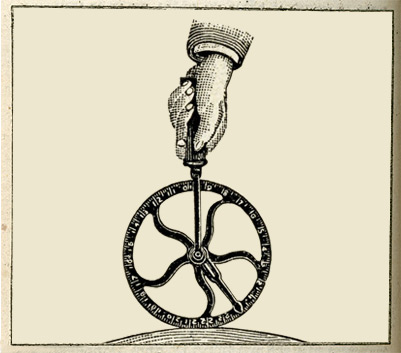

Cover design based on the image used for the Spring 2015 Gruss Colloquium of this year's research group on Wissenschaft des Judentums.

Introduction

From its inception, Jewish studies was a transnational endeavor characterized by a network of scholars emerging from different seedbeds. In time, modern rabbinical seminaries in central Europe and universities in France, England, the US and Israel would provide new and necessary forms of institutionalization. The needs and strategies of the discipline and its political and cultural functions varied in different countries and political contexts. The turn to history in the 19th century fundamentally recast the nature of Jewish thinking in Europe and beyond, influencing even those who challenged or rejected the dominance and mandate of historical-critical scholarship. The predominant narrative in this history of the academic study of Jews and Judaism is that of the Wissenschaft des Judentums (WdJ), which fulfilled crucial cultural, political, and religious functions in its day, and which, despite recent scholarship, remains to be fully contextualized. This past year's Fellows explored critical questions about how academic categories and methodologies have framed how Jews and Judaism are understood

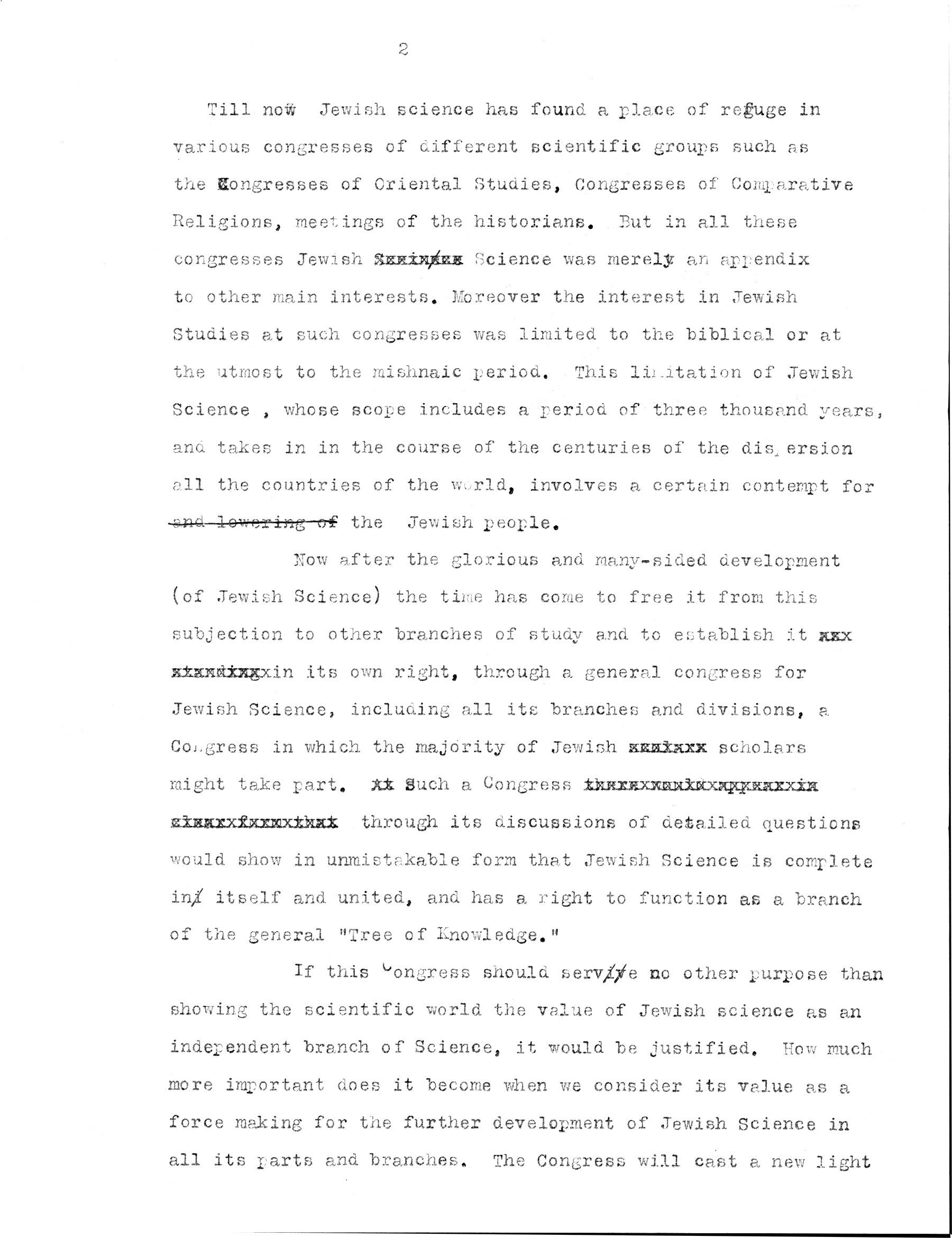

The Making of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Kenesiyah gedolah le-hokhmat yisra’el)

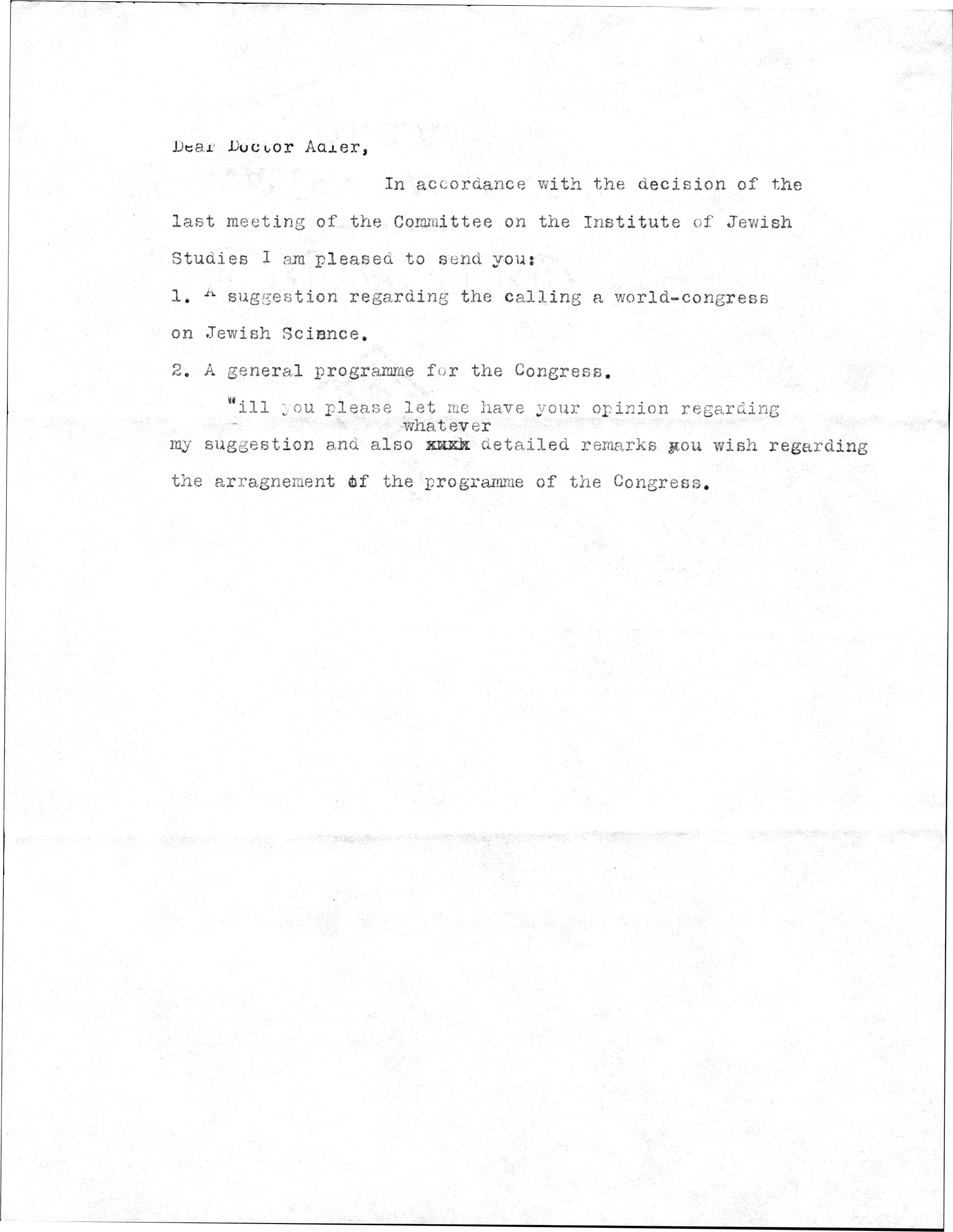

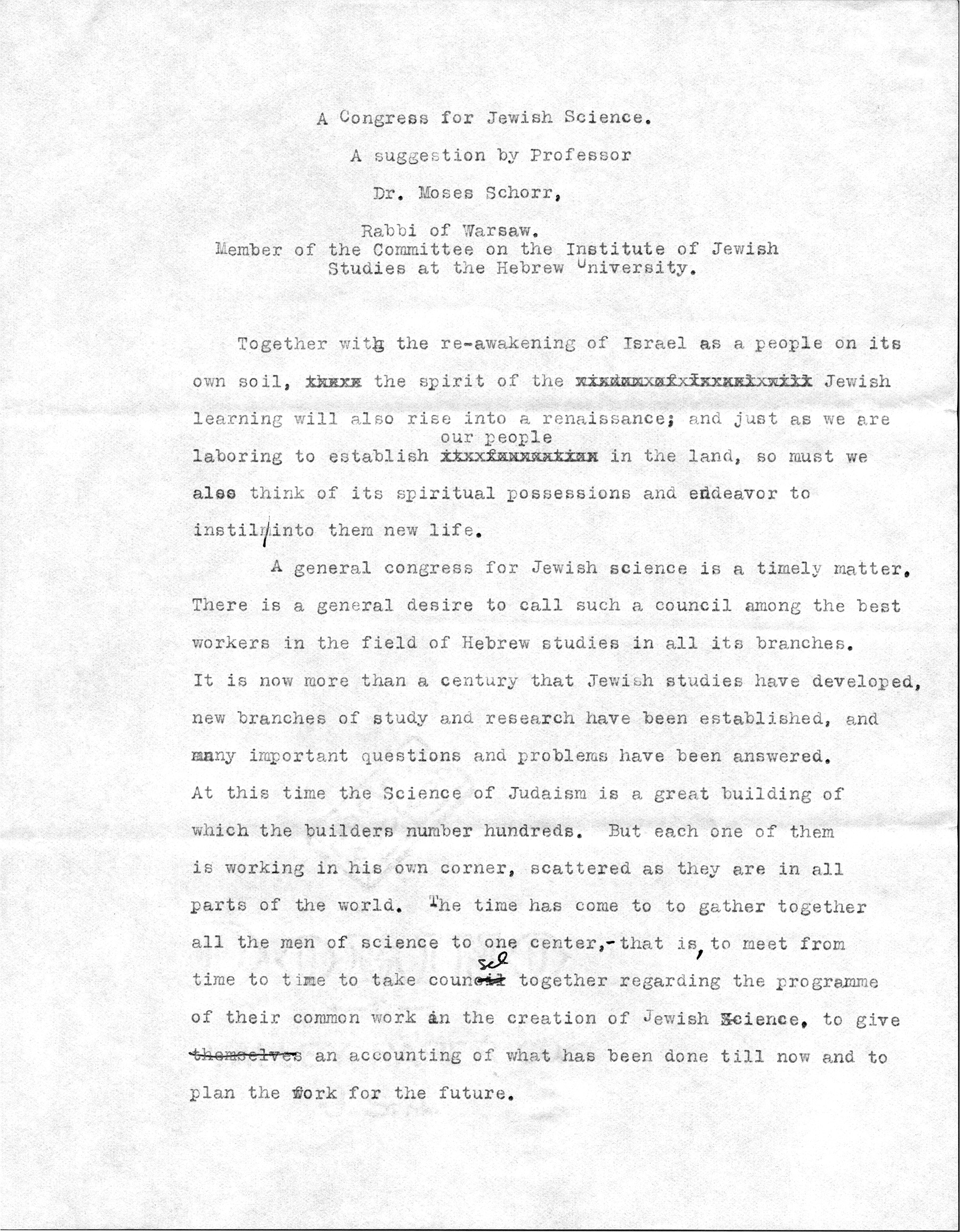

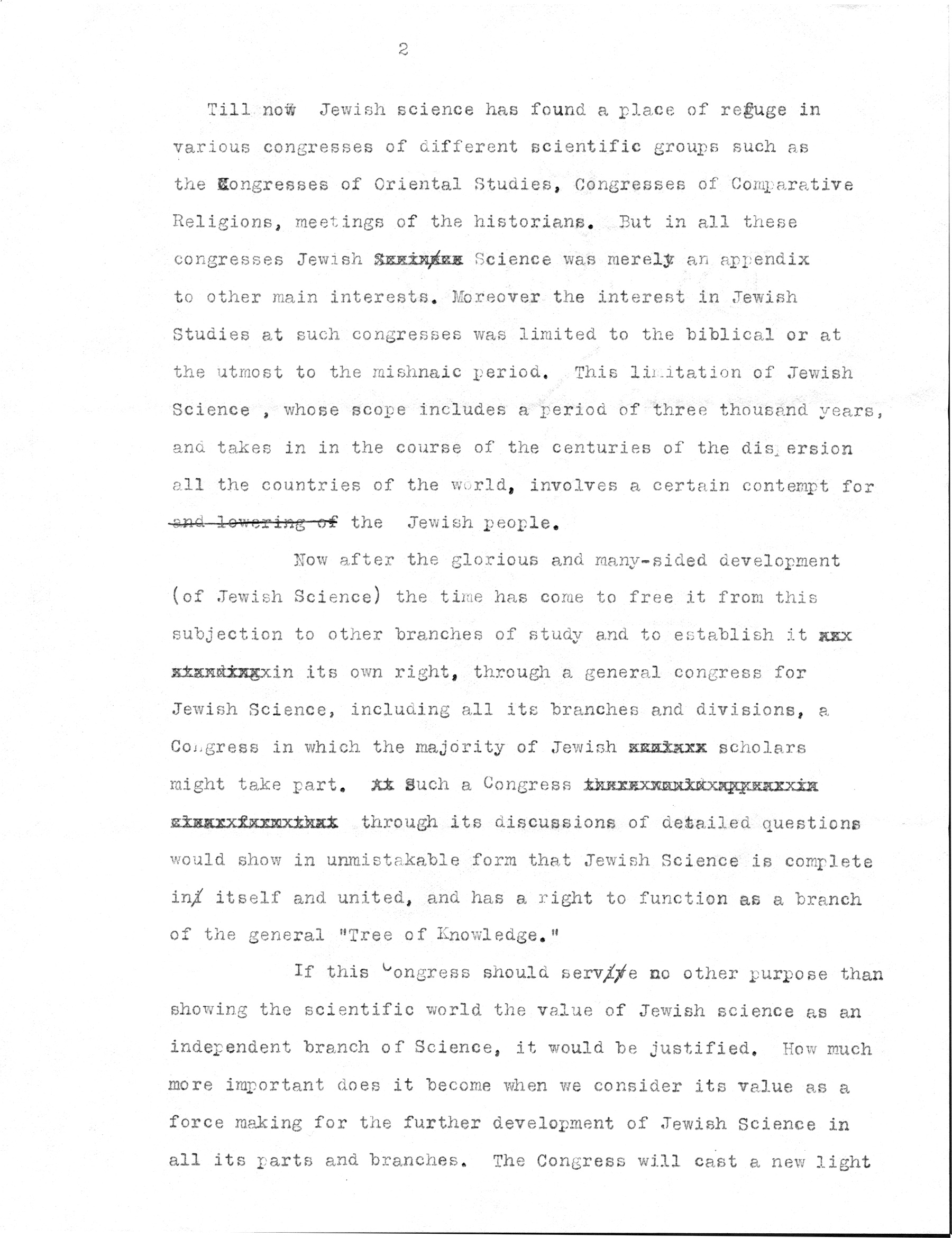

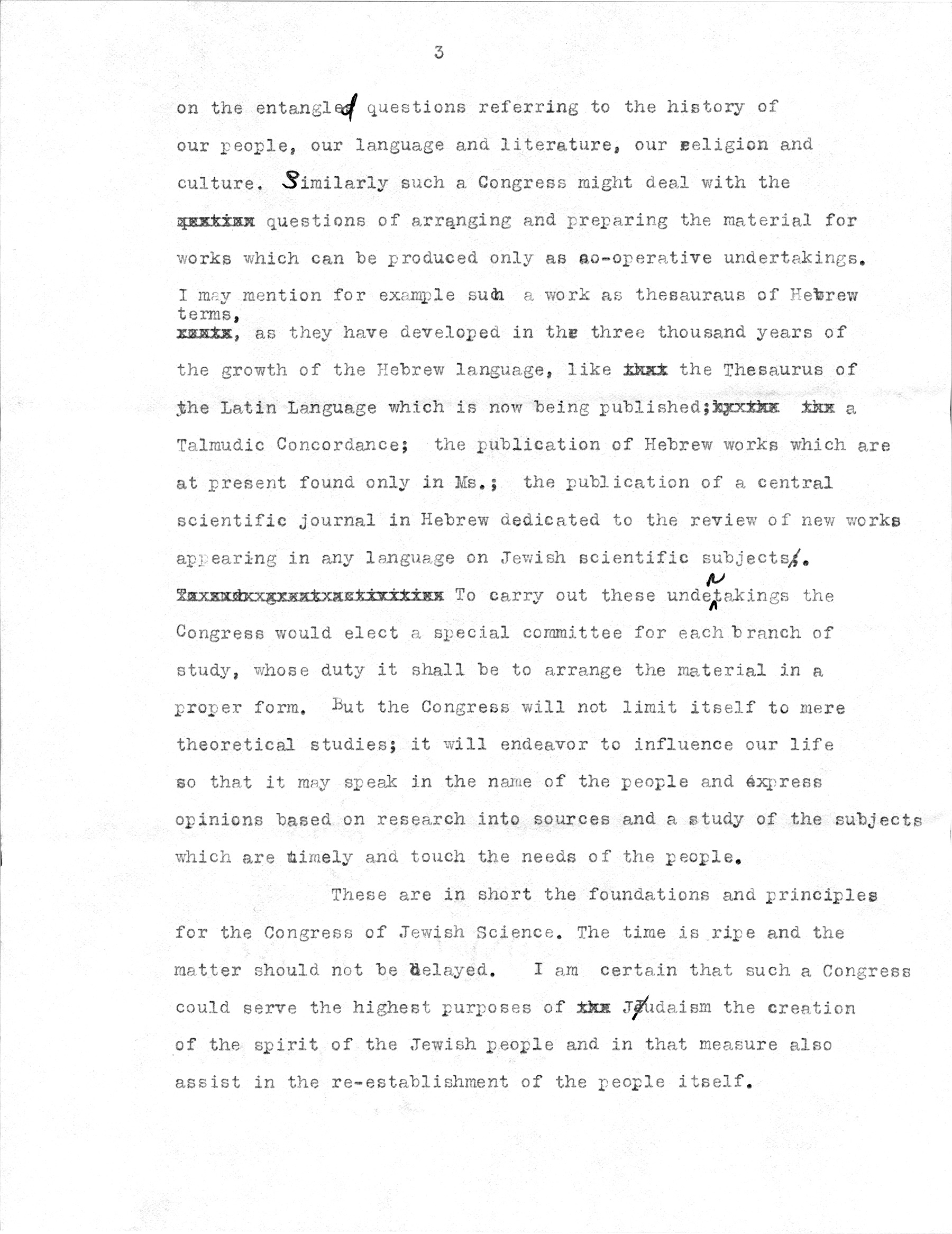

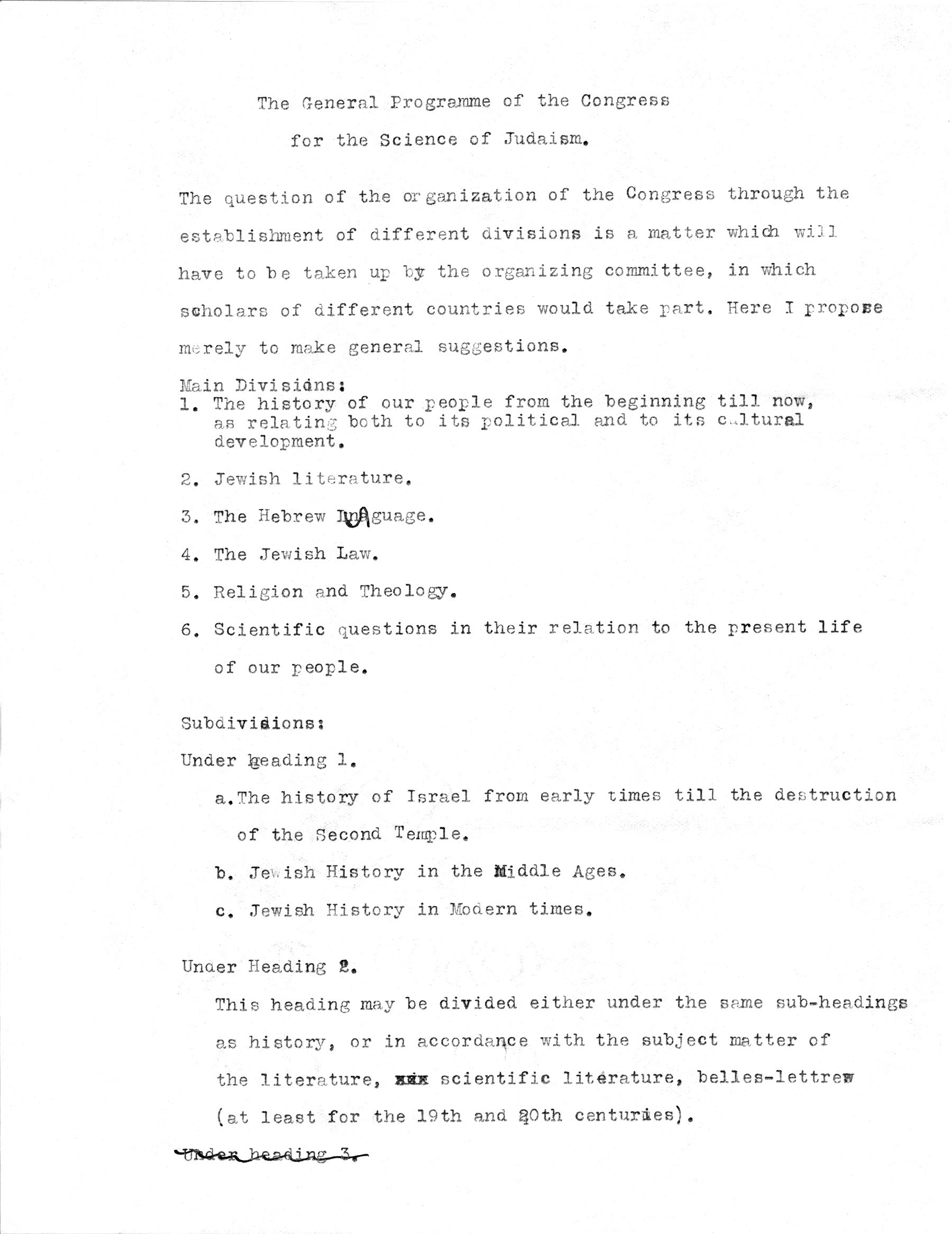

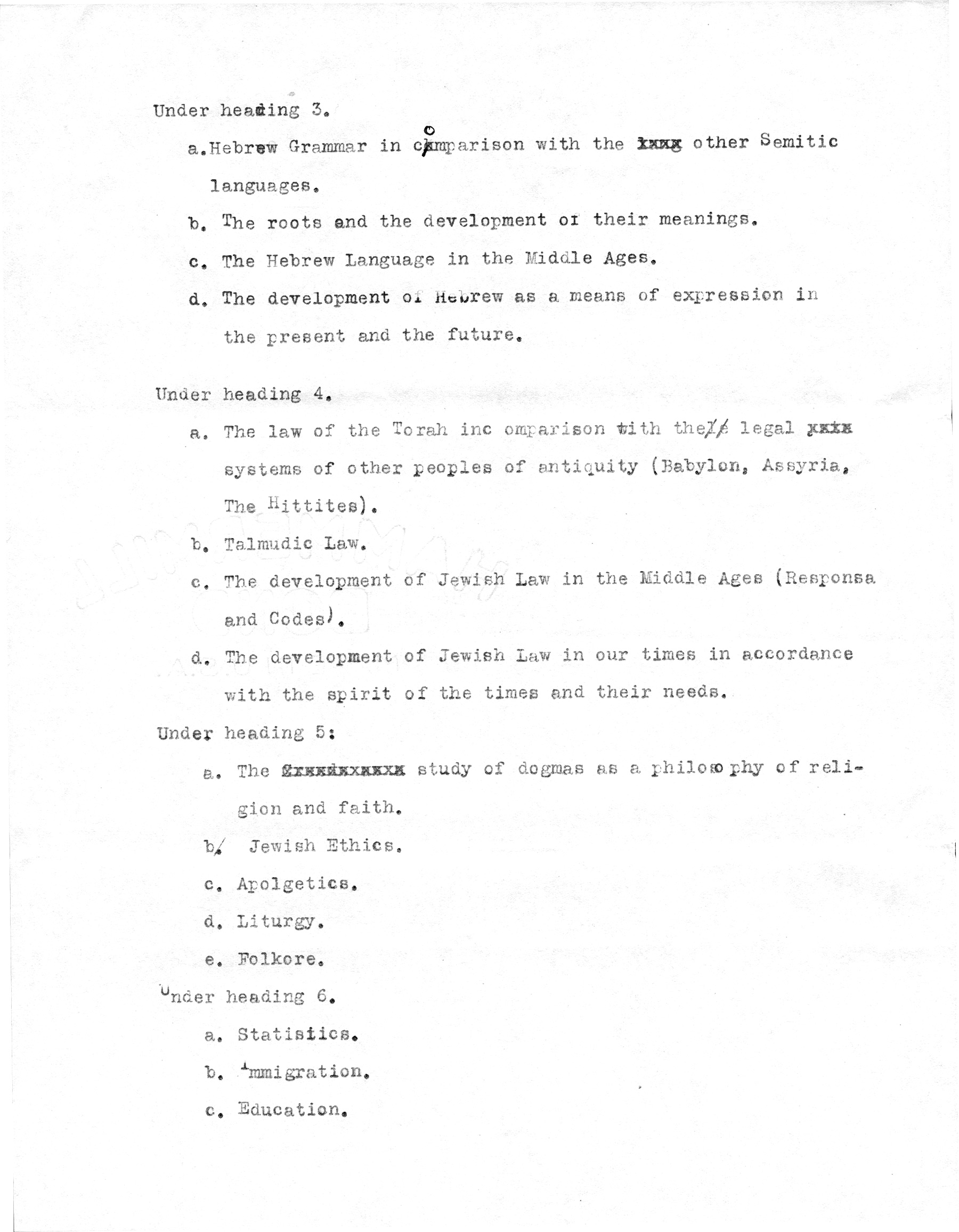

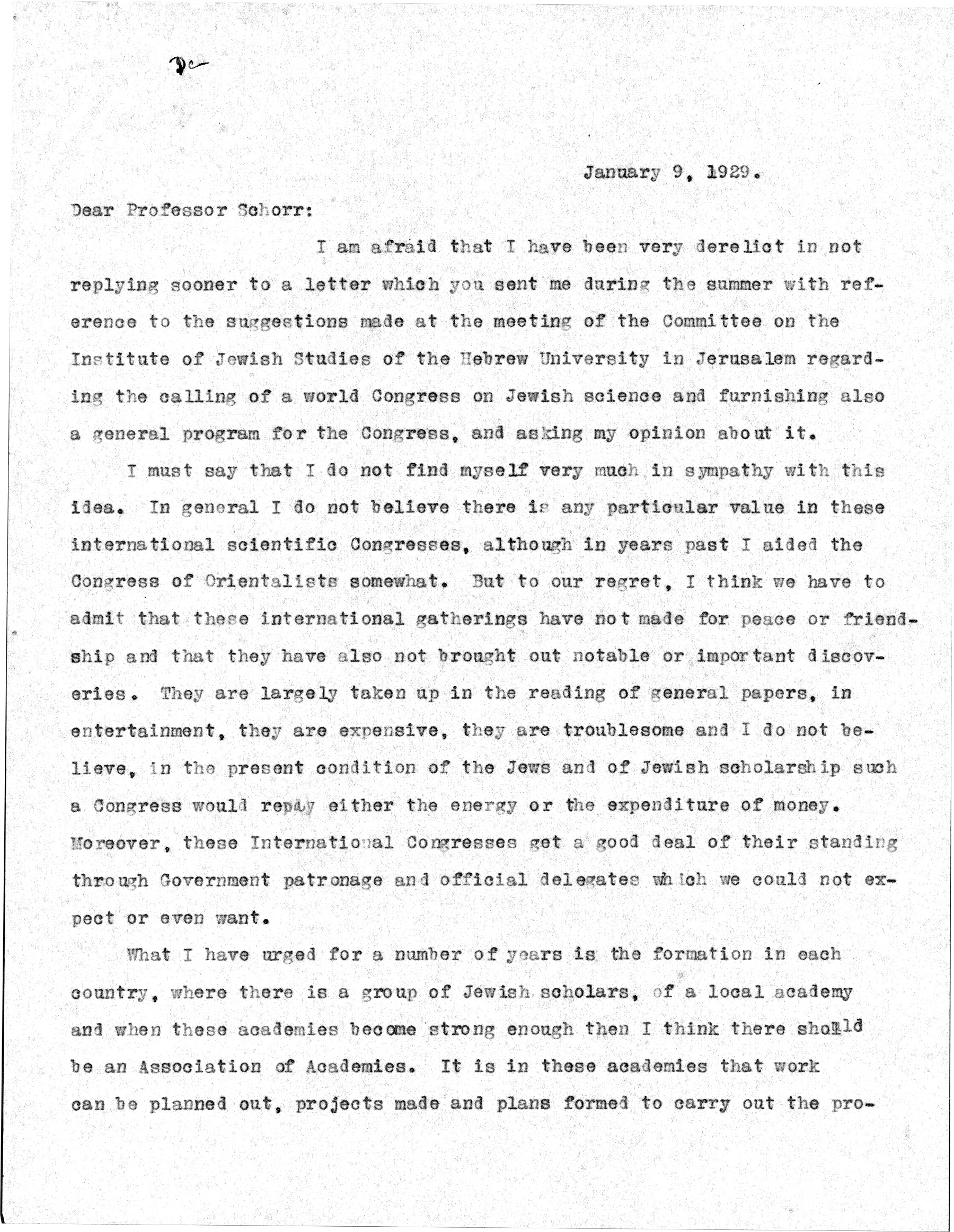

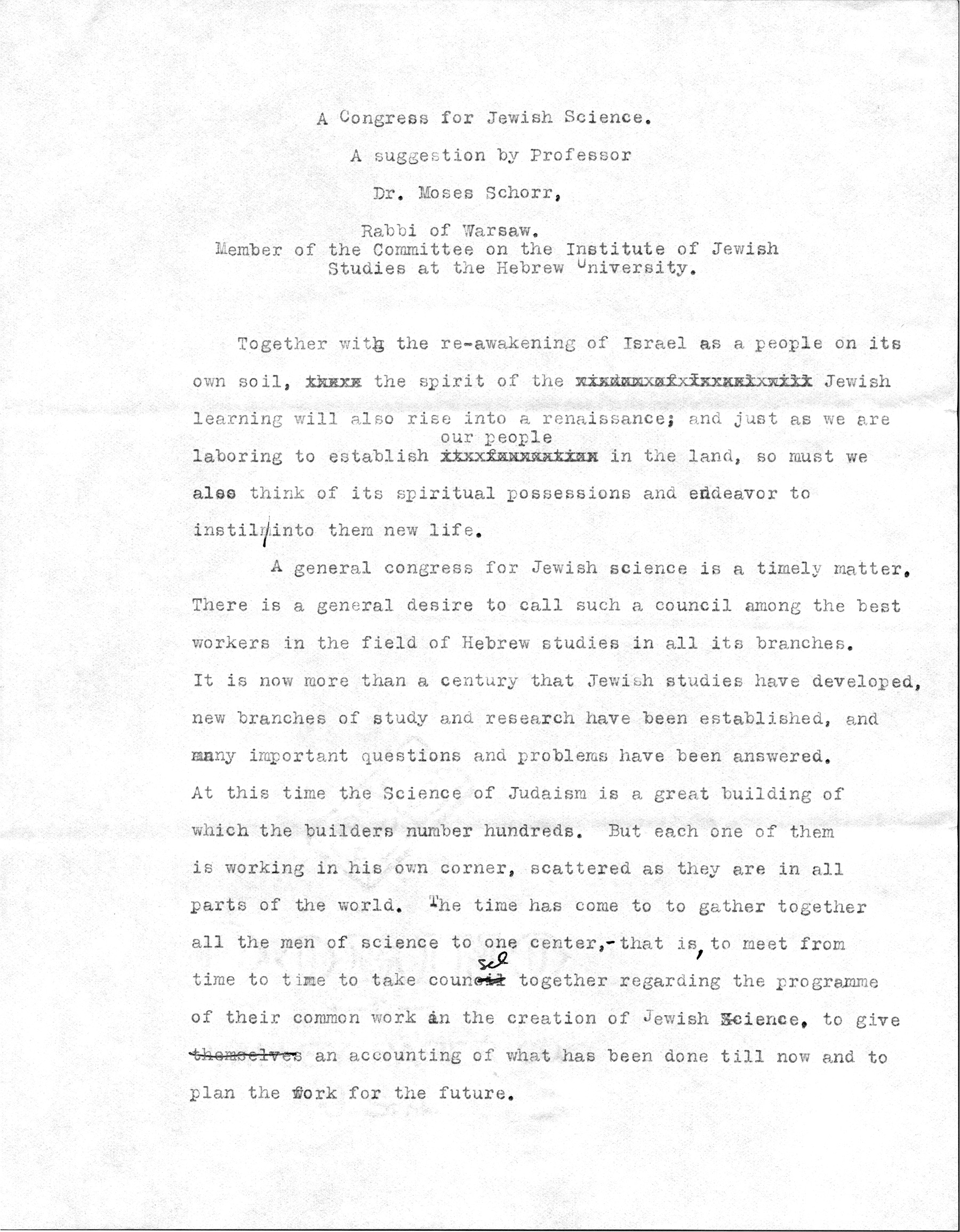

Following a festive inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, Jewish scholars who formed the Governing Council of the Institute of Jewish Studies discussed the need to create an international organization representing all aspects of Jewish studies. A member of the Council - Mojżesz Schorr (1874-1941)

Cyrus Adler (1863-1940)

The Making of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Kenesiyah gedolah le-hokhmat yisra’el)

Following a festive inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, Jewish scholars who formed the Governing Council of the Institute of Jewish Studies discussed the need to create an international organization representing all aspects of Jewish studies. A member of the Council - Mojżesz Schorr (1874-1941)

Cyrus Adler (1863-1940)

The Making of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Kenesiyah gedolah le-hokhmat yisra’el)

Following a festive inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, Jewish scholars who formed the Governing Council of the Institute of Jewish Studies discussed the need to create an international organization representing all aspects of Jewish studies. A member of the Council - Mojżesz Schorr (1874-1941)

Cyrus Adler (1863-1940)

The Making of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Kenesiyah gedolah le-hokhmat yisra’el)

Following a festive inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, Jewish scholars who formed the Governing Council of the Institute of Jewish Studies discussed the need to create an international organization representing all aspects of Jewish studies. A member of the Council - Mojżesz Schorr (1874-1941)

Cyrus Adler (1863-1940)

The Making of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Kenesiyah gedolah le-hokhmat yisra’el)

Following a festive inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, Jewish scholars who formed the Governing Council of the Institute of Jewish Studies discussed the need to create an international organization representing all aspects of Jewish studies. A member of the Council - Mojżesz Schorr (1874-1941)

Cyrus Adler (1863-1940)

The Making of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Kenesiyah gedolah le-hokhmat yisra’el)

Following a festive inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, Jewish scholars who formed the Governing Council of the Institute of Jewish Studies discussed the need to create an international organization representing all aspects of Jewish studies. A member of the Council - Mojżesz Schorr (1874-1941)

Cyrus Adler (1863-1940)

The Making of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Kenesiyah gedolah le-hokhmat yisra’el)

Following a festive inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, Jewish scholars who formed the Governing Council of the Institute of Jewish Studies discussed the need to create an international organization representing all aspects of Jewish studies. A member of the Council - Mojżesz Schorr (1874-1941)

Cyrus Adler (1863-1940)

The Making of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Kenesiyah gedolah le-hokhmat yisra’el)

Following a festive inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, Jewish scholars who formed the Governing Council of the Institute of Jewish Studies discussed the need to create an international organization representing all aspects of Jewish studies. A member of the Council - Mojżesz Schorr (1874-1941)

Cyrus Adler (1863-1940)

The Making of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Kenesiyah gedolah le-hokhmat yisra’el)

Following a festive inauguration of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, Jewish scholars who formed the Governing Council of the Institute of Jewish Studies discussed the need to create an international organization representing all aspects of Jewish studies. A member of the Council - Mojżesz Schorr (1874-1941)

Cyrus Adler (1863-1940)

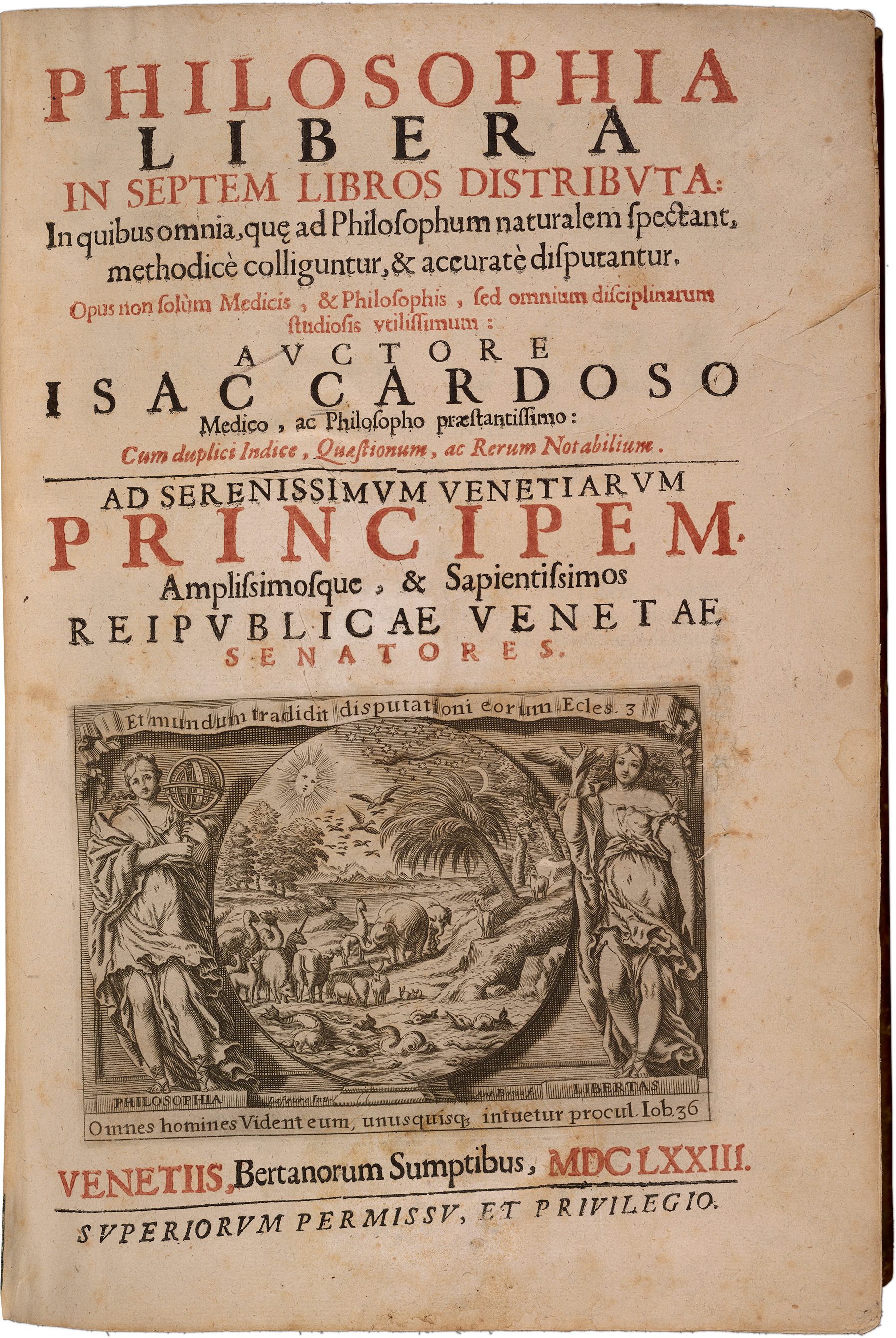

Cardoso, Philosophia Libera

The physician and philosopher Isaac Cardoso (d. 1683), who began life as a converso in Spain and died a professing Jew in Italy, published a lavish folio volume in 1673 entitled Philosophia Libera. Cardoso had received his medical education in Salamanca, and published his book in one of Europe's most important printing centers: Venice. The book is a schematic survey and critique of the history of philosophy, and contains much information on the Jewish origins of philosophy and science. Two scriptural quotations are prominently featured on the frontispiece. One is directly related to the book's theme, and is taken from the thirty-sixth chapter of Job. Elihu proclaims the majesty of God''s creation: "All people have looked on it; everyone watches it from far away." Cardoso's aim was to "look on it" from a much closer perspective. Indeed Philosophia Libera does so and offers a fine justification for studying nature: "we shall investigate Nature and its Founder, so that from the world and its multitude of things, as if by a ladder, with enlightened and instructed mind, we may be lifted to God its Maker; for His creatures are the ladder by which we ascend to God, the organ with which we praise God, and the school in which we learn God." There is perhaps no better summary of Cardoso's mission, as well as that of scientifically-inclined Jews in Italy and Spain from the Middle Ages through the Enlightenment.

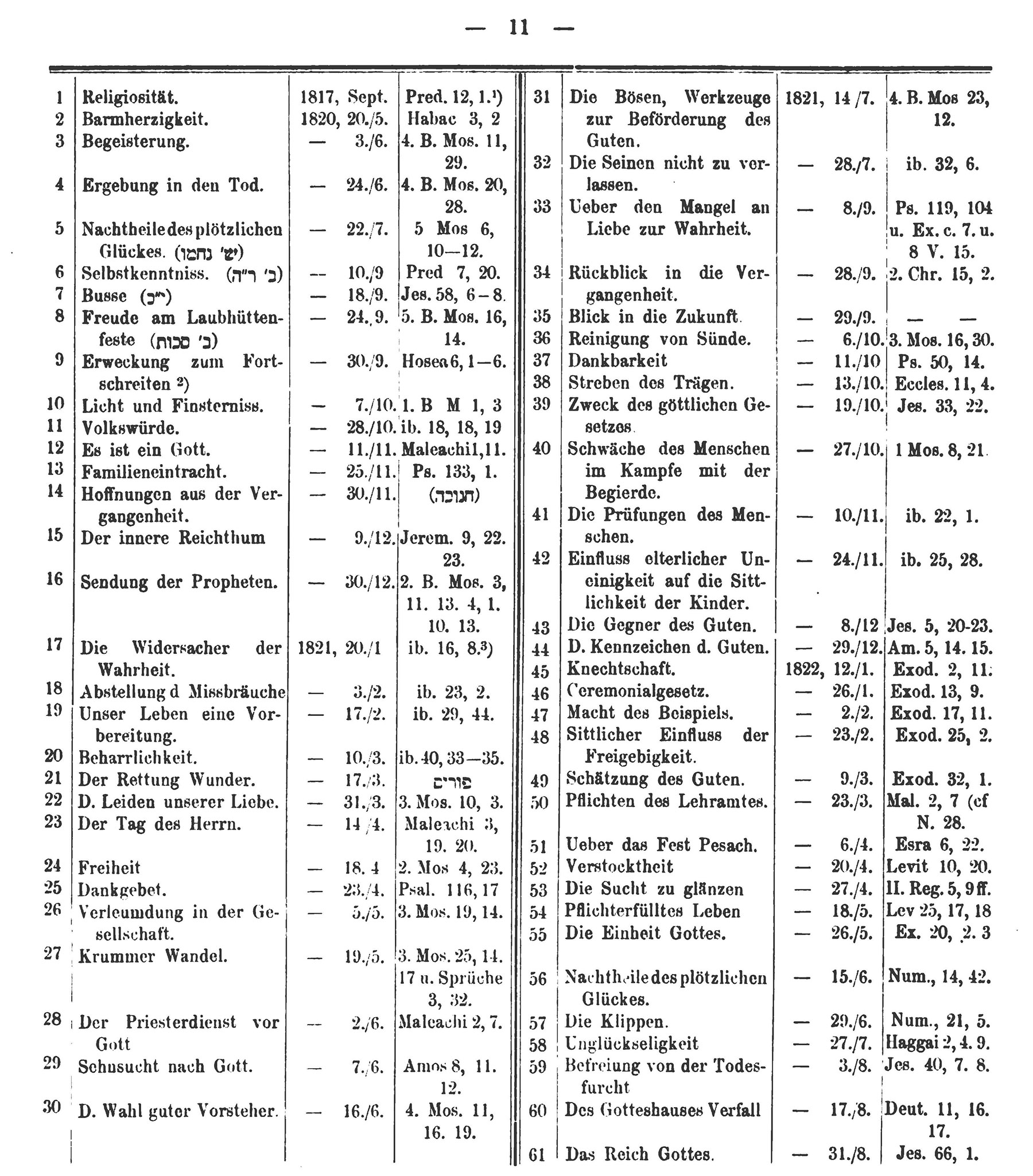

Honoring a Founder: From the Life of Leopold Zunz, edited by Siegmund Maybaum

In 1894, on the centenary of the birth of Leopold Zunz (1794-1886), the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums in Berlin, published its 12th annual report together with a supplement devoted to the great scholar whom the institution saw as its founder. Zunz had called for the revival of scholarship devoted to Jewish literature in a famous 1818 essay, "On Rabbinic Literature." The wealth of scholarly publications that appeared in the following decades testify to the reception of his call. Although most of Zunz's scholarly oeuvre was decidedly not popular and sometimes difficult to digest, Zunz's persona and life were represented in popular terms after his death. This 1894 publication by Maybaum (1844-1919), himself a great scholar of Jewish antiquity and late antiquity, gathered some of Zunz's personal correspondence from the years between 1818 and 1839, when Zunz struggled to secure a permanent position for himself as a rabbi or communal teacher. The correspondence consists mainly of his applications for candidacy and requests for assistance as well as a few rejections and negative appraisals sent by or about him. In Maybaum's words, "these failed attempts ... led him to the realization that his nature was suited only for work in complete independence" (p. 2). That is to say, they mark Zunz's turn to Wissenschaft (scholarship) alone and for its own sake.

The attached image is from Maybaum p. 11 and consists of Maybaum's reproduction of a chart that Zunz prepared in which he documented all the sermons he had given at the "German Synagogue in Berlin." The table lists the date of the sermon and the verse(s) that it discussed.

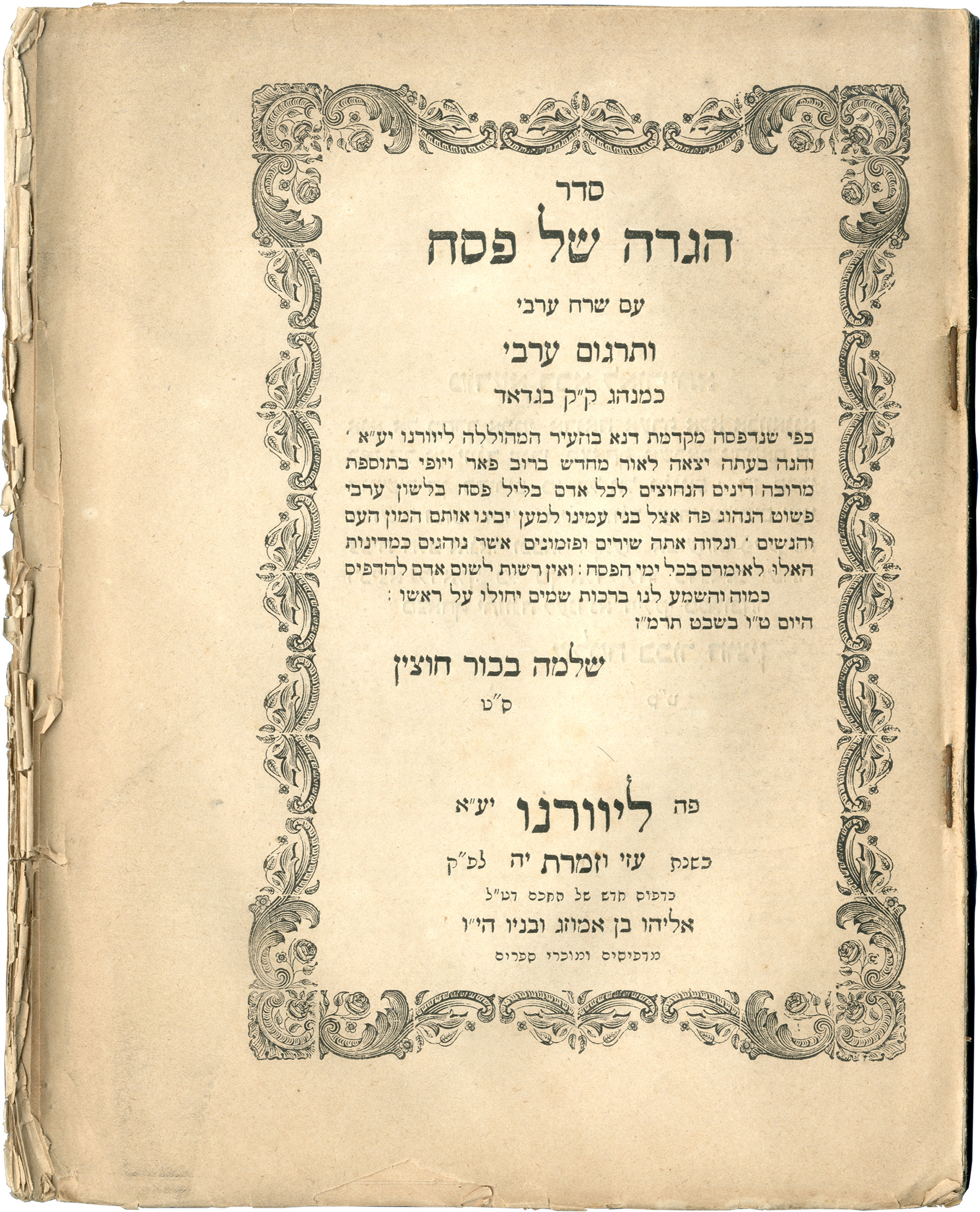

Elia Benamozegh and the printing of Levantine Jewish scholarship

An Italian rabbi, kabbalist, and thinker of Moroccan descent who lived in the Tuscan port city of Livorno, Elia Benamozegh (1823-1900) authored an abundance of works, encompassing exegesis, historical studies and various newspaper contributions, written in Hebrew, Italian and French. Through his posthumous masterwork, Israel and Humanity (1914), he significantly influenced the Christian-Jewish dialogue in Europe and rekindled the Noachide movement. In the books penned in French or Italian, brimming with references to Western philosophy and literature, he never made mention of his Oriental roots and rarely cited Sephardic contemporary authors. Yet his publishing activities situated him in the Middle East and North-African world. If various prayer books, spanning all Sephardic rituals, arguably signal a more commercial side of his activity, Benamozegh also showed perceptiveness with regards to his selection of Sephardic thinkers.

The catalogue of the volumes he published demonstrate his commitment to foster a sense of identity which embraces tradition in a modern key, as well as a sense of unity of Oriental Jews. And, because his endeavors displeased some more conservative actors, Benamozegh seems to have used his press as a way to publish his like-minded contemporaries, thus mapping out a landscape of modern Sephardic thought. This is certainly the case for the haggadah revised by Shelomoh Bekhor Hutsin (1843-1892) which Benamozegh published in 1887. This book, printed in Judeo-Arabic, Arabic, and Hebrew, according to the Baghdadi minhag (liturgical custom), lies at the juncture of tradition and modernity. Hutsin was a student of rabbi Abdallah Somekh (1813-1902) and a graduate of the very selective Yeshiva set up by Somekh, called Beth Zilkha, from which all the graduates became community leaders. Hutsin wrote liturgical works, numerous articles and was an advocate of a version of Jewish enlightenment that was respectful of Jewish values and modern culture. In 1863, Barukh Moshe Misrahi established the first press of Baghdad. In 1882 the activities ceased, only to be resumed by Hutsin in 1888– this is exactly in the interim that Benamozegh published this Haggadah. This cooperation seems to show that Benamozegh was in the know about both the business side but also the life of ideas in Baghdad; it is evidence of the sustained intense intellectual contacts in the Mediterranean and the Levant

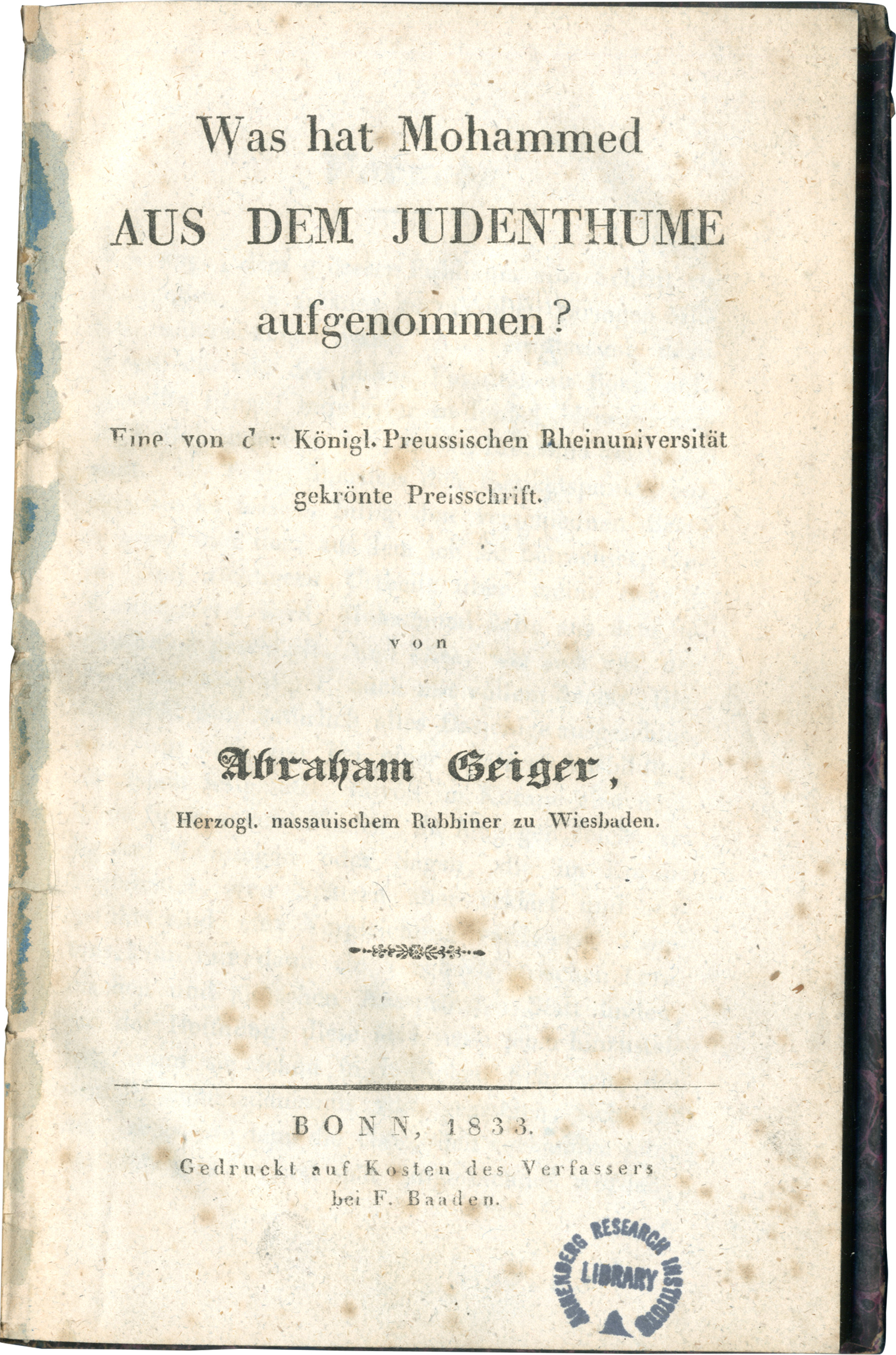

Abraham Geiger and Quranic scholarship

In 1833, Abraham Geiger published Was hat Mohammed aus dem Judenthume aufgenommen? (“What did Muhammad borrow from Judaism?”). The essay, originally written in Latin and submitted to the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Bonn the previous year, was awarded a prize by the Faculty in August of 1832. Geiger's work has rightly been judged a methodological breakthrough and a turning point in European scholarship about the origins and sources of Islam. Geiger was the first scholar to "historize" the Qurʾān, i.e. to read the text critically in light of the historical contexts in which it was written. For example, Geiger scrutinizes the vocabulary of the Qur’ān in order to identify words and ideas which were, as he assumed, borrowed from Judaism and earlier Jewish traditions. Although some of Geiger's assumptions may today appear naïve and judgmental, his major contribution was to approach the relationship between the two religions conceptually rather than polemically, and systematically rather than haphazardly. The book aroused something of a stir among Geiger's Christian colleagues by portraying the Prophet Muhammad as "a sincere religious enthusiast (schwärmer) who was himself convinced of his divine mission" and not as a skilled imposter and charlatan, as viewed by Silvestre de Sacy, the leading Arabist of the time. But the main importance of Geiger's Was hat Mohammed aus dem Judenthume aufgenommen? lies in the fact that it has for the first time posed questions that stand in the center of Qur’ānic research till today.

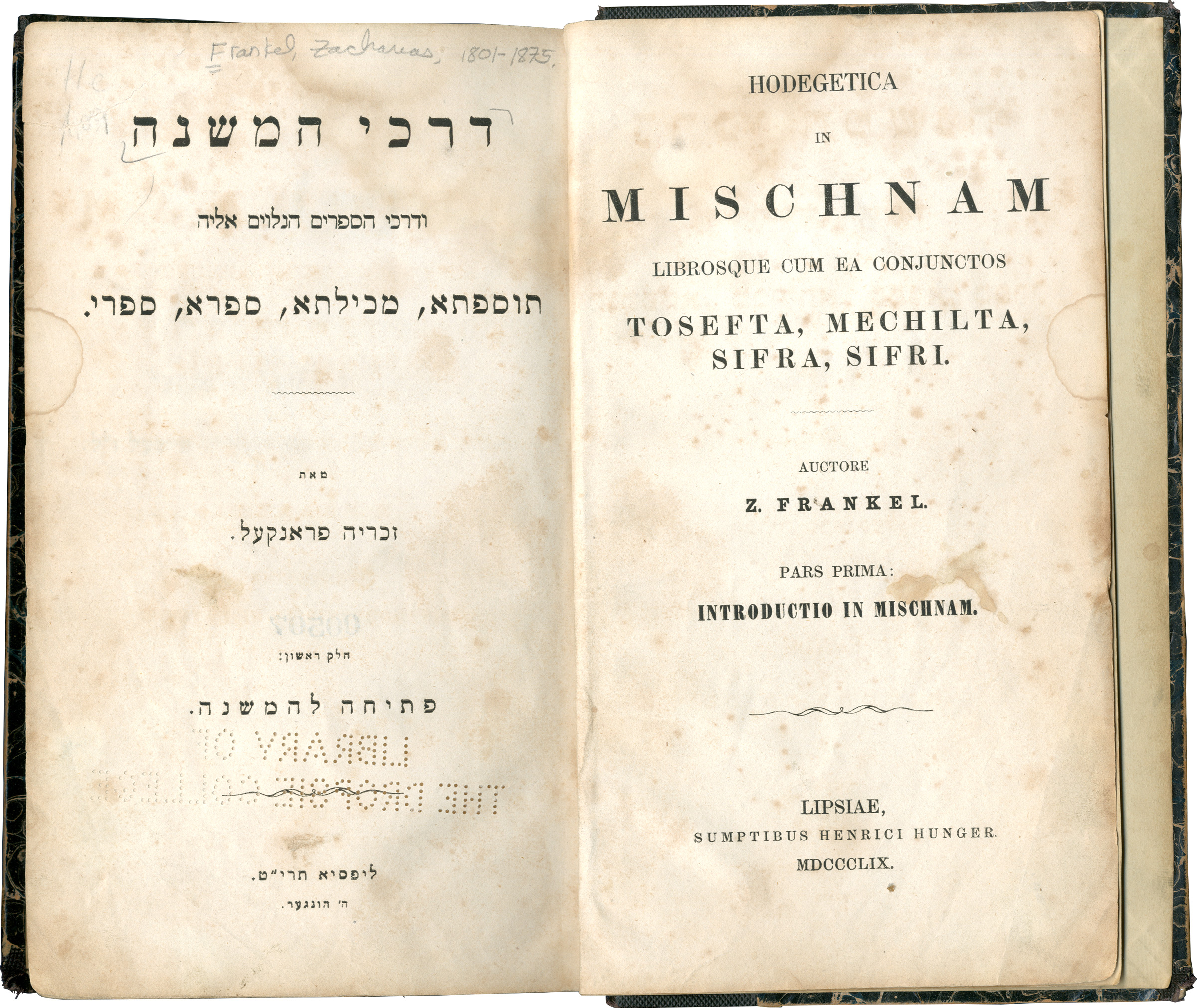

Zacharias Frankel, Darkhe ha-mishnah ve-darkhe ha-sefarim ha-nilvim eleha Tosefta, Mekhilta, Sifra, Sifre. Helek rishon: petihah leha-Mishnah, Leipzig 1859

During the 1850s the religious spectrum of German Jewry encompassed various Orthodox orientations, from an Old Orthodoxy hostile to emancipation and modernity, to a Neo-Orthodoxy that combined a strict Torah-true religious adherence to the Law with an affirmative attitude toward German culture and the German nation. On the other hand, there were radical and moderate versions of a Reform Judaism that looked at tradition through the prism of historical criticism, and evaluated conceptions of faith and its practice using yardsticks calibrated in terms of the cultural and social parameters of the non-Jewish environment. Between Reform Judaism and Orthodoxy, representatives of a third religious current began to distance themselves from Reform and Orthodoxy and express their views in the public arena. Prominent among them was Zacharias Frankel, born in Prague in 1801. After obtaining his doctorate in Budapest in 1830, Frankel was appointed rabbi (Kreisrabbiner) in Leitmeritz (Litoměřice) in Bohemia, before the Dresden Jewish Community elected him as chief rabbi in 1836. In Saxony he served until 1854, establishing a reputation as a "moderate reformer." He then moved to Breslau after having been appointed director of the newly founded Jewish Theological Seminary, the first modern rabbinical training institute on German soil.

As one of the pioneers of modern Wissenschaft des Judentums, Frankel gained fame mainly as a historian of Jewish religious law. In his scholarship he freely adapted concepts originally developed by Friedrich Carl von Savigny and other scholars of the German Historical School of Jurisprudence. In 1859 Heinrich Hunger, a German non Jewish publishing house, seated in Leipzig, printed Frankel’s magnus opum, a scientific introduction to the Mishna. The author initially conceptualized the book as the first part in a series of works dedicated to the history of Tannaitic halakhic literature. However, no further volumes were ever to be published.

Frankel’s book Darkhe ha-mishnah is considered a milestone in modern Jewish scholarship. There also is good reason to call the research he presented "counter-history" because Frankel used key texts of Orthodox Judaism against Orthodoxy in order to corroborate his view of a tradition that had not been revealed at Sinai but developed over the course of history and by that process had gained sacred status. Frankel was severely attacked by conservative religious circles who perceived his introduction as a threat

Celebrating Maimonides’ 800th Birthday in Córdoba

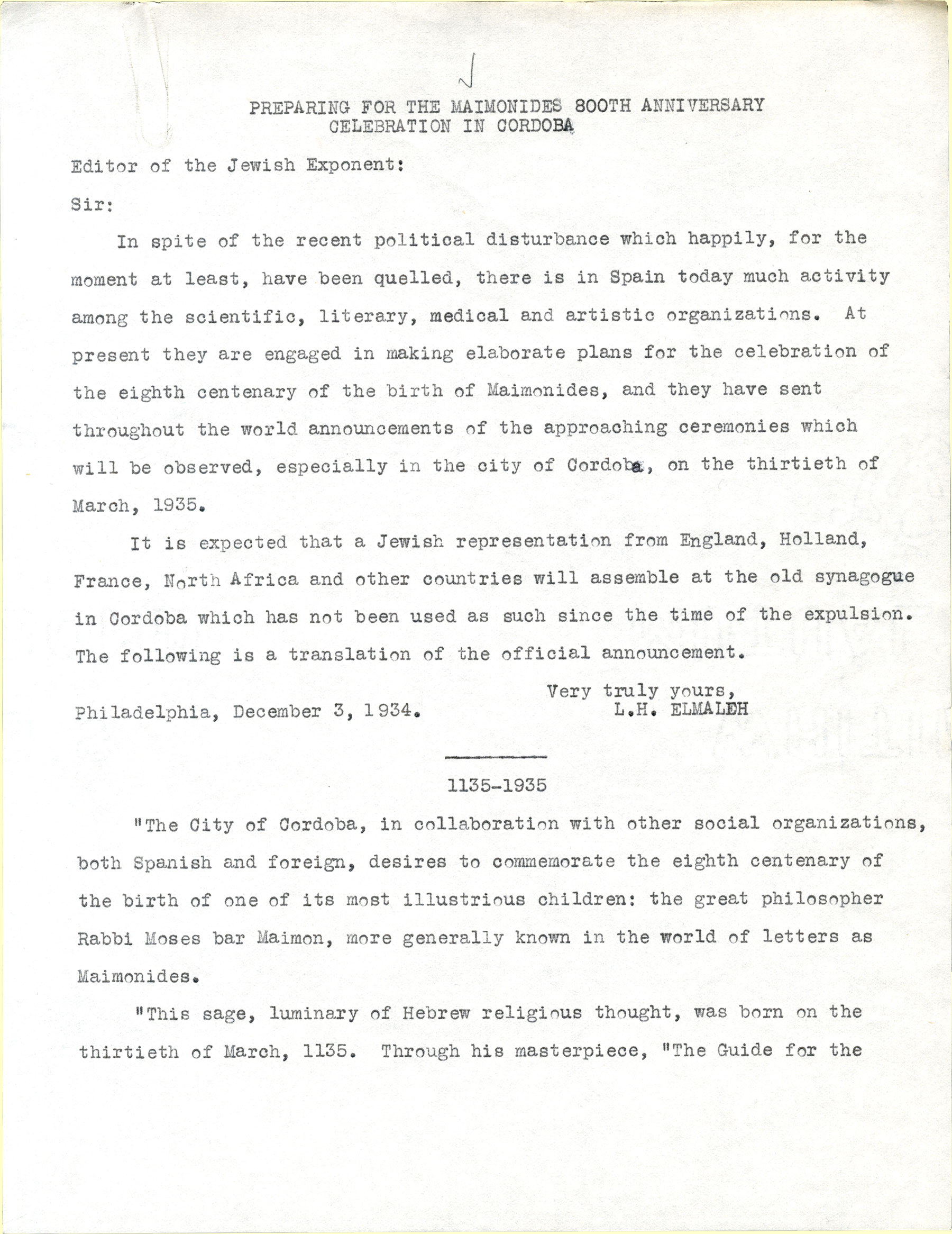

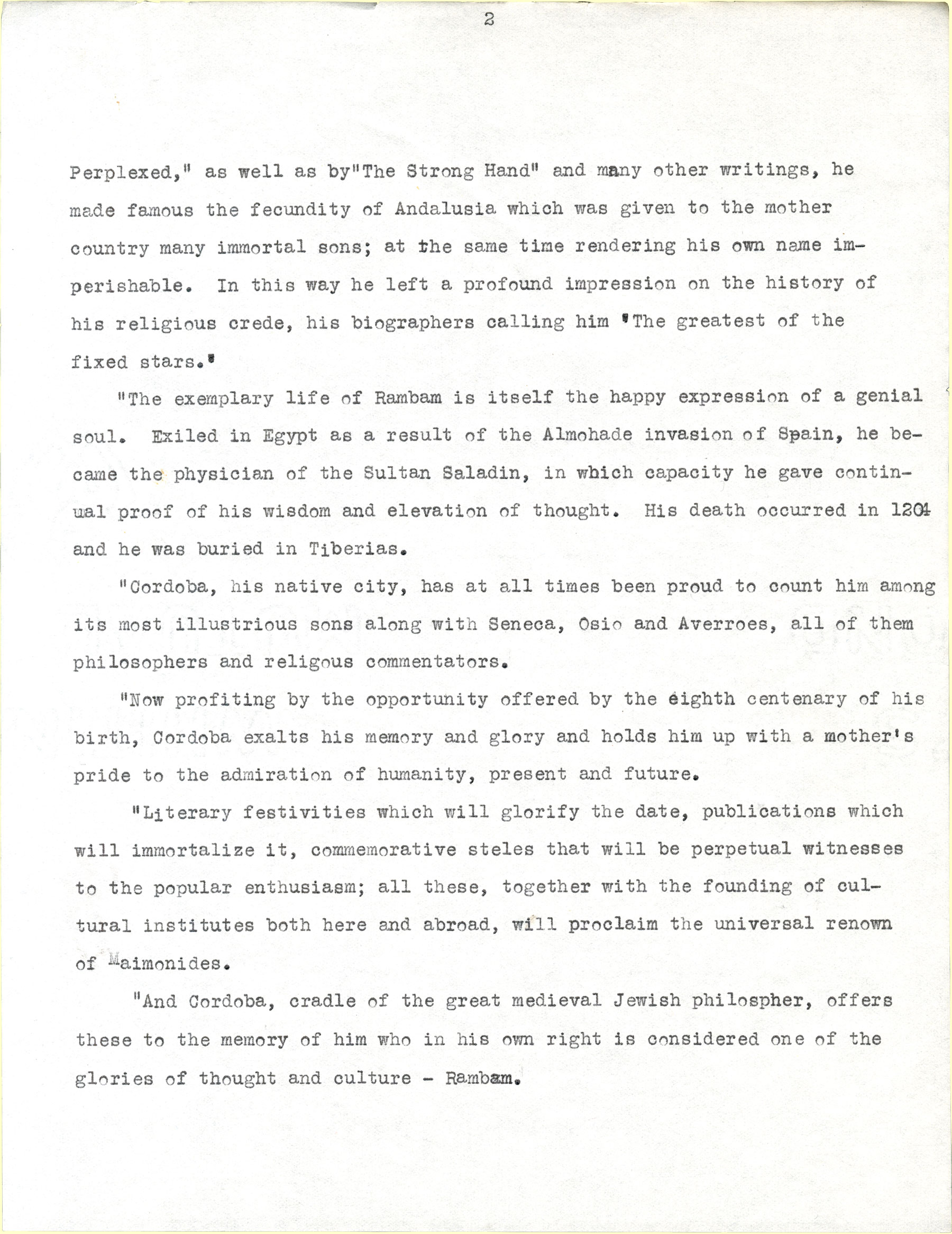

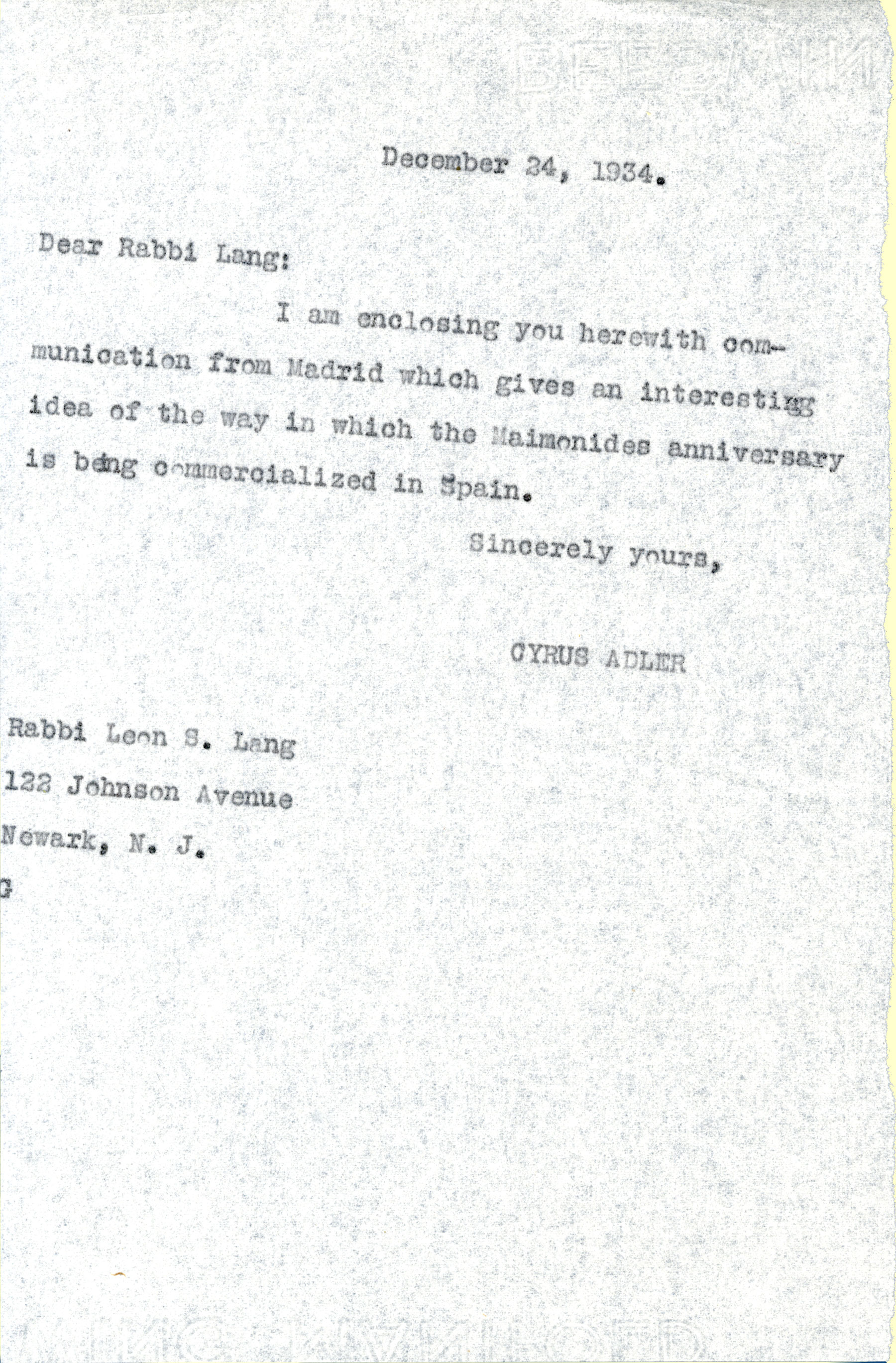

In 1935, elaborate commemorative events took place throughout the world marking the octocentennial of the birth of Maimonides (Rabbi Moses bar Maimon 1135-1204), the medieval Jewish communal leader, philosopher, and physician. With Cyrus Adler at its helm, Dropsie College in Philadelphia took a leading role in the organization of the official commemorative events in the United States. In a letter, dated December 7th, 1934, found in the Adler papers at the Library at the Katz Center, we find Adler being made aware of the planning in Spain, particularly in Maimonides’ native city of Córdoba, for the upcoming celebrations in March of the coming year. The author of the letter, Leon H. Elmaleh, long-time cantor and lecturer at the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, sent Adler under separate cover what he originally wrote to the editor of the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent to inform its readers about the historic recognition by Spain of its ties to the Jewish sage of Córdoba. Elmaleh emphasized the significance of the events and the vitality of the scholarly and professional community in Spain, despite recent, albeit temporarily quelled, political turmoil. Well aware of Dropsie College’s long-standing commitment to Sephardic Studies, Elmaleh most likely forwarded his letter to Adler in the hope he would help disseminate news of the events and perhaps even send a representative to Spain, as Jewish leaders from other nations were planning on attending. Adler indeed immediately sent on the letter to Jewish leaders and sought advice about how to support the Spanish efforts.

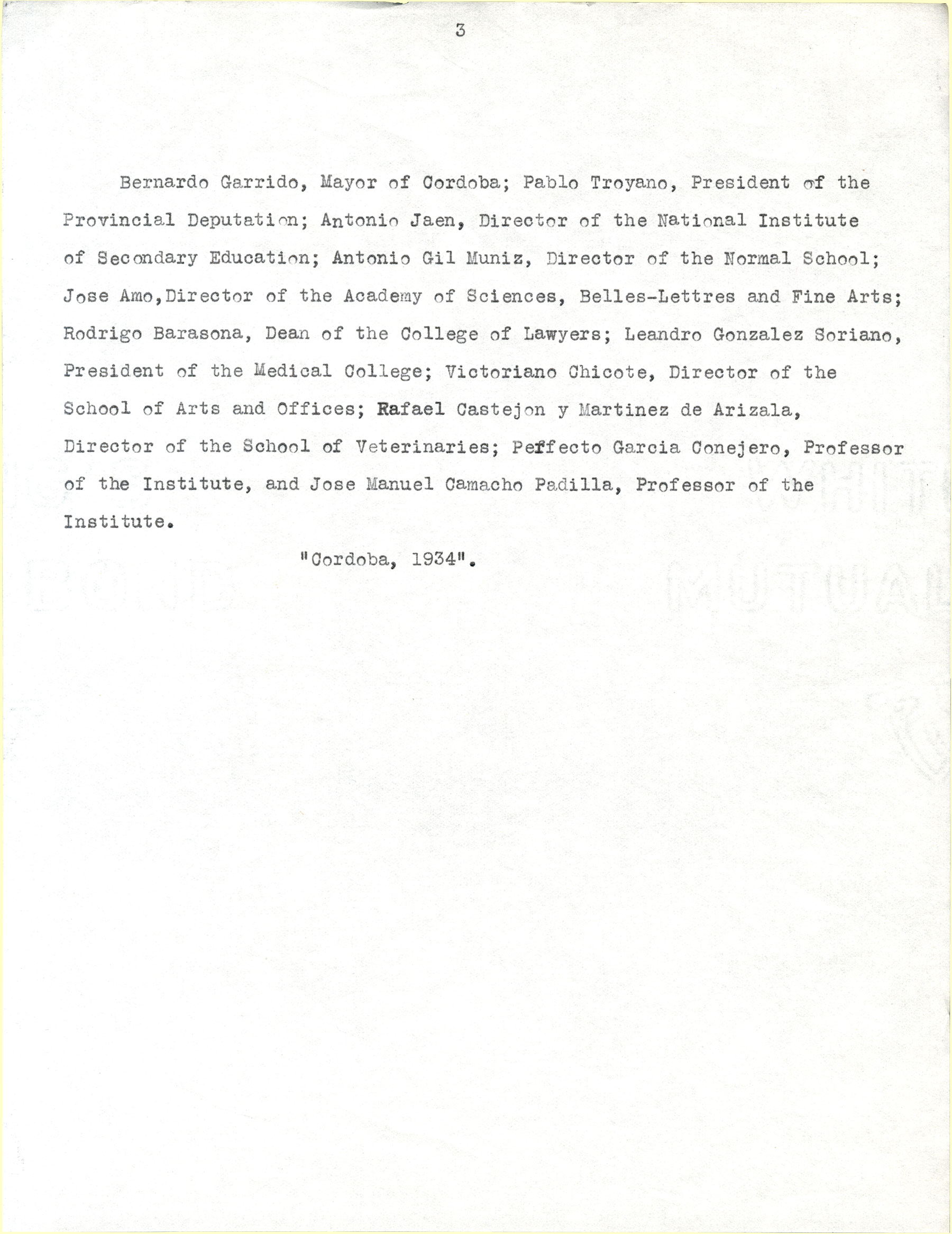

Elmaleh’s letter to Adler also included an English translation of the August 1934 manifesto published by the Royal Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts of Córdoba, in collaboration with the City of Córdoba, and signed by the city’s highest political and academic officials, declaring their intention to commemorate the eighth centennial of the birth of the Cordoban native. The manifesto emphasizes local and regional pride, as it declared Maimonides as “one of its most illustrious sons.” The national government of the Spanish Republic which faced the twin threats of political disintegration and rising fascism soon followed suit by publishing an official decree (on December 8, 1934) signed by Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux, declaring official government sponsorship of the public celebration to take place in Córdoba between March 25 and March 31 of 1935. The commemorative rites in Cordoba thus provided a context for redeeming and reclaiming the Spanish Republic through the re-envisioning of a tolerant transnational and diasporic Spanish patria, specifically through the reintegration of the memory of “Sepharad” and living Sephardim into its fold.

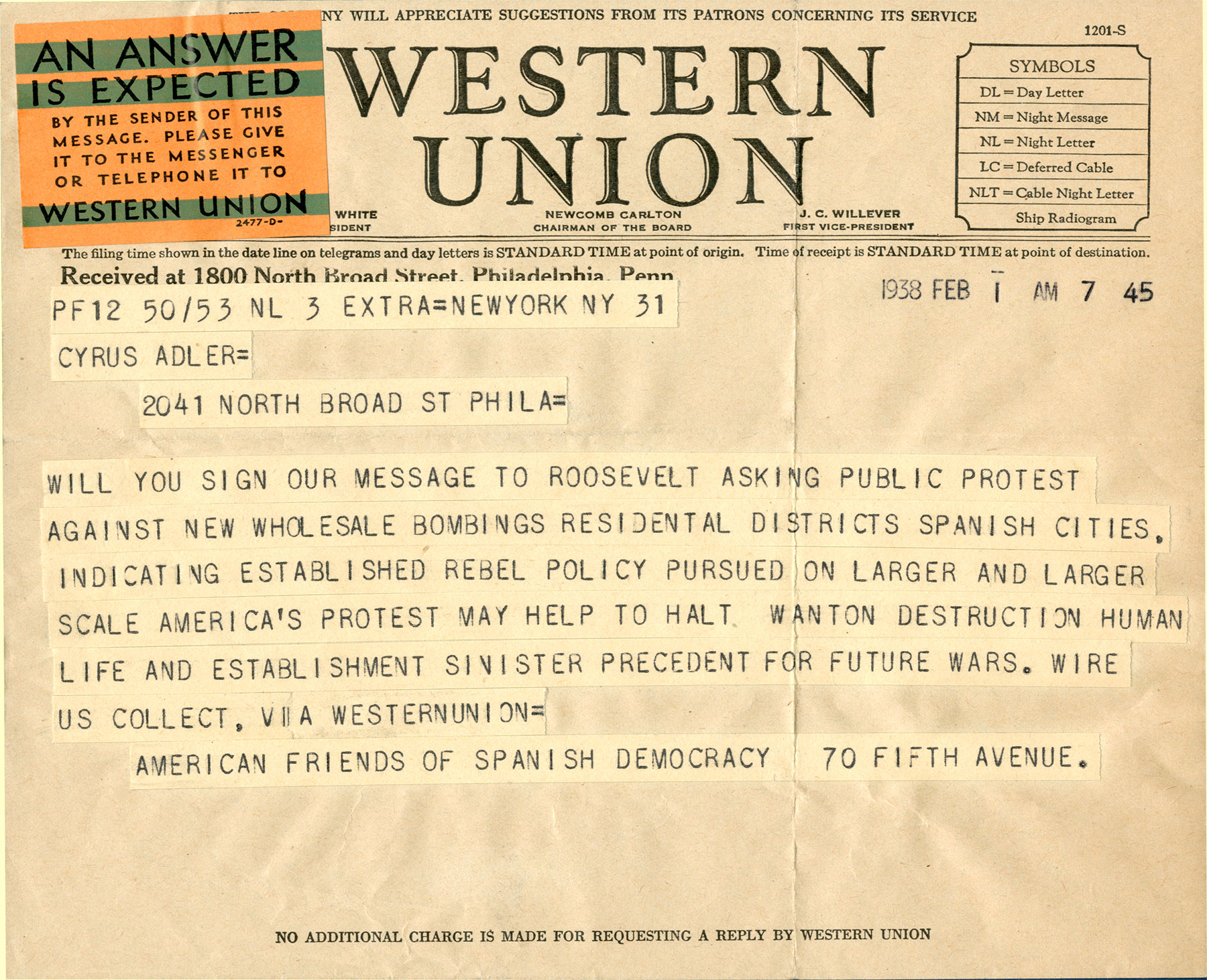

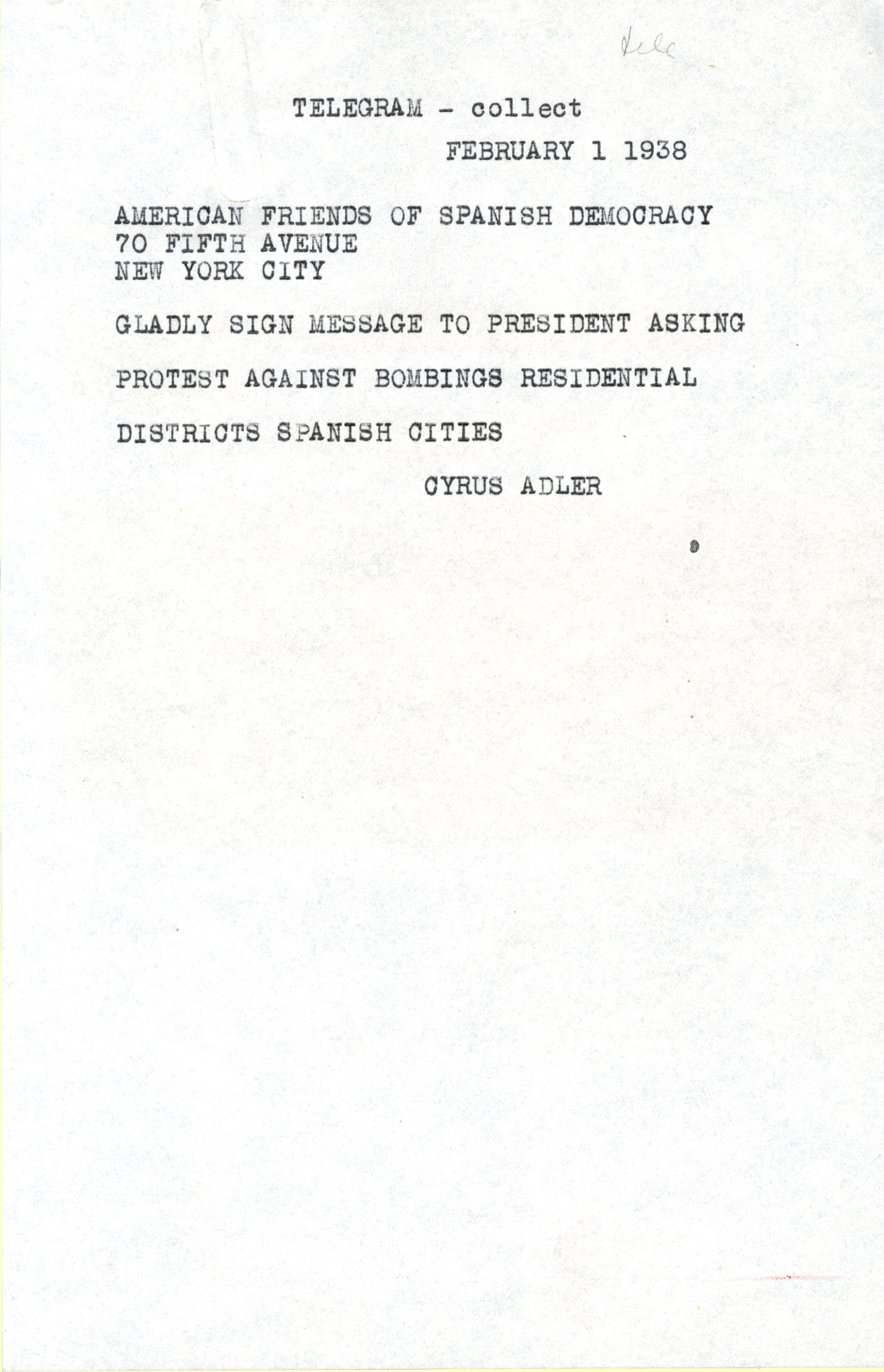

Dropsie College does not seem to have sent a representative to Spain in 1935 and the Republic fell and civil war broke out shortly after the commemoration. Spain nonetheless, came to the attention of Cyrus Adler once again in 1938: On February 1st he received an urgent telegram from “American Friends of Spanish Democracy” asking him to support their message to President Roosevelt supporting public protest against the bombing of residential districts in Spanish cities by the Nationalist rebel faction. In a demonstration of his resounding support for the Spanish Republic, Adler immediately responded by telegram that he would “gladly” sign the message. Adler’s support, as well as the fact that his signature was considered important for this cause (he was also approached by the Abraham Lincoln Brigades and the Social Worker´s Committee to aid Spanish Democracy for Child Welfare) indicates broad public awareness of Adler’s public advocacy on behalf of socially liberal causes, as well as the participation of Jewish leadership in the international fight against fascism. (Cyrus Adler collection “Spain”/Telegram – collect February 1 1938).

Celebrating Maimonides’ 800th Birthday in Córdoba

In 1935, elaborate commemorative events took place throughout the world marking the octocentennial of the birth of Maimonides (Rabbi Moses bar Maimon 1135-1204), the medieval Jewish communal leader, philosopher, and physician. With Cyrus Adler at its helm, Dropsie College in Philadelphia took a leading role in the organization of the official commemorative events in the United States. In a letter, dated December 7th, 1934, found in the Adler papers at the Library at the Katz Center, we find Adler being made aware of the planning in Spain, particularly in Maimonides’ native city of Córdoba, for the upcoming celebrations in March of the coming year. The author of the letter, Leon H. Elmaleh, long-time cantor and lecturer at the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, sent Adler under separate cover what he originally wrote to the editor of the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent to inform its readers about the historic recognition by Spain of its ties to the Jewish sage of Córdoba. Elmaleh emphasized the significance of the events and the vitality of the scholarly and professional community in Spain, despite recent, albeit temporarily quelled, political turmoil. Well aware of Dropsie College’s long-standing commitment to Sephardic Studies, Elmaleh most likely forwarded his letter to Adler in the hope he would help disseminate news of the events and perhaps even send a representative to Spain, as Jewish leaders from other nations were planning on attending. Adler indeed immediately sent on the letter to Jewish leaders and sought advice about how to support the Spanish efforts.

Elmaleh’s letter to Adler also included an English translation of the August 1934 manifesto published by the Royal Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts of Córdoba, in collaboration with the City of Córdoba, and signed by the city’s highest political and academic officials, declaring their intention to commemorate the eighth centennial of the birth of the Cordoban native. The manifesto emphasizes local and regional pride, as it declared Maimonides as “one of its most illustrious sons.” The national government of the Spanish Republic which faced the twin threats of political disintegration and rising fascism soon followed suit by publishing an official decree (on December 8, 1934) signed by Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux, declaring official government sponsorship of the public celebration to take place in Córdoba between March 25 and March 31 of 1935. The commemorative rites in Cordoba thus provided a context for redeeming and reclaiming the Spanish Republic through the re-envisioning of a tolerant transnational and diasporic Spanish patria, specifically through the reintegration of the memory of “Sepharad” and living Sephardim into its fold.

Dropsie College does not seem to have sent a representative to Spain in 1935 and the Republic fell and civil war broke out shortly after the commemoration. Spain nonetheless, came to the attention of Cyrus Adler once again in 1938: On February 1st he received an urgent telegram from “American Friends of Spanish Democracy” asking him to support their message to President Roosevelt supporting public protest against the bombing of residential districts in Spanish cities by the Nationalist rebel faction. In a demonstration of his resounding support for the Spanish Republic, Adler immediately responded by telegram that he would “gladly” sign the message. Adler’s support, as well as the fact that his signature was considered important for this cause (he was also approached by the Abraham Lincoln Brigades and the Social Worker´s Committee to aid Spanish Democracy for Child Welfare) indicates broad public awareness of Adler’s public advocacy on behalf of socially liberal causes, as well as the participation of Jewish leadership in the international fight against fascism. (Cyrus Adler collection “Spain”/Telegram – collect February 1 1938).

Celebrating Maimonides’ 800th Birthday in Córdoba

In 1935, elaborate commemorative events took place throughout the world marking the octocentennial of the birth of Maimonides (Rabbi Moses bar Maimon 1135-1204), the medieval Jewish communal leader, philosopher, and physician. With Cyrus Adler at its helm, Dropsie College in Philadelphia took a leading role in the organization of the official commemorative events in the United States. In a letter, dated December 7th, 1934, found in the Adler papers at the Library at the Katz Center, we find Adler being made aware of the planning in Spain, particularly in Maimonides’ native city of Córdoba, for the upcoming celebrations in March of the coming year. The author of the letter, Leon H. Elmaleh, long-time cantor and lecturer at the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, sent Adler under separate cover what he originally wrote to the editor of the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent to inform its readers about the historic recognition by Spain of its ties to the Jewish sage of Córdoba. Elmaleh emphasized the significance of the events and the vitality of the scholarly and professional community in Spain, despite recent, albeit temporarily quelled, political turmoil. Well aware of Dropsie College’s long-standing commitment to Sephardic Studies, Elmaleh most likely forwarded his letter to Adler in the hope he would help disseminate news of the events and perhaps even send a representative to Spain, as Jewish leaders from other nations were planning on attending. Adler indeed immediately sent on the letter to Jewish leaders and sought advice about how to support the Spanish efforts.

Elmaleh’s letter to Adler also included an English translation of the August 1934 manifesto published by the Royal Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts of Córdoba, in collaboration with the City of Córdoba, and signed by the city’s highest political and academic officials, declaring their intention to commemorate the eighth centennial of the birth of the Cordoban native. The manifesto emphasizes local and regional pride, as it declared Maimonides as “one of its most illustrious sons.” The national government of the Spanish Republic which faced the twin threats of political disintegration and rising fascism soon followed suit by publishing an official decree (on December 8, 1934) signed by Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux, declaring official government sponsorship of the public celebration to take place in Córdoba between March 25 and March 31 of 1935. The commemorative rites in Cordoba thus provided a context for redeeming and reclaiming the Spanish Republic through the re-envisioning of a tolerant transnational and diasporic Spanish patria, specifically through the reintegration of the memory of “Sepharad” and living Sephardim into its fold.

Dropsie College does not seem to have sent a representative to Spain in 1935 and the Republic fell and civil war broke out shortly after the commemoration. Spain nonetheless, came to the attention of Cyrus Adler once again in 1938: On February 1st he received an urgent telegram from “American Friends of Spanish Democracy” asking him to support their message to President Roosevelt supporting public protest against the bombing of residential districts in Spanish cities by the Nationalist rebel faction. In a demonstration of his resounding support for the Spanish Republic, Adler immediately responded by telegram that he would “gladly” sign the message. Adler’s support, as well as the fact that his signature was considered important for this cause (he was also approached by the Abraham Lincoln Brigades and the Social Worker´s Committee to aid Spanish Democracy for Child Welfare) indicates broad public awareness of Adler’s public advocacy on behalf of socially liberal causes, as well as the participation of Jewish leadership in the international fight against fascism. (Cyrus Adler collection “Spain”/Telegram – collect February 1 1938).

Celebrating Maimonides’ 800th Birthday in Córdoba

In 1935, elaborate commemorative events took place throughout the world marking the octocentennial of the birth of Maimonides (Rabbi Moses bar Maimon 1135-1204), the medieval Jewish communal leader, philosopher, and physician. With Cyrus Adler at its helm, Dropsie College in Philadelphia took a leading role in the organization of the official commemorative events in the United States. In a letter, dated December 7th, 1934, found in the Adler papers at the Library at the Katz Center, we find Adler being made aware of the planning in Spain, particularly in Maimonides’ native city of Córdoba, for the upcoming celebrations in March of the coming year. The author of the letter, Leon H. Elmaleh, long-time cantor and lecturer at the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, sent Adler under separate cover what he originally wrote to the editor of the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent to inform its readers about the historic recognition by Spain of its ties to the Jewish sage of Córdoba. Elmaleh emphasized the significance of the events and the vitality of the scholarly and professional community in Spain, despite recent, albeit temporarily quelled, political turmoil. Well aware of Dropsie College’s long-standing commitment to Sephardic Studies, Elmaleh most likely forwarded his letter to Adler in the hope he would help disseminate news of the events and perhaps even send a representative to Spain, as Jewish leaders from other nations were planning on attending. Adler indeed immediately sent on the letter to Jewish leaders and sought advice about how to support the Spanish efforts.

Elmaleh’s letter to Adler also included an English translation of the August 1934 manifesto published by the Royal Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts of Córdoba, in collaboration with the City of Córdoba, and signed by the city’s highest political and academic officials, declaring their intention to commemorate the eighth centennial of the birth of the Cordoban native. The manifesto emphasizes local and regional pride, as it declared Maimonides as “one of its most illustrious sons.” The national government of the Spanish Republic which faced the twin threats of political disintegration and rising fascism soon followed suit by publishing an official decree (on December 8, 1934) signed by Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux, declaring official government sponsorship of the public celebration to take place in Córdoba between March 25 and March 31 of 1935. The commemorative rites in Cordoba thus provided a context for redeeming and reclaiming the Spanish Republic through the re-envisioning of a tolerant transnational and diasporic Spanish patria, specifically through the reintegration of the memory of “Sepharad” and living Sephardim into its fold.

Dropsie College does not seem to have sent a representative to Spain in 1935 and the Republic fell and civil war broke out shortly after the commemoration. Spain nonetheless, came to the attention of Cyrus Adler once again in 1938: On February 1st he received an urgent telegram from “American Friends of Spanish Democracy” asking him to support their message to President Roosevelt supporting public protest against the bombing of residential districts in Spanish cities by the Nationalist rebel faction. In a demonstration of his resounding support for the Spanish Republic, Adler immediately responded by telegram that he would “gladly” sign the message. Adler’s support, as well as the fact that his signature was considered important for this cause (he was also approached by the Abraham Lincoln Brigades and the Social Worker´s Committee to aid Spanish Democracy for Child Welfare) indicates broad public awareness of Adler’s public advocacy on behalf of socially liberal causes, as well as the participation of Jewish leadership in the international fight against fascism. (Cyrus Adler collection “Spain”/Telegram – collect February 1 1938).

Celebrating Maimonides’ 800th Birthday in Córdoba

In 1935, elaborate commemorative events took place throughout the world marking the octocentennial of the birth of Maimonides (Rabbi Moses bar Maimon 1135-1204), the medieval Jewish communal leader, philosopher, and physician. With Cyrus Adler at its helm, Dropsie College in Philadelphia took a leading role in the organization of the official commemorative events in the United States. In a letter, dated December 7th, 1934, found in the Adler papers at the Library at the Katz Center, we find Adler being made aware of the planning in Spain, particularly in Maimonides’ native city of Córdoba, for the upcoming celebrations in March of the coming year. The author of the letter, Leon H. Elmaleh, long-time cantor and lecturer at the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, sent Adler under separate cover what he originally wrote to the editor of the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent to inform its readers about the historic recognition by Spain of its ties to the Jewish sage of Córdoba. Elmaleh emphasized the significance of the events and the vitality of the scholarly and professional community in Spain, despite recent, albeit temporarily quelled, political turmoil. Well aware of Dropsie College’s long-standing commitment to Sephardic Studies, Elmaleh most likely forwarded his letter to Adler in the hope he would help disseminate news of the events and perhaps even send a representative to Spain, as Jewish leaders from other nations were planning on attending. Adler indeed immediately sent on the letter to Jewish leaders and sought advice about how to support the Spanish efforts.

Elmaleh’s letter to Adler also included an English translation of the August 1934 manifesto published by the Royal Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts of Córdoba, in collaboration with the City of Córdoba, and signed by the city’s highest political and academic officials, declaring their intention to commemorate the eighth centennial of the birth of the Cordoban native. The manifesto emphasizes local and regional pride, as it declared Maimonides as “one of its most illustrious sons.” The national government of the Spanish Republic which faced the twin threats of political disintegration and rising fascism soon followed suit by publishing an official decree (on December 8, 1934) signed by Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux, declaring official government sponsorship of the public celebration to take place in Córdoba between March 25 and March 31 of 1935. The commemorative rites in Cordoba thus provided a context for redeeming and reclaiming the Spanish Republic through the re-envisioning of a tolerant transnational and diasporic Spanish patria, specifically through the reintegration of the memory of “Sepharad” and living Sephardim into its fold.

Dropsie College does not seem to have sent a representative to Spain in 1935 and the Republic fell and civil war broke out shortly after the commemoration. Spain nonetheless, came to the attention of Cyrus Adler once again in 1938: On February 1st he received an urgent telegram from “American Friends of Spanish Democracy” asking him to support their message to President Roosevelt supporting public protest against the bombing of residential districts in Spanish cities by the Nationalist rebel faction. In a demonstration of his resounding support for the Spanish Republic, Adler immediately responded by telegram that he would “gladly” sign the message. Adler’s support, as well as the fact that his signature was considered important for this cause (he was also approached by the Abraham Lincoln Brigades and the Social Worker´s Committee to aid Spanish Democracy for Child Welfare) indicates broad public awareness of Adler’s public advocacy on behalf of socially liberal causes, as well as the participation of Jewish leadership in the international fight against fascism. (Cyrus Adler collection “Spain”/Telegram – collect February 1 1938).

Celebrating Maimonides’ 800th Birthday in Córdoba

In 1935, elaborate commemorative events took place throughout the world marking the octocentennial of the birth of Maimonides (Rabbi Moses bar Maimon 1135-1204), the medieval Jewish communal leader, philosopher, and physician. With Cyrus Adler at its helm, Dropsie College in Philadelphia took a leading role in the organization of the official commemorative events in the United States. In a letter, dated December 7th, 1934, found in the Adler papers at the Library at the Katz Center, we find Adler being made aware of the planning in Spain, particularly in Maimonides’ native city of Córdoba, for the upcoming celebrations in March of the coming year. The author of the letter, Leon H. Elmaleh, long-time cantor and lecturer at the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, sent Adler under separate cover what he originally wrote to the editor of the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent to inform its readers about the historic recognition by Spain of its ties to the Jewish sage of Córdoba. Elmaleh emphasized the significance of the events and the vitality of the scholarly and professional community in Spain, despite recent, albeit temporarily quelled, political turmoil. Well aware of Dropsie College’s long-standing commitment to Sephardic Studies, Elmaleh most likely forwarded his letter to Adler in the hope he would help disseminate news of the events and perhaps even send a representative to Spain, as Jewish leaders from other nations were planning on attending. Adler indeed immediately sent on the letter to Jewish leaders and sought advice about how to support the Spanish efforts.

Elmaleh’s letter to Adler also included an English translation of the August 1934 manifesto published by the Royal Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts of Córdoba, in collaboration with the City of Córdoba, and signed by the city’s highest political and academic officials, declaring their intention to commemorate the eighth centennial of the birth of the Cordoban native. The manifesto emphasizes local and regional pride, as it declared Maimonides as “one of its most illustrious sons.” The national government of the Spanish Republic which faced the twin threats of political disintegration and rising fascism soon followed suit by publishing an official decree (on December 8, 1934) signed by Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux, declaring official government sponsorship of the public celebration to take place in Córdoba between March 25 and March 31 of 1935. The commemorative rites in Cordoba thus provided a context for redeeming and reclaiming the Spanish Republic through the re-envisioning of a tolerant transnational and diasporic Spanish patria, specifically through the reintegration of the memory of “Sepharad” and living Sephardim into its fold.

Dropsie College does not seem to have sent a representative to Spain in 1935 and the Republic fell and civil war broke out shortly after the commemoration. Spain nonetheless, came to the attention of Cyrus Adler once again in 1938: On February 1st he received an urgent telegram from “American Friends of Spanish Democracy” asking him to support their message to President Roosevelt supporting public protest against the bombing of residential districts in Spanish cities by the Nationalist rebel faction. In a demonstration of his resounding support for the Spanish Republic, Adler immediately responded by telegram that he would “gladly” sign the message. Adler’s support, as well as the fact that his signature was considered important for this cause (he was also approached by the Abraham Lincoln Brigades and the Social Worker´s Committee to aid Spanish Democracy for Child Welfare) indicates broad public awareness of Adler’s public advocacy on behalf of socially liberal causes, as well as the participation of Jewish leadership in the international fight against fascism. (Cyrus Adler collection “Spain”/Telegram – collect February 1 1938).

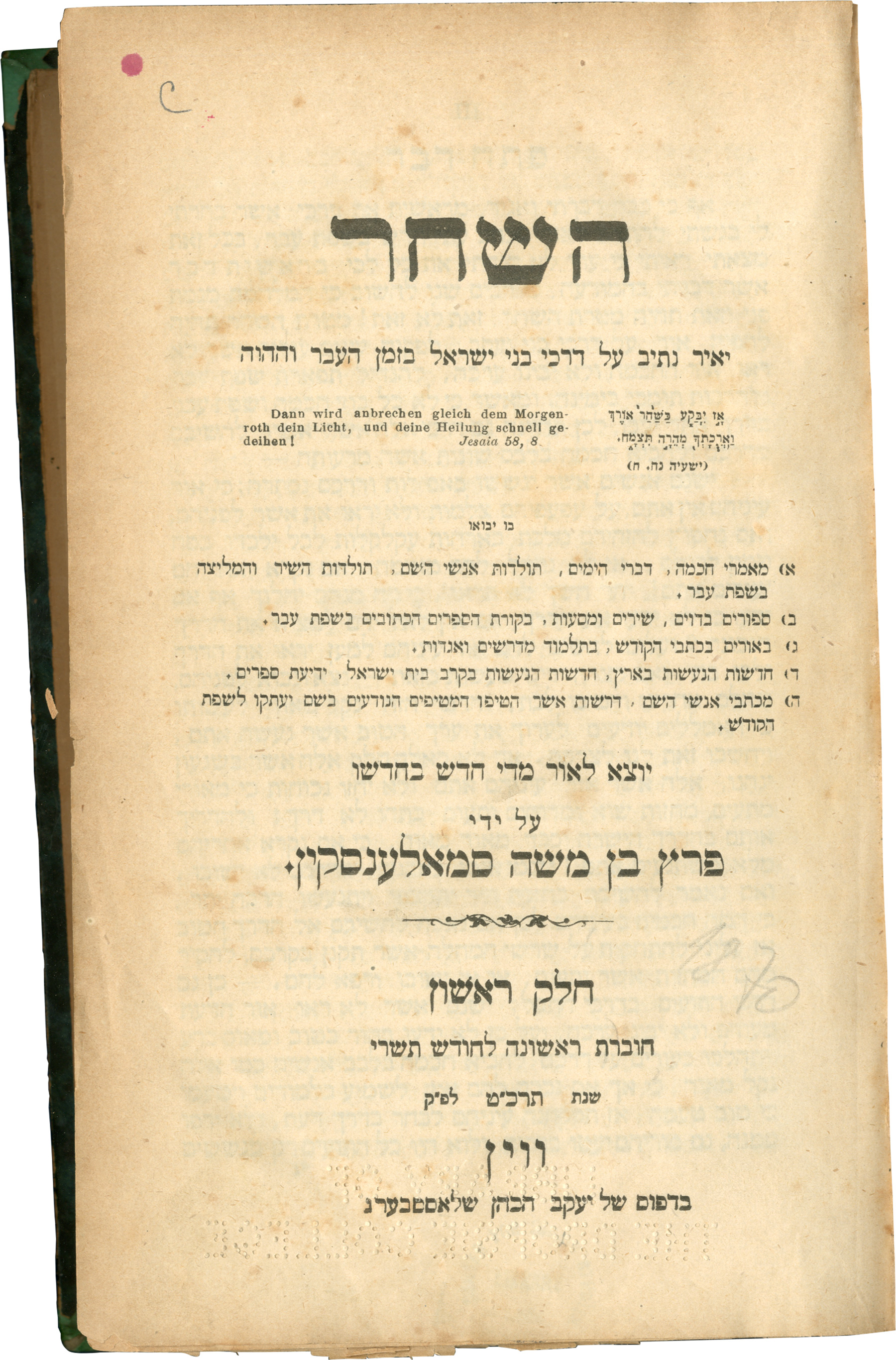

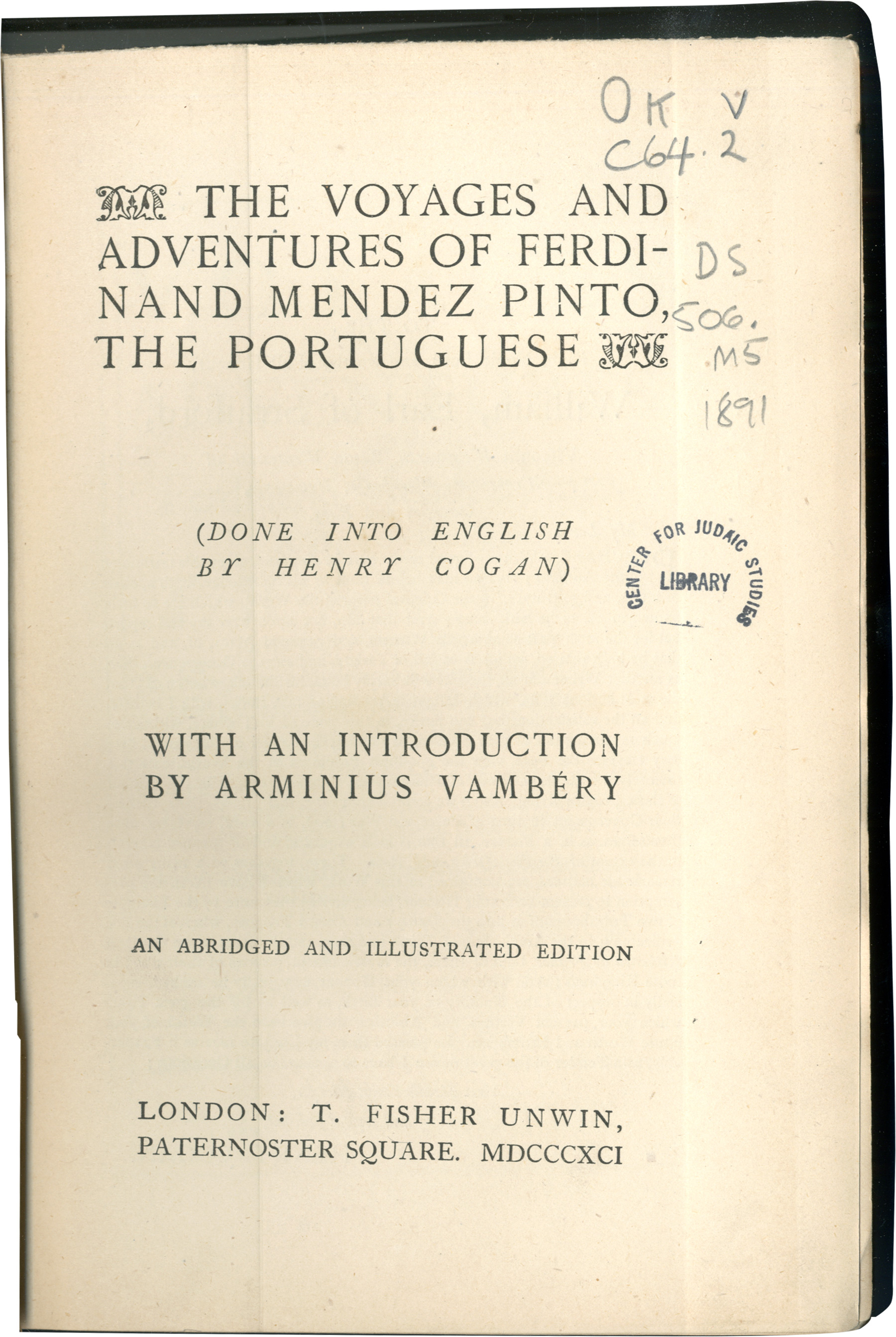

Ha-Shahar

Ha-Shahar was a Hebrew monthly periodical published in Vienna (1868-1884). The editor and publisher Peretz Smolenskin (1842-1885) dedicated the journal to Hebrew literature and Judaic studies (Chochmat Israel). The significance of the journal's title and subtitle, Ha-Shahar (The Dawn): will illuminate the path of the children of Israel in the past and in the present is explained in the Opening Manifesto (volume 1, III-VI) in which the editor expressed the distinct enlightened-national viewpoint of the journal. The use of the Hebrew language for Jewish science, literature and poetry was a clear ideological manifestation of this outlook and a vehicle for promoting Jewish cultural nationalism. In the twelve volumes of Ha-Shahar we find the publications of entire novels by Smolenskin himself along with novels of other Hebrew writers of the era. Most of the Hebrew poets of the time contributed regularly to Ha-Shahar, among them Yehuda Leib Gordon (YaLaG). A prominent part of the journal was dedicated to scholarly works of Judaic Studies, historiographic articles and book critics. Therefore Ha-Shahar was a pioneering journal, not only for the Hebrew Haskalah literature, but also in the national version of Jewish studies in the Hebrew language.

Ha-Shahar

Ha-Shahar was a Hebrew monthly periodical published in Vienna (1868-1884). The editor and publisher Peretz Smolenskin (1842-1885) dedicated the journal to Hebrew literature and Judaic studies (Chochmat Israel). The significance of the journal's title and subtitle, Ha-Shahar (The Dawn): will illuminate the path of the children of Israel in the past and in the present is explained in the Opening Manifesto (volume 1, III-VI) in which the editor expressed the distinct enlightened-national viewpoint of the journal. The use of the Hebrew language for Jewish science, literature and poetry was a clear ideological manifestation of this outlook and a vehicle for promoting Jewish cultural nationalism. In the twelve volumes of Ha-Shahar we find the publications of entire novels by Smolenskin himself along with novels of other Hebrew writers of the era. Most of the Hebrew poets of the time contributed regularly to Ha-Shahar, among them Yehuda Leib Gordon (YaLaG). A prominent part of the journal was dedicated to scholarly works of Judaic Studies, historiographic articles and book critics. Therefore Ha-Shahar was a pioneering journal, not only for the Hebrew Haskalah literature, but also in the national version of Jewish studies in the Hebrew language.

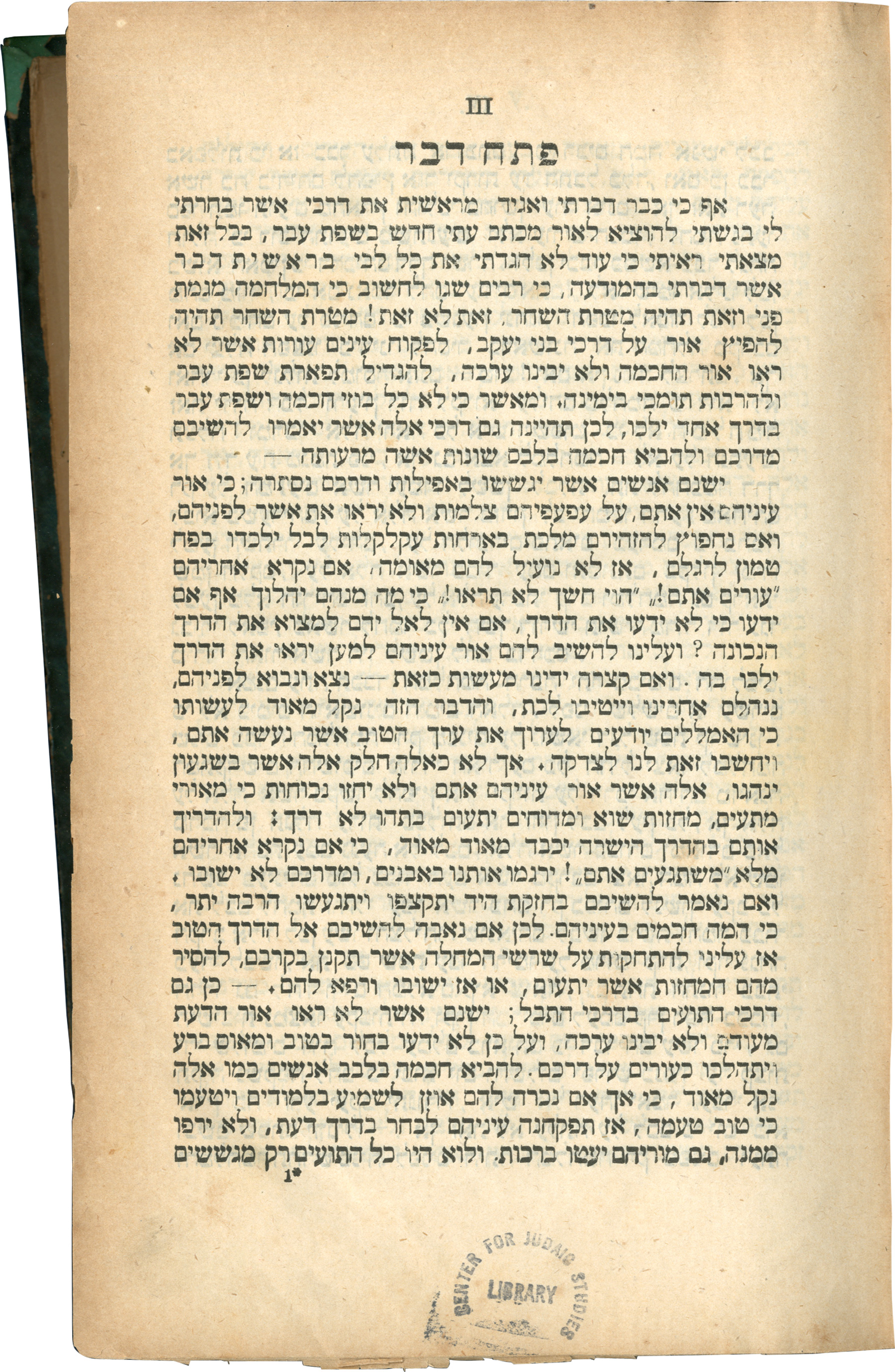

Gotthard Deutsch and the updating of Wissenschaft des Judentums in the United States

The need to update historical study is generally recognized as essential to the progress of Wissenschaft des Judentums, the modern critical approach to Judaism. New questions arise, new sources are discovered, and conclusions reached in recent books and articles augment and alter what is contained in standard works. Gotthard Deutsch (1859-1921) was a German-trained Jewish historian who taught at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati beginning in 1891. He had been a student of the greatest Jewish historian of the nineteenth century, Heinrich Graetz (1817-1891), and owned a set of his multi-volume Geschichte der Juden. However, Deutsch realized that if he were to become a successor to Graetz, he had to update Graetz's work with the multiple new facts that had become known since Graetz published his history. So whenever Deutsch encountered a significant new source or study, he inscribed its essence into his interleaved copy of the relevant Graetz volume. For example, when Ludwig Geiger published a history of the Berlin Jewish community with passages relevant to the Reform movement, Deutsch added material from Geiger to update Graetz on the blank page opposite his treatment of the first permanent Reform synagogue, the Hamburg Temple.

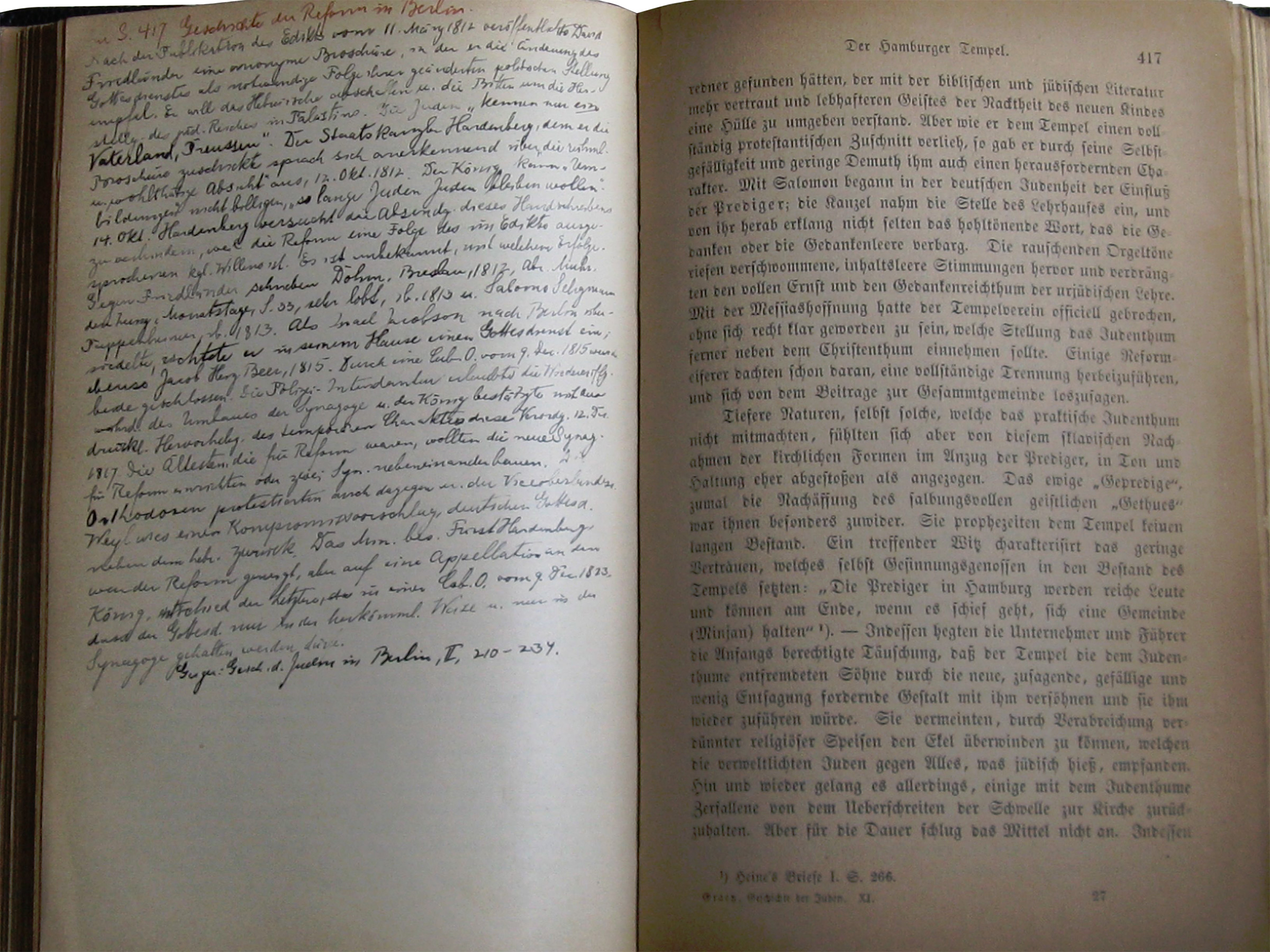

Mendez Pinto's Travels and Oriental Scholarship

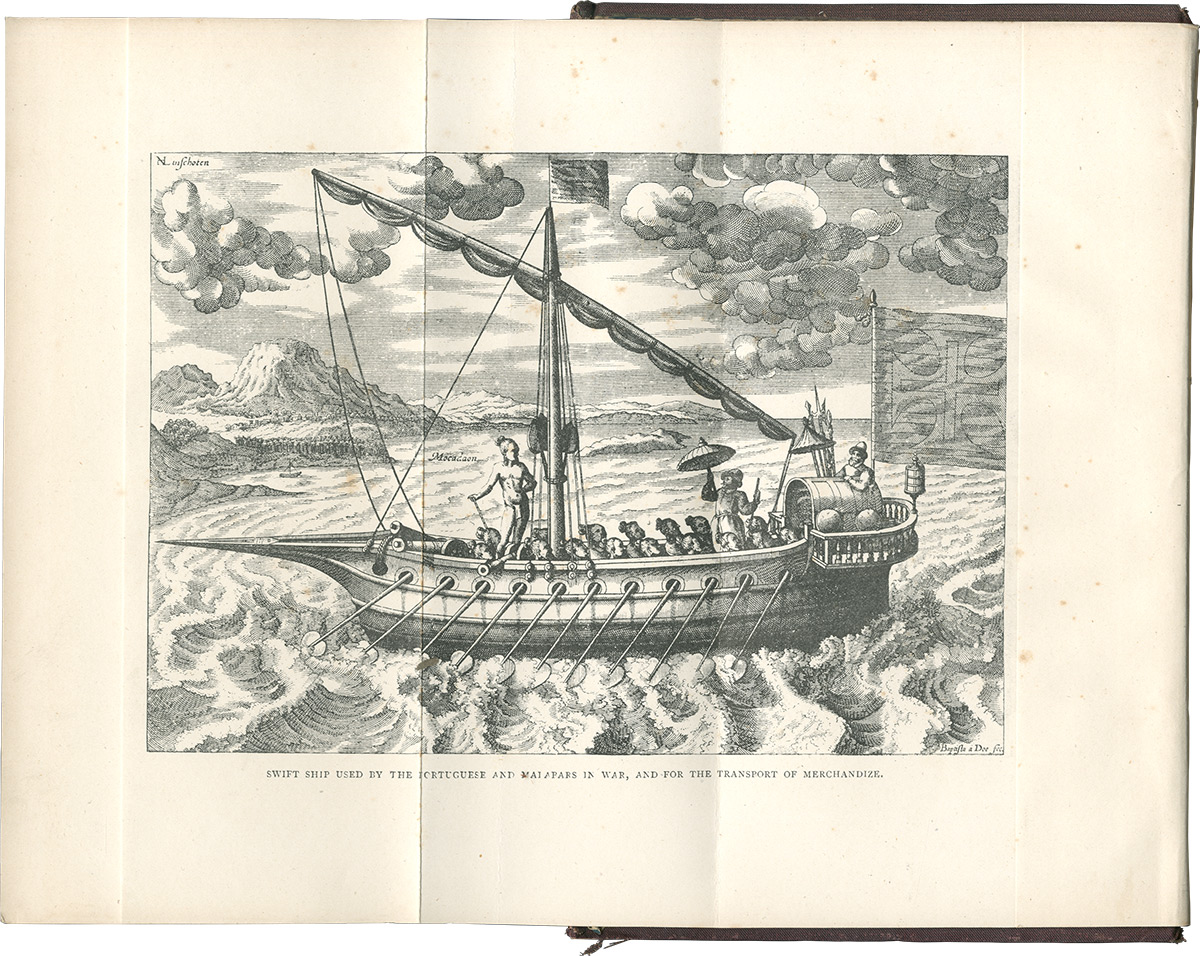

The Voyages and Adventures of Ferdinand Mendez Pinto, the Portuguese is one of the best-known travelogues of all time. Pinto (who died in 1583) was the first European who described in writing what he saw and experienced during his travels in South East Asia. His manuscript was printed not only in the original Portuguese; the English edition in Henry Cogan's translation was published in London in 1663 and over the centuries several other translations and editions saw light. The Library at the Katz Center holds the 1897 English edition, which is an abridged version of the original Cogan translation and includes an introduction by the Hungarian Jewish orientalist Armin Vambery. Vambery, a self-taught Turkologist, traveler, and popular author of travelogues, stressed the importance of Pinto's book in advancing European knowledge about Asia in the early modern period. He also emphasized the saliency of travel in modern Oriental scholarship. His introduction illustrates that nineteenth-century orientalists believed that traveling complemented philological, archeological, and historical research. Like Pinto and Vambery, they wrote travelogues to inform readers about their experiences in far-away lands, educate European audiences about distant cultures, and, consequently, to popularize their scholarship. Publishing travelogues ensured a steady income, which allowed them to continue their scholarly research. In addition, for Jewish scholars like Vambery, the publication of travelogues and shorter reports about the Orient was an important means to claim membership in the modern European public sphere and demonstrate that not only fellow academics, but also the broader public found their research interesting.

Mendez Pinto's Travels and Oriental Scholarship

The Voyages and Adventures of Ferdinand Mendez Pinto, the Portuguese is one of the best-known travelogues of all time. Pinto (who died in 1583) was the first European who described in writing what he saw and experienced during his travels in South East Asia. His manuscript was printed not only in the original Portuguese; the English edition in Henry Cogan's translation was published in London in 1663 and over the centuries several other translations and editions saw light. The Library at the Katz Center holds the 1897 English edition, which is an abridged version of the original Cogan translation and includes an introduction by the Hungarian Jewish orientalist Armin Vambery. Vambery, a self-taught Turkologist, traveler, and popular author of travelogues, stressed the importance of Pinto's book in advancing European knowledge about Asia in the early modern period. He also emphasized the saliency of travel in modern Oriental scholarship. His introduction illustrates that nineteenth-century orientalists believed that traveling complemented philological, archeological, and historical research. Like Pinto and Vambery, they wrote travelogues to inform readers about their experiences in far-away lands, educate European audiences about distant cultures, and, consequently, to popularize their scholarship. Publishing travelogues ensured a steady income, which allowed them to continue their scholarly research. In addition, for Jewish scholars like Vambery, the publication of travelogues and shorter reports about the Orient was an important means to claim membership in the modern European public sphere and demonstrate that not only fellow academics, but also the broader public found their research interesting.

Religious Reform in 19th Century Italy: Calls to Abolish Circumcision and Metsitsah be-peh

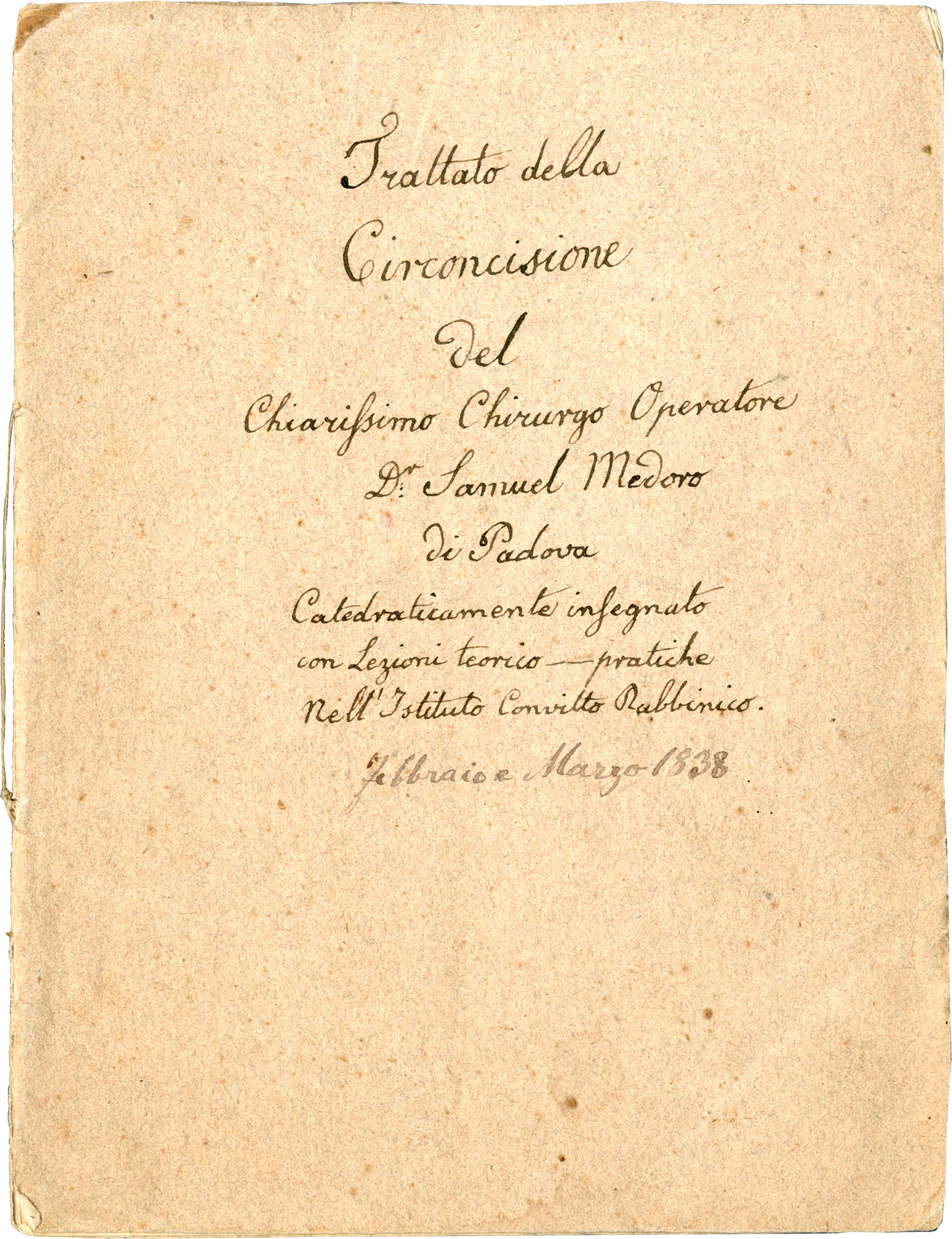

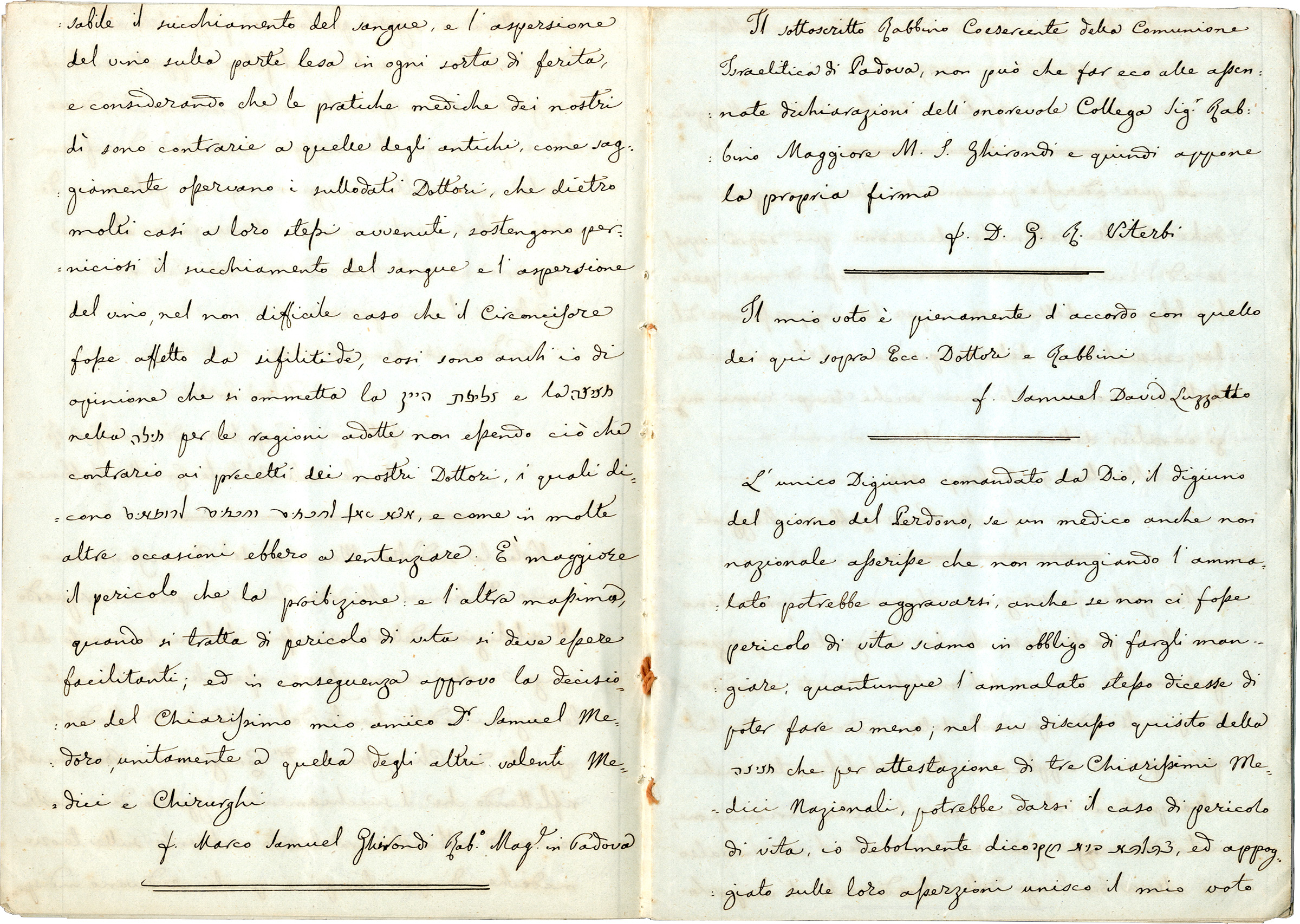

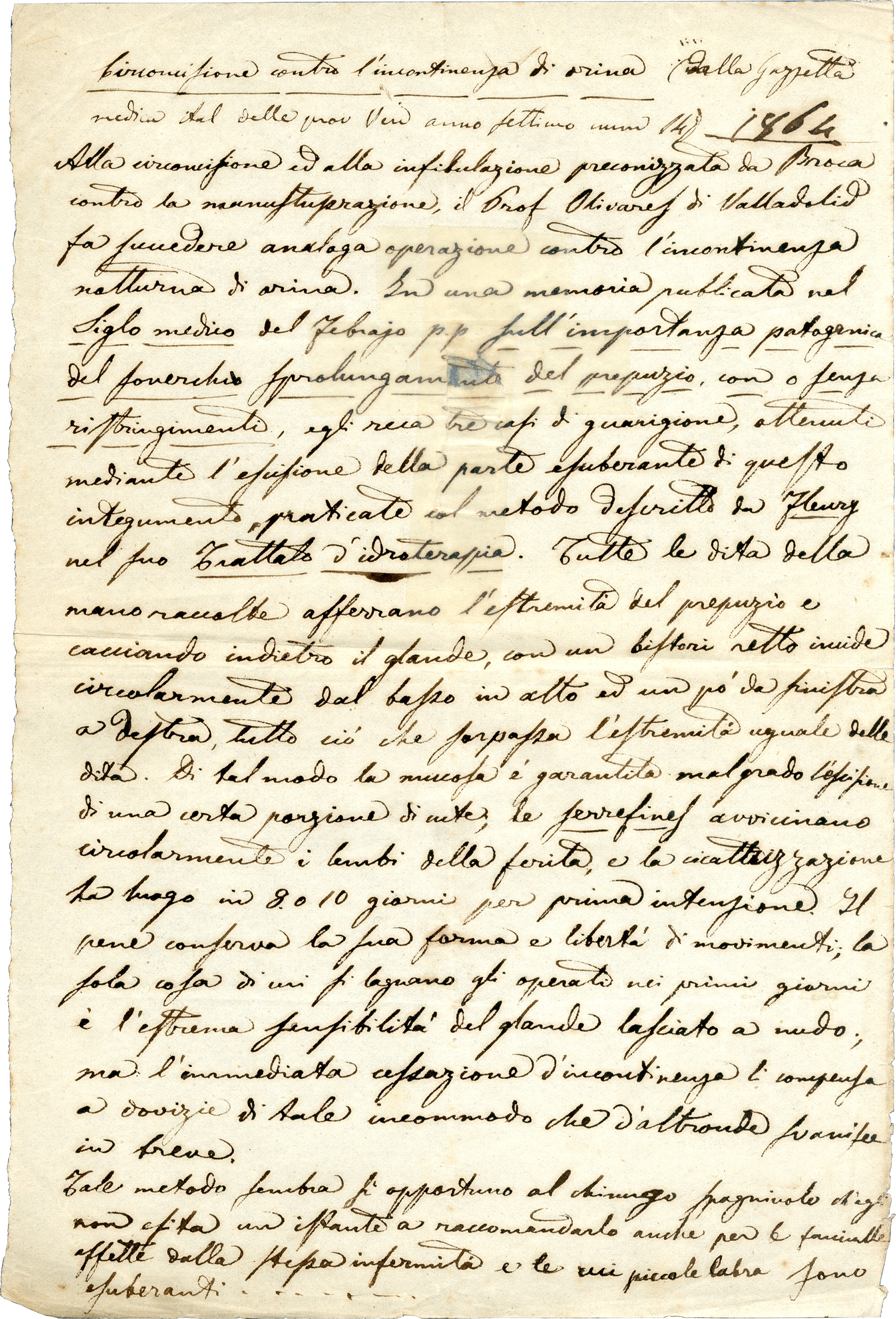

Depicted here (left, top) is the frontispiece of a small notebook containing a handwritten text conceived for a course held in the month of February and March, 1838, at the Rabbinical Seminary of Padua by the renowned physician Dr. Samuel Medoro (1788-1854). In his lessons concerning the performance of circumcision, Dr. Medoro supports the abolishment of metsitsah be-peh (sucking by mouth the blood from the wound) from a medical as well as from a social standpoint, not only because it can endanger the newborn's health but also because he deems it to be indecorous. Moreover, his booklet reveals a tight cooperation between the students and appointed teachers at the rabbinical seminar of Padua

But perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the bundle of documents purchased by the Penn Libraries at auction in Israel in 2012 is the copies of the responsa of fourteen rabbis written in Italian between November 18th, 1847, and May 6th, 1852, plus a page with excerpts from an article published in the Gazzetta Medica Italiana

Religious Reform in 19th Century Italy: Calls to Abolish Circumcision and Metsitsah be-peh

Depicted here (left, top) is the frontispiece of a small notebook containing a handwritten text conceived for a course held in the month of February and March, 1838, at the Rabbinical Seminary of Padua by the renowned physician Dr. Samuel Medoro (1788-1854). In his lessons concerning the performance of circumcision, Dr. Medoro supports the abolishment of metsitsah be-peh (sucking by mouth the blood from the wound) from a medical as well as from a social standpoint, not only because it can endanger the newborn's health but also because he deems it to be indecorous. Moreover, his booklet reveals a tight cooperation between the students and appointed teachers at the rabbinical seminar of Padua

But perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the bundle of documents purchased by the Penn Libraries at auction in Israel in 2012 is the copies of the responsa of fourteen rabbis written in Italian between November 18th, 1847, and May 6th, 1852, plus a page with excerpts from an article published in the Gazzetta Medica Italiana

Religious Reform in 19th Century Italy: Calls to Abolish Circumcision and Metsitsah be-peh

Depicted here (left, top) is the frontispiece of a small notebook containing a handwritten text conceived for a course held in the month of February and March, 1838, at the Rabbinical Seminary of Padua by the renowned physician Dr. Samuel Medoro (1788-1854). In his lessons concerning the performance of circumcision, Dr. Medoro supports the abolishment of metsitsah be-peh (sucking by mouth the blood from the wound) from a medical as well as from a social standpoint, not only because it can endanger the newborn's health but also because he deems it to be indecorous. Moreover, his booklet reveals a tight cooperation between the students and appointed teachers at the rabbinical seminar of Padua

But perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the bundle of documents purchased by the Penn Libraries at auction in Israel in 2012 is the copies of the responsa of fourteen rabbis written in Italian between November 18th, 1847, and May 6th, 1852, plus a page with excerpts from an article published in the Gazzetta Medica Italiana

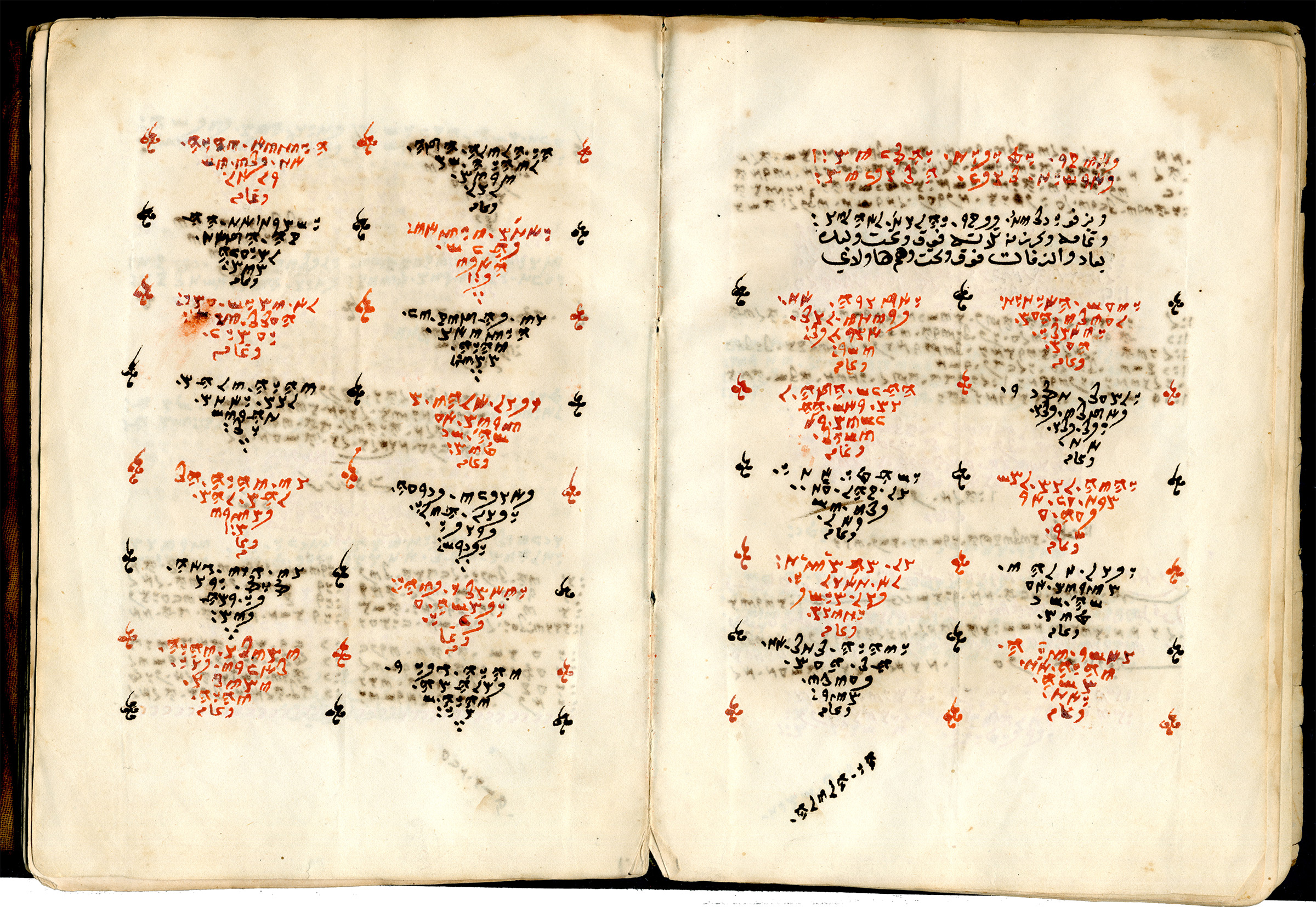

Sources for Study: The Ancient Samaritan Community

The Samaritans, an offspring of the tradition of Ancient Israel, became independent from the Jewish tradition in the 2nd century BCE. A main point of difference between Jews and Samaritans has been the question of the central holy place, which according to the Samaritan beliefs is not found in Jerusalem, but on Mount Gerizim in the vicinity of Nablus, or the Biblical city of Shechem.

Although their sanctuary on Mount Gerizim was destroyed in 128 BCE, the Samaritans have continued to celebrate the yearly Passover sacrifice in accordance with the Biblical text of Exodus 12. The present manuscript from the collections of the Katz Center [CAJS Rar Ms 104, 31v-32r], a booklet with 190 pages, contains the festival liturgy for this holiday with prayers in Samaritan Aramaic and Hebrew, and with commentaries and explanations in Arabic. It was written in 1844, at a time when the Samaritan holy places on the summit of the mountain were generally inaccessible for the Samaritans due to restrictions imposed by the Ottoman authorities. The manuscript gives witness to this difficult situation since the prayer on the morning of Passover is reported to be held in the city of Nablus, and not on Mount Gerizim, according to the title of that part. The page shown on this image gives a list of Biblical passages to be recited during this service.

The manuscript was among those brought from Nablus to London by the Samaritan Jacob ash-Shalaby in 1854, and it became part of the manuscript collection of Mayer Sulzberger in 1912. Sulzberger (1843‒1923), a leading judge and a most important public figure in Philadelphia, and the first president of Dropsie College, was born in Germany and came to the US as a child after the revolution of 1848. His collection of Samaritan manuscripts is one of the biggest and most important world-wide.

A century of Letterheads of the Dropsie College - Annenberg Institute - Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies

Among singular and unique items found in the archives of the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, some documents testify to mundane practices that are part of institutional everyday life. An example of such items is the various letterheads of the Katz Center in all its incarnations (from the Dropsie College through the Annenberg Institute). While one may think of letterheads as mere "frames" of the actual

One can begin by reflecting on the transformations in the title of the letterheads: the letterhead of "The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning Philadelphia" demonstrates that the key factor in determining this institute's scope related to language. It may indicate a specific concern with textual material, making one wonder if Yiddish, Ladino and Judeo-Arabic cultures would have been conceived as 'cognate.' When Dropsie University transformed into the "Annenberg Research Institute for Judaic and Near Eastern Studies,", one notices a shift from language to a more general idea of Judaism which appears in conjunction with a clear geographic indicator; while the literature and history of American Jewry seems to fall under the category of 'Judaic,' it seems beyond the key concept of an institute that examined also the 'Near East.' Once the Institute was encompassed as part of the University of Pennsylvania, the general form of "Judaic Studies" remained, leaving more room for interpretation. Under the leadership of David Ruderman another transformation of the Center is apparent in the letterhead

Interestingly, individual names on the letterheads play an important role only in the Annenberg Institute letterhead and do not play a role in the other letterheads. With the integration of the center into the University of Pennsylvania system, this has changed: the growing prominence of the Penn iconography secured the institutional authority of the Center; although the Center was housed in the same building of the Annenberg Institute (both letterheads relate to the same address on Walnut street), the letterheads convey an important shift from being tied to prominent individual figures to a well-established academic institution.

Other changes in fonts and graphic sensibilities add to the idea that letterheads are not just containers of messages; rather they deliver other messages that are very clear to those who compose them and are clear in much more subtle ways to those who use them (or read them) in their scholarly everyday life.

A century of Letterheads of the Dropsie College - Annenberg Institute - Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies

Among singular and unique items found in the archives of the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, some documents testify to mundane practices that are part of institutional everyday life. An example of such items is the various letterheads of the Katz Center in all its incarnations (from the Dropsie College through the Annenberg Institute). While one may think of letterheads as mere "frames" of the actual

One can begin by reflecting on the transformations in the title of the letterheads: the letterhead of "The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning Philadelphia" demonstrates that the key factor in determining this institute's scope related to language. It may indicate a specific concern with textual material, making one wonder if Yiddish, Ladino and Judeo-Arabic cultures would have been conceived as 'cognate.' When Dropsie University transformed into the "Annenberg Research Institute for Judaic and Near Eastern Studies,", one notices a shift from language to a more general idea of Judaism which appears in conjunction with a clear geographic indicator; while the literature and history of American Jewry seems to fall under the category of 'Judaic,' it seems beyond the key concept of an institute that examined also the 'Near East.' Once the Institute was encompassed as part of the University of Pennsylvania, the general form of "Judaic Studies" remained, leaving more room for interpretation. Under the leadership of David Ruderman another transformation of the Center is apparent in the letterhead

Interestingly, individual names on the letterheads play an important role only in the Annenberg Institute letterhead and do not play a role in the other letterheads. With the integration of the center into the University of Pennsylvania system, this has changed: the growing prominence of the Penn iconography secured the institutional authority of the Center; although the Center was housed in the same building of the Annenberg Institute (both letterheads relate to the same address on Walnut street), the letterheads convey an important shift from being tied to prominent individual figures to a well-established academic institution.

Other changes in fonts and graphic sensibilities add to the idea that letterheads are not just containers of messages; rather they deliver other messages that are very clear to those who compose them and are clear in much more subtle ways to those who use them (or read them) in their scholarly everyday life.

A century of Letterheads of the Dropsie College - Annenberg Institute - Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies

Among singular and unique items found in the archives of the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, some documents testify to mundane practices that are part of institutional everyday life. An example of such items is the various letterheads of the Katz Center in all its incarnations (from the Dropsie College through the Annenberg Institute). While one may think of letterheads as mere "frames" of the actual

One can begin by reflecting on the transformations in the title of the letterheads: the letterhead of "The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning Philadelphia" demonstrates that the key factor in determining this institute's scope related to language. It may indicate a specific concern with textual material, making one wonder if Yiddish, Ladino and Judeo-Arabic cultures would have been conceived as 'cognate.' When Dropsie University transformed into the "Annenberg Research Institute for Judaic and Near Eastern Studies,", one notices a shift from language to a more general idea of Judaism which appears in conjunction with a clear geographic indicator; while the literature and history of American Jewry seems to fall under the category of 'Judaic,' it seems beyond the key concept of an institute that examined also the 'Near East.' Once the Institute was encompassed as part of the University of Pennsylvania, the general form of "Judaic Studies" remained, leaving more room for interpretation. Under the leadership of David Ruderman another transformation of the Center is apparent in the letterhead

Interestingly, individual names on the letterheads play an important role only in the Annenberg Institute letterhead and do not play a role in the other letterheads. With the integration of the center into the University of Pennsylvania system, this has changed: the growing prominence of the Penn iconography secured the institutional authority of the Center; although the Center was housed in the same building of the Annenberg Institute (both letterheads relate to the same address on Walnut street), the letterheads convey an important shift from being tied to prominent individual figures to a well-established academic institution.

Other changes in fonts and graphic sensibilities add to the idea that letterheads are not just containers of messages; rather they deliver other messages that are very clear to those who compose them and are clear in much more subtle ways to those who use them (or read them) in their scholarly everyday life.

A century of Letterheads of the Dropsie College - Annenberg Institute - Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies

Among singular and unique items found in the archives of the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, some documents testify to mundane practices that are part of institutional everyday life. An example of such items is the various letterheads of the Katz Center in all its incarnations (from the Dropsie College through the Annenberg Institute). While one may think of letterheads as mere "frames" of the actual

One can begin by reflecting on the transformations in the title of the letterheads: the letterhead of "The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning Philadelphia" demonstrates that the key factor in determining this institute's scope related to language. It may indicate a specific concern with textual material, making one wonder if Yiddish, Ladino and Judeo-Arabic cultures would have been conceived as 'cognate.' When Dropsie University transformed into the "Annenberg Research Institute for Judaic and Near Eastern Studies,", one notices a shift from language to a more general idea of Judaism which appears in conjunction with a clear geographic indicator; while the literature and history of American Jewry seems to fall under the category of 'Judaic,' it seems beyond the key concept of an institute that examined also the 'Near East.' Once the Institute was encompassed as part of the University of Pennsylvania, the general form of "Judaic Studies" remained, leaving more room for interpretation. Under the leadership of David Ruderman another transformation of the Center is apparent in the letterhead

Interestingly, individual names on the letterheads play an important role only in the Annenberg Institute letterhead and do not play a role in the other letterheads. With the integration of the center into the University of Pennsylvania system, this has changed: the growing prominence of the Penn iconography secured the institutional authority of the Center; although the Center was housed in the same building of the Annenberg Institute (both letterheads relate to the same address on Walnut street), the letterheads convey an important shift from being tied to prominent individual figures to a well-established academic institution.

Other changes in fonts and graphic sensibilities add to the idea that letterheads are not just containers of messages; rather they deliver other messages that are very clear to those who compose them and are clear in much more subtle ways to those who use them (or read them) in their scholarly everyday life.

A century of Letterheads of the Dropsie College - Annenberg Institute - Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies

Among singular and unique items found in the archives of the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, some documents testify to mundane practices that are part of institutional everyday life. An example of such items is the various letterheads of the Katz Center in all its incarnations (from the Dropsie College through the Annenberg Institute). While one may think of letterheads as mere "frames" of the actual

One can begin by reflecting on the transformations in the title of the letterheads: the letterhead of "The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning Philadelphia" demonstrates that the key factor in determining this institute's scope related to language. It may indicate a specific concern with textual material, making one wonder if Yiddish, Ladino and Judeo-Arabic cultures would have been conceived as 'cognate.' When Dropsie University transformed into the "Annenberg Research Institute for Judaic and Near Eastern Studies,", one notices a shift from language to a more general idea of Judaism which appears in conjunction with a clear geographic indicator; while the literature and history of American Jewry seems to fall under the category of 'Judaic,' it seems beyond the key concept of an institute that examined also the 'Near East.' Once the Institute was encompassed as part of the University of Pennsylvania, the general form of "Judaic Studies" remained, leaving more room for interpretation. Under the leadership of David Ruderman another transformation of the Center is apparent in the letterhead

Interestingly, individual names on the letterheads play an important role only in the Annenberg Institute letterhead and do not play a role in the other letterheads. With the integration of the center into the University of Pennsylvania system, this has changed: the growing prominence of the Penn iconography secured the institutional authority of the Center; although the Center was housed in the same building of the Annenberg Institute (both letterheads relate to the same address on Walnut street), the letterheads convey an important shift from being tied to prominent individual figures to a well-established academic institution.

Other changes in fonts and graphic sensibilities add to the idea that letterheads are not just containers of messages; rather they deliver other messages that are very clear to those who compose them and are clear in much more subtle ways to those who use them (or read them) in their scholarly everyday life.

A century of Letterheads of the Dropsie College - Annenberg Institute - Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies

Among singular and unique items found in the archives of the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, some documents testify to mundane practices that are part of institutional everyday life. An example of such items is the various letterheads of the Katz Center in all its incarnations (from the Dropsie College through the Annenberg Institute). While one may think of letterheads as mere "frames" of the actual

One can begin by reflecting on the transformations in the title of the letterheads: the letterhead of "The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning Philadelphia" demonstrates that the key factor in determining this institute's scope related to language. It may indicate a specific concern with textual material, making one wonder if Yiddish, Ladino and Judeo-Arabic cultures would have been conceived as 'cognate.' When Dropsie University transformed into the "Annenberg Research Institute for Judaic and Near Eastern Studies,", one notices a shift from language to a more general idea of Judaism which appears in conjunction with a clear geographic indicator; while the literature and history of American Jewry seems to fall under the category of 'Judaic,' it seems beyond the key concept of an institute that examined also the 'Near East.' Once the Institute was encompassed as part of the University of Pennsylvania, the general form of "Judaic Studies" remained, leaving more room for interpretation. Under the leadership of David Ruderman another transformation of the Center is apparent in the letterhead

Interestingly, individual names on the letterheads play an important role only in the Annenberg Institute letterhead and do not play a role in the other letterheads. With the integration of the center into the University of Pennsylvania system, this has changed: the growing prominence of the Penn iconography secured the institutional authority of the Center; although the Center was housed in the same building of the Annenberg Institute (both letterheads relate to the same address on Walnut street), the letterheads convey an important shift from being tied to prominent individual figures to a well-established academic institution.

Other changes in fonts and graphic sensibilities add to the idea that letterheads are not just containers of messages; rather they deliver other messages that are very clear to those who compose them and are clear in much more subtle ways to those who use them (or read them) in their scholarly everyday life.

A century of Letterheads of the Dropsie College - Annenberg Institute - Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies

Among singular and unique items found in the archives of the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, some documents testify to mundane practices that are part of institutional everyday life. An example of such items is the various letterheads of the Katz Center in all its incarnations (from the Dropsie College through the Annenberg Institute). While one may think of letterheads as mere "frames" of the actual

One can begin by reflecting on the transformations in the title of the letterheads: the letterhead of "The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning Philadelphia" demonstrates that the key factor in determining this institute's scope related to language. It may indicate a specific concern with textual material, making one wonder if Yiddish, Ladino and Judeo-Arabic cultures would have been conceived as 'cognate.' When Dropsie University transformed into the "Annenberg Research Institute for Judaic and Near Eastern Studies,", one notices a shift from language to a more general idea of Judaism which appears in conjunction with a clear geographic indicator; while the literature and history of American Jewry seems to fall under the category of 'Judaic,' it seems beyond the key concept of an institute that examined also the 'Near East.' Once the Institute was encompassed as part of the University of Pennsylvania, the general form of "Judaic Studies" remained, leaving more room for interpretation. Under the leadership of David Ruderman another transformation of the Center is apparent in the letterhead

Interestingly, individual names on the letterheads play an important role only in the Annenberg Institute letterhead and do not play a role in the other letterheads. With the integration of the center into the University of Pennsylvania system, this has changed: the growing prominence of the Penn iconography secured the institutional authority of the Center; although the Center was housed in the same building of the Annenberg Institute (both letterheads relate to the same address on Walnut street), the letterheads convey an important shift from being tied to prominent individual figures to a well-established academic institution.

Other changes in fonts and graphic sensibilities add to the idea that letterheads are not just containers of messages; rather they deliver other messages that are very clear to those who compose them and are clear in much more subtle ways to those who use them (or read them) in their scholarly everyday life.

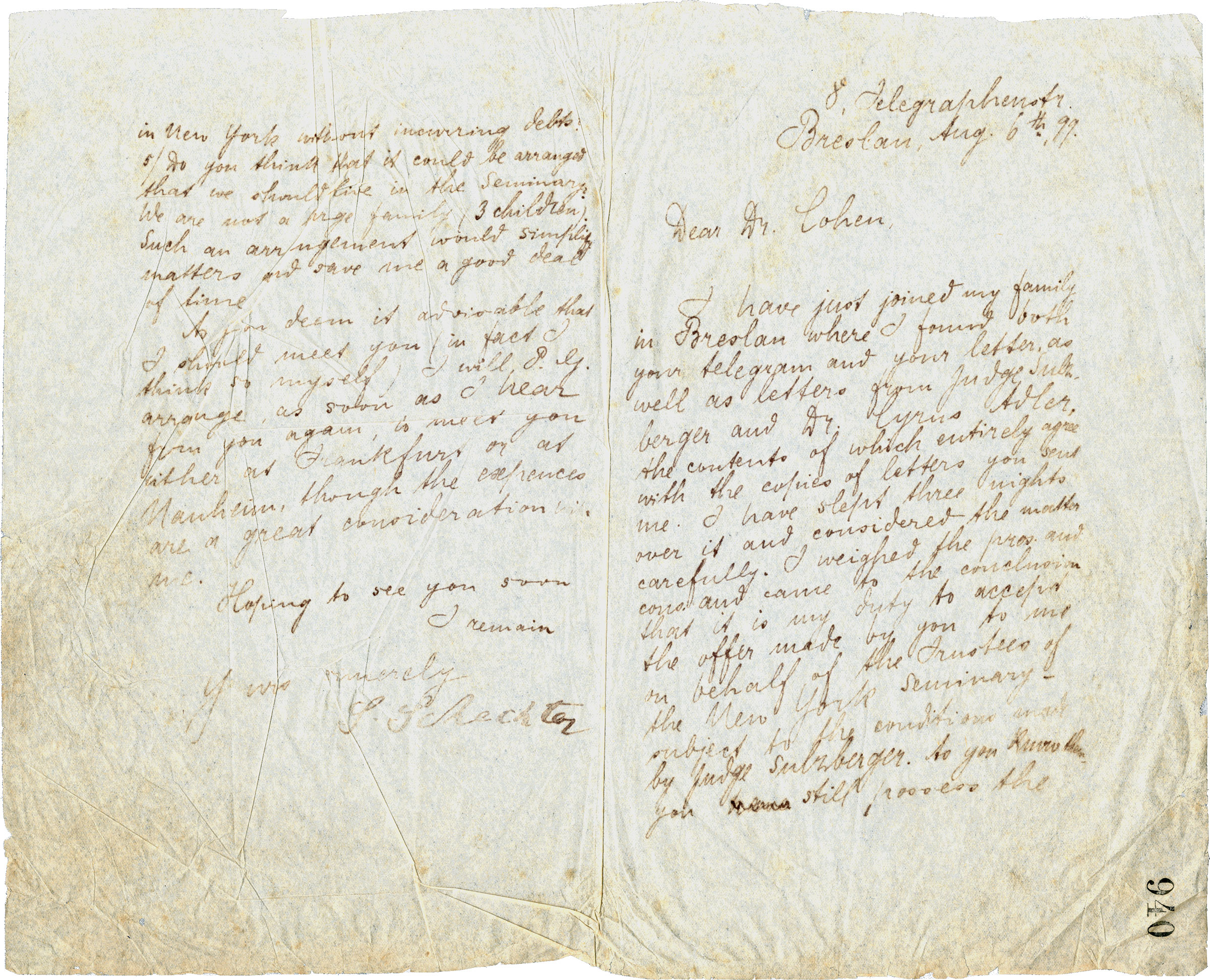

Solomon Schechter accepts the post of director of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTSA) in New York City

In 1902 Solomon Schechter moved from Cambridge/ England to New York City in order to take office as the director of and instructor in Talmud and history at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTSA). The image displayed shows the first page of Schechter's acceptance letter to Max Cohen, member of the Board of Trustees of the JTSA. After the demise in 1873 of Maimonides College, the first modern rabbinical seminary in the United States, the reform-oriented movement of Judaism established the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati in 1875. In 1886, the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), the successor to Maimonides College's more traditional orientation, was founded in New York under the supervision of the Reverend Sabato Morais, who had taught Bible at Maimonides College and was the minister of the Spanish and Portuguese Congregaton Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia. In 1902, five years after Morais' death, the JTS merged with a new legal corporation: the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTSA). During the previous decade, the Seminary's leaders had recruited Schechter to succeed Morais and lead the institution.

In his acceptance letter, Schechter expresses his thoughtful balance of reasons about his decision whether or not to follow the call to New York. As Schechter writes, he finally came to the solution to accept the position offered because he felt it was his "duty." In the same letter, he already started the negotiations with the JTSA board about his post, e.g., he raised the question if he was actually going to be the director of the seminary or rather in charge to change and advancing the outdated curriculum. In fact, with Schechter's move to America the curriculum of the seminary was transformed towards the concepts of the European Wissenschaft des Judentums. Higher requirements to the instructors and students and an emphasis on the academic approach would finally change American Jewish scholarship to a great extent and not least cement the formation of a "Conservative" understanding and practice of Wissenschaft des Judentums in the United States.

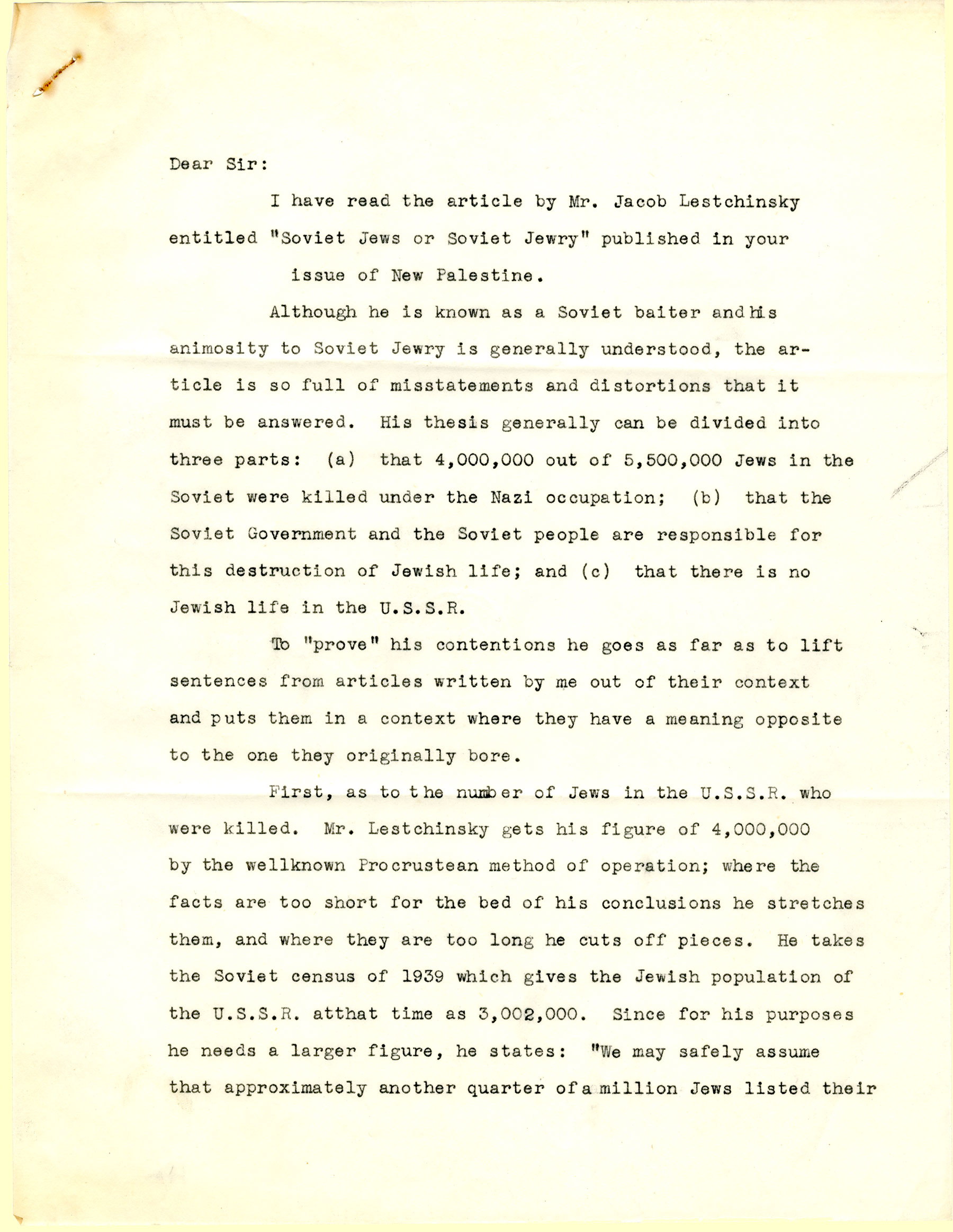

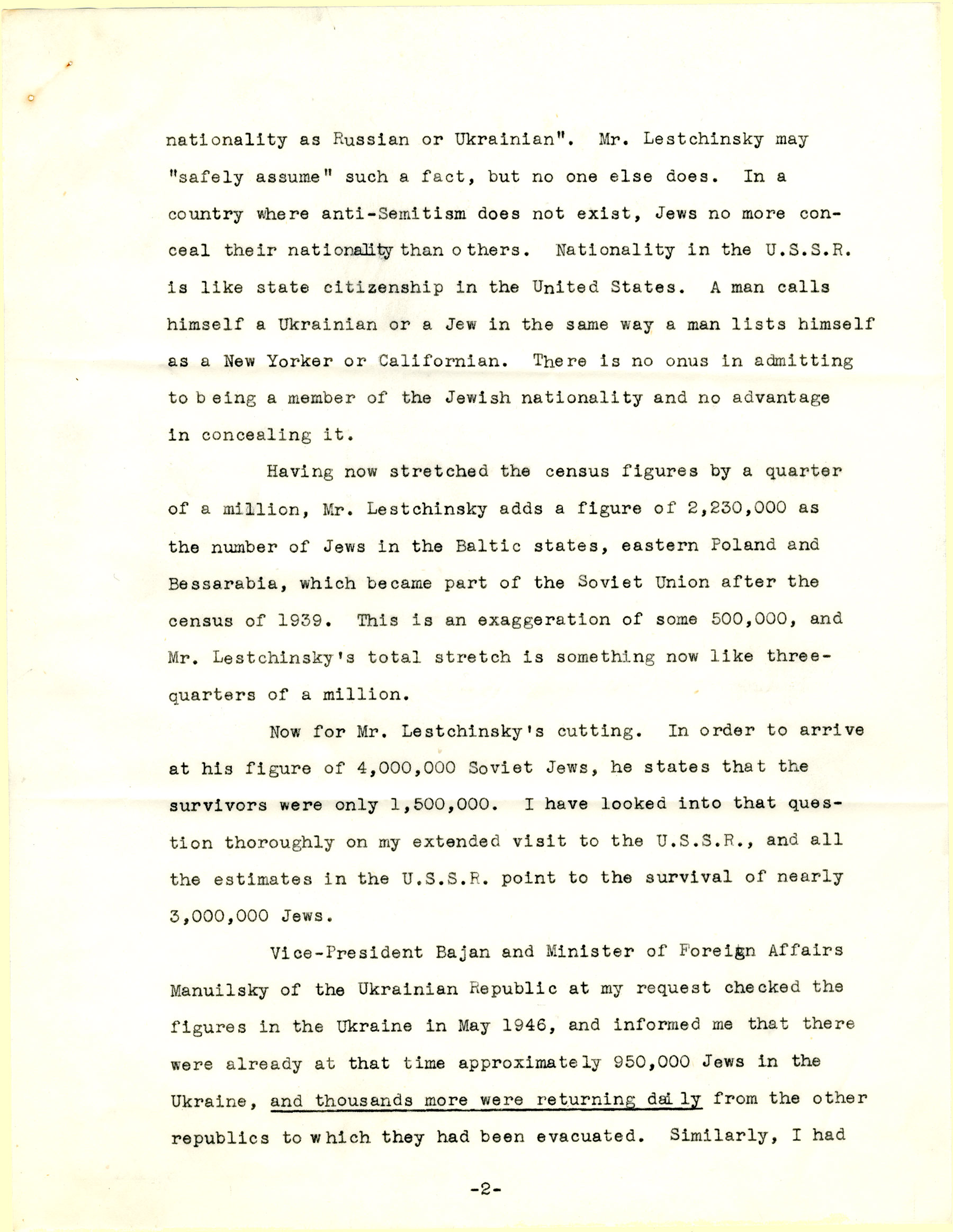

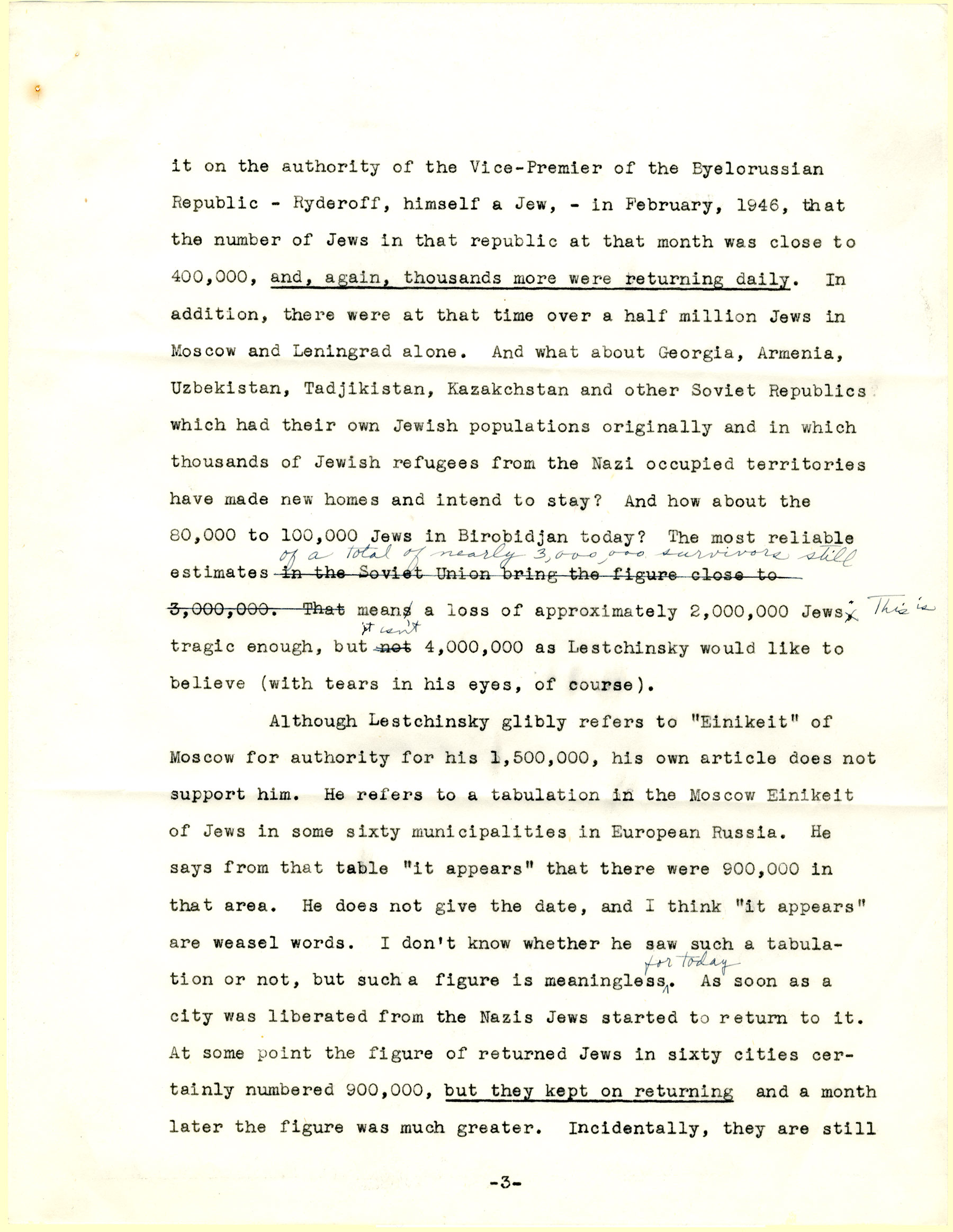

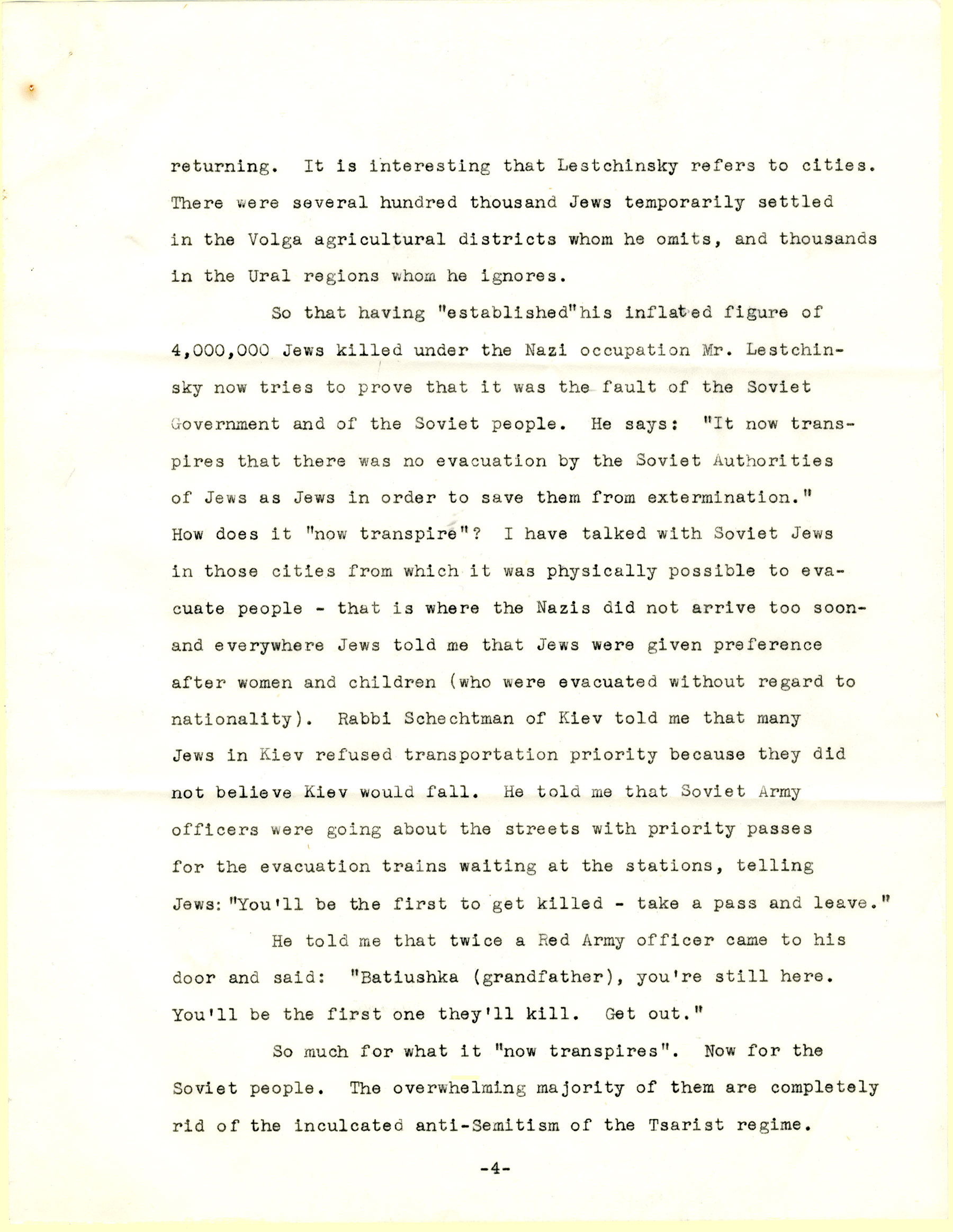

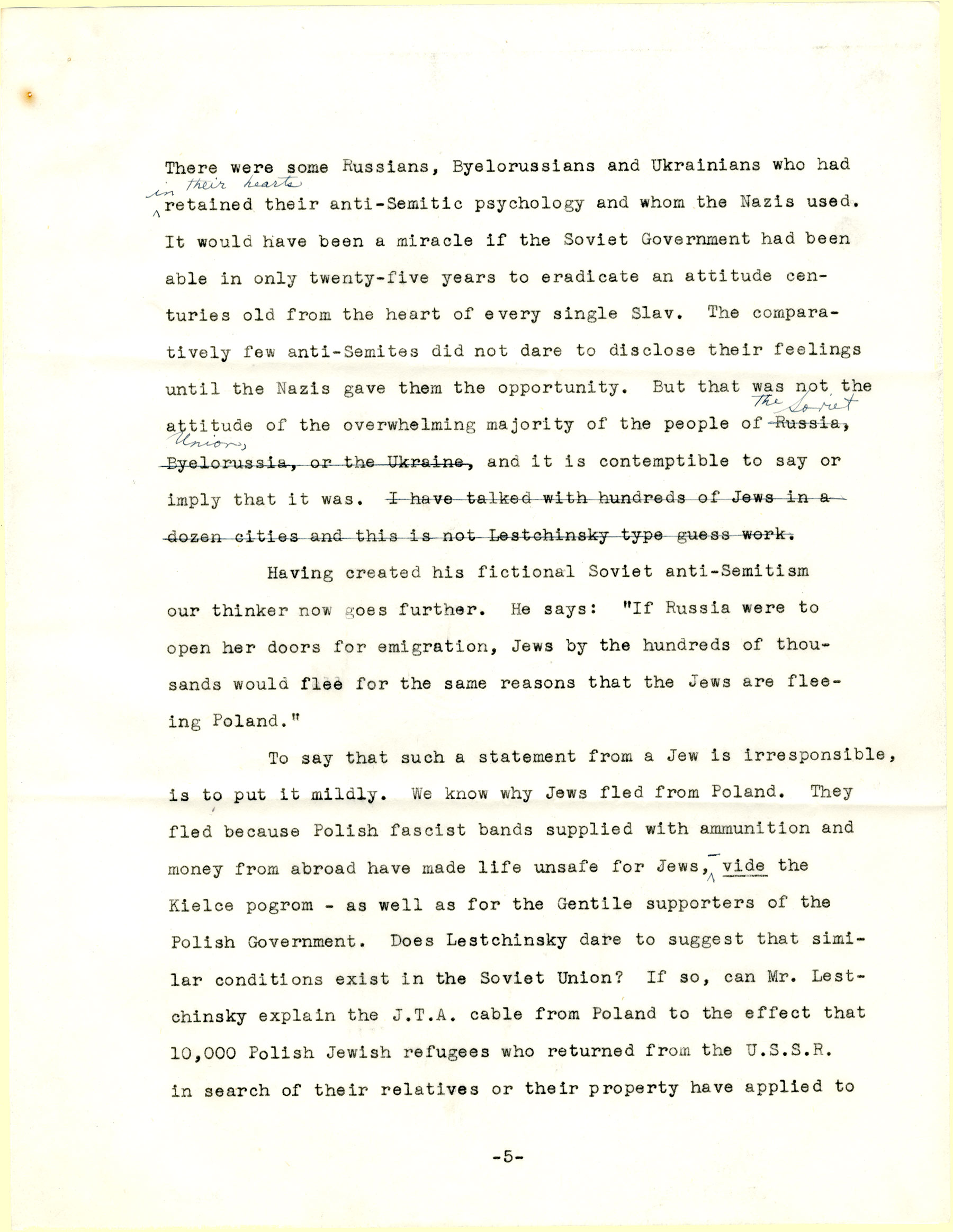

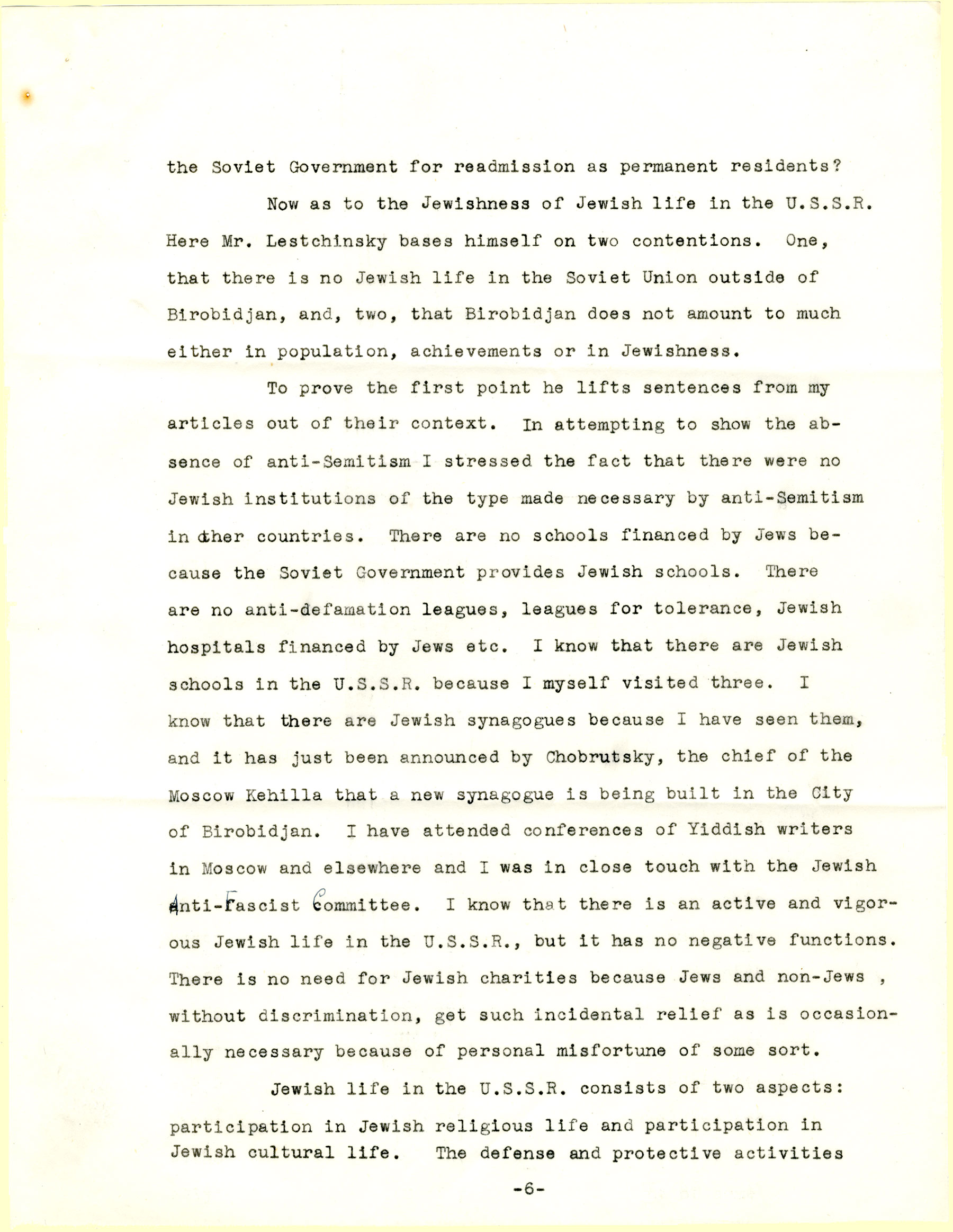

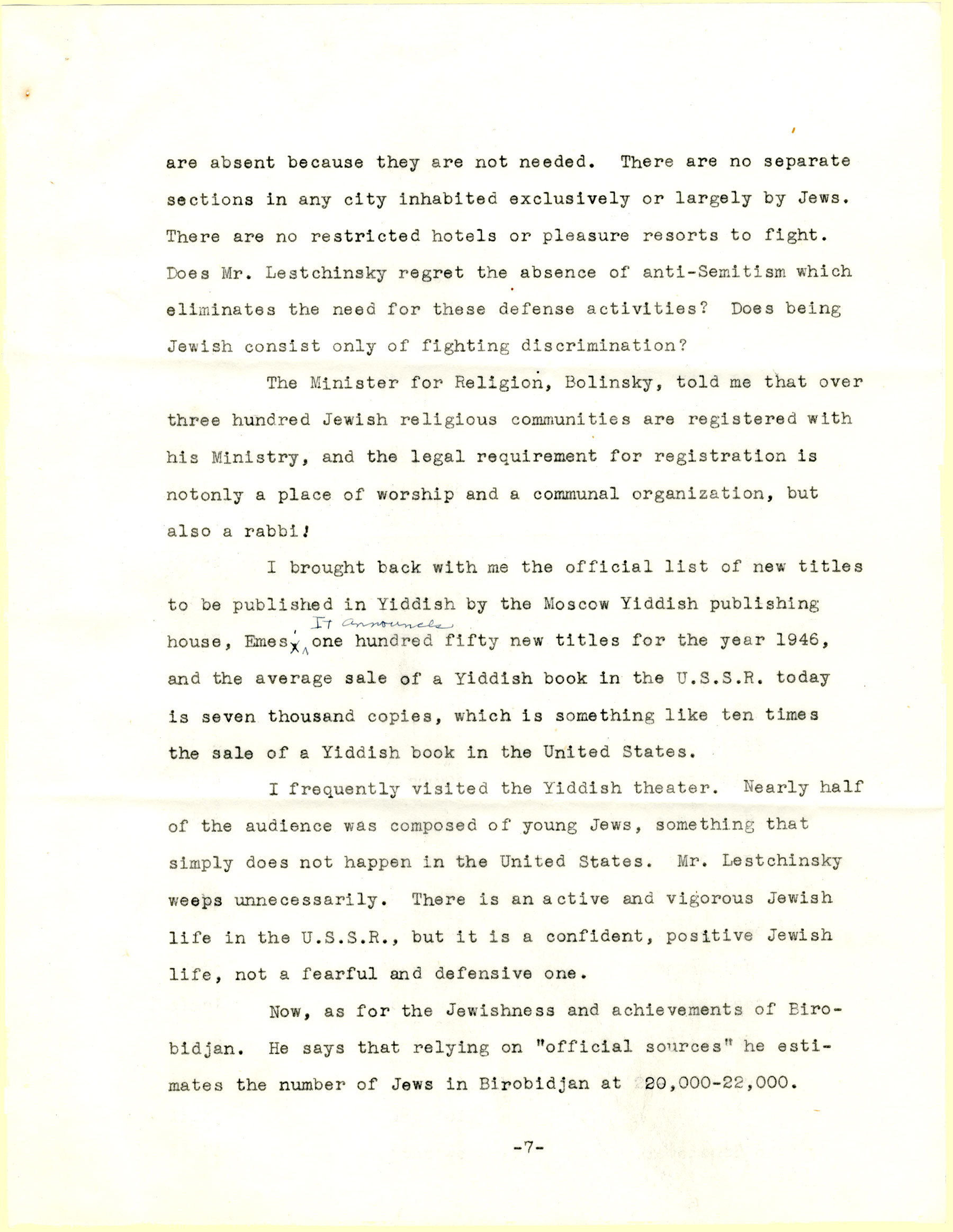

B.Z. Goldberg's letter to The New Palestine

In this 11-page undated draft letter by journalist B.Z. Goldberg to the editor of The New Palestine, we have a glimpse into a broader ideological clash

Goldberg's letter also offers insight into the highly politicized nature of "counting Jews" in both life and death. In dismissing Lestschinsky as a "weeper," Goldberg's rhetoric closely parallels that of Soviet Jewish demographers in the early 1930s who mocked Lestschinsky for allegedly inflating the number of anti-Jewish pogrom casualties during the Russian Civil War. In challenging Lestschinsky's arithmetic, Goldberg contests the pessimism underlying prevailing conceptions of Jewish identity: "Does being Jewish consist only of fighting discrimination?" he queries. His answer: "There is an active and vigorous Jewish life in the USSR, but it is a confident, positive Jewish life, not a fearful and defensive one." Events transpiring between 1948 and 1953

B.Z. Goldberg's letter to The New Palestine

In this 11-page undated draft letter by journalist B.Z. Goldberg to the editor of The New Palestine, we have a glimpse into a broader ideological clash

Goldberg's letter also offers insight into the highly politicized nature of "counting Jews" in both life and death. In dismissing Lestschinsky as a "weeper," Goldberg's rhetoric closely parallels that of Soviet Jewish demographers in the early 1930s who mocked Lestschinsky for allegedly inflating the number of anti-Jewish pogrom casualties during the Russian Civil War. In challenging Lestschinsky's arithmetic, Goldberg contests the pessimism underlying prevailing conceptions of Jewish identity: "Does being Jewish consist only of fighting discrimination?" he queries. His answer: "There is an active and vigorous Jewish life in the USSR, but it is a confident, positive Jewish life, not a fearful and defensive one." Events transpiring between 1948 and 1953

B.Z. Goldberg's letter to The New Palestine

In this 11-page undated draft letter by journalist B.Z. Goldberg to the editor of The New Palestine, we have a glimpse into a broader ideological clash

Goldberg's letter also offers insight into the highly politicized nature of "counting Jews" in both life and death. In dismissing Lestschinsky as a "weeper," Goldberg's rhetoric closely parallels that of Soviet Jewish demographers in the early 1930s who mocked Lestschinsky for allegedly inflating the number of anti-Jewish pogrom casualties during the Russian Civil War. In challenging Lestschinsky's arithmetic, Goldberg contests the pessimism underlying prevailing conceptions of Jewish identity: "Does being Jewish consist only of fighting discrimination?" he queries. His answer: "There is an active and vigorous Jewish life in the USSR, but it is a confident, positive Jewish life, not a fearful and defensive one." Events transpiring between 1948 and 1953

B.Z. Goldberg's letter to The New Palestine

In this 11-page undated draft letter by journalist B.Z. Goldberg to the editor of The New Palestine, we have a glimpse into a broader ideological clash

Goldberg's letter also offers insight into the highly politicized nature of "counting Jews" in both life and death. In dismissing Lestschinsky as a "weeper," Goldberg's rhetoric closely parallels that of Soviet Jewish demographers in the early 1930s who mocked Lestschinsky for allegedly inflating the number of anti-Jewish pogrom casualties during the Russian Civil War. In challenging Lestschinsky's arithmetic, Goldberg contests the pessimism underlying prevailing conceptions of Jewish identity: "Does being Jewish consist only of fighting discrimination?" he queries. His answer: "There is an active and vigorous Jewish life in the USSR, but it is a confident, positive Jewish life, not a fearful and defensive one." Events transpiring between 1948 and 1953

B.Z. Goldberg's letter to The New Palestine

In this 11-page undated draft letter by journalist B.Z. Goldberg to the editor of The New Palestine, we have a glimpse into a broader ideological clash

Goldberg's letter also offers insight into the highly politicized nature of "counting Jews" in both life and death. In dismissing Lestschinsky as a "weeper," Goldberg's rhetoric closely parallels that of Soviet Jewish demographers in the early 1930s who mocked Lestschinsky for allegedly inflating the number of anti-Jewish pogrom casualties during the Russian Civil War. In challenging Lestschinsky's arithmetic, Goldberg contests the pessimism underlying prevailing conceptions of Jewish identity: "Does being Jewish consist only of fighting discrimination?" he queries. His answer: "There is an active and vigorous Jewish life in the USSR, but it is a confident, positive Jewish life, not a fearful and defensive one." Events transpiring between 1948 and 1953

B.Z. Goldberg's letter to The New Palestine

In this 11-page undated draft letter by journalist B.Z. Goldberg to the editor of The New Palestine, we have a glimpse into a broader ideological clash

Goldberg's letter also offers insight into the highly politicized nature of "counting Jews" in both life and death. In dismissing Lestschinsky as a "weeper," Goldberg's rhetoric closely parallels that of Soviet Jewish demographers in the early 1930s who mocked Lestschinsky for allegedly inflating the number of anti-Jewish pogrom casualties during the Russian Civil War. In challenging Lestschinsky's arithmetic, Goldberg contests the pessimism underlying prevailing conceptions of Jewish identity: "Does being Jewish consist only of fighting discrimination?" he queries. His answer: "There is an active and vigorous Jewish life in the USSR, but it is a confident, positive Jewish life, not a fearful and defensive one." Events transpiring between 1948 and 1953

B.Z. Goldberg's letter to The New Palestine

In this 11-page undated draft letter by journalist B.Z. Goldberg to the editor of The New Palestine, we have a glimpse into a broader ideological clash

Goldberg's letter also offers insight into the highly politicized nature of "counting Jews" in both life and death. In dismissing Lestschinsky as a "weeper," Goldberg's rhetoric closely parallels that of Soviet Jewish demographers in the early 1930s who mocked Lestschinsky for allegedly inflating the number of anti-Jewish pogrom casualties during the Russian Civil War. In challenging Lestschinsky's arithmetic, Goldberg contests the pessimism underlying prevailing conceptions of Jewish identity: "Does being Jewish consist only of fighting discrimination?" he queries. His answer: "There is an active and vigorous Jewish life in the USSR, but it is a confident, positive Jewish life, not a fearful and defensive one." Events transpiring between 1948 and 1953

B.Z. Goldberg's letter to The New Palestine

In this 11-page undated draft letter by journalist B.Z. Goldberg to the editor of The New Palestine, we have a glimpse into a broader ideological clash