Diversity in the Stacks aims to build library collections that represent and reflect the University’s diverse population.

Since the early 1800s, Penn Libraries has collected materials from across South Asia. To date, this collection includes materials in more than 20 of the 74 languages spoken in Pakistan.

The strength of this collection is both in its eclecticism and expansiveness, with more than 19,000 items in Urdu alone. There’s a strong emphasis on poetry and other literary collections, religious texts, musical recordings, reference materials, and scholarly works on these languages. This post highlights the regional, ethnic, and linguistic diversity of Pakistan through a limited selection of the extraordinary breadth of materials at Penn.

Perhaps the largest category of Pakistani vernacular materials in the Libraries’ collection is poetry and literary prose works. A small sample of Sindhi works available in translation includes a collection of four prominent poets, a deep dive into the poet-saint Shah Abdul Latif with Sindhi Naksh script on facing pages, and contemporary contributions to a translated collection of Sindhi and Urdu pieces on Karachi.

(Here are links to both quick and in-depth overviews of Sindh’s literary history if you want to learn more!)

This study of Siraiki poetic style makes a good accompaniment to Khwaja Farid’s poetry. Have a glance at the unique Khowar translation of Muhammad Iqbal, which renders nationalist verse into this sub-regional language. Another highlight is a little-studied assortment of thirteen Brahui poetry collections.

There are several proverb and folktale collections in various Pakistani languages that are worth checking out, accompanied by English or Urdu translations: Shina proverbs (Urdu), Burushaski proverbs, Shina folktales, Torwali folktales, and several Kalam Kohistani folktales (all English).

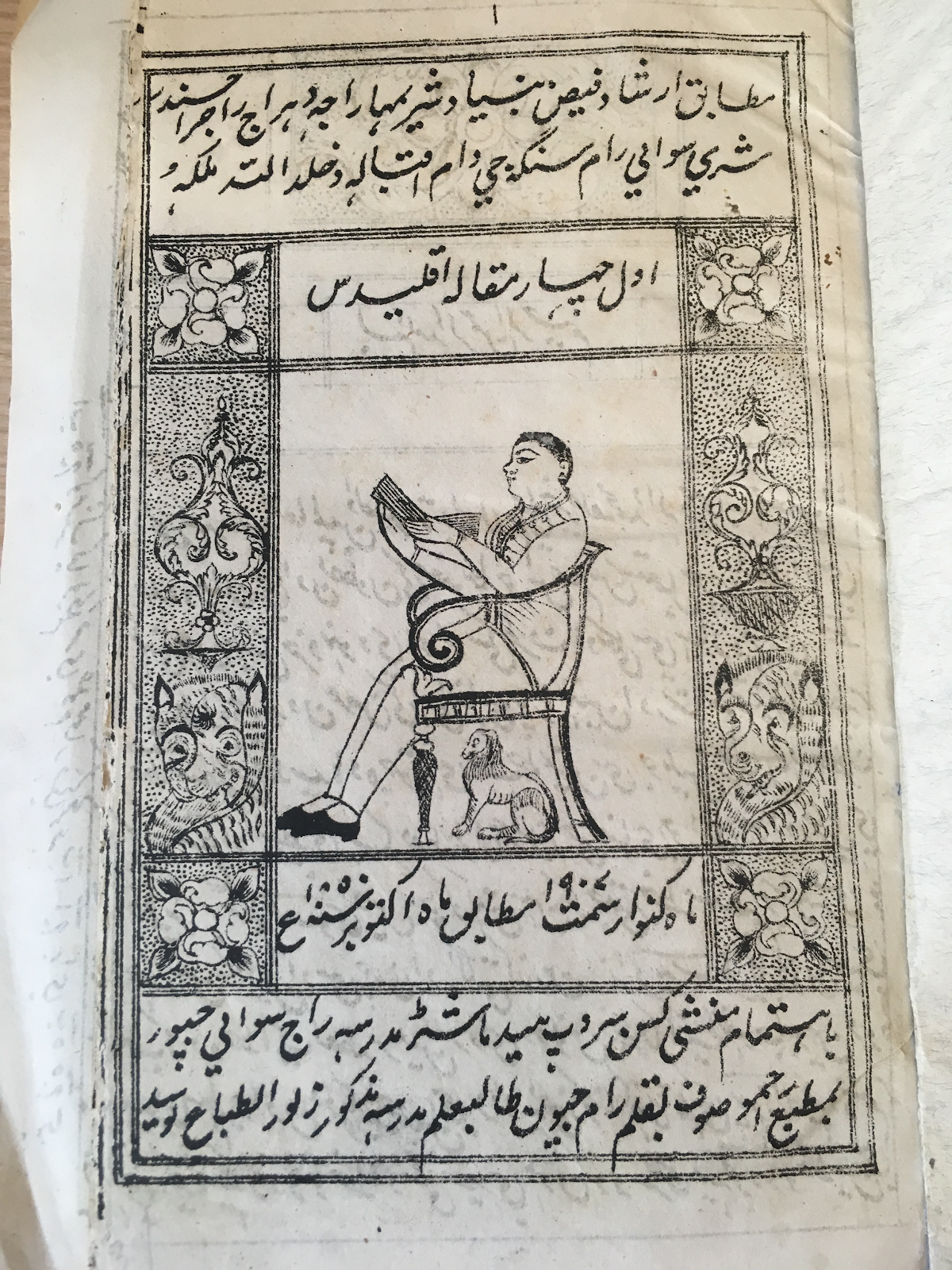

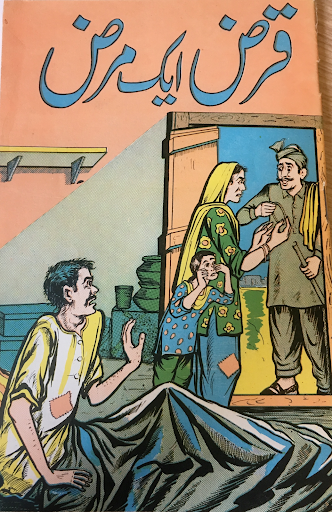

The Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts holds the Pushtu Chapbook collection, emblematic of items found in so many of these languages at Pakistani bazaars. (A few new Urdu chapbooks from Karachi have recently been added, with examples here and here). There are hundreds of works across these vernacular languages, including in Gujari —a language for which we currently have no translated work.

Music is another significant component of the collection, with a range of sound recordings (around 400 across 10+ languages) and textual materials about Pakistani musical traditions. Holdings range far beyond better-known Pakistani artists such as Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Nur Jehan. Consider listening to Allah Bakhsh Tampi’s Tarang or Abdullah Ado’s ‘Disco’, in Baluchi. Check out Ghulam Nabi Brahui’s Mahfil, and get a visual sense of a live mahfil by Ustad Noor Hayat, a contemporary Brahui musician. We have Fozia Soomro recordings in both Sindhi and Marwari. This album by Reshma is a good example of Punjabi folk music. And for Siraiki, check out this album by Muhammad Husain Bindiyal.

In Kashmiri, we have a recording of artists of the Rubab, a lute-like stringed instrument. Ahmad Gul celebrates, in Pushtu, the sixteenth-century Sufi-saint Kaka Sahib. Pathanay Khan — a somewhat lesser known, but still nationally renowned artist — sings in several languages, including this multi-volume set in Hindko and Punjabi and this Siraiki rendition of Bulleh Shah (whose poetry is translated in this book).

The collection also features political recordings, including items from the Pakistan People’s Party (the Bhutto family); a Sindhi album celebrating Makhdum Muhammad Zaman Talibul Moula that typifies the blending of politics, poetry, and Sufi devotionalism in rural Pakistan; and a yet-to-be-catalogued cassette of Afghan nationalist songs.

Religious materials include a Khowar translation of Arabic qasidah devotional poems; translations of the Qur’an in Siraiki, Balti, and Burushaski; Ismaili devotional literature in Burushaski; a collection of Arabic, Persian, and Urdu textbooks from a madrasah syllabus; and tafsir collections in Sindhi, Siraiki, and Kashmiri, including a unique Ahmadi collection – a sect marginalized in Pakistan.

Christopher Shackle’s English-language work on Khoja devotional literature translates and contextualizes Ismaili religious practices through the Khoja community’s dialect of Punjabi and liturgical Khojki script (see Khojki in a “Trader’s List” manuscript from Special Collections). A number of religious traditions other than Islam — for example, Bible translations in Pushtu and this Sindhi account of pilgrimage to the Hindu deity Hinglaj Mata — are also represented.

Other recent additions to the Libraries’ Pakistani vernacular language collection include resources for Pakistani Sign Language (PSL). The organization behind these publications has helped document local sign language variants from across the country and opened several schools, training centers, and support facilities for the Deaf community and their families. 5000 Signs: Pakistan Sign Language Lexicon provides a DVD dictionary of signs and six Pakistani languages developed collaboratively with educators and leaders in the Deaf community . Pakistan Sign Language: 1000 Basic signs is the accompanying book with signs’ images and written word equivalents in these languages. (You can browse the ever-growing lexicon, now available on the PSL app for Android and iOS.)

There are also myriad dictionaries, instructional materials, linguistic studies, and ethnographies that speak to Pakistan’s diverse linguistic and ethnic communities, from a modern documentary ethnologue of Wakhi communities to colonial ethnography on Burushaski speakers and contemporary ethnography on Kohistani communities. From this scholarly bibliography on Dardic languages, to a Siraiki reference grammar and Khowar-English dictionary, the Libraries hosts a plethora of secondary-source materials in English that offer entry points for language study. For readers of these languages, the collection features volumes of vernacular reference works, including in Siraiki and Pushtu.

The strength and uniqueness of the Libraries’ collection of Pakistani vernacular language materials lies in the institution’s depth of expertise for collecting and cataloguing. Of course, challenges persist in developing the collection. Many languages of small communities are exclusively oral, and travel to Pakistan and the ability to collect materials in remote areas remains complex.

Regardless, there is renewed interest in building upon strong existing foundations of Pakistani materials: two direct relationships with local printer/distributors having been established in the last two years in an effort to source more material, with particular focus on smaller regional publishers.

To browse other materials in the Libraries’ Pakistani vernacular language collections, search the Franklin Catalog by language, by keyword, or by call number (PK1900-2895 or PK6700-8000 for most literary works).

YouTube Links to Music and Artists in the Collection:

- Allah Baksh Tampi (on YouTube)

- Abdullah Ado (on YouTube)

- Fozia Soomro (on YouTube)

- Reshma (on YouTube)

- Muhammad Husain Bindiyal (on YouTube)

- Rubab (on YouTube)

- Ghulam Nabi (on YouTube)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Since the early 1800s, Penn Libraries has collected materials from across South Asia. To date, this collection includes materials in more than 20 of the 74 languages spoken in Pakistan. The strength of this collection is both in its eclecticism and expansiveness, with more than 19,000 items in Urdu alone