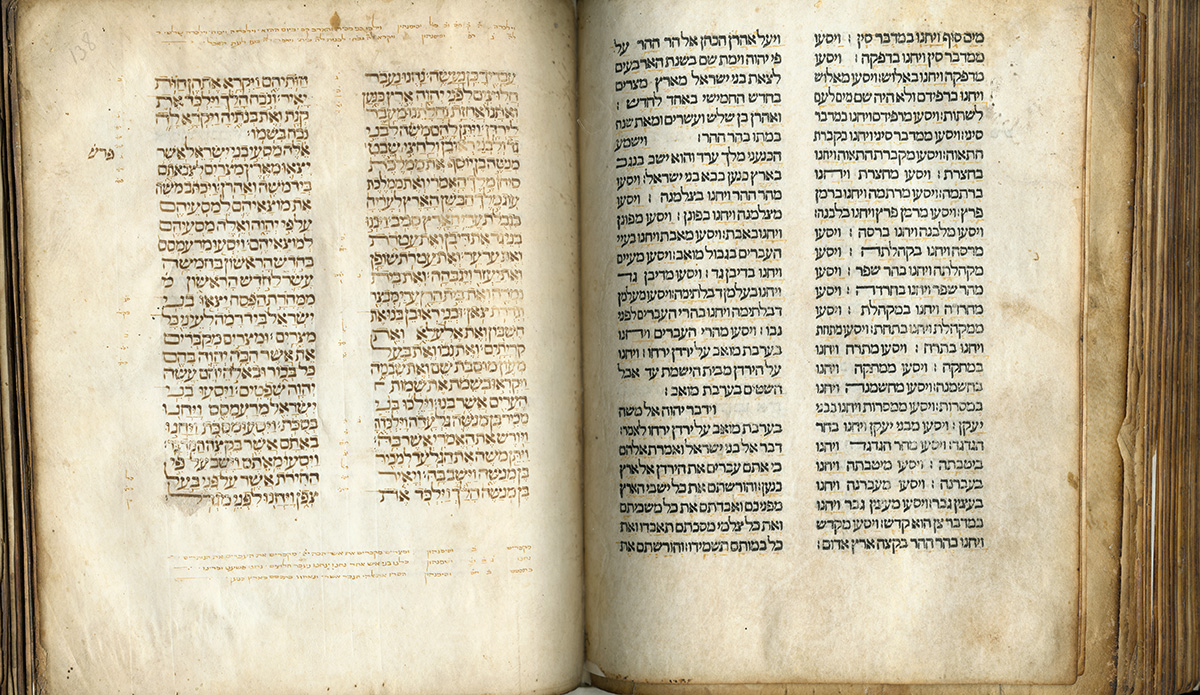

Five out of ten Hebrew incunabula from the Aragonese print shop at Hijar are editions of the Bible printed between 1486 and 1490. They barely provide us with the names of the printer Eliezer Alantansi, its financier, and the proof-reader, all Jews. We search in vain in the colophons for any reference to the wandering printer and type-cutter Alfonso Fernandez de Cordoba, a Castilian silversmith, whose early known footsteps place him in 1476 Valencia, despite the fact that according to some clues he would have been instrumental in the development of the Hijar print shop.

Fernandez de Cordoba's case may not have been exceptional. As is true for the Hebrew humanist printer Juan de Lucena, we must rely on external documentary sources for indirect hints of Fernandez de Cordoba's association with Jews involved in printing activities. However, in sharp contrast with Lucena, we still lack conclusive evidence concerning the fact that Fernandez de Cordoba was a converso. Both may well exemplify the cultural and social predicament of a generation of conversos in a transitional period after the establishment, after 1480, of inquisitional courts that attempted to set clear-cut religious boundaries and taxonomies through the control of the social body and individual consciousness.

Documentary sources frequently associate conversos (though not exclusively) with Bible reading in the vernacular, in connection with new forms of religious devotion, and, thus, from an early date we find several initiatives for the printing of vernacular Bibles by conversos. In 1476, Fernandez de Cordoba associated with a German craftsman for the production of the Biblia Valenciana, a not exceptional case. Two years later, three Aragonese merchants and a notary, all conversos that assiduously socialized with their Jewish relatives, contracted with Pablo Hurus in Saragossa for the printing of another Bible in the vernacular. Inquisitorial persecution hampered these initiatives and the copies were promptly destroyed.

Some developments in the early summer of 1483 in Valencia may be taken into consideration for understanding the background for the establishment, two years later, of a Hebrew print shop at Hijar. For several weeks, the editors in charge of the Biblia Valenciana, among them Daniel Vives, the converso proofreader, had been interrogated by the inquisitors. Key for the latter was to determine if the proofreader or someone else had checked the vernacular translation with a Hebrew original, or if he knew of any Christian holding a Hebrew Bible. Fernandez de Cordoba had been absent from the city in the previous months, and therefore was not included among those under arrest. However, another source specifies that local authorities were looking after him, and in fact he was surreptitiously in Valencia signing, together with a notary and the Jewish financier Zalmati, the terms for the publication of the works of Bishop Jaime Perez de Valencia. Interestingly enough, the latter's work was clearly anti-Jewish. Whether this printing was done under duress or not is uncertain, though, in any event, the publication may have contributed to mollifying some ecclesiastical attitudes toward the editors.

In addition to securing the financial resources for such a venture, Zalmati appears later on as the financier of the Hijar Hebrew print shop. Collaboration between Fernandez de Cordoba and him was not exceptional, and, thus, in 1484 both appear in charge of the printing of another ecclesiastical work, the Breviarium Carthaginense (which, for the first time, contains the seal that will be associated later on with the Hijar Hebrew incunables).

About the same time, the printer Eliezer Alantansi, scion of a prominent family of Huesca and trained professionally as a physician, had been sent by his relatives to the small town of Hijar in order to prevent his youthful intention of converting to Christianity, according to a testimony brought before the inquisitors some years later. Whether or not we grant any reliability to this information, it is not out of the question that Alantansi's transfer to Hijar may have contributed to strengthening his Jewish religious convictions.

In contrast with the Christian type-cutter mentioned in the Guadalajara 1476 Hebrew incunable colophon, Alfonso Fernandez de Cordoba as well as Juan de Lucena were invisible printers. Following the advent of the Inquisition, the participation of conversos in Hebrew print shops became a problematic issue not lacking risks, due to the heretical nature attached to Hebrew culture. Thus, transition to print coincided with a change in the attitudes towards conversos that forced them to find new ways to ease their participation in cultural and social common spaces shared by Jews and Christians, among them, printing and reading. Under these new circumstances, invisibility became an advantage.