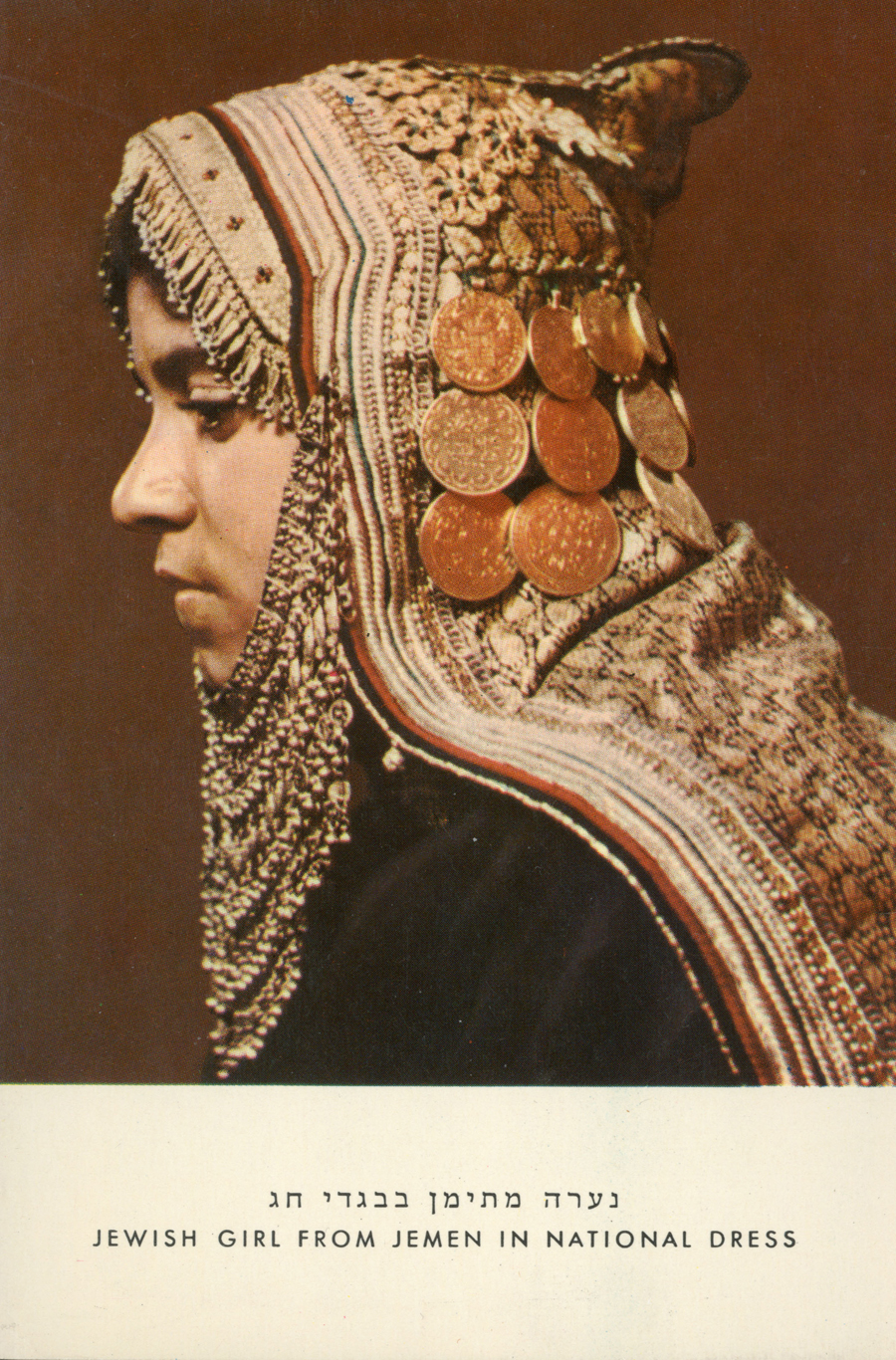

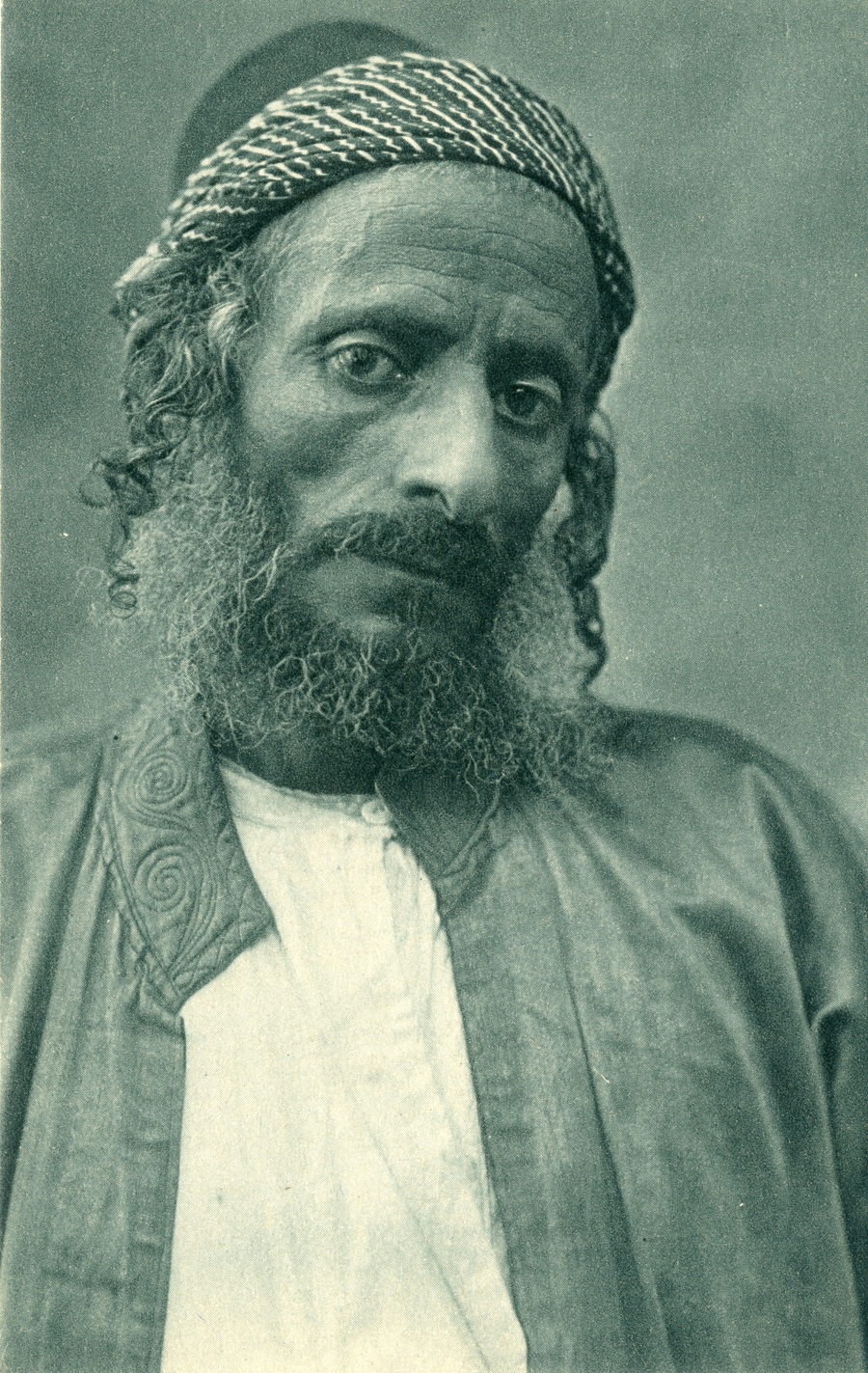

These four portraits of Yemenite Jews in Mandate Palestine come from a collection of approximately 1,250 Holy Land postcards at the library at the Katz Center. The collection was begun during the 1930s by Gualtiero Cividalli, a Florentine Jewish businessman who took his family to Palestine following the rise of fascism in Italy. His daughter Paola continued to build the collection along with many other images and texts related to the Holy Land. Paola and her husband Bertrand Lazard donated these postcards, as well as hundreds of books and maps about the Holy Land, to the Penn Libraries in 2010.

The Paola and Bertrand Lazard Holy Land collection abounds in images of sites holy to Jews, Christians, and Muslims, but there are surprisingly few portrait postcards. The fact that what few portraits appear in the collection are most often of Jews from Yemen reveals what has been called the "gaze" of the observer. This term is often found in post-colonial studies and critiques of Orientalism which analyze the problems and questions arising from the way the non-western world and its inhabitants have been represented, constructed, and re-constructed in the photographs taken of them by western travelers. Instead of focusing on the "gaze" of the "western" observer, however, here we have an opportunity to think about the gaze of those being observed.

Notice that the only figure actually looking at us [the observers], in an amalgamation of sadness and rebuke, is the male. The gazes of the three women represented in these postcards as Yemenite are not turning their eyes to look at us. It is as if they were exotic curiosities staged for display. The absence of their direct look can be understood as a result of their shyness, modesty, and religious or cultural restrictions. It can also be understood instrumentally, assuming that the focus of these photographs is the Yemenite garments or handcrafts and not the women as subjects. This juxtaposition exposes the additional problematic layer of women's representation compared to that of men. Women more than men served, and still do, as objects to observe; it is not just the quantity but also the quality of the representation. Devoting my work to extracting women's voices has made me listen frequently to what seems at first like silence, but then echoes multiple voices. Engaging with these Yemenite women's "non-gazes" can make us, the observers, see them as objects, but it can also force us to look inside ourselves. Indirect-gaze observation results here in an "about face" that may make us feel uncomfortable and can force us into self-reflection. This self-reflection offers a way to "ask" these women to turn their faces and direct their gaze toward the camera so we can look into their eyes and see not just ourselves but also them.