The Wandering Jew is said to have been cursed to live forever, punished for not having let Jesus rest on the wall of his house when he was carrying the cross. The roots of this legend lie buried in the early Middle Ages and start to be visible to us from the 13th century on in the monastic chronicle of St Albans in England, Flores Historiarum composed by Roger de Wendover (d. 1236), followed by the Chronica Majora of Matthew Paris (ca. 1200-1259) at the same monastery. As can be learned from George K. Anderson's monumental The Legend of the Wandering Jew (1965) the tale wandered to the continent and was adapted to almost all languages and cultures of Europe.

A particularly well distributed version of the legend emerged in German in the milieu of the Lutheran Reformation. In this version the Wandering Jew's name was Ahasver and he had been a shoemaker in Jerusalem before the curse. This version in numerous variations became the second most popular German chapbook in the 17th century, surpassed only by the chapbook about Dr. Faust. The chapbooks framed the legend from the time of Jesus with contemporary descriptions of Ahasver's appearance in various European cities and included apocalyptic hints about the approaching return of Jesus to this world. In German his most frequent sobriquet was the Eternal Jew, der ewige Jude.

In the French-speaking regions, songs of the complainte genre about le Juif Errant circulated, emphasizing the tragedy of his fate according to the conventions of the genre. Romantic poetry especially in English and in German embraced the somber, lonely figure as an exemplar of unconventionality. A rich array of visual representations were distributed in conjunction with the narratives and songs, or even separately, varying from anti-Semitic stereotypes to sympathetic and respectful representations. In France the Wandering Jew became the title of a serialized novel (1844-1845) by Eugène Sue (1804-1857) in which the figure himself has a minor but rather scurrilous role as the distributor of cholera.

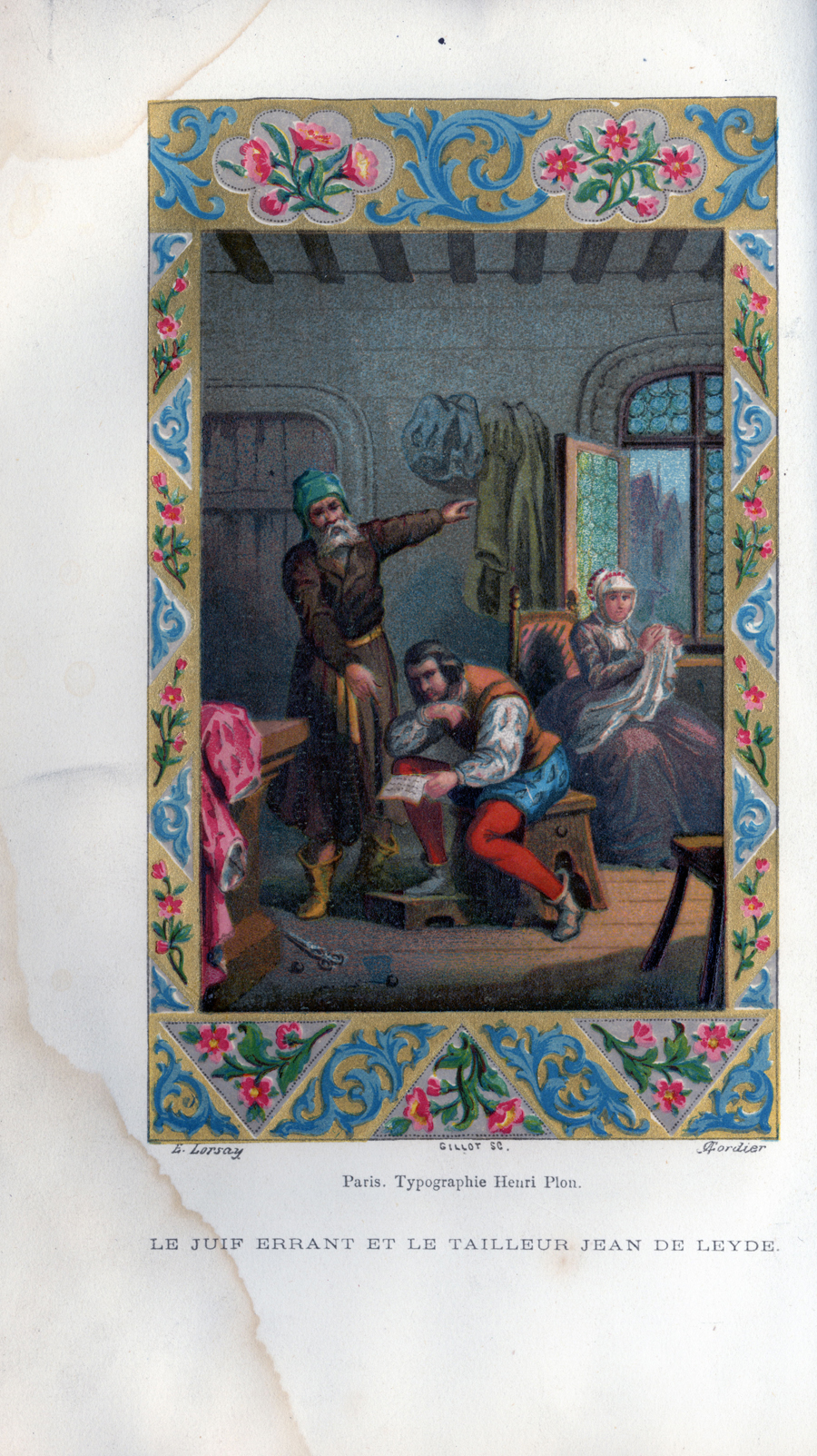

The picture at left is part of a richly illustrated 4th edition of the novel Légendes du juif errant et des seize reines de Munster (Legends of the wandering Jew and the sixteen queens of Munster) by Jacques Albin Simon Collin de Plancy (1794-1881), which includes a mixture of the elements known from German and French traditions. The illustration is signed by the rather famous E. Lorsay, and the book was printed in 1866 at the workshop of the Parisian typographer Henri Plon; this workshop has survived since 1852 until the present day under various ownerships as a publishing house. In the picture the tailor Jean de Leyde, John (Jan) of Leiden, aka John Bockold or John Bockelson, and a leading figure of the short lived Münster Rebellion, reads a letter brought to him by the Wandering Jew Isaac. This name reminds us of the name Isaac Laquedem [here spelled Lakhedem = Isaac from the Orient or Ancient Isaac] that appears in many Wandering Jew traditions from the Netherlands and is confirmed later in the novel in the chapter titled "Le juif errant") summoning him to join the rebels in Münster. Portraying the Wandering Jew as the messenger might have signaled the utopian apocalyptic vision that characterized this Anabaptist enterprise; however, the rebellion was harshly vanquished and Jean-Jan-John cruelly tortured and executed with the other leaders of the Rebellion. The Wandering Jew apparently continued wandering.