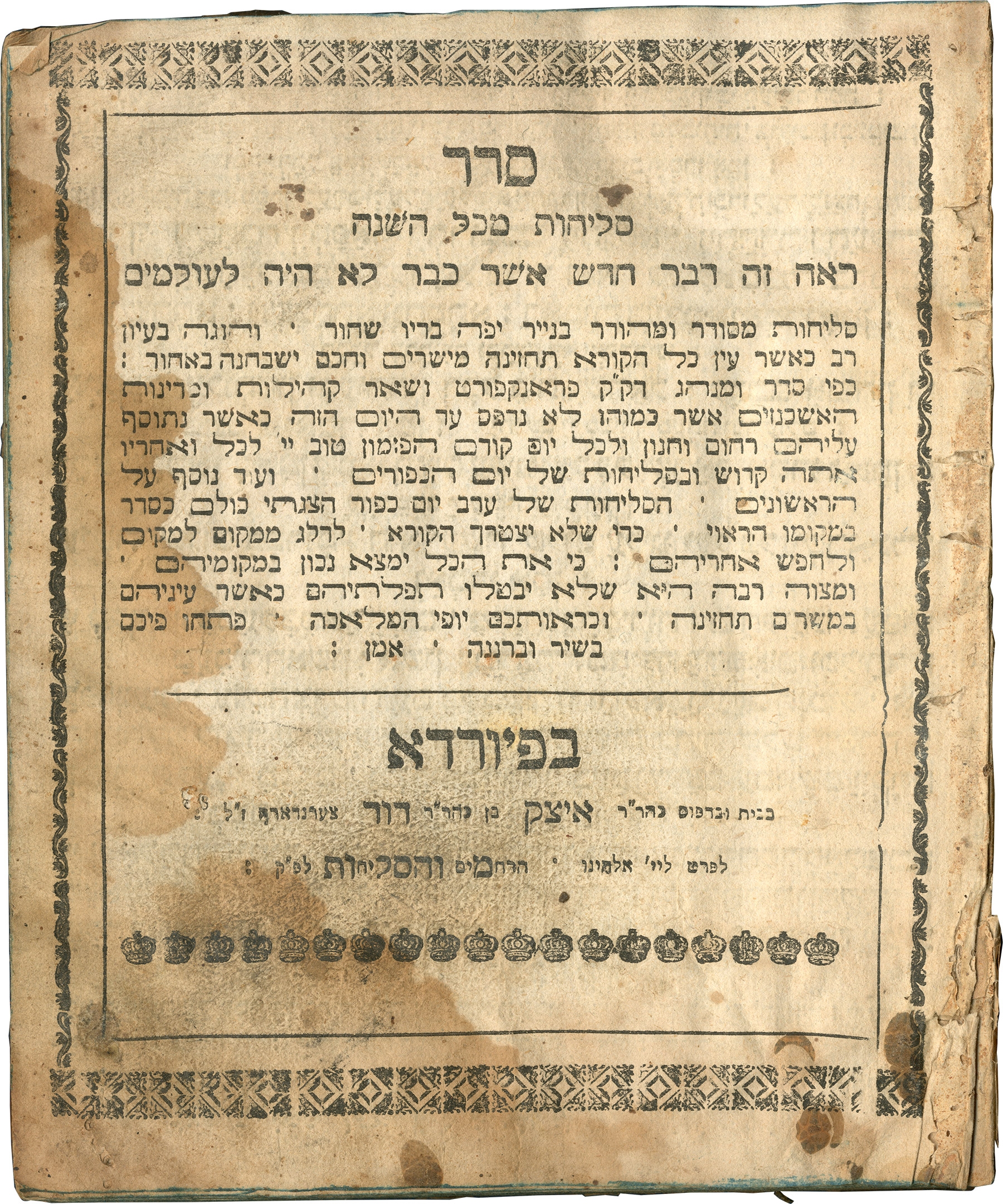

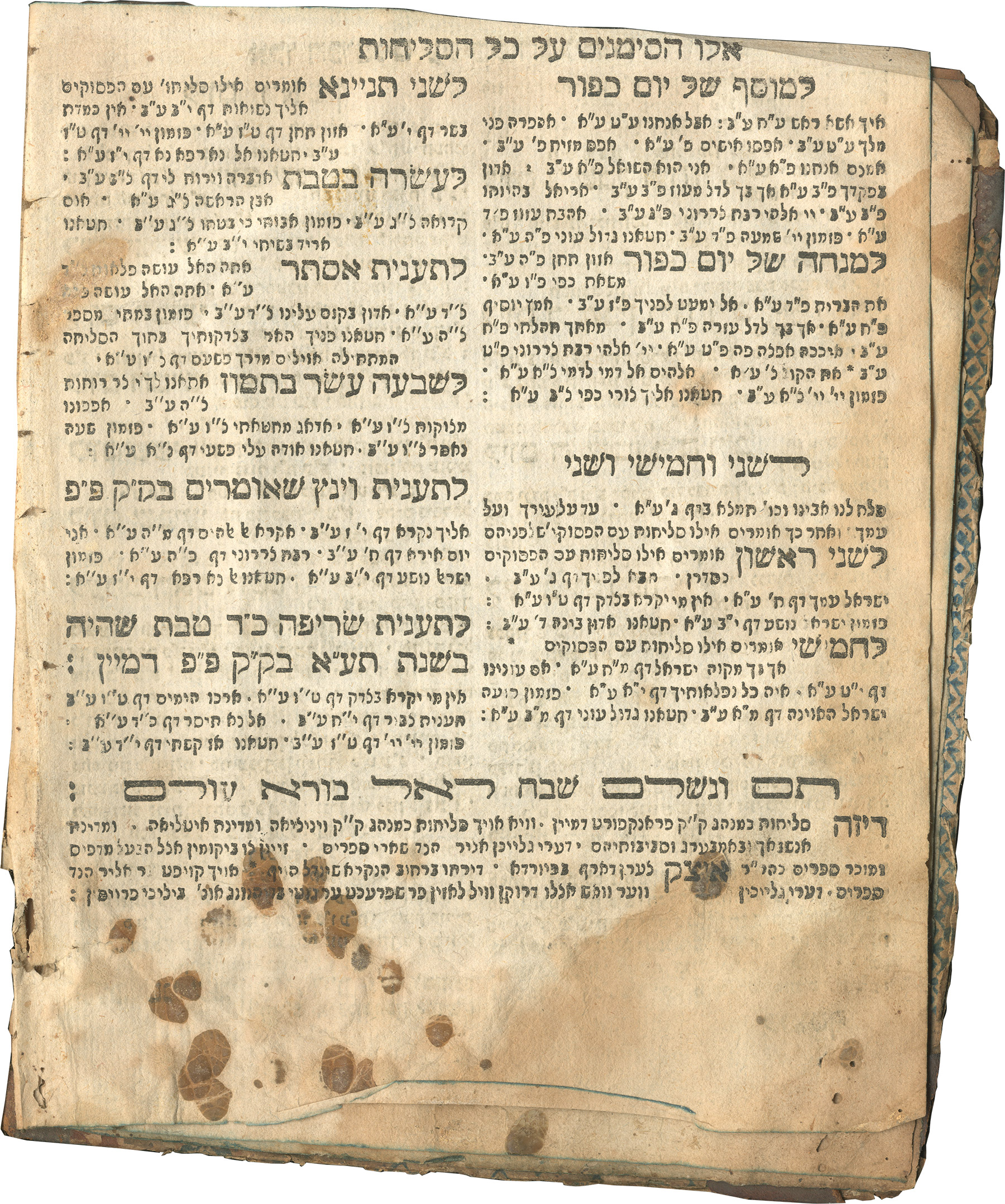

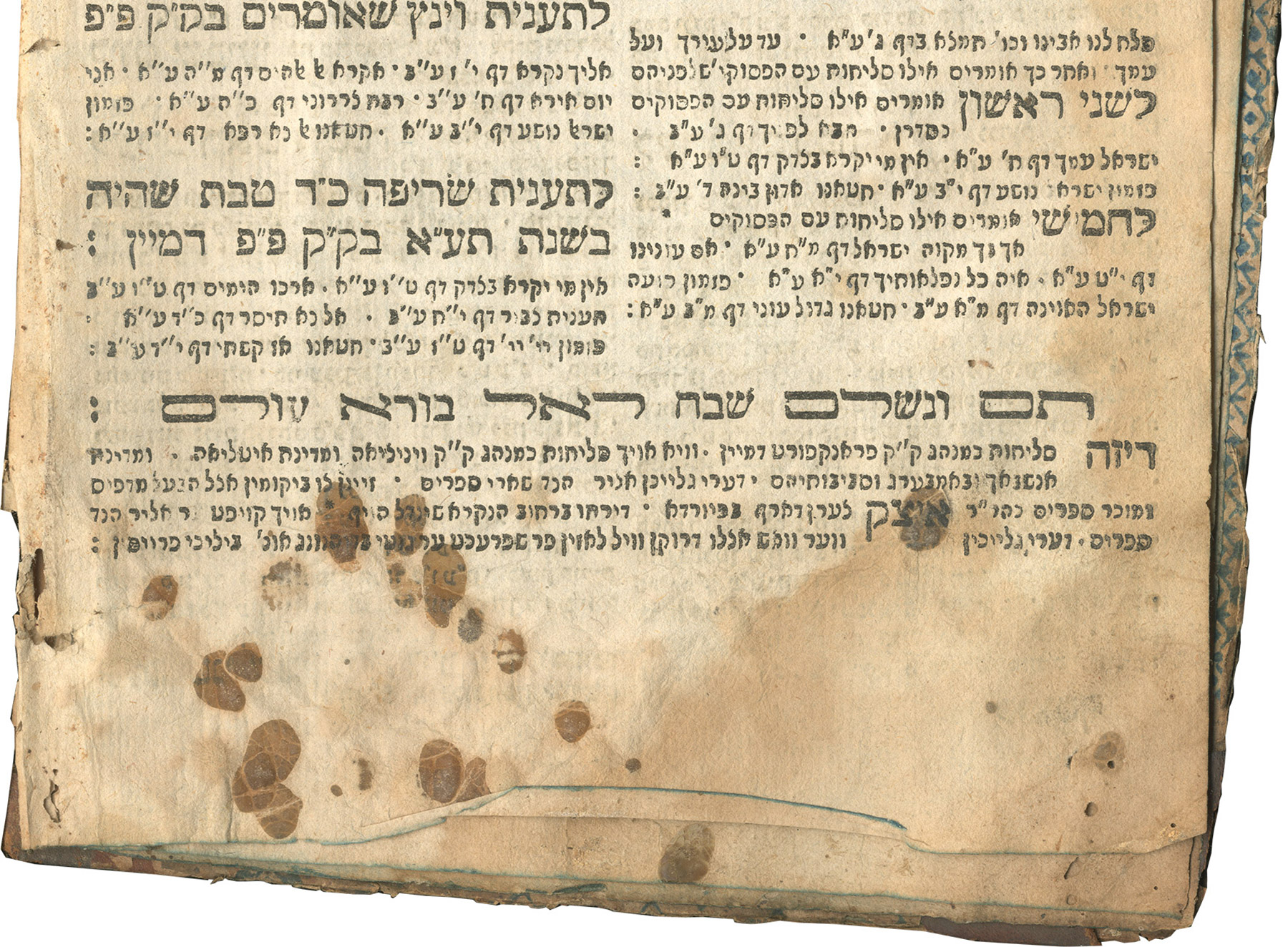

Among the numerous editions of penitential prayers (selihot) owned by the Katz Center Library, there is one following the rite of Frankfurt am Main and published in Fürth in 1787. It forms part of at least twelve editions of six different selihot rites printed in the Franconian city in the 1780s and 1790s. Among these editions, as we learn from an advertisement in the copy at hand, was one following the rite of Venice.

Why would a printing house located in southern Germany have wanted to publish a liturgical work that catered to the Jewish population of Ashkenazi descent living in Italy at the time? That population, after all, although highly invested in preserving its own identity when it first arrived in Italy after the expulsions from most of the German cities in the course of the fifteenth century, had begun to blend into the local scene of Italian-speaking Jews by the end of the sixteenth. The reason why their selihot rite was printed in Fürth two hundred years later is given in the same ad: The Italo-Ashkenazi selihot rite was followed not only in Venice and the Italian lands, but also, and perhaps more importantly, in the Franconian communities of Ansbach and Bamberg. Most likely, the edition printed in Fürth was not meant to be marketed in Italy at all but in an area much closer to home.

How did the Jews of Ansbach and Bamberg come to use the Italo-Ashkenazi selihot rite? In fact, these selihot had been among the first Hebrew books ever printed when they appeared in Piove di Sacco in c. 1475. In the following century, as the new technology spread across Europe, additional selihot editions were published. Remarkably, while Jewish printers in Prague and Krakow each brought their own local rites to the press, the early editions published in the German lands followed the Italian model. It took until 1587 before the selihot rite of the largest community that remained in western Ashkenaz, that of Frankfurt am Main, appeared in print, and another century before it was joined by editions representing the rites of other German communities. Meanwhile, the Jews resettling the towns and villages of early modern Germany had to go by whatever was available.

Bamberg and Ansbach, it seems, had not preserved a local tradition of their own. What made local Jews choose the Italo-Ashkenazi rite we cannot know. However, we do know that they continued to follow that rite well into the nineteenth century. Thus, the selihot edition printed in Fürth testifies to the long-term impact the Ashkenazi diaspora in Italy had on their brethren elsewhere; at the same time, it offers a glimpse into the way the map of medieval Ashkenaz was redrawn in the wake of the transformations