It is hard to overestimate the importance of the first three books of the logical canon known as the Organon

The first three books of the Organon were never translated into Hebrew. Instead, paraphrases of them by the 12th century Muslim philosopher Averroes (Ibn Rushd) were translated from the original Arabic into Hebrew in Naples by Jacob Anatoli in 1232 (together with the next two books of the Organon, the Prior and Posterior Analytics, on syllogistic inference and scientific demonstration, respectively.) Averroes' paraphrases or "Middle Commentaries" of the first three works are extant in over eighty Hebrew manuscripts (and likely more), making them, according to the great literary historian and bibliographer, Moritz Steinschneider, the most popular works in Hebrew written by a non-Jew. They were commented upon by Jewish savants such as Levi Gersonides in the fourteenth century, and Judah Messer Leon in the fifteenth century.

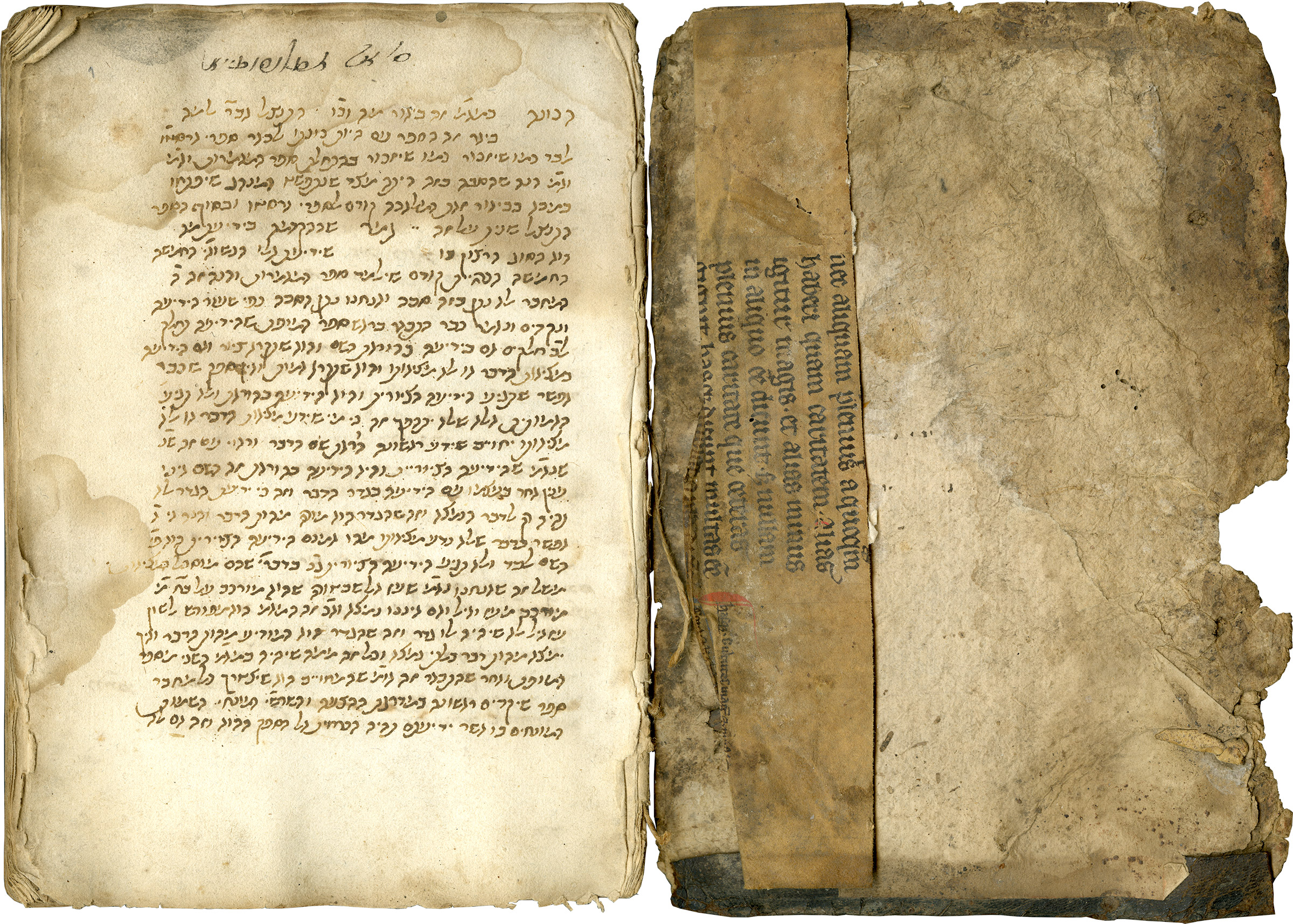

The particular commentary found in the Schoenberg Collection (LJS 229) is anonymous and has not yet been studied. No other copy of it exists, to my knowledge, but the section on the De Interpretatione is found in Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cod. hebr. 46. The commentator refers often to the logical writings of the 10th century Muslim philosopher, Alfarabi, some of which were translated into Hebrew in the late 12th and early 13th century. He also refers to the Arabic version of Averroes' text. But, most interestingly, he cites and criticizes at least once the interpretation of "my teacher, R. Levi," which a cursory comparison of the manuscripts reveals to be Gersonides. If this is correct, then the author of the commentary in LJS 229 was another member of Gersonides' "school," where students read texts with Gersonides and occasionally wrote their own glosses as comments, as has recently been studied by Prof. Ruth Glasner of Hebrew University. Since Gersonides also refers to the Arabic version of Averroes, this manuscript sheds additional light on the methodology employed by members of Gersonides' circle.

As interesting as the anonymous commentary is in itself, the physical codex sheds light on the intellectual life of Provence in the second half of the 15th century. One finds the following statement of ownership in Latin: "Iste liber est meus mestre Benustruc[?] Avidor." This individual may be identified with the 15th century ProvenC'al savant, Avigdor Benastruc, who translated into Hebrew around 1490 the anonymous French Romance of Belle Maguelone, and who wrote a manuscript that included works by the Provencal Jewish scholar, Isaac Nathan, the composer of the first Hebrew concordance of the Bible. If that is the case, it shows that as late as the late fifteenth century, if not later, basic works in Aristotelian logic were studied in Provence, and the influence of Gersonides and his students was still very much felt.