Walking through the florescent lit bookshelves of library stacks is always a pretense. The book one seeks is but an excuse for a treasure hunt in the oversized shelves or the nether reaches of a certain column one has never had reason to tour before. A solitary quest in search of reverie with a hitherto imagined volume has always been the greatest of rewards since my summer job as a young lad retrieving books for callers in the basements of the Hebrew National Library in Jerusalem. The call number is one thing, the trace leading the bookworm

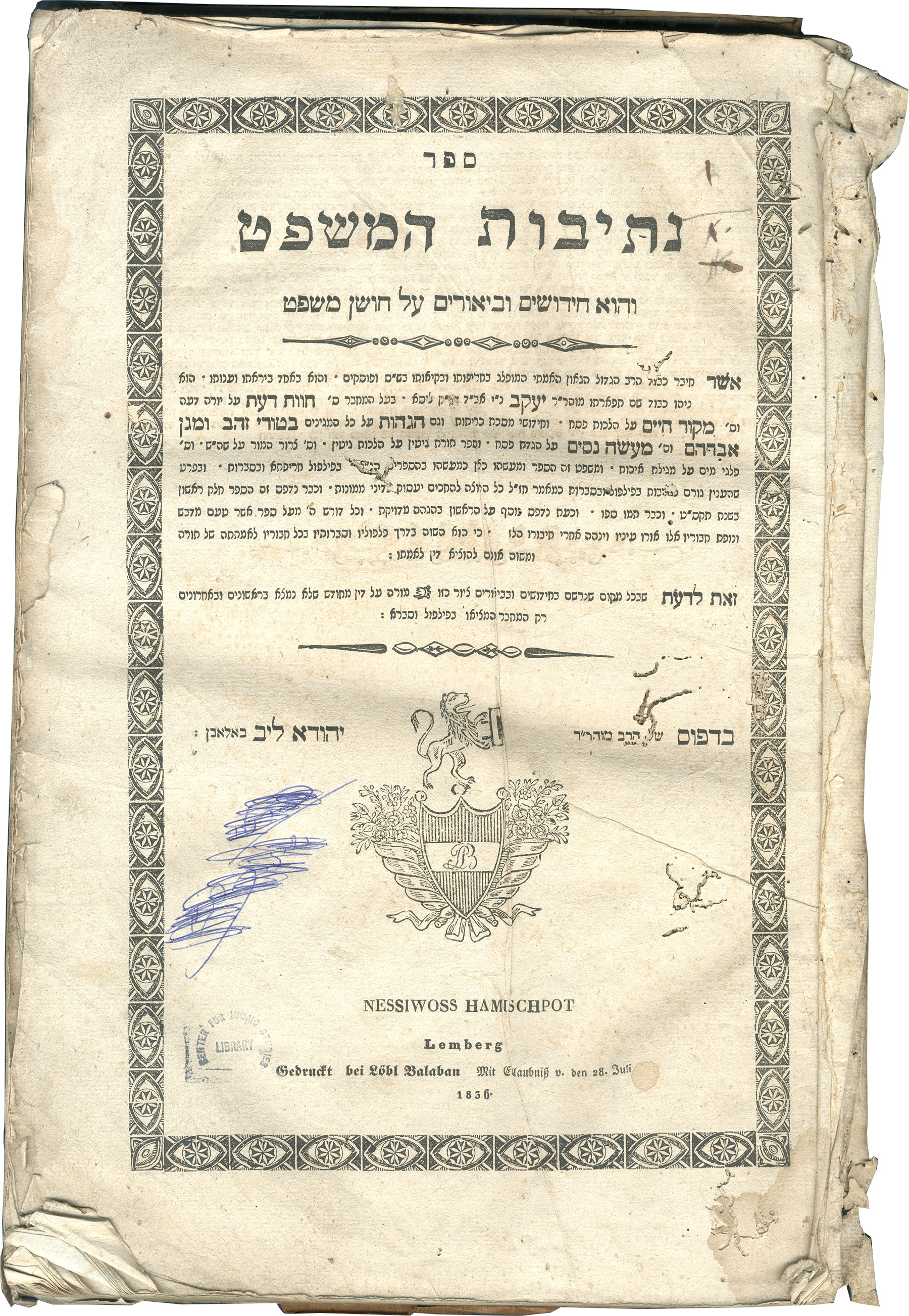

The Katz Center Library showed great promise from the first moment; indeed as soon as I realized that I was free to roam on my own. Then came the day and my eye glanced at a folder in the oversized shelves. A closer look revealed the name Netivot Ha-Mishpat, The Paths of Law, first edition (or what is left of it) by Rabbi Jacob Lorberbaum of Lissa. I pounced upon it. I took the folder and opened it looking at the famed commentary (1809) on the part of the Sulhan Arukh devoted to civil law, Hoshen ha-Mishpat. I made my way through the leaves chancing upon a famed discussion that could have been presented by a legal scholar in our seminar on Jewish political thought, even today, on the nature of representation.

It is clear that one can represent another if appointed to do so

That is, one person may act on behalf of another not present if the outcome is to the latter's benefit. The principle raises crucial questions: What constitutes a benefit? And if it involves acquisition may the latter rescind? Moreover: why? Is representation a matter of bestowing the right of action, of taking one's place, assuming one's power, or is a projected good enough to act on another's behalf (even if unknowingly). Thomas Hobbes uses the term 'personate' to capture the representative relation. Following this insight we can continue pursuing the rabbinic train of thought. In what sense of 'person'? In our physical capacity or our legal capacity as legal agents. Following various talumudic sources Rabbi Jacob's discussion and the retorts of his colleagues suggest that our approach depends on the governing metaphor of representative action: is it an extension of one's hand or of one's competence, power?

At this point, completely lost in thought, I heard the elevator in the background