Conducting archival research, one is often confronted with the pathos of history—the contingencies that render some texts lost or forgotten, while others are remembered and canonized. Moreover, some of the books that we remember bear traces of the circuitous paths by which they made their way into archival collections, while others betray no hints about their provenance, about the chains of scholarly transmission that brought them to the Katz Center.

This year, I devoted most of my time to reading Zionist texts from the first half of the twentieth century. On two occasions, I retrieved books from the stacks only to find that their pages were uncut, suggesting that I was the first person to read the Katz Center’s copy of these works (Hillel Zeitlin, Baruch Spinoza: His Life, Works, and System (1900) [Hebrew] and Hans Kohn, Die Politische Idee des Judentums (1924)). The excitement of discovery was tempered by a sadness that these books had sat unread for so many years.

Several weeks later, I received a copy of Hans Kohn’s History of the Zionist Idea (1929) [Hebrew] from interlibrary loan. On the inside back cover, I found an old circulation card listing the book’s previous borrowers. Only one name was listed—that of Arthur Hertzberg, the editor of the influential anthology of Zionist writings The Zionist Idea (first published in 1959). In many ways, Hertzberg’s project mirrors that of Kohn—both sought to provide a concise introduction to the various schools of Zionist thought. Yet Hertzberg wrote in English, after the establishment of the State of Israel, and, consequently, offers a radically different account of the most influential Zionist thinkers and the most salient ideological debates. I can venture hypotheses as to why Hertzberg was drawn to Kohn’s work and how it may have influenced him, but they remain highly speculative, as the circulation card conveys no information other than the fact that Hertzberg once borrowed the book.

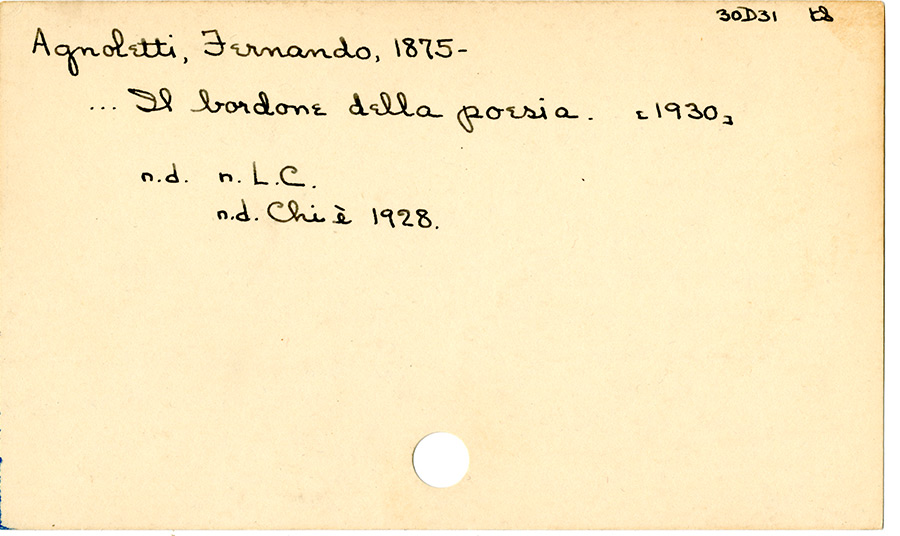

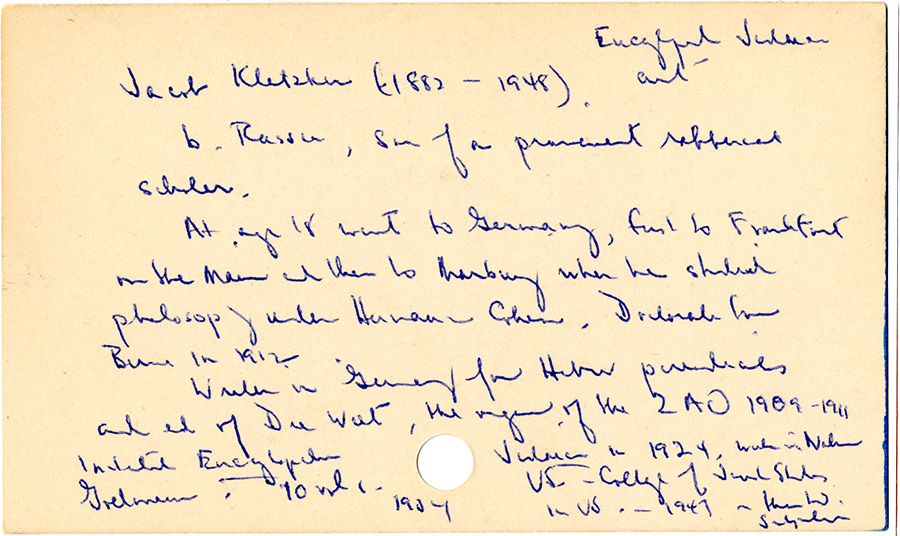

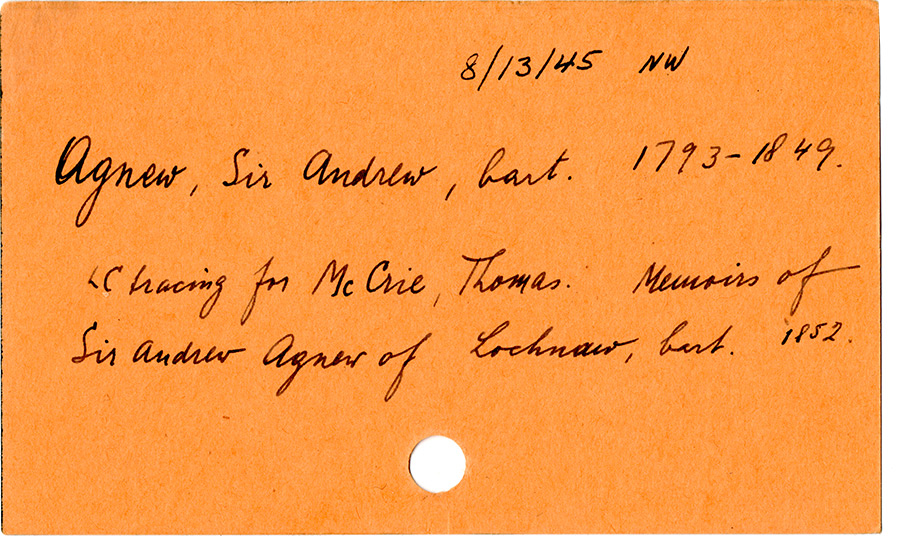

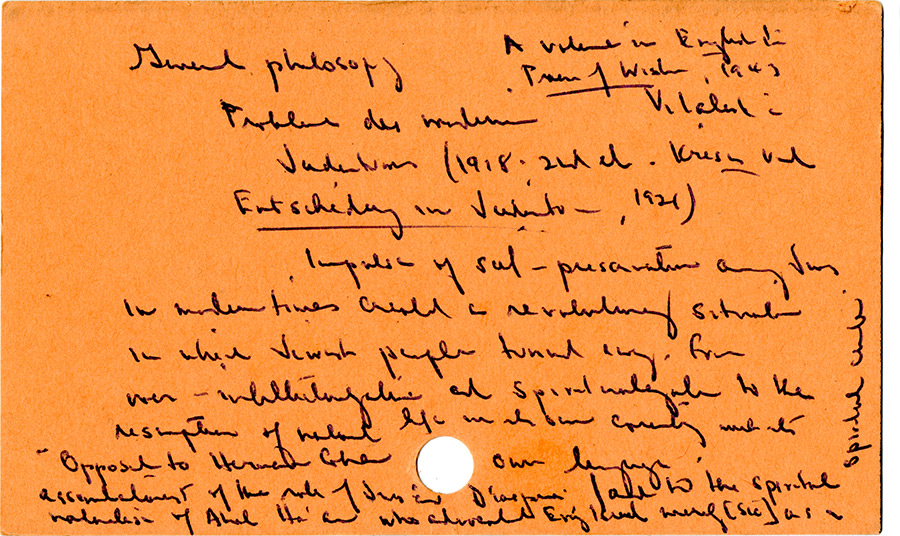

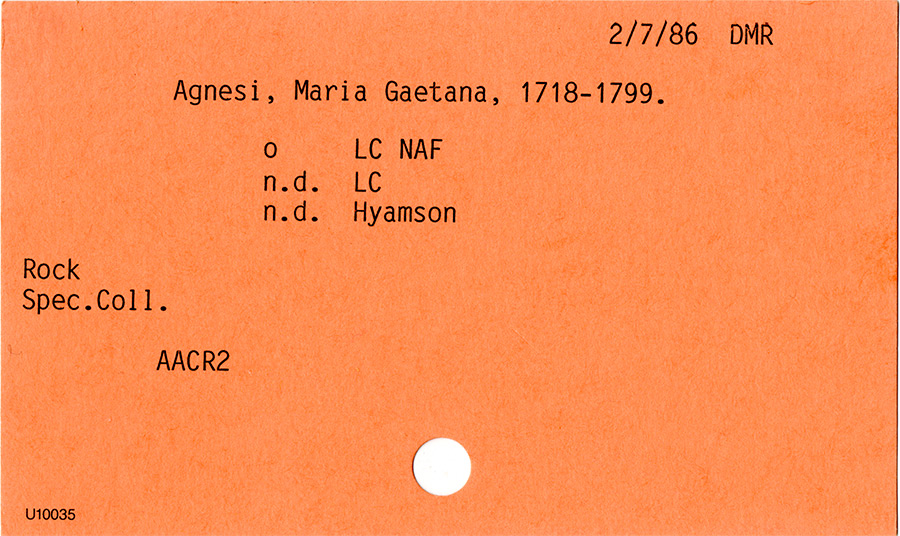

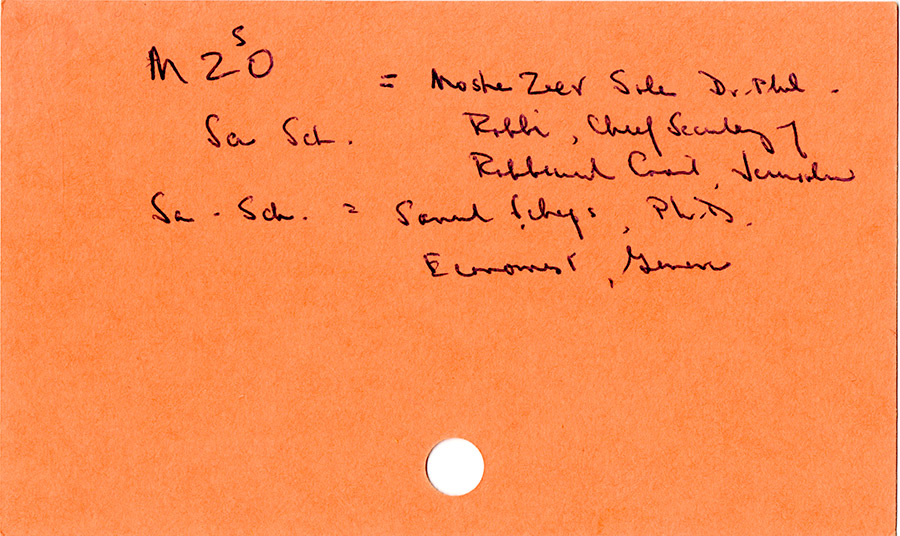

While researching the work of Jacob Klatzkin (1882-1942), however, I stumbled upon unexpected evidence of concrete engagement on the part of at least one of the text’s prior readers. Dedicated to the project of developing a Hebrew philosophical idiom, Klatzkin is best known for his Otzar Ha Munahim Ha Philosophiim (1928) and his Hebrew translation of Spinoza’s Ethics, Torat ha-midot (1924). Some of Klatzkin’s Hebrew philosophical essays and aphorisms were published in English as In Praise of Wisdom (1943). When leafing through a library copy of In Praise of Wisdom, I was surprised to find the three index cards pictured at left—consecutive cards from the “A” drawer of a defunct library card catalogue—left by a prior reader. On the back of these cards from the old card catalogue, the reader has jotted key biographical and bibliographical details about Klatzkin, as well as a brief summary of Klatzkin’s analysis of the modern Jewish predicament and his disputes with his teacher Herman Cohen and with Ahad Ha’am. On the third card, the reader has recorded a shorthand for referring to two other Jewish thinkers from the period, Moshe Zeev Sole and Samuel Scheps. I do not know who jotted these notes or whether his/her research bore fruit, but it is gratifying to think that we are engaged in a serendipitous scholarly conversation about modern Jewish philosophy and political thought. I display the cards here as a testament to my anonymous interlocutor and his/her scholarly contributions.