Modern Jewish Literatures

Judaic Studies 2004-2005 Fellows at the University of Pennsylvania

Designed and edited by

Seth Jerchower

Introduction

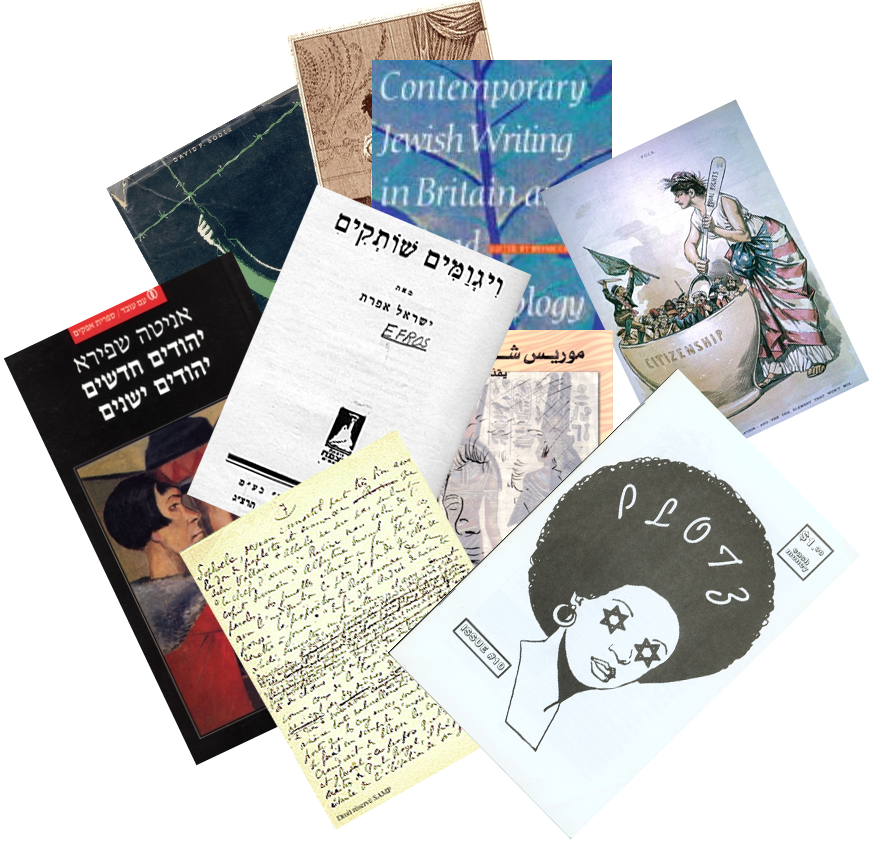

The topics explored in this year’s seminar reflect the enormous diversity of Jewish literature in the modern age. On the one hand, there are literatures in Jewish languages, principally Hebrew, Yiddish and Ladino. On the other, there are Jewish literatures in Russian, German, French, Arabic, English and many other vernacular languages. American Jewish literature, while belonging to the latter category, seems to delimit a sphere of its own reflecting, especially in recent decades, the “difference” of American Jewry. We examined with great interest how in each of these cases the choice of the linguistic medium determines the intended audience and in turn affects the message about Jewish identity and culture. In all instances, we saw literature as a site of intense struggle around the question of Jewishness and modernity in which all the resources of the linguistic imagination were called into play to negotiate the passage from traditional society to contemporary life. What, then, is Jewish literature? Is it one or many? Are there viable criteria for determining what lies within and without the bounds of Jewish literature? These questions, perhaps in the end unanswerable, do not cease to engage us.

Alan Mintz

I Did Not Interview the Dead

David Boder's I Did Not Interview the Dead (U of Illinois Press, 1949) contains eight interviews with displaced persons. A Latvian Jewish émigré to America, Boder traveled to Europe in 1946 to carry out 109 interviews of Holocaust victims--interviews that he conducted in seven languages. Seventy English transcriptions totaling some 3100 pages were eventually brought out by Boder. I Did Not Interview the Dead offered a sample of the massive project. The book jacket displayed here won a graphic arts award for its haunting design.

The interplay between Jewish and non-Jewish languages forms a crucial dimension of Boder's Eastern European origins, education and training; his academic focus on the relation between language and trauma; his aspiration to found a new genre of world literature that he defined, nevertheless, under the rubric of Torah; the complex evolution of the multilingual interviews into a monolingual text; and the puzzling reception of his work, which has relegated the issues of language to the periphery. Boder's focus on language, multilingualism and Jewish notions of tradition and textuality form a key to his approach to Holocaust testimony.

Schmerz der Liebe (Pain of Love)

Rebecca Salomon was born 1783, the daughter of one of the most prominent Jewish bankers and businessmen in Berlin. She married the son of David Friedlaender, one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Berlin, but divorced him after a brief marriage, and began to write and publish popular novels under a pen name, Regina Frohberg. She later took this name as her legal one.

Frohberg, who lived in Berlin and later Vienna, can be considered the first German-Jewish novelist. Most of her fiction deals with the aristocratic milieu, and offers love stories with complicated plot lines; they can be compared to generic Romance novels of today. But some of the plots--as that of the present book, Schmerz der Liebe (Pain of Love)--offered an additional interest for readers in the know. Schmerz der Liebe translated gossip relating to members of the Jewish community into the aristocratic sphere. Thus, Frohberg's work provides an interesting insight into Jewish life around 1800, and her project of assimilation.

Schmerz der Liebe (Pain of Love)

Rebecca Salomon was born 1783, the daughter of one of the most prominent Jewish bankers and businessmen in Berlin. She married the son of David Friedlaender, one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Berlin, but divorced him after a brief marriage, and began to write and publish popular novels under a pen name, Regina Frohberg. She later took this name as her legal one.

Frohberg, who lived in Berlin and later Vienna, can be considered the first German-Jewish novelist. Most of her fiction deals with the aristocratic milieu, and offers love stories with complicated plot lines; they can be compared to generic Romance novels of today. But some of the plots--as that of the present book, Schmerz der Liebe (Pain of Love)--offered an additional interest for readers in the know. Schmerz der Liebe translated gossip relating to members of the Jewish community into the aristocratic sphere. Thus, Frohberg's work provides an interesting insight into Jewish life around 1800, and her project of assimilation.

Rewriting Rebecca

Nineteenth-century historical novels―such as Walter Scott's Ivanhoe (1818), in which the beautiful Rebecca is carried off against her will by a Templar Knight―often depict the foundation of the modern nation state through the persecution of an exoticized Jewess. But what happens when a nineteenth-century Jewish woman writer takes up the genre of historical fiction? Eugénie Foa, née Esther-Rebecca-Eugénie Rodgrigues-Henriques (1796-1853), from a prominent Sephardic family of Bordeaux, wrote a series of historical fictions in the 1830s and 40s from the perspective of Jewish women who struggle to find a place between tradition and modernity, between religious and national identity. The first Jew to write fiction in French, Foa exploited her difference to claim a unique place in the literary field of nineteenth-century France. The popular genre of the historical novel provided her with a means of furthering both her political/ideological agenda―to promote Jewish assimilation in France―and her personal/professional one―to live, against all odds, by her pen.

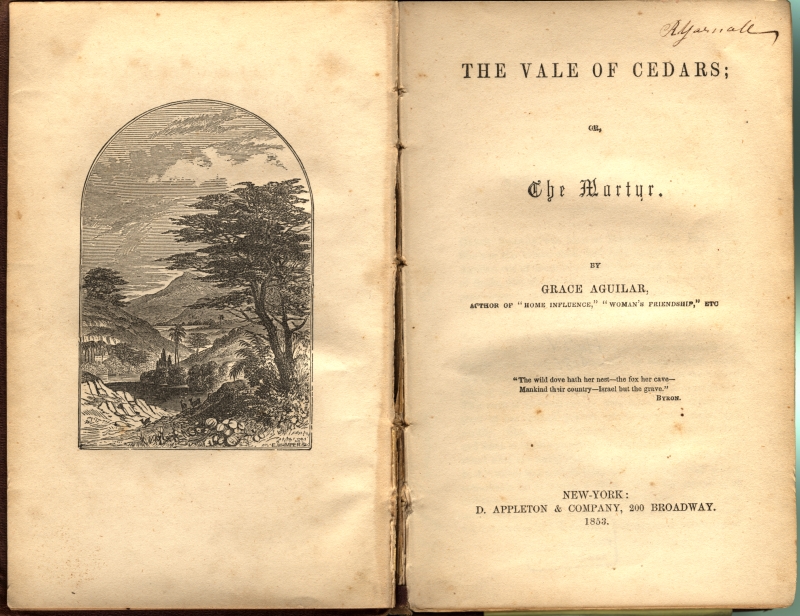

Grace Aguilar's Vale of Cedars

The Vale of Cedars; or, The Martyr, by the Anglo-Jewish novelist and poet Grace Aguilar and published posthumously in 1850, was the first popular English novel on a Jewish historical theme. Written when the author was still in her late teens, the novel displays Aguilar's astute manipulation of the genre of historical romance to serve the cause of Anglo-Jewish religious pride and political emancipation.

Aguilar's novel, set in Inquisition Spain, was designed to appeal to readers of Sir Walter Scott's hugely successful tale of medieval England, Ivanhoe (1819), in focusing on the plight of a beautiful young Jewish woman struggling with her desire for a gentile knight and enduring persecution for resisting conversion to Christianity. The Vale of Cedars, alongside Aguilar's other fictional and devotional writings, was intended to counter the literary efforts of Evangelical conversionists who frequently represented the Jewess as particularly amenable – and susceptible - to conversion. Aguilar's heroine, in contrast, is a crypto-Jewess who passes as a Catholic courtier while remaining loyal to her own religion. Instead of desiring conversion to Christianity, she longs to be liberated from her life of disguise and to embrace Judaism publicly. She was a metaphor for Anglo-Jews who, in early Victorian England, had to choose between religion and citizenship.

Yet in her writing, Aguilar did not so much depart from the model of Evangelical literature as draw upon it. In particular, she utilised a key trope of Evangelical fiction for women: their reverence for femininity, female companionship, and female moral force. In The Vale of Cedars, the heroine, pursued and tortured by the Inquisition, is (with implausible poetic license) protected by the maternal figure of Queen Isabella. The Queen reproaches her courtiers for their disapproval of her compassion for Marie: 'Has every spark of woman's nature faded from your hearts, that ye can speak thus? ... Detest, abhor, avoid her faith - for that we command thee; but her sex, her sorrow, have a claim to sympathy and aid, which not even her race can remove'. In Aguilar's fiction, differences of 'faith' or 'race' could be transcended by the universalist ideology of femininity.

Grace Aguilar's Vale of Cedars

The Vale of Cedars; or, The Martyr, by the Anglo-Jewish novelist and poet Grace Aguilar and published posthumously in 1850, was the first popular English novel on a Jewish historical theme. Written when the author was still in her late teens, the novel displays Aguilar's astute manipulation of the genre of historical romance to serve the cause of Anglo-Jewish religious pride and political emancipation.

Aguilar's novel, set in Inquisition Spain, was designed to appeal to readers of Sir Walter Scott's hugely successful tale of medieval England, Ivanhoe (1819), in focusing on the plight of a beautiful young Jewish woman struggling with her desire for a gentile knight and enduring persecution for resisting conversion to Christianity. The Vale of Cedars, alongside Aguilar's other fictional and devotional writings, was intended to counter the literary efforts of Evangelical conversionists who frequently represented the Jewess as particularly amenable – and susceptible - to conversion. Aguilar's heroine, in contrast, is a crypto-Jewess who passes as a Catholic courtier while remaining loyal to her own religion. Instead of desiring conversion to Christianity, she longs to be liberated from her life of disguise and to embrace Judaism publicly. She was a metaphor for Anglo-Jews who, in early Victorian England, had to choose between religion and citizenship.

Yet in her writing, Aguilar did not so much depart from the model of Evangelical literature as draw upon it. In particular, she utilised a key trope of Evangelical fiction for women: their reverence for femininity, female companionship, and female moral force. In The Vale of Cedars, the heroine, pursued and tortured by the Inquisition, is (with implausible poetic license) protected by the maternal figure of Queen Isabella. The Queen reproaches her courtiers for their disapproval of her compassion for Marie: 'Has every spark of woman's nature faded from your hearts, that ye can speak thus? ... Detest, abhor, avoid her faith - for that we command thee; but her sex, her sorrow, have a claim to sympathy and aid, which not even her race can remove'. In Aguilar's fiction, differences of 'faith' or 'race' could be transcended by the universalist ideology of femininity.

Pax Vobiscum

More than a pen-name, Sholem Aleichem is the alter-ego, or literary persona, of Sholem Rabinovitsh (1859-1916), who through this creation has become known as the greatest Yiddish writer, and the most outstanding humorist in modern Jewish literature. The name "Sholem Aleichem" itself means, alternately, "Peace Be Unto You" or "How d'you do" it's a greeting offered in Yiddish, and Hebrew, to a familiar person with whom one is nonetheless not in constant contact. "Sholem Aleichem" is not a daily greeting, like "hello" or "good afternoon," but rather the greeting offered to a person one hasn't seen in several days. As a pseudonym or alternate identity, it thus suggests familiarity and distance at one and the same time, and this combination is essential to Sholem Aleichem's enduring popularity, as well as his deceptively satirical comic vision.

Among his many achievements, Sholem Aleichem must rank among the most prolific figures in modern Jewish literature; the standard edition of his "complete" works runs to 28 volumes, and even this collection is marred by several glaring omissions. His most famous and critically regarded narratives include Tevye the Milkman, The Letters of Menakhem-Mendl and Sheyne-Sheyndl, Motl the Cantor Peyse's Son, and the Railroad Stories. Although Sholem Aleichem began his career with the aspiration of creating for Yiddish literature something analogous to Honoré de Balzac's Comédie humaine--a grand cycle of realist novels portraying a civilization in its entirety--the works on which his reputation rests are in fact sequences of monologues (or in the case of the Menakhem-Mendl sequence, letters that read like monologues) narrated typically by marginal figures with an incomplete understanding of their situation. Their literary quality derives from the author's mastery of a super-idiomatic Yiddish that sounds like everyday speech, but evokes tragicomic echoes of traditional Jewish learning, juxtaposed against the fragmentation and confusion of Jewish Eastern Europe in the midst of industrial modernization, political instability, and mass emigration.

In addition to the best known and most canonical of Sholem Aleichem's tale sequences, another series of stories meriting reappraisal is the group of satirical tales he wrote describing the general character of life in the fictional shtetl Kasrilevke. Although most contemporary critics have focused their attention to Sholem Aleichem on the most explicitly dynamic narratives in his body of work, the Kasrilevke stories reiterate exhaustively--and to considerable comic effect--the essentially static, immobile aspects of traditional Jewish life. When taken as a particular genre, the Kasrilevke stories evoke not only a location, but an inverted presence, a revocation of the dynamism that characterizes Jewish modernity and Sholem Aleichem's (or rather, Rabinovitsh's) political convictions. The Kasrilevke sequence therefore presents a rejoinder to the ideological ferment of early-20th century Eastern European life. How Sholem Aleichem conceptualizes this space is a crucial issue because precisely the control of space, territory, is the central preoccupation of all the modern ideologies to which the Kasrilevke stories obliquely and subversively respond.

Pax Vobiscum

More than a pen-name, Sholem Aleichem is the alter-ego, or literary persona, of Sholem Rabinovitsh (1859-1916), who through this creation has become known as the greatest Yiddish writer, and the most outstanding humorist in modern Jewish literature. The name "Sholem Aleichem" itself means, alternately, "Peace Be Unto You" or "How d'you do" it's a greeting offered in Yiddish, and Hebrew, to a familiar person with whom one is nonetheless not in constant contact. "Sholem Aleichem" is not a daily greeting, like "hello" or "good afternoon," but rather the greeting offered to a person one hasn't seen in several days. As a pseudonym or alternate identity, it thus suggests familiarity and distance at one and the same time, and this combination is essential to Sholem Aleichem's enduring popularity, as well as his deceptively satirical comic vision.

Among his many achievements, Sholem Aleichem must rank among the most prolific figures in modern Jewish literature; the standard edition of his "complete" works runs to 28 volumes, and even this collection is marred by several glaring omissions. His most famous and critically regarded narratives include Tevye the Milkman, The Letters of Menakhem-Mendl and Sheyne-Sheyndl, Motl the Cantor Peyse's Son, and the Railroad Stories. Although Sholem Aleichem began his career with the aspiration of creating for Yiddish literature something analogous to Honoré de Balzac's Comédie humaine--a grand cycle of realist novels portraying a civilization in its entirety--the works on which his reputation rests are in fact sequences of monologues (or in the case of the Menakhem-Mendl sequence, letters that read like monologues) narrated typically by marginal figures with an incomplete understanding of their situation. Their literary quality derives from the author's mastery of a super-idiomatic Yiddish that sounds like everyday speech, but evokes tragicomic echoes of traditional Jewish learning, juxtaposed against the fragmentation and confusion of Jewish Eastern Europe in the midst of industrial modernization, political instability, and mass emigration.

In addition to the best known and most canonical of Sholem Aleichem's tale sequences, another series of stories meriting reappraisal is the group of satirical tales he wrote describing the general character of life in the fictional shtetl Kasrilevke. Although most contemporary critics have focused their attention to Sholem Aleichem on the most explicitly dynamic narratives in his body of work, the Kasrilevke stories reiterate exhaustively--and to considerable comic effect--the essentially static, immobile aspects of traditional Jewish life. When taken as a particular genre, the Kasrilevke stories evoke not only a location, but an inverted presence, a revocation of the dynamism that characterizes Jewish modernity and Sholem Aleichem's (or rather, Rabinovitsh's) political convictions. The Kasrilevke sequence therefore presents a rejoinder to the ideological ferment of early-20th century Eastern European life. How Sholem Aleichem conceptualizes this space is a crucial issue because precisely the control of space, territory, is the central preoccupation of all the modern ideologies to which the Kasrilevke stories obliquely and subversively respond.

The Melting Pot

Cauldrons and crucibles existed as symbols of immigration well before Anglo-Jewish novelist and playwright Israel Zangwill penned his popular melodrama, The Melting Pot, first staged in 1908. In this Puck cartoon of 1889, 'The Mortar of Assimilation ― and the One Element that Won't Mix, Lady Liberty stirs the tub of citizenship, and a recalicitrant Irish revolutionary dances on the rim.

But it was Zangwill's play that made the melting pot the central term in the discourse of immigration and assimilation. Lauded by President Theodore Roosevelt and denounced by countless American rabbis, The Melting Pot dramatizes the ideal of Americanzation in the love-conquers-all story of David Quixano, a young Russian Jewish musician whose family was killed in the Kishinev pogrom, and Vera Revendal, a beautiful Russian Christian whose father masterminded the massacre. Ironically, the one element that doesn't mix in the play is not an immigrant but Quincy Davenport, a descendant of the Puritan founders and David's mirror opposite, whose decadence and immorality make him unfit to inherit his ancestors' legacy.

À la recherche du juif perdu

Yosef Yerushalmi tells the story of his discovery, in the Sigmund Freud Archives in Washington DC, of the family Bible that Freud's father Jakob first inscribed, in Hebrew, on the occasion of Sigmund Freud's circumcision. Thirty-five years later, the elder Freud had the volume re-bound in leather, and he added a dedication to his son, by hand and in Hebrew, composed as a melitzah―a traditional genre in Hebrew letters consisting of an arrangement of textual bits drawn from the Bible and other Jewish sources. Yerushalmi appears to believe―though he does not insist―that this dedication offers strong evidence of the Freud's ability to read and understand Hebrew, Freud's statements to the contrary notwithstanding. Yerushalmi calls Freud's writing of Moses and Monotheism an act of "'deferred obedience'" to a paternal "'mandate.'" The melitzah written by Jakob Freud in 1896 directed Sigmund to return to the book and to reengage his Jewish origins. At a distance of thirty-eight years, the son obeyed the father by radically rewriting the history that constitutes and preserves the Jews as a people. How, we might wonder, would his father, the author of the melitzah, have received Moses and Monotheism in fulfillment of his mandate? Yerushalmi thinks that Jakob Freud "would not have been displeased." One thing seems clear, however. If Moses and Monotheism may be understood as a satisfactory fulfillment of a mandate to return to Jewish history and origins, then obedience, in this context, does not preclude subversion.

In Proust, remarkably, many of these same elements are present. Proust's Charles Swann is a paradigm of assimilation, especially in the French context, where assimilation is best measured by the standard of the severest gatekeepers of francité (Frenchness): the high aristocracy. The vexed question of Swann's Jewishness is definitely resolved in Sodome et Gomorrhe when, at the height of the Dreyfus Affair, the narrator describes him as degrading facially to the point where he resembles an "old Hebrew rather than a dilettante Valois." Nearing death, Swann returns "to the spiritual fold of his fathers" ['au bercail religieux de ses pères'] and arrives "at the age of the prophet."

If Swann is thus like Sigmund Freud, a Jew whose Judaism may be "terminated," but whose Jewishness appears "interminable," he is also strangely like Jakob. For he is the one who implicitly also issues the mandate, to his daughter Gilberte: remember your Jewish father. A mandate like his is a variant, to be sure, of what Yerushalmi has called the "injunction to remember"―regarded "[o]nly in Israel and nowhere else . . . as a religious imperative to an entire people." Does Gilberte fulfill the mandate? Does she carry out an act of "deferred obedience"? Does she make her own confession? The answer to all these questions must be yes: subversively. Gilberte profanes the memory of the Jewish father, much as Freud profanes sacred Jewish history, in subversive obedience to a mandate to acknowledge and engage Jewish origins. Perhaps like Freud, she also makes a confession, which has not survived, though its traces abound, in the archives.

À la recherche du juif perdu

Yosef Yerushalmi tells the story of his discovery, in the Sigmund Freud Archives in Washington DC, of the family Bible that Freud's father Jakob first inscribed, in Hebrew, on the occasion of Sigmund Freud's circumcision. Thirty-five years later, the elder Freud had the volume re-bound in leather, and he added a dedication to his son, by hand and in Hebrew, composed as a melitzah―a traditional genre in Hebrew letters consisting of an arrangement of textual bits drawn from the Bible and other Jewish sources. Yerushalmi appears to believe―though he does not insist―that this dedication offers strong evidence of the Freud's ability to read and understand Hebrew, Freud's statements to the contrary notwithstanding. Yerushalmi calls Freud's writing of Moses and Monotheism an act of "'deferred obedience'" to a paternal "'mandate.'" The melitzah written by Jakob Freud in 1896 directed Sigmund to return to the book and to reengage his Jewish origins. At a distance of thirty-eight years, the son obeyed the father by radically rewriting the history that constitutes and preserves the Jews as a people. How, we might wonder, would his father, the author of the melitzah, have received Moses and Monotheism in fulfillment of his mandate? Yerushalmi thinks that Jakob Freud "would not have been displeased." One thing seems clear, however. If Moses and Monotheism may be understood as a satisfactory fulfillment of a mandate to return to Jewish history and origins, then obedience, in this context, does not preclude subversion.

In Proust, remarkably, many of these same elements are present. Proust's Charles Swann is a paradigm of assimilation, especially in the French context, where assimilation is best measured by the standard of the severest gatekeepers of francité (Frenchness): the high aristocracy. The vexed question of Swann's Jewishness is definitely resolved in Sodome et Gomorrhe when, at the height of the Dreyfus Affair, the narrator describes him as degrading facially to the point where he resembles an "old Hebrew rather than a dilettante Valois." Nearing death, Swann returns "to the spiritual fold of his fathers" ['au bercail religieux de ses pères'] and arrives "at the age of the prophet."

If Swann is thus like Sigmund Freud, a Jew whose Judaism may be "terminated," but whose Jewishness appears "interminable," he is also strangely like Jakob. For he is the one who implicitly also issues the mandate, to his daughter Gilberte: remember your Jewish father. A mandate like his is a variant, to be sure, of what Yerushalmi has called the "injunction to remember"―regarded "[o]nly in Israel and nowhere else . . . as a religious imperative to an entire people." Does Gilberte fulfill the mandate? Does she carry out an act of "deferred obedience"? Does she make her own confession? The answer to all these questions must be yes: subversively. Gilberte profanes the memory of the Jewish father, much as Freud profanes sacred Jewish history, in subversive obedience to a mandate to acknowledge and engage Jewish origins. Perhaps like Freud, she also makes a confession, which has not survived, though its traces abound, in the archives.

Beyond the Purim Shpil

The title page of a prayer in verse by a woman poet, Toybe Pan, published in Prague in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, this long poem is entitled, 'Eyn sheyn lid naye gimakht/ beloshn tkhine iz vardin oys gitrakht' (A Brand-New Beautiful Song/ Composed in the Tkhine-Tongue). Unlike most tkhines―supplicatory Yiddish prayers for women to say individually―Toybe Pan's poem seems to have been intended for public recitation, by men as well as women, at a particular moment of communal crisis. Asking God to rescue the Jews of Prague from a plague afflicting their region, Toybe Pan subtly likens herself to Queen Esther, who rescued the Jews of Persia.

Title page and concluding page of a 1917 Yiddish poem by Moyshe Broderzon, Sikhes Khulin (Small Talk), illustrated by Eliezar Lissitzky. This work, which parodies a medieval chronicle of the Jewish community of Prague , was an early attempt to formulate a modern Jewish idea of art. Physically, Sikhes Khulin resembles a Scroll of Esther, read by Jews on Purim, in that Broderzon's text was inscribed by hand, as by a sofer (Jewish scribe), and a few hand-colored copies of the small edition were presented in the form of a scroll. By presenting a modern Yiddish verse parody of a medieval Jewish chronicle in the physical form of an ancient Hebrew sacred text, Broderzon and Lissitzky reconfigure the sacred as secular and the traditional as modern in order to tell a new Jewish story.

This is the only extant photograph of the Lodz Yiddish poet, Miriam Ulinover (Lodz 1890-Auschwitz, 1944), whose 1922 poem, 'Ester hamalke' (Esther the Queen) casts a shtetl maiden in the role of Esther at a synagogue Purim celebration. In Ulinover's deliberately old-fashioned, folk-like diction and verse form, the girl saves herself from a modern alienation and, through the fantasy of herself as the ancient, heroic queen, contrasts the folk culture of a shtetl grandmother with the urbane literary culture of Ulinover's readers.

ESTHER THE QUEEN

(Warsaw, 1922)

When the gregger knocks and rattles,

You can hardly hear a word―

I won't allow you people

To chase away my dream!

My skirt, plain calico,

Swaying to and fro―

Turns into actual

Crimson frill and bow.

The thin red ribbon

Looped around my braid

Will with royal scarlet

Crown my head.

Somehow, my face grows

Charming and dark…

Like Esther the Queen!―

A still smile in my heart.

And I blossom forth in beauty,

And my dream's on fire―

I am the queen, the queen!

And, to raise me higher,

Now the king bequests

Half the kingdom's land―

I am Queen Esther

Beneath the purple band.

Translation © 2005 Kathryn Hellerstein

All Rights Reserved

ESTER HAMALKA

Beyond the Purim Shpil

The title page of a prayer in verse by a woman poet, Toybe Pan, published in Prague in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, this long poem is entitled, 'Eyn sheyn lid naye gimakht/ beloshn tkhine iz vardin oys gitrakht' (A Brand-New Beautiful Song/ Composed in the Tkhine-Tongue). Unlike most tkhines―supplicatory Yiddish prayers for women to say individually―Toybe Pan's poem seems to have been intended for public recitation, by men as well as women, at a particular moment of communal crisis. Asking God to rescue the Jews of Prague from a plague afflicting their region, Toybe Pan subtly likens herself to Queen Esther, who rescued the Jews of Persia.

Title page and concluding page of a 1917 Yiddish poem by Moyshe Broderzon, Sikhes Khulin (Small Talk), illustrated by Eliezar Lissitzky. This work, which parodies a medieval chronicle of the Jewish community of Prague , was an early attempt to formulate a modern Jewish idea of art. Physically, Sikhes Khulin resembles a Scroll of Esther, read by Jews on Purim, in that Broderzon's text was inscribed by hand, as by a sofer (Jewish scribe), and a few hand-colored copies of the small edition were presented in the form of a scroll. By presenting a modern Yiddish verse parody of a medieval Jewish chronicle in the physical form of an ancient Hebrew sacred text, Broderzon and Lissitzky reconfigure the sacred as secular and the traditional as modern in order to tell a new Jewish story.

This is the only extant photograph of the Lodz Yiddish poet, Miriam Ulinover (Lodz 1890-Auschwitz, 1944), whose 1922 poem, 'Ester hamalke' (Esther the Queen) casts a shtetl maiden in the role of Esther at a synagogue Purim celebration. In Ulinover's deliberately old-fashioned, folk-like diction and verse form, the girl saves herself from a modern alienation and, through the fantasy of herself as the ancient, heroic queen, contrasts the folk culture of a shtetl grandmother with the urbane literary culture of Ulinover's readers.

ESTHER THE QUEEN

(Warsaw, 1922)

When the gregger knocks and rattles,

You can hardly hear a word―

I won't allow you people

To chase away my dream!

My skirt, plain calico,

Swaying to and fro―

Turns into actual

Crimson frill and bow.

The thin red ribbon

Looped around my braid

Will with royal scarlet

Crown my head.

Somehow, my face grows

Charming and dark…

Like Esther the Queen!―

A still smile in my heart.

And I blossom forth in beauty,

And my dream's on fire―

I am the queen, the queen!

And, to raise me higher,

Now the king bequests

Half the kingdom's land―

I am Queen Esther

Beneath the purple band.

Translation © 2005 Kathryn Hellerstein

All Rights Reserved

ESTER HAMALKA

Beyond the Purim Shpil

The title page of a prayer in verse by a woman poet, Toybe Pan, published in Prague in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, this long poem is entitled, 'Eyn sheyn lid naye gimakht/ beloshn tkhine iz vardin oys gitrakht' (A Brand-New Beautiful Song/ Composed in the Tkhine-Tongue). Unlike most tkhines―supplicatory Yiddish prayers for women to say individually―Toybe Pan's poem seems to have been intended for public recitation, by men as well as women, at a particular moment of communal crisis. Asking God to rescue the Jews of Prague from a plague afflicting their region, Toybe Pan subtly likens herself to Queen Esther, who rescued the Jews of Persia.

Title page and concluding page of a 1917 Yiddish poem by Moyshe Broderzon, Sikhes Khulin (Small Talk), illustrated by Eliezar Lissitzky. This work, which parodies a medieval chronicle of the Jewish community of Prague , was an early attempt to formulate a modern Jewish idea of art. Physically, Sikhes Khulin resembles a Scroll of Esther, read by Jews on Purim, in that Broderzon's text was inscribed by hand, as by a sofer (Jewish scribe), and a few hand-colored copies of the small edition were presented in the form of a scroll. By presenting a modern Yiddish verse parody of a medieval Jewish chronicle in the physical form of an ancient Hebrew sacred text, Broderzon and Lissitzky reconfigure the sacred as secular and the traditional as modern in order to tell a new Jewish story.

This is the only extant photograph of the Lodz Yiddish poet, Miriam Ulinover (Lodz 1890-Auschwitz, 1944), whose 1922 poem, 'Ester hamalke' (Esther the Queen) casts a shtetl maiden in the role of Esther at a synagogue Purim celebration. In Ulinover's deliberately old-fashioned, folk-like diction and verse form, the girl saves herself from a modern alienation and, through the fantasy of herself as the ancient, heroic queen, contrasts the folk culture of a shtetl grandmother with the urbane literary culture of Ulinover's readers.

ESTHER THE QUEEN

(Warsaw, 1922)

When the gregger knocks and rattles,

You can hardly hear a word―

I won't allow you people

To chase away my dream!

My skirt, plain calico,

Swaying to and fro―

Turns into actual

Crimson frill and bow.

The thin red ribbon

Looped around my braid

Will with royal scarlet

Crown my head.

Somehow, my face grows

Charming and dark…

Like Esther the Queen!―

A still smile in my heart.

And I blossom forth in beauty,

And my dream's on fire―

I am the queen, the queen!

And, to raise me higher,

Now the king bequests

Half the kingdom's land―

I am Queen Esther

Beneath the purple band.

Translation © 2005 Kathryn Hellerstein

All Rights Reserved

ESTER HAMALKA

Khad gadye le-El

The facsimile edition of Eliezer Lissitzky's HAD GADYA published by the Getty Museum (2004) is a rare recuperation of an important Jewish book that has almost disappeared. Only 75 copies were published in the Soviet Union in 1919 and most have been lost since then. This magnificent collection of this Russian Jewish artist's graphic interpretations of each verse of the well-known song found at the end of the traditional Passover Haggadah is a significant, moving and enigmatic testimony of the beginning the end of Jewish culture in the Soviet Union. The artist produced this series of whimsical illustrations in a modernistic style leading up to a statement of support of the Revolution in the last frame, but the reader cannot escape the hidden suggestion conveyed by the Yiddish usage of the term "Khad gadye" meaning "jail." After this series of illustrations, Lissitzky never again signed his work with his full Jewish name, Eliezer, but truncated it to El Lissitzky.

Khad gadye le-El

The facsimile edition of Eliezer Lissitzky's HAD GADYA published by the Getty Museum (2004) is a rare recuperation of an important Jewish book that has almost disappeared. Only 75 copies were published in the Soviet Union in 1919 and most have been lost since then. This magnificent collection of this Russian Jewish artist's graphic interpretations of each verse of the well-known song found at the end of the traditional Passover Haggadah is a significant, moving and enigmatic testimony of the beginning the end of Jewish culture in the Soviet Union. The artist produced this series of whimsical illustrations in a modernistic style leading up to a statement of support of the Revolution in the last frame, but the reader cannot escape the hidden suggestion conveyed by the Yiddish usage of the term "Khad gadye" meaning "jail." After this series of illustrations, Lissitzky never again signed his work with his full Jewish name, Eliezer, but truncated it to El Lissitzky.

V. Laykhter's Orthodox Expressionist Poetry

In the early 1920s, the religious poet V. Laykhter published a number of Yiddish poems in a style best described as Orthodox expressionism. The image displayed below is part of one of these poems (click on the image for full text and translation).

Laykhter (pseudonym of Meyer Voydislavski) was born in 1904 into a well-to-do Hasidic family in Lodz , Poland . He spent the years of the First World War in Russia , and it is likely that he encountered avant-garde poetics there. When he returned to Lodz after the war, he became active in the Orthodox political party Agudes Yisroel, helping to found its youth wing, then known as "Tseirey Emuney Yisroel" ("The Youth of the Faithful of Israel"). He also founded an Orthodox publishing house, Sgule, and an Orthodox Yiddish journal Ortodoksishe bletlekh (Orthodox Pages), that he edited himself and that appeared between 1922 and 1924. In 1925 he immigrated to Palestine where he continued to write both in Hebrew and in Yiddish for the Orthodox press both in Palestine and in Poland . He died in Tel Aviv in 1945 of a heart attack.

It is important to note that these activities were novel, even revolutionary, in the Orthodox sphere in Poland in the early years of the interwar period. Laykhter was involved in the formation of the institutions of organized Orthodoxy in Poland in a period in which new norms for a traditional way of life in the modern world were being set, and the parameters of an Orthodox lifestyle still very fluid. With his unique Orthodox expressionism, however, Laykhter pushed what was acceptable within Orthodox circles to the limit. At the root of expressionism, the dominant style in (secular) Yiddish poetry at the time, was Nietzsche's pronouncement that "God is dead" and the perception that the world was in a state of collapse. This stance is clearly antithetical to a religious world view, and yet Laykhter managed to convey the feeling of chaos and collapse that came to head in the First World War within a framework of faith.

The poem reproduced here, "Dos geshrey fun a stam in lerkayt fun velt" ("Someone's Cry in the Emptiness of World"), most clearly illustrates how Laykhter was able to use the expressionist aesthetic while at the same time asserting belief in God. The last few lines create a framework of faith, a simple faith in one God no matter what, that frees the poet to explore his relationship with a violent, fragmented world without the denial of God that the aesthetic implies. The poem does not, however, lend itself to a simple interpretation. Although the speaker clearly states his faith, the tension between the tormented bulk of the poem and its pious ending suggests that this faith has been shaken, and that it is only through an act of intellectual abstraction ("alef=one― / one God in the world") that the overwhelming sense of despair can be held in check.

Antologye fun religyeze lider un dertseylungen : shafungen fun shrayber, umgekumene in di yorn fun Yidishn hurbn in Eyrope / tsuzamengeshtelt fun Mosheh Prager. Nyu-York : Forshungs-Institut fun religyezn Yidntum, 1955. (Anthology of Jewish poems, stories and essays : written by religious authors, victims of Nazi persecution)

V. Laykhter's Orthodox Expressionist Poetry

In the early 1920s, the religious poet V. Laykhter published a number of Yiddish poems in a style best described as Orthodox expressionism. The image displayed below is part of one of these poems (click on the image for full text and translation).

Laykhter (pseudonym of Meyer Voydislavski) was born in 1904 into a well-to-do Hasidic family in Lodz , Poland . He spent the years of the First World War in Russia , and it is likely that he encountered avant-garde poetics there. When he returned to Lodz after the war, he became active in the Orthodox political party Agudes Yisroel, helping to found its youth wing, then known as "Tseirey Emuney Yisroel" ("The Youth of the Faithful of Israel"). He also founded an Orthodox publishing house, Sgule, and an Orthodox Yiddish journal Ortodoksishe bletlekh (Orthodox Pages), that he edited himself and that appeared between 1922 and 1924. In 1925 he immigrated to Palestine where he continued to write both in Hebrew and in Yiddish for the Orthodox press both in Palestine and in Poland . He died in Tel Aviv in 1945 of a heart attack.

It is important to note that these activities were novel, even revolutionary, in the Orthodox sphere in Poland in the early years of the interwar period. Laykhter was involved in the formation of the institutions of organized Orthodoxy in Poland in a period in which new norms for a traditional way of life in the modern world were being set, and the parameters of an Orthodox lifestyle still very fluid. With his unique Orthodox expressionism, however, Laykhter pushed what was acceptable within Orthodox circles to the limit. At the root of expressionism, the dominant style in (secular) Yiddish poetry at the time, was Nietzsche's pronouncement that "God is dead" and the perception that the world was in a state of collapse. This stance is clearly antithetical to a religious world view, and yet Laykhter managed to convey the feeling of chaos and collapse that came to head in the First World War within a framework of faith.

The poem reproduced here, "Dos geshrey fun a stam in lerkayt fun velt" ("Someone's Cry in the Emptiness of World"), most clearly illustrates how Laykhter was able to use the expressionist aesthetic while at the same time asserting belief in God. The last few lines create a framework of faith, a simple faith in one God no matter what, that frees the poet to explore his relationship with a violent, fragmented world without the denial of God that the aesthetic implies. The poem does not, however, lend itself to a simple interpretation. Although the speaker clearly states his faith, the tension between the tormented bulk of the poem and its pious ending suggests that this faith has been shaken, and that it is only through an act of intellectual abstraction ("alef=one― / one God in the world") that the overwhelming sense of despair can be held in check.

Antologye fun religyeze lider un dertseylungen : shafungen fun shrayber, umgekumene in di yorn fun Yidishn hurbn in Eyrope / tsuzamengeshtelt fun Mosheh Prager. Nyu-York : Forshungs-Institut fun religyezn Yidntum, 1955. (Anthology of Jewish poems, stories and essays : written by religious authors, victims of Nazi persecution)

[1] Efraim Sicher, Style and Structure, 150. Shimon Markish notes that Babel also voiced an interest in translating Sholem-Aleykhem's 'Tevye the Dairyman' into Russian, though no such translation exists today. Shimon Markish, Babel i drugie (Moscow: Gesharin, 1997) 12.

[2] Gregory Freidin, 'Isaac Emmanuelovich Babel, a Chronology' in The Complete Works of Isaac Babel, ed. Nathalie Babel, Translated by Peter Constantine, with an introduction by Cynthia Ozick. New York, London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002, 1054.

Isaac Babel

Isaac Babel's dates span from 1894 to the ominous 1940, when he was killed while in imprisonment under the Stalin regime. He was a leading Russian Revolutionary fiction writer, and made no effort to suppress his Jewish background in his prose. As a child growing up in a middle class Odessa Jewish family, Babel would have heard Yiddish spoken, and spoke the language well enough himself to edit two volumes of Sholem-Aleykhem's stories in Russian, and to translate a Yiddish story, 'Dzhiro-Dzhiro,' by the fiction writer Dovid Bergelson.1 In his early years as a writer Babel experimented with topics of Jewish concern. His first story, 'Staryi Shloime,' written just after the Beiliss case in 1913, engages the Jewish encounter with anti-Semitism though the eyes of a tragic elderly Jew who kills himself when his children, faced with a Tsarist edict for the eviction of Jews from their homes, are baptized. His 1918 'Shabbos Nakhamu,' which was part of an unfinished cycle about a folk hero of Jewish lore, the wise trickster Hershele of Ostropol, shows that he is fascinated with the kinds of cultural prototypes appearing in the Yiddish literature of his time. After moving to St. Petersburg in 1916, Babel met the editor and writer who could make or break the career of young literateurs, Maksim Gorky, who published two of the young writer's stories in his journal Letopis, as well as hiring him as a correspondent for the newspaper Novaia zhizn' in 1918. Gorky was surrounded by his own aura and mythology – he was raised in poverty, had struggled for an education – his works were truly read en masse in Revolutionary Russia, particularly among Jews. (In fact, Sholem-Aleykhem and Gorky were good friends.) This connection to Gorky would help Babel to make a name for himself in 1923 when he began publishing his Red Cavalry stories in the avant-garde Lef and the fellow traveler journal Krasnaia Nov'.2

Silent Wigwams

'Silent Wigwams' is a long narrative Hebrew poem published in 1933 about American Indian life by Israel Efros, who was born in Ostrog, Poland in 1891, came to America in 1905, emigrated to Israel in 1954, where he died in 1981. The poem is set in the early eighteenth century around Chesapeake Bay and deals with the love affair between the daughter of an Indian tribal chief and an English artist who has been driven out of the white settler community. Efros's poem is one of several epic poetic compositions written by American Hebrew poets in the first half of the twentieth century. They belong to a larger cultural project of American Hebraism, which sought to establish an elite Hebraic culture among the leadership of American Jewry.

Writing about the Indians was the expression of a desire on the part of American Hebraists to contribute images and knowledge from the New World to the repertoire of the revival of world Hebrew literature. The figure of the American Indian embodied a primal connection to an American landscape unpolluted by urban culture, and the tragic fate of this group―the victimization of nobility and innocence―resonated with Hebrew writers as Jews and as members of a dying breed within American Jewry.

Silent Wigwams

'Silent Wigwams' is a long narrative Hebrew poem published in 1933 about American Indian life by Israel Efros, who was born in Ostrog, Poland in 1891, came to America in 1905, emigrated to Israel in 1954, where he died in 1981. The poem is set in the early eighteenth century around Chesapeake Bay and deals with the love affair between the daughter of an Indian tribal chief and an English artist who has been driven out of the white settler community. Efros's poem is one of several epic poetic compositions written by American Hebrew poets in the first half of the twentieth century. They belong to a larger cultural project of American Hebraism, which sought to establish an elite Hebraic culture among the leadership of American Jewry.

Writing about the Indians was the expression of a desire on the part of American Hebraists to contribute images and knowledge from the New World to the repertoire of the revival of world Hebrew literature. The figure of the American Indian embodied a primal connection to an American landscape unpolluted by urban culture, and the tragic fate of this group―the victimization of nobility and innocence―resonated with Hebrew writers as Jews and as members of a dying breed within American Jewry.

Dvora Baron

Dvora Baron (1887-1956) was the only woman fiction writer to have her work canonized in the literature of the Modern Hebrew Renaissance (1881-1920). Born into a rabbinic family in Ouzda, a small town outside of Minsk, Baron's first Hebrew stories were published in April 1902 when she was fifteen years old. After immigrating to Palestine in December 1910, Baron was appointed the literary editor of the important labor Zionist organ, ha-Poel ha-Tsair (The Young Laborer) newspaper, and married its founder and chief editor - Yosef Aharonovich. In 1923, Baron and Aharanovich both resigned from their positions at the newspaper, and Baron began a prolonged period of isolation in her apartment (thirty three years) until her death in 1956.

Baron's stories frequently deal with gender roles and class structure in traditional and newly modernizing Jewish communities both in Europe and in Palestine. Although she spent most of her literary career in Palestine, Baron did not ascribe to the Zionist 'imperative' of writing about life on the new Yishuv and 'negating,' in her stories, the experience of Jewish life in the Diaspora. Indeed, even Baron's stories set in Palestine tend to thematize the profound continuities that exist between traditional Jewish experience and modern Jewish experience, between life lived within a modern nationalist milieu and life lived according to the rhythms of religious faith and the struggle for daily survival.

[1] "Introspectivist Manifesto," trans. by Anita Norich in: American Yiddish poetry : a bilingual anthology / ed. Benjamin and Barbara Harshav. Berkeley : University of California Press, 1986. 774-784.

[2] Glatshteyn, 'A Short View of Yiddish Poetry,' tr. By Joseph Landis, Yiddish, Vol.1, no. 1 (Summer 1973): p.39. The essay originally appeared in the first two numbers of the In Zikh journal (1920).

Good Night, World

On or about April 1938, Yiddish culture changed. The journal In Zikh [In the Self] opened its April 1938 issue with a poem by Yankev Glatshteyn, one of its founding figures. Entitled "A gute nakht, velt" [Good Night, World], the poem quickly became a touchstone for Yiddish intellectuals in America faced with increasingly frightening news from Europe and seeking new ways in which to understand their own relationship to modernity. Glatshteyn (1896-1971) was one of the leading ideologues and poets of the inzikhist (introspectivist) movement which, in 1919, had proclaimed a new poetic day in Yiddish. "The world exists and we are a part of it," the first issue of the journal In Zikh announced. "But for us, the world exists only as it is mirrored in us, as it touches us." 1 There were no inappropriate subjects for poetry, as Glatshteyn declared, since Introspectivists 'do not know of any boundaries between themselves and the world, between feeling and thought. They recognize no taboo on the national or the social;' their subject was 'the wide world as it is reflected in the poet.' 2 'Good Night, World' asked whether the modern Jew could still count on the promises of the Enlightenment―that the Jews and even Yiddish could live in, be nourished by, produce world cultures, that they could live as citizens of their countries of residence, that "liberty, equality, and fraternity" applied to them too. The poem primarily reveals the tension of Yiddish writers like Glatshteyn, who felt themselves betrayed by the modern world yet were unable to reject it.

Else Lasker-Schueler

The portrait of the poetess Else Lasker-Schueler, made by Kaete Efraim Markus, tells a story within a story: tossed by fate and choice to the shores of the Mediterranean, Lasker-Shueler, who lived the latter years of her life in loneliness and misery in Jerusalem, is having her portrait made by a another Jewish German woman refugee, who found asylum in Palestine, but hardly her cultural home. The ambiguity of living in the Land of Israel, while feeling in exile, is portrayed in this picture by the mask Schueler wears, and by the image reflected in the mirror: nothing is as it seems, all images are just reflections of a bygone reality, conveyed by the elegant fur collar of Schueler's dress, so out of tune with Palestinian climate and the informality of dress and behavior of the emerging Jewish society there. The estrangement of exiles encapsulates Jewish fates in the 20th Century.

Satiric Utopist

Ephraim Kishon, who passed away earlier this year (2005) at the age of 81, was one of the most important Israeli satirists during the early decades of the state if not the most important one. Despite the wide popularity that he enjoyed as a writer, dramatist and film maker, his large body of work was never systematically studied, and has never been the focus of close academic attention.

While seemingly light and good humored, the satire of Kishon, in its diversity, in its activity as a cognitive and ideological tool uncovers a multitude of deep-seated problems which accumulate to form a critical mass ultimately threatening, even endangering the very existence of the satirist's society.

Kishon's utopia of an economically efficient, ultra-liberal bourgeois society – the utopia serving as the basis from which the satirical attacks were being planned and executed – was at odds with the socialist norms holding sway in Israel at the time of writing. But as history would have it, this utopia, or the ideology from which it stems, is now devoutly adhered to by the dominant powers in Israeli politics. Within Hebrew belle-lettres, Kishon's work – comic, ironic, versatile – can be considered as the blue-print of this ideology, the most eloquent, thorough and (certainly) the most entertaining we have.

Satiric Utopist

Ephraim Kishon, who passed away earlier this year (2005) at the age of 81, was one of the most important Israeli satirists during the early decades of the state if not the most important one. Despite the wide popularity that he enjoyed as a writer, dramatist and film maker, his large body of work was never systematically studied, and has never been the focus of close academic attention.

While seemingly light and good humored, the satire of Kishon, in its diversity, in its activity as a cognitive and ideological tool uncovers a multitude of deep-seated problems which accumulate to form a critical mass ultimately threatening, even endangering the very existence of the satirist's society.

Kishon's utopia of an economically efficient, ultra-liberal bourgeois society – the utopia serving as the basis from which the satirical attacks were being planned and executed – was at odds with the socialist norms holding sway in Israel at the time of writing. But as history would have it, this utopia, or the ideology from which it stems, is now devoutly adhered to by the dominant powers in Israeli politics. Within Hebrew belle-lettres, Kishon's work – comic, ironic, versatile – can be considered as the blue-print of this ideology, the most eloquent, thorough and (certainly) the most entertaining we have.

Satiric Utopist

Ephraim Kishon, who passed away earlier this year (2005) at the age of 81, was one of the most important Israeli satirists during the early decades of the state if not the most important one. Despite the wide popularity that he enjoyed as a writer, dramatist and film maker, his large body of work was never systematically studied, and has never been the focus of close academic attention.

While seemingly light and good humored, the satire of Kishon, in its diversity, in its activity as a cognitive and ideological tool uncovers a multitude of deep-seated problems which accumulate to form a critical mass ultimately threatening, even endangering the very existence of the satirist's society.

Kishon's utopia of an economically efficient, ultra-liberal bourgeois society – the utopia serving as the basis from which the satirical attacks were being planned and executed – was at odds with the socialist norms holding sway in Israel at the time of writing. But as history would have it, this utopia, or the ideology from which it stems, is now devoutly adhered to by the dominant powers in Israeli politics. Within Hebrew belle-lettres, Kishon's work – comic, ironic, versatile – can be considered as the blue-print of this ideology, the most eloquent, thorough and (certainly) the most entertaining we have.

Satiric Utopist

Ephraim Kishon, who passed away earlier this year (2005) at the age of 81, was one of the most important Israeli satirists during the early decades of the state if not the most important one. Despite the wide popularity that he enjoyed as a writer, dramatist and film maker, his large body of work was never systematically studied, and has never been the focus of close academic attention.

While seemingly light and good humored, the satire of Kishon, in its diversity, in its activity as a cognitive and ideological tool uncovers a multitude of deep-seated problems which accumulate to form a critical mass ultimately threatening, even endangering the very existence of the satirist's society.

Kishon's utopia of an economically efficient, ultra-liberal bourgeois society – the utopia serving as the basis from which the satirical attacks were being planned and executed – was at odds with the socialist norms holding sway in Israel at the time of writing. But as history would have it, this utopia, or the ideology from which it stems, is now devoutly adhered to by the dominant powers in Israeli politics. Within Hebrew belle-lettres, Kishon's work – comic, ironic, versatile – can be considered as the blue-print of this ideology, the most eloquent, thorough and (certainly) the most entertaining we have.

Satiric Utopist

Ephraim Kishon, who passed away earlier this year (2005) at the age of 81, was one of the most important Israeli satirists during the early decades of the state if not the most important one. Despite the wide popularity that he enjoyed as a writer, dramatist and film maker, his large body of work was never systematically studied, and has never been the focus of close academic attention.

While seemingly light and good humored, the satire of Kishon, in its diversity, in its activity as a cognitive and ideological tool uncovers a multitude of deep-seated problems which accumulate to form a critical mass ultimately threatening, even endangering the very existence of the satirist's society.

Kishon's utopia of an economically efficient, ultra-liberal bourgeois society – the utopia serving as the basis from which the satirical attacks were being planned and executed – was at odds with the socialist norms holding sway in Israel at the time of writing. But as history would have it, this utopia, or the ideology from which it stems, is now devoutly adhered to by the dominant powers in Israeli politics. Within Hebrew belle-lettres, Kishon's work – comic, ironic, versatile – can be considered as the blue-print of this ideology, the most eloquent, thorough and (certainly) the most entertaining we have.

Yehuda Amichai - Ludwig Pfeuffer (1924-2000) from Wuerzburg to Jerusalem

The Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai (1924-2000), recipient of the Israel Prize and a Nobel Prize candidate, is regarded as the unofficial 'national poet' of the State of Israel. His poetry has been translated into thirty-seven languages. Though he came of age with the State of Israel, Ludwig Pfeuffer, was born in the ancient city of Wuerzburg, Germany. His German-rooted Jewish Orthodox family emigrated to British Mandatory Palestine in the 1930s.

The role Pfeuffer's childhood in Germany played in the formation of his exclusively Hebrew literary corpus is an unstudied area in the field of Amichai scholarship. Amichai's concealment of the German sources of his poetry was so successful that only a concentrated scholarly effort may unearth them. However, the Hebrew Israeli verse cannot undo the Germanic foundations of the national Israeli poet's remarkable career.

All of Amichai's writing is suffused with materials drawn from the German world he left behind. These are the early sources that nurtured him in his formative years, the forces behind his work. The architectural and artistic faces of his birthplace; its music and songs; the textbooks in grade-school and the poems he had to memorize; the sounds of church-bells and the path he walked to school, all exist on the ocean-bed of his work.

Yehuda Amichai - Ludwig Pfeuffer (1924-2000) from Wuerzburg to Jerusalem

The Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai (1924-2000), recipient of the Israel Prize and a Nobel Prize candidate, is regarded as the unofficial 'national poet' of the State of Israel. His poetry has been translated into thirty-seven languages. Though he came of age with the State of Israel, Ludwig Pfeuffer, was born in the ancient city of Wuerzburg, Germany. His German-rooted Jewish Orthodox family emigrated to British Mandatory Palestine in the 1930s.

The role Pfeuffer's childhood in Germany played in the formation of his exclusively Hebrew literary corpus is an unstudied area in the field of Amichai scholarship. Amichai's concealment of the German sources of his poetry was so successful that only a concentrated scholarly effort may unearth them. However, the Hebrew Israeli verse cannot undo the Germanic foundations of the national Israeli poet's remarkable career.

All of Amichai's writing is suffused with materials drawn from the German world he left behind. These are the early sources that nurtured him in his formative years, the forces behind his work. The architectural and artistic faces of his birthplace; its music and songs; the textbooks in grade-school and the poems he had to memorize; the sounds of church-bells and the path he walked to school, all exist on the ocean-bed of his work.

Yehuda Amichai - Ludwig Pfeuffer (1924-2000) from Wuerzburg to Jerusalem

The Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai (1924-2000), recipient of the Israel Prize and a Nobel Prize candidate, is regarded as the unofficial 'national poet' of the State of Israel. His poetry has been translated into thirty-seven languages. Though he came of age with the State of Israel, Ludwig Pfeuffer, was born in the ancient city of Wuerzburg, Germany. His German-rooted Jewish Orthodox family emigrated to British Mandatory Palestine in the 1930s.

The role Pfeuffer's childhood in Germany played in the formation of his exclusively Hebrew literary corpus is an unstudied area in the field of Amichai scholarship. Amichai's concealment of the German sources of his poetry was so successful that only a concentrated scholarly effort may unearth them. However, the Hebrew Israeli verse cannot undo the Germanic foundations of the national Israeli poet's remarkable career.

All of Amichai's writing is suffused with materials drawn from the German world he left behind. These are the early sources that nurtured him in his formative years, the forces behind his work. The architectural and artistic faces of his birthplace; its music and songs; the textbooks in grade-school and the poems he had to memorize; the sounds of church-bells and the path he walked to school, all exist on the ocean-bed of his work.

Yehuda Amichai - Ludwig Pfeuffer (1924-2000) from Wuerzburg to Jerusalem

The Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai (1924-2000), recipient of the Israel Prize and a Nobel Prize candidate, is regarded as the unofficial 'national poet' of the State of Israel. His poetry has been translated into thirty-seven languages. Though he came of age with the State of Israel, Ludwig Pfeuffer, was born in the ancient city of Wuerzburg, Germany. His German-rooted Jewish Orthodox family emigrated to British Mandatory Palestine in the 1930s.

The role Pfeuffer's childhood in Germany played in the formation of his exclusively Hebrew literary corpus is an unstudied area in the field of Amichai scholarship. Amichai's concealment of the German sources of his poetry was so successful that only a concentrated scholarly effort may unearth them. However, the Hebrew Israeli verse cannot undo the Germanic foundations of the national Israeli poet's remarkable career.

All of Amichai's writing is suffused with materials drawn from the German world he left behind. These are the early sources that nurtured him in his formative years, the forces behind his work. The architectural and artistic faces of his birthplace; its music and songs; the textbooks in grade-school and the poems he had to memorize; the sounds of church-bells and the path he walked to school, all exist on the ocean-bed of his work.

Un-American Jewishness on the Hollywood Screen

With the advent of talking pictures in the late 1920s, Hollywood producers recruited New York playwrights to write for the movies. The great majority of producers and writers were Jewish, and the first talkie, 'The Jazz Singer,' famously tells of a cantor's son who chooses show business over the synagogue. But within a few years, overtly Jewish content and characters faded from the screen, as assimilationist movie moguls became anxious about anti-Semitism in America and abroad and were wary of jeopardizing the market appeal of their product. Thus when John Howard Lawson was hired to adapt his dark, anti-capitalist play 'Success Story' into a film (released as 'Success at Any Price' in 1934), producer Pandro Berman required him to strip it of its strong Jewish elements, and its two main characters, Sarah Glassman and Sol Ginsburg, became Sarah Griswold and Joe Martin.

'I always knew that my play would be cheapened in a film version,' Lawson recalled many years later, 'but the rejection of the Jewish theme meant the rejection of everything that gave it passion and life . . . [W]ithout it there would be nothing to distinguish it from other melodramas of sex and money.'

Lawson was born in New York City in 1894; his father, Simeon Levy, had Anglicized the family name. Lawson was, in his words, 'amazingly unconcerned about Jewishness' before entering Williams College in 1910, but was stung when prevented from joining the college newspaper because he was a Jew. For Lawson, Jewishness translated into radical politics. He was the leading communist in Hollywood in the 1930s, and the founding president of the Screen Writers Guild. In Lawson's World War II movie Sahara (1943), directed by Zoltan Korda and starring Humphrey Bogart, an American tank is lost in the Libyan desert. Biblical allusions abound as the crew searches for water, hoping for a miracle. No Jewish characters are portrayed in the film, but there are clear hints of 'ethnic substitution' in Lawson's screenplay. A black Sudanese Muslim and a Texan G.I. nicknamed 'Waco' eke water from an underground rock in a scene signifying interracial brotherhood. An Italian prisoner of war, refusing to conspire with a Nazi also held captive by the tank crew, denounces Hitler in a speech evocative of Shakespeare's Shylock:

'But are my eyes blind that I must fall to my knees to worship a maniac who has made of my country a concentration camp, who has made of my people slaves? Must I kiss the hand that beats me, lick the boot that kicks me, no! I rather spend my whole life living in this dirty hole than escape to fight again for things I do not believe against people I do not hate. As for your Hitler, it's because of a man like him that God – my God – created hell!'

As a member of the 'Hollywood Ten,' Lawson defied the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), accusing them of wanting to 'muzzle the great Voice of democracy . . . [and] attack Negroes, Jews, and other minorities.' He served nine months in Federal prison in 1950-51 for contempt of Congress. Blacklisted thereafter, he adapted 'Cry the Beloved Country,' also directed by Korda, for the screen, but novelist Alan Paton received sole credit. Lawson died in 1977.

Un-American Jewishness on the Hollywood Screen

With the advent of talking pictures in the late 1920s, Hollywood producers recruited New York playwrights to write for the movies. The great majority of producers and writers were Jewish, and the first talkie, 'The Jazz Singer,' famously tells of a cantor's son who chooses show business over the synagogue. But within a few years, overtly Jewish content and characters faded from the screen, as assimilationist movie moguls became anxious about anti-Semitism in America and abroad and were wary of jeopardizing the market appeal of their product. Thus when John Howard Lawson was hired to adapt his dark, anti-capitalist play 'Success Story' into a film (released as 'Success at Any Price' in 1934), producer Pandro Berman required him to strip it of its strong Jewish elements, and its two main characters, Sarah Glassman and Sol Ginsburg, became Sarah Griswold and Joe Martin.

'I always knew that my play would be cheapened in a film version,' Lawson recalled many years later, 'but the rejection of the Jewish theme meant the rejection of everything that gave it passion and life . . . [W]ithout it there would be nothing to distinguish it from other melodramas of sex and money.'

Lawson was born in New York City in 1894; his father, Simeon Levy, had Anglicized the family name. Lawson was, in his words, 'amazingly unconcerned about Jewishness' before entering Williams College in 1910, but was stung when prevented from joining the college newspaper because he was a Jew. For Lawson, Jewishness translated into radical politics. He was the leading communist in Hollywood in the 1930s, and the founding president of the Screen Writers Guild. In Lawson's World War II movie Sahara (1943), directed by Zoltan Korda and starring Humphrey Bogart, an American tank is lost in the Libyan desert. Biblical allusions abound as the crew searches for water, hoping for a miracle. No Jewish characters are portrayed in the film, but there are clear hints of 'ethnic substitution' in Lawson's screenplay. A black Sudanese Muslim and a Texan G.I. nicknamed 'Waco' eke water from an underground rock in a scene signifying interracial brotherhood. An Italian prisoner of war, refusing to conspire with a Nazi also held captive by the tank crew, denounces Hitler in a speech evocative of Shakespeare's Shylock:

'But are my eyes blind that I must fall to my knees to worship a maniac who has made of my country a concentration camp, who has made of my people slaves? Must I kiss the hand that beats me, lick the boot that kicks me, no! I rather spend my whole life living in this dirty hole than escape to fight again for things I do not believe against people I do not hate. As for your Hitler, it's because of a man like him that God – my God – created hell!'

As a member of the 'Hollywood Ten,' Lawson defied the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), accusing them of wanting to 'muzzle the great Voice of democracy . . . [and] attack Negroes, Jews, and other minorities.' He served nine months in Federal prison in 1950-51 for contempt of Congress. Blacklisted thereafter, he adapted 'Cry the Beloved Country,' also directed by Korda, for the screen, but novelist Alan Paton received sole credit. Lawson died in 1977.

Un-American Jewishness on the Hollywood Screen

With the advent of talking pictures in the late 1920s, Hollywood producers recruited New York playwrights to write for the movies. The great majority of producers and writers were Jewish, and the first talkie, 'The Jazz Singer,' famously tells of a cantor's son who chooses show business over the synagogue. But within a few years, overtly Jewish content and characters faded from the screen, as assimilationist movie moguls became anxious about anti-Semitism in America and abroad and were wary of jeopardizing the market appeal of their product. Thus when John Howard Lawson was hired to adapt his dark, anti-capitalist play 'Success Story' into a film (released as 'Success at Any Price' in 1934), producer Pandro Berman required him to strip it of its strong Jewish elements, and its two main characters, Sarah Glassman and Sol Ginsburg, became Sarah Griswold and Joe Martin.

'I always knew that my play would be cheapened in a film version,' Lawson recalled many years later, 'but the rejection of the Jewish theme meant the rejection of everything that gave it passion and life . . . [W]ithout it there would be nothing to distinguish it from other melodramas of sex and money.'

Lawson was born in New York City in 1894; his father, Simeon Levy, had Anglicized the family name. Lawson was, in his words, 'amazingly unconcerned about Jewishness' before entering Williams College in 1910, but was stung when prevented from joining the college newspaper because he was a Jew. For Lawson, Jewishness translated into radical politics. He was the leading communist in Hollywood in the 1930s, and the founding president of the Screen Writers Guild. In Lawson's World War II movie Sahara (1943), directed by Zoltan Korda and starring Humphrey Bogart, an American tank is lost in the Libyan desert. Biblical allusions abound as the crew searches for water, hoping for a miracle. No Jewish characters are portrayed in the film, but there are clear hints of 'ethnic substitution' in Lawson's screenplay. A black Sudanese Muslim and a Texan G.I. nicknamed 'Waco' eke water from an underground rock in a scene signifying interracial brotherhood. An Italian prisoner of war, refusing to conspire with a Nazi also held captive by the tank crew, denounces Hitler in a speech evocative of Shakespeare's Shylock:

'But are my eyes blind that I must fall to my knees to worship a maniac who has made of my country a concentration camp, who has made of my people slaves? Must I kiss the hand that beats me, lick the boot that kicks me, no! I rather spend my whole life living in this dirty hole than escape to fight again for things I do not believe against people I do not hate. As for your Hitler, it's because of a man like him that God – my God – created hell!'

As a member of the 'Hollywood Ten,' Lawson defied the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), accusing them of wanting to 'muzzle the great Voice of democracy . . . [and] attack Negroes, Jews, and other minorities.' He served nine months in Federal prison in 1950-51 for contempt of Congress. Blacklisted thereafter, he adapted 'Cry the Beloved Country,' also directed by Korda, for the screen, but novelist Alan Paton received sole credit. Lawson died in 1977.

Un-American Jewishness on the Hollywood Screen

With the advent of talking pictures in the late 1920s, Hollywood producers recruited New York playwrights to write for the movies. The great majority of producers and writers were Jewish, and the first talkie, 'The Jazz Singer,' famously tells of a cantor's son who chooses show business over the synagogue. But within a few years, overtly Jewish content and characters faded from the screen, as assimilationist movie moguls became anxious about anti-Semitism in America and abroad and were wary of jeopardizing the market appeal of their product. Thus when John Howard Lawson was hired to adapt his dark, anti-capitalist play 'Success Story' into a film (released as 'Success at Any Price' in 1934), producer Pandro Berman required him to strip it of its strong Jewish elements, and its two main characters, Sarah Glassman and Sol Ginsburg, became Sarah Griswold and Joe Martin.

'I always knew that my play would be cheapened in a film version,' Lawson recalled many years later, 'but the rejection of the Jewish theme meant the rejection of everything that gave it passion and life . . . [W]ithout it there would be nothing to distinguish it from other melodramas of sex and money.'

Lawson was born in New York City in 1894; his father, Simeon Levy, had Anglicized the family name. Lawson was, in his words, 'amazingly unconcerned about Jewishness' before entering Williams College in 1910, but was stung when prevented from joining the college newspaper because he was a Jew. For Lawson, Jewishness translated into radical politics. He was the leading communist in Hollywood in the 1930s, and the founding president of the Screen Writers Guild. In Lawson's World War II movie Sahara (1943), directed by Zoltan Korda and starring Humphrey Bogart, an American tank is lost in the Libyan desert. Biblical allusions abound as the crew searches for water, hoping for a miracle. No Jewish characters are portrayed in the film, but there are clear hints of 'ethnic substitution' in Lawson's screenplay. A black Sudanese Muslim and a Texan G.I. nicknamed 'Waco' eke water from an underground rock in a scene signifying interracial brotherhood. An Italian prisoner of war, refusing to conspire with a Nazi also held captive by the tank crew, denounces Hitler in a speech evocative of Shakespeare's Shylock:

'But are my eyes blind that I must fall to my knees to worship a maniac who has made of my country a concentration camp, who has made of my people slaves? Must I kiss the hand that beats me, lick the boot that kicks me, no! I rather spend my whole life living in this dirty hole than escape to fight again for things I do not believe against people I do not hate. As for your Hitler, it's because of a man like him that God – my God – created hell!'

As a member of the 'Hollywood Ten,' Lawson defied the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), accusing them of wanting to 'muzzle the great Voice of democracy . . . [and] attack Negroes, Jews, and other minorities.' He served nine months in Federal prison in 1950-51 for contempt of Congress. Blacklisted thereafter, he adapted 'Cry the Beloved Country,' also directed by Korda, for the screen, but novelist Alan Paton received sole credit. Lawson died in 1977.

Nefertiti's Granddaughter

The cover of Azzah, hafidat nifirtiti [Azzah, Nefertiti's Granddaughter], by Maurice Shammas (Abu Farid), published in Shefar 'Am, Israel, 2003. Born to a Karaite family in Cairo in 1930, Maurice Shammas was raised in harat al-yahud, the old Jewish quarter, and educated in Egyptian schools. Prior to his departure from Egypt in 1951, Shammas had worked as a journalist, and was involved in Egyptian theater. In Israel, Shammas has made a career working for the Arabic language section of the Israeli Radio and Television Broadcasting authority. He has also published three volumes of written work in Arabic, including the book depicted here as well a collection of short stories Al- shaykh shabtay wa-hikayat min harat al-yahud [ Sheik Shabbtai and Stories from Harat al-Yahud] (1979), and a slim volume of poetry Sab'a sanabil hazila[ Seven Lean Sheaves] (1989). Shammas's work stands out in the field of Egyptian Jewish nostalgia literature by providing a unique perspective on the richness of Arabic cultural integration in Egypt and by offering views of oft-forgotten spaces of the city, particularly harat al-yahud.

Contemporary Jewish Writing in Britain and Ireland

As Jewish writers are thought not to exist in Britain, the common reaction to this anthology of contemporary Jewish writings in Britain and Ireland has been, for the most part, one of incredulity. It is a literary canon that falls between two stools and thus is deemed not to exist. The English Literature academic establishment, on the one hand, has long since subsumed writers from most of the globe-- especially from America, Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, and Wales-- into the canon of "English" letters. Recent literary histories of modern English literature simply ignore British-Jewish writers or treat them as if they were not part of the culture as a whole. No wonder that British-Jewish writers have been either smothered at birth or, more usually, been simply left out in the cold. Judaic literary scholars, on the other hand, have tended to assume that the American-Jewish diaspora is synonymous with the Jewish diaspora tout court and that Anglo therefore equals American (to quote George Bernard Shaw: 'Americans and Britons are divided by a common language'). From the narrow perspective of exile and national rebirth, European writers are divided retrospectively into those who published before and after the Holocaust, with Britain occupying a strangely untouched space on the sidelines. Bemused students are often surprised to discover that authors such as Harold Pinter, Anita Brookner and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala can also be read Jewishly. Still, it is worth making a virtue of this marginality as British-Jewish writers have turned their very sense of marginality into lasting drama, poetry and fiction. The inbetweenness of modern British-Jewish writers has led to an extraordinary growth in the inventiveness and originality of this literature since the 1980s and this is beginning to be recognized generally.

Oppositional Culture and American Jewish Literature