Ytzig ha-Levi, a rabbi from Wetzlar in Hesse, converted to Christianity in 1546 after coming to read the Man of Sorrows in Isaiah 53 as a prophecy of Jesus Christ. He was baptized shortly after Luther's death in 1546, along with his young son Jacob, by the Lutheran theologian and biblical scholar Johannes Draconites (Drach). Christened Johannes Isaac Levita, he entered the University of Marburg. The Rabbi from Hesse became a Christian in an age of flourishing German Humanism, but also in the midst of a deepening confessional divide that was tearing apart Europe. When Hesse fell to the armies of Charles V in the Schmalkaldic War, Johannes Isaac was brought to the Netherlands to teach Hebrew at Louvain, and converted again, this time to Catholicism. In the early 1550s Johannes Isaac took up the chair of Hebrew at Cologne, where he would teach until his death in 1577. He entered a world hungry for Hebrew learning, but was also cast upon waves of religious warfare, especially when his gifted son Stephan (Jacob), abandoned Catholicism and converted a third time, to the Reformed Church.

Some forty years before, Cologne had been a mighty fortress of resistance against the study of Hebrew by Christians and its chief advocate, Johannes Reuchlin. Another Jewish convert, Johannes Pfefferkorn, had infamously tried to persuade the Emperor to round up and burn all Hebrew books in his realm. But Johannes Isaac was a different kind of convert. Rather than fiercely turning on his former coreligionists, as Pfefferkorn had done, Johannes Isaac worked tirelessly to persuade the world of Christian Humanists that the traditions of Hebrew and Jewish scholarship were important, even necessary, to the understanding of Sacred Scripture, of Christianity itself. Johannes Isaac's appointment to the chair of Hebrew at Cologne was a testimony to the victory of Catholic Biblical Humanism, as an ideal of learning and as a program of education.

Johannes Isaac would publish Hebrew grammars of his own as well as revised and expanded editions of grammars of others. He would also translate classics of Hebrew literature such as Maimonides' Letter on Astrology and the Sefer Ruah Hen into Latin, serving as a vital intermediary, bridging two different and distant worlds: the Jewish philosophy of Medieval Spain and Egypt, and the Republic of Letters of the Renaissance Humanists. In 1563-64, he was granted a year's leave of absence to help Christopher Plantin, a French printer established in Antwerp, to put to use the Hebrew types that he had been given on loan by the heirs of the Netherlandish printer in Venice, Daniel Bomberg. These were the very types with which such monuments of Jewish learning

Unlike crypto-Jews, who continued to secretly observe Judaism while living outwardly as Christians, Johannes Isaac's Christian faith, to all appearances, seems to have been real and sincere. If he remained loyal, it was not to the Law of Moses, but to the textual tradition of the Hebrew Bible in a wide and deep sense of the term. In sixteenth century Europe, Johannes Isaac, and like him a small set of deeply learned converted Jewish scholars such as Alfonso de Zamora in Castile, Felix Pratensis and Jacob ben Chaim ibn Adoniya in Venice and Paul Paradis in Paris, played an indispensable role, both in establishing Hebrew as part of the scholarly curriculum of European universities, and in editing editions of the Hebrew Bible printed by Christian printers for a Christian scholarly readership.

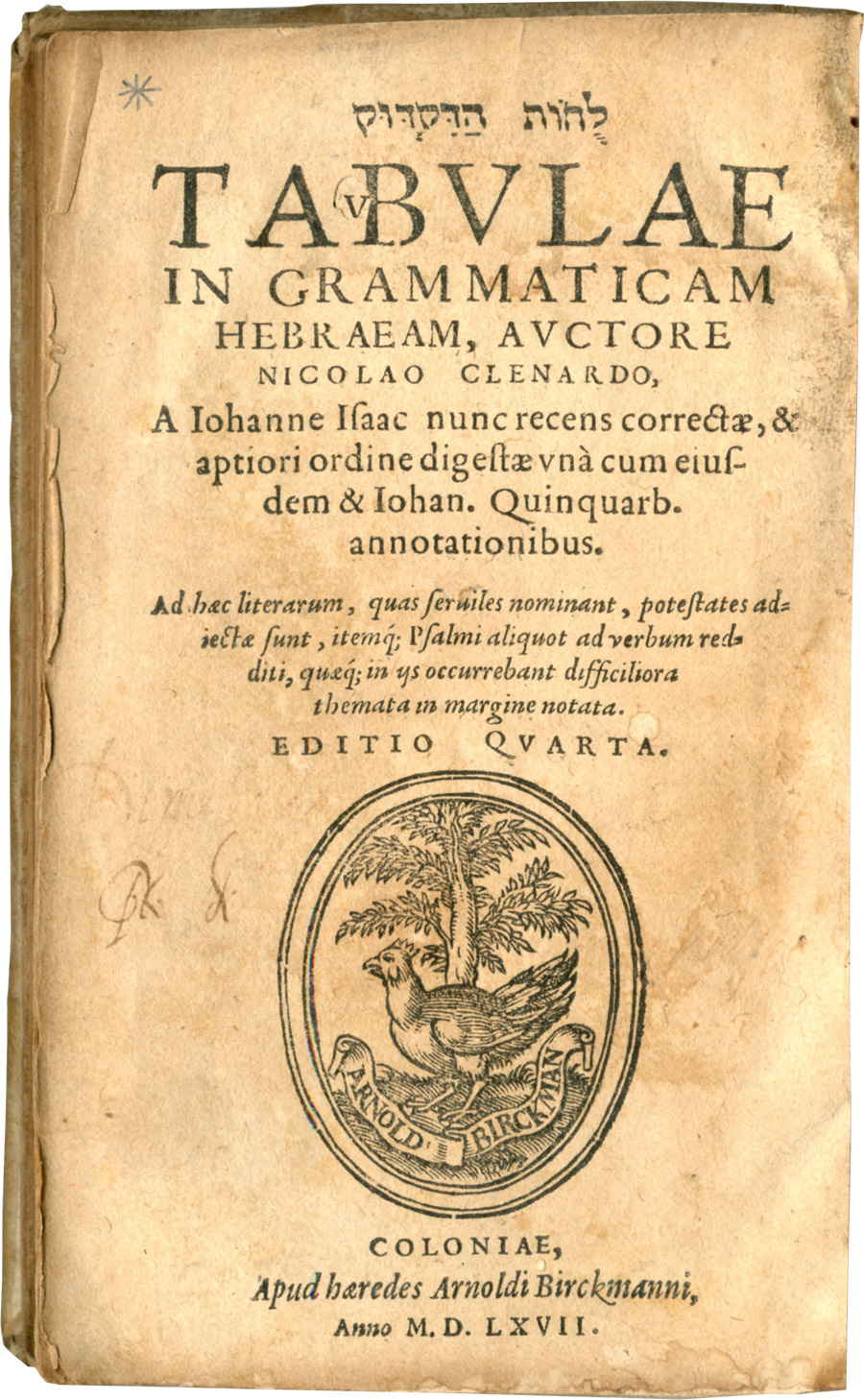

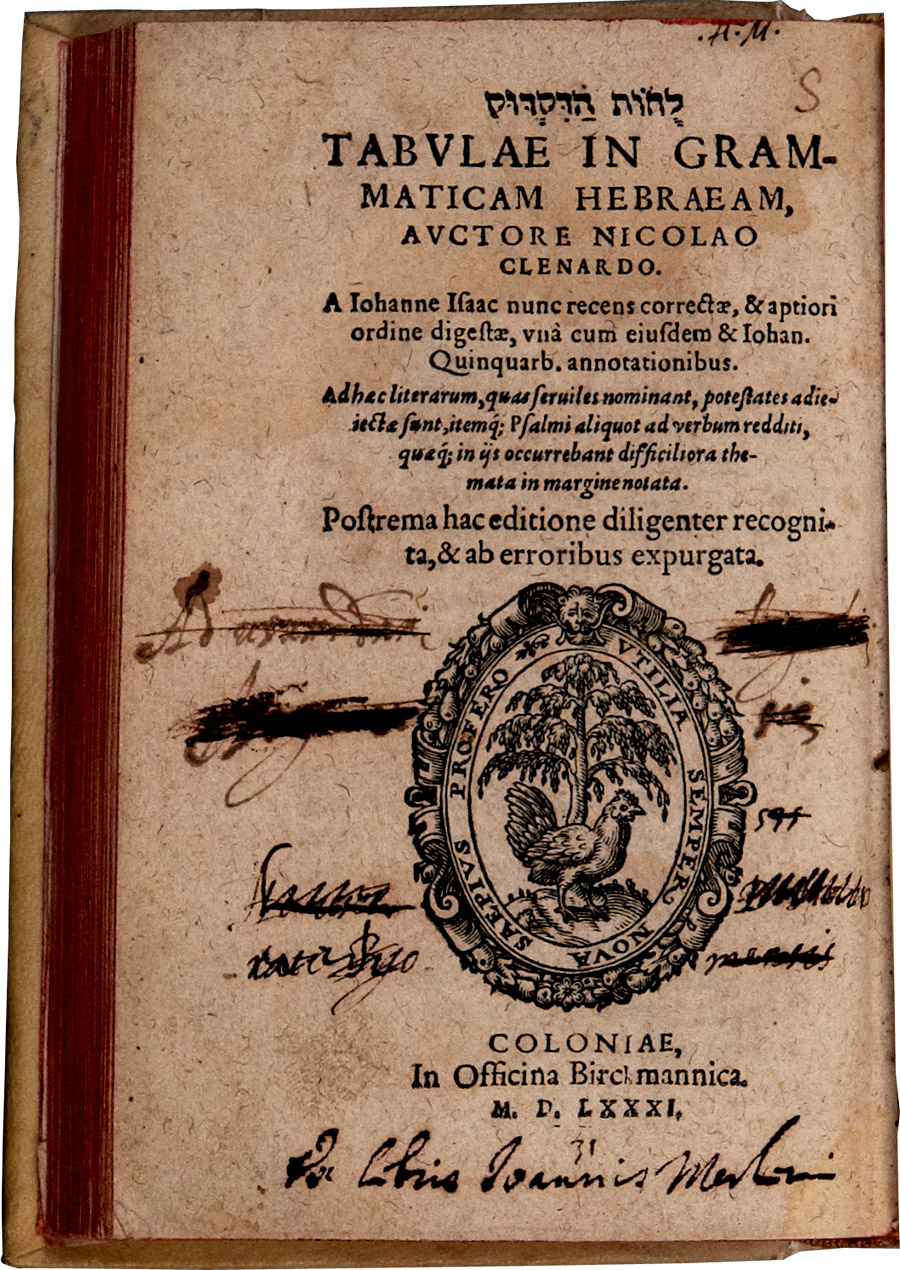

The Hebraica and Judaica Collections at the University of Pennsylvania preserve two copies of the Tabulae in Grammaticam Hebraeam, one of the most popular Hebrew grammars of the Early Modern period, composed by the path breaking Netherlandish scholar of Greek, Hebrew and Arabic, Nicolas Clenardus or Cleynaerts (1493-1542), in editions that were revised and expanded with commentary by Johannes Isaac. The oldest copy (Cologne, 1567) is at the Library at the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies. The second copy, in the Van Pelt Library Rare Book and Manuscript Library, once belonged to a Jean Merlin, possibly a relative of Jean-Raymond Merlin, the founding professor of Hebrew at the Calvinist Academy of Lausanne (though the latter died three years prior to this publication).