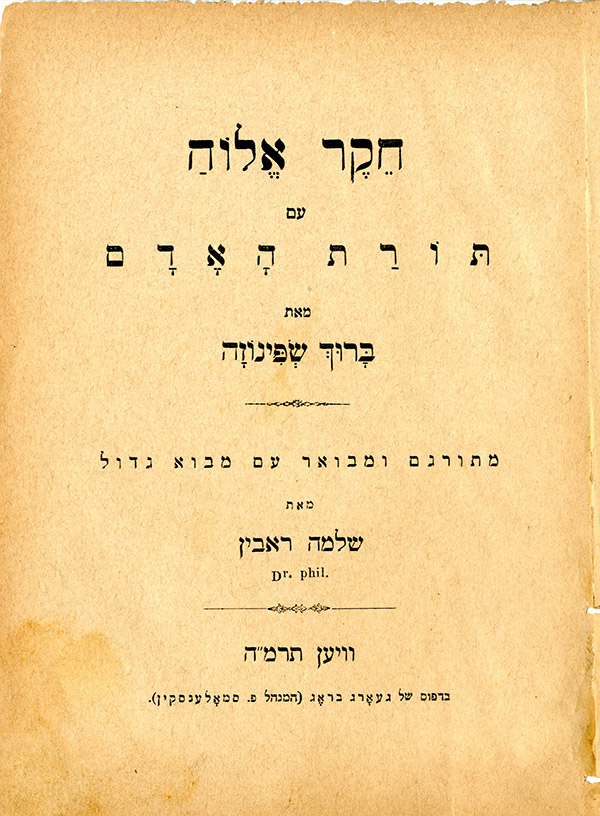

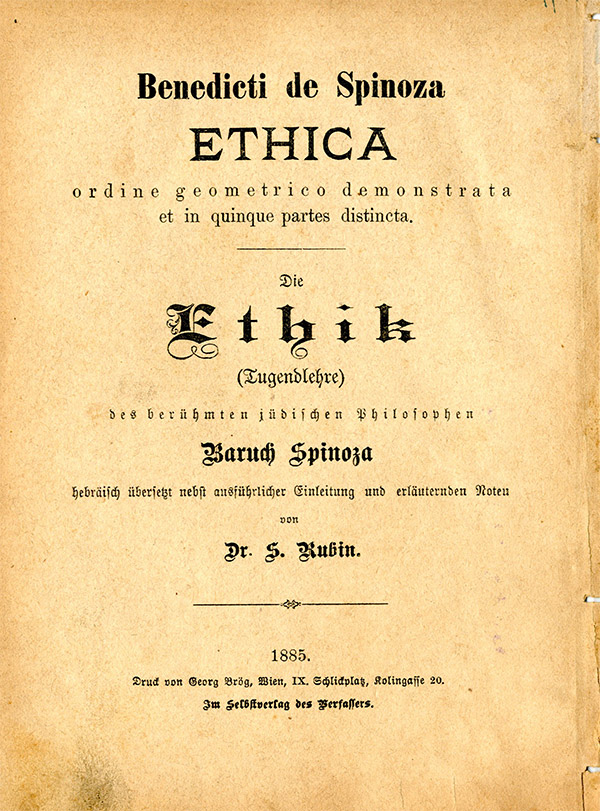

B. d. Spinoza, Heker ’Elohah ‘im torat ha-’adam [An Investigation of God with the Science of Man], translated by S. Rubin (Vienna: G. Brag, 1885).

The Dutch philosopher of Portuguese Jewish origin Baruch (or Benedictus) Spinoza (1632-1677) has undergone something of a renaissance in the last decades. The current revival is as striking for the variety of fields and genres represented as for its essentially similar bottom line: the idea of the rationalist thinker, pioneering biblical critic, and legendary conflater of God and Nature, as an originator of philosophical modernity, or perhaps we should say modernities, given the diverse and often contradictory intellectual legacies from the seventeenth century onward laid at his doorstep. One such legacy, Jonathan Israel has famously argued, was the so-called "Radical Enlightenment," which was distinguished from the moderate mainstream within the larger Enlightenment movement by its revolutionary esprit, its refusal to accommodate itself to religion, tradition, and the past, and its open commitment to the modern and secular as such. "Spinoza and Spinozism," Israel argues, were the " intellectual backbone of the European Radical Enlightenment everywhere, not only in the Netherlands, Germany, France, Italy, and Scandinavia but also Britain and Ireland."

And, we might add, in Jewish East Central Europe. Excommunicated by the Sephardic Jews of Amsterdam in 1656 for his "horrible heresies" and "monstrous deeds," Spinoza would remain a persona non grata in Judaism for nearly two centuries thereafter. Yet in the 1840s and 1850s, the Haskalah

By far, the most zealous champion of Spinoza in the campaign to reclaim him for Hebrew literature and culture was Salomon Rubin (1823-1910), a Hebraist maskil from Galicia. In 1856, Rubin wrote Moreh nevukhim he-hadash, or The New Guide to the Perplexed, his first of what would be many works over the next fifty years of his life dedicated to Spinoza. This was a two-volume apologia for an audacious venture

Nearly thirty years later, in 1885, Rubin finally came out with his long awaited translation of the Ethics. (He never finished translating the Theological-Political Treatise, which would have to wait until 1961 for a complete Hebrew rendering.) The Hebrew name he gave his translation, however, was not the literal Hebrew equivalent for the Ethics of Sefer ha-middot (as Jacob Klatzkin would later title his 1924 translation) but rather Heker ’Elohah ‘im torat ha-’adam, or An Investigation of God with the Science of Man. The change was significant. Rubin's Spinoza was no atheist. His system

Rubin's translation of the Ethics is today reduced to a footnote of Jewish history and Hebrew literature. Though it played an important role in introducing many fin-de-siC(cle Hebrew rebels to Spinoza