A group of Hebrew manuscripts produced between the 1550s and 1630s attests to the interest in astronomy of a small but significant circle of early modern Ashkenazi scholars spanning several generations. The manuscript evidence shows that they worked with a coherent corpus of texts which were copied and commented upon in a cumulative way. Some major figures such as R. Moses Isserles as well as some lesser known scholars such as Mattatiah Delacrut, Manoah Handel ben Shemariah, and Hayyim Lisker were part of this circle. The existence of these Hebrew manuscripts has been known to scholars, however, their content was usually dismissed as unoriginal. Upon closer inspection, and in the context of the general history of science, they tell a different story. MS UPenn LJS 498 from the Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection, a miscellany of astronomical texts, belongs to this family of manuscripts and speaks to these issues.

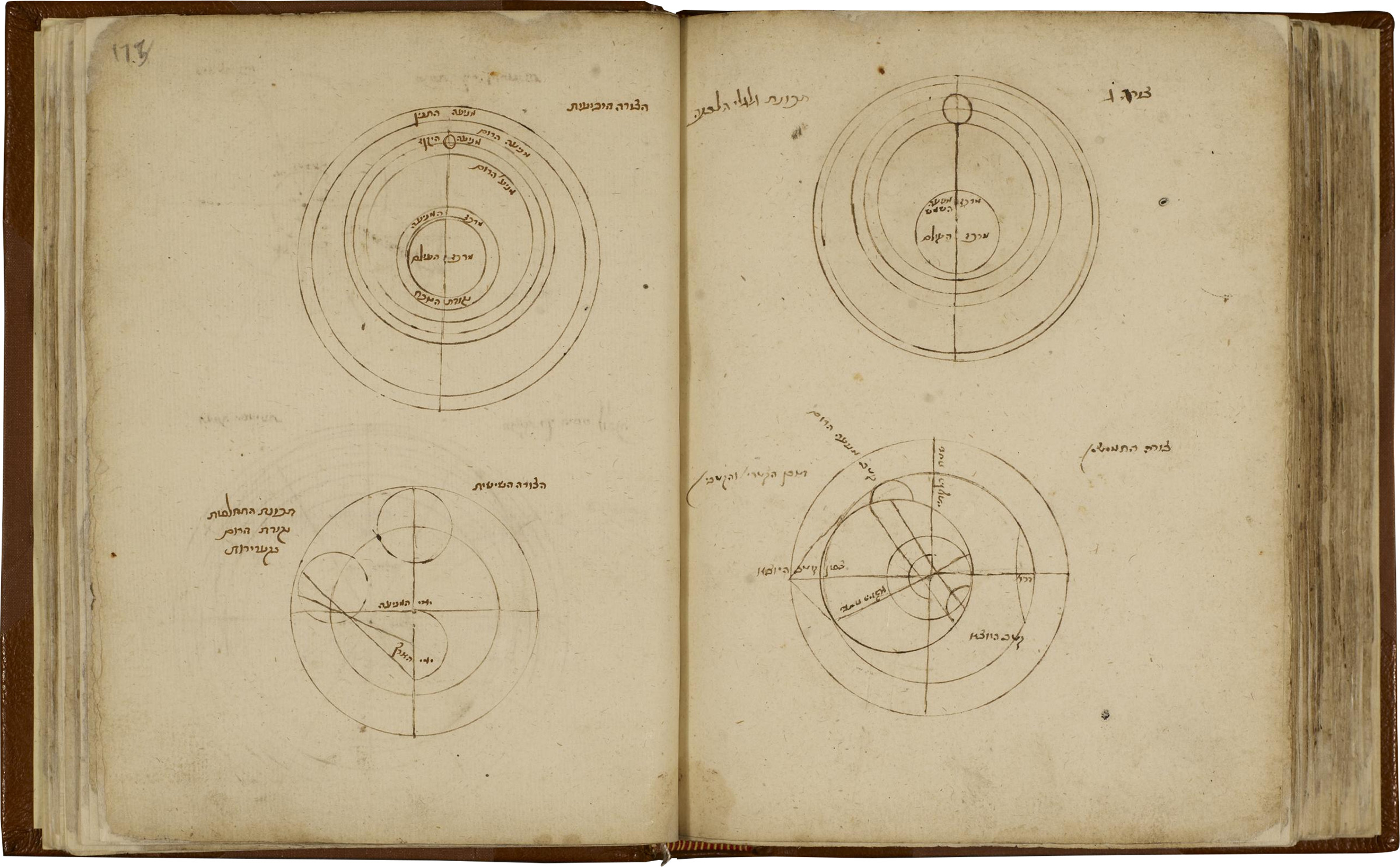

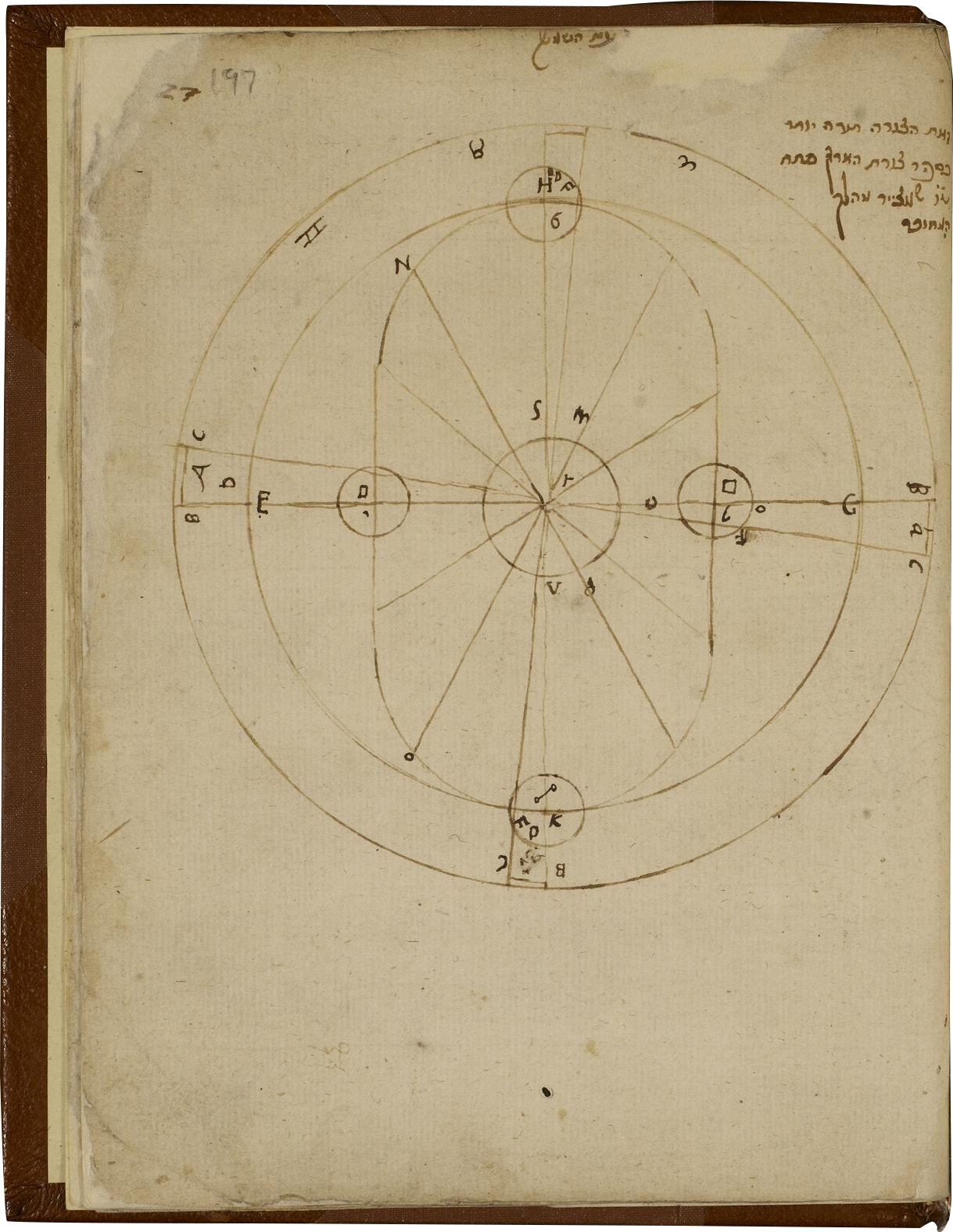

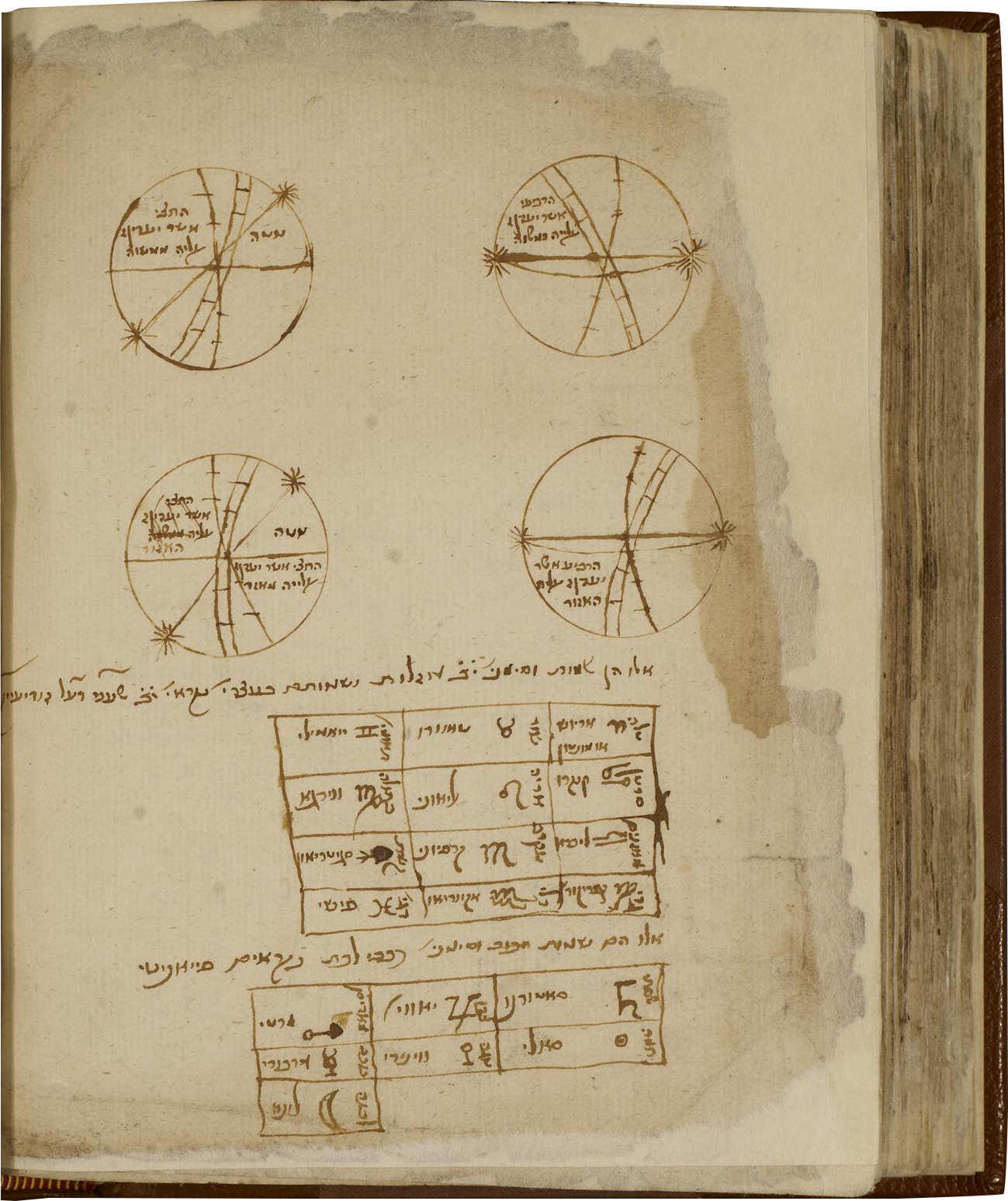

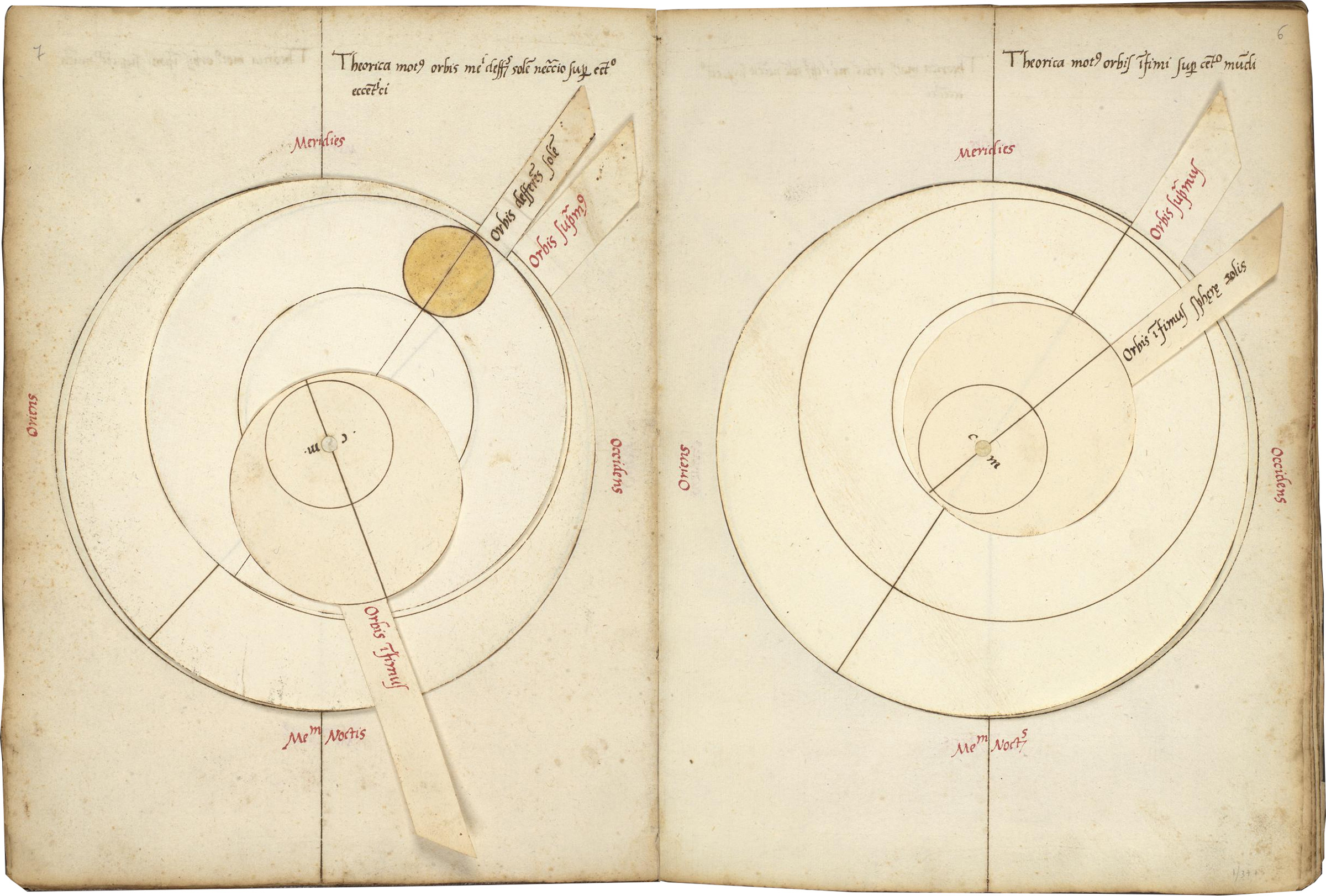

LJS 498 contains the medieval Sephardic scholar Abraham bar Hiyyaʼs Tsurat ha-arets and other astronomical and calendrical texts, including a treatise on the astrolabe. Bar Hiyyaʼs work, composed four hundred years earlier, was still deemed relevant by sixteenth-century scholars. The Hebraists Sebastian Münster and Erasmus Oswald Scheckenfuchs translated and published parts of it in Latin (Basle 1547). The presence of glosses of Manoah Handel ben Shemaria as well as the similarity of the diagrams connects MS UPenn LJS 498 with parts of another member of the group today found at Oxford University, MS Bodleian Library Opp. 696. A comparison of the two shows that the origin of some of the diagrams is in the Wittenberg edition of Peurbachʼs Theorica (1542). Opp. 696 features even the Latin captions, which are omitted in LJS 498. It is likely, then, that LJS 498 was copied from Opp. 969.

The generic features of this family of manuscripts, of which other members can be found in Oxford, Paris or Moscow, point to a shared interest in astronomy, calendrical issues and chronology, rather than to the exceptional interest of a few, unconnected individuals. The repeated presence of astrolabe charts accompanied by how-to manuals attests to their widespread interest in and involvement with astronomic observations. Their awareness of the 1542 edition of Peurbach is also important. Noel Swerdlow characterized Peurbachʼs Theoricae novae planetarum as “the principal textbook of planetary theory in Copernicusʼs time.” Moreover, the Wittenberg edition contained a commentary by Erasmus Reinhold, who was acquainted with Copernicusʼs heliocentric theory even before the publication of De Revolutionibus in 1543.

As material texts, the empty spaces in the manuscripts and otherwise unfinished drafts indicate occasional failed attempts to integrate the sophisticated diagrams into the text. The diagrams were deemed both essential and difficult to obtain. For these Ashkenazi Jewish students of astronomy, these drawings reflected an impulse to connect with their Christian counterparts. R. Moses Isserles promised the readers of his Hebrew commentary on Peurbach that “an intelligent man who already knows something of this discipline can study and understand his commentary in its entirety on his own, especially if he has at his disposal the diagrams found in the Latin/Christian Theorica,“ which he states is “widespread among them (i.e. the Christians)….” Special attachments containing astronomic diagrams and charts, sometimes with moving parts attached with thread, are then yet another common feature of our Hebrew manuscripts (present both in MS Opp. 696 and MS UPenn LJS 498), analogous to Christian book culture of the period, and attested by a Latin manuscript also found in the Schoenberg Collection, namely, MS UPenn LJS 64, which contains a beautifully designed set of illustrations to Peurbachʼs Theoricae.