In 1934, Leopold Stokowski's relationship with the board of the Philadelphia Orchestra had become strained over a decision by the board to mount operas as part of the orchestra's regular season. Stokowski was completely opposed to the idea. Arthur Judson, a supporter of the opera proposal, submitted his resignation in October 1934 (effective May 1935) after twenty-two years as manager of the orchestra. A few months later, in December 1934, Curtis Bok - a strong advocate of Stokowski's - resigned as president of the orchestra's board when members refused to approve his plans to reorganize the group.

It was then only a matter of time before Stokowski left. In response to Stokowski's prior threats not to renew his contract, the board had rallied to meet Stokowski's wishes, but in December 1935, when he once again said he could not agree to the terms of his contract renewal, the board accepted his decision, and the search for his successor was underway. The board quickly assembled a short list of conductors that met Stokowski's approval, and on 2 January 1936 Ormandy was named co-conductor with a three-year contract. At the time of the appointment, Ormandy still had one year left on his contract with Minneapolis, but the orchestra's management released him without challenge. Ormandy finished out the 1935-36 season in Minneapolis and returned for several guest appearances during the 1936-37 season.

Although the papers described Stokowski's decision not to renew his contract as "quitting" and "resigning," he had no intention to stop conducting the orchestra, and as Herbert Kupferberg writes in Those Fabulous Philadelphians, "the arrangement he made with the directors enabled him pretty much to have his orchestra and leave it, too." Just three months after the announcement, he led the orchestra on a thirty-one-day transcontinental tour of the United States, and during the first two years of Ormandy's appointment, he shared the podium with the new conductor. In 1938, Ormandy finally took over as music director of the orchestra, a position he held for forty-two years.

He had left Minneapolis almost as suddenly as he had come. No one had expected Ormandy, clearly a rising star, to remain in Minneapolis for the remainder of his career. During his five years at Minneapolis, he had returned regularly to the East Coast to conduct, and once a post became available with a major orchestra, he did not hesitate to take it.

Although Ormandy's tenure with the Minneapolis Symphony was the shortest of any of its chief conductors, over five years he was able to transform a talented regional orchestra into a highly disciplined ensemble that ranked among the best orchestras in the country. Ormandy brought the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra into the national spotlight, much as Leonard Slatkin would do for the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in the 1980s and Michael Tilson Thomas for the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra in the 1990s. Under these conductors, orchestras that had been second-tier ensembles gained a level of respect that rivaled that of the country's recognized major orchestras. By the time Ormandy left, the orchestra was one of four major orchestras heard regularly on the radio, and one of only two making recordings - the other being the orchestra that hired him, the Philadelphia Orchestra.

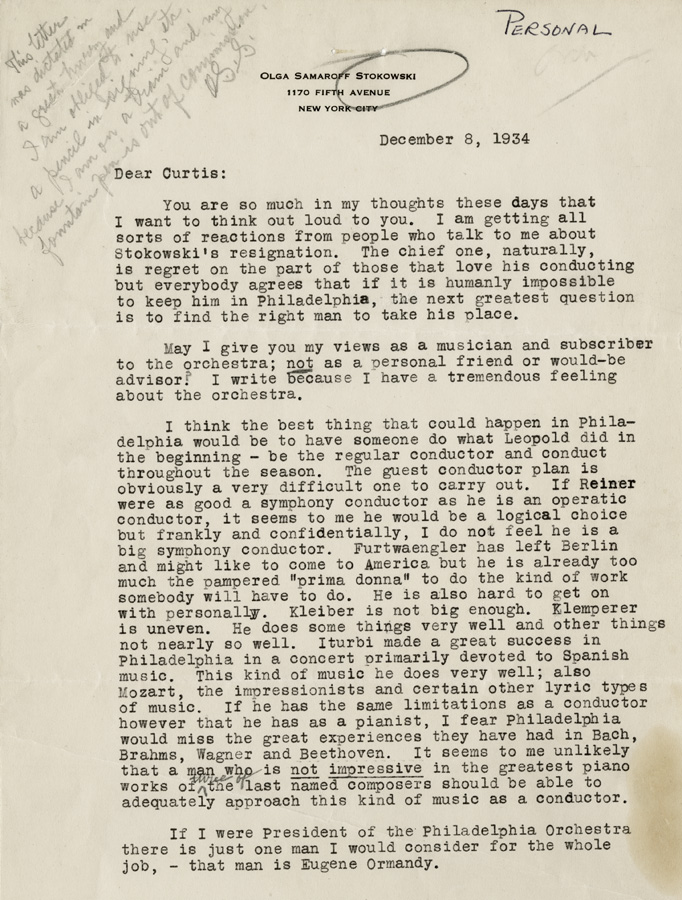

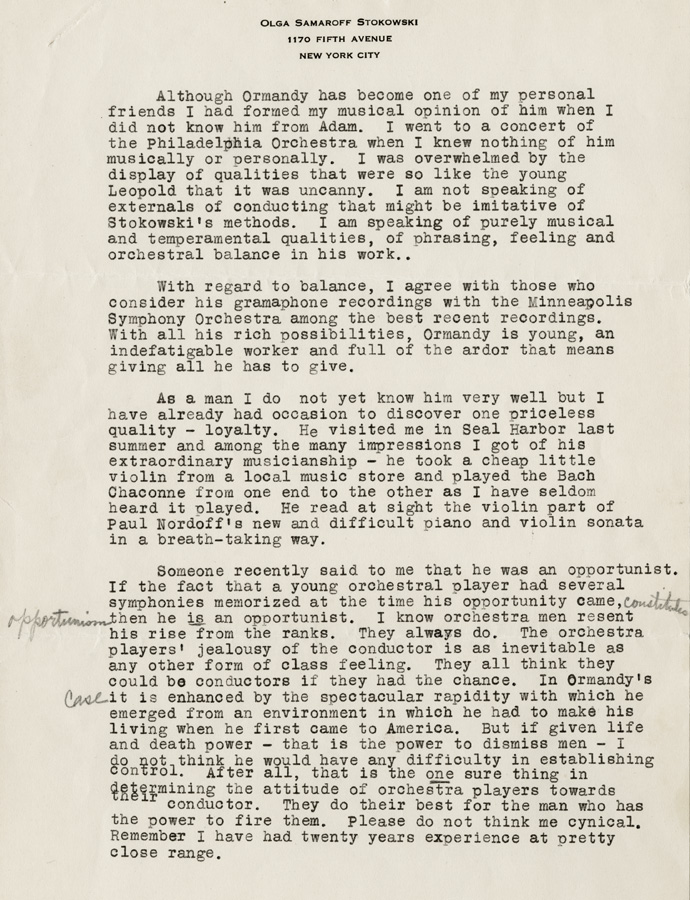

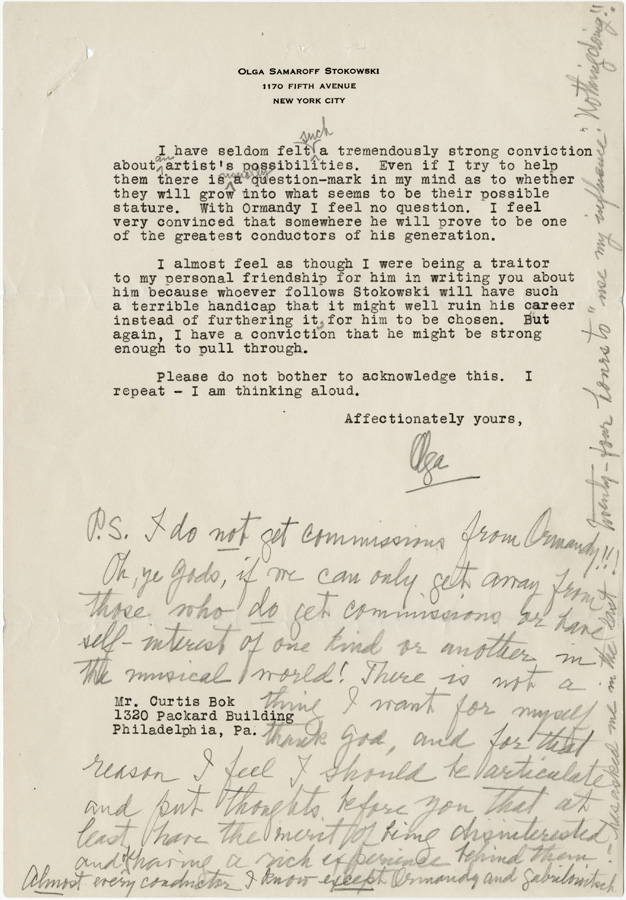

Fig. 1-3: Although Samaroff spent most of her time in New York City after her divorce from Stokowski in 1923, she remained involved in the Philadelphia music scene. When Stokowski threatened to leave the orchestra in 1934, she wrote this letter to Curtis Bok, president of the board of the Philadelphia Orchestra, to argue the case for Ormandy's appointment. A few days later, Bok would resign when the board refused to approve his reorganization plans.

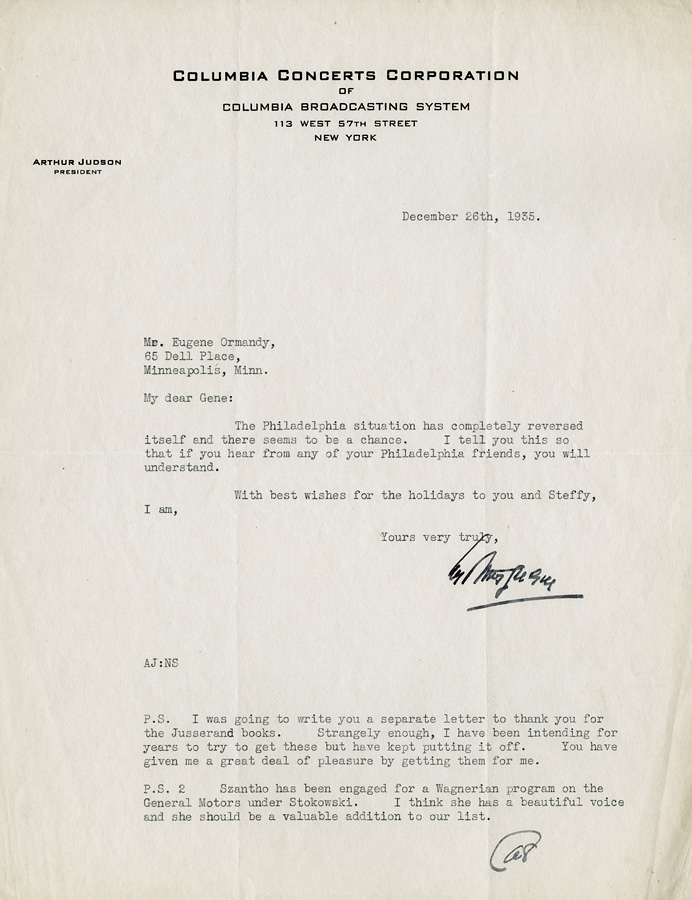

Fig. 4: Although Judson resigned as manager of the Philadelphia Orchestra effective May 1935, he remained a man of extraordinary influence in the world of classical music, and as Ormandy's personal manager, he negotiated Ormandy's contract with the orchestra. There was little reason for Ormandy to take the negotiations too seriously, since each time Stokowski had threatened to leave the orchestra in the past, the matter had been resolved. This letter from Judson was the first indication that the appointment might actually go through. Within a week, the contract had been signed, and the news was announced to the press.

Fig. 5: In official announcements, Stokowski cited "research" as the reason for not accepting a contract renewal, but he refused to discuss his plans in any detail. A few weeks after the announcement of Ormandy's appointment, a headline in the New York Times read "Stokowski Visions Rebirth of Classics. Says Science, through 'Plastic Modeling' of Sound, Will Add Beauty Even to Beethoven. Gives Aims of Research. Hopes to Bring out Untapped 'Profundities' of Music - Not through as Conductor." Stokowski's research was not mentioned again in the Times, however, and Stokowski continued to conduct.

Fig. 6: Stokowski's resignation fueled many rumors, including one that he was leaving Philadelphia to take over the New York Philharmonic as Toscanini's successor.

Fig. 7: Ormandy kept close ties with the Minneapolis Symphony during his first year in Philadelphia. He returned several times during the 1936-37 season, conducting four Friday concerts and one pop concert, and he brought the Philadelphia Orchestra to the Twin Cities during their spring tour. The rest of the season was filled by a succession of six guest conductors, including Dmitri Mitropoulos, who was appointed Ormandy's successor.