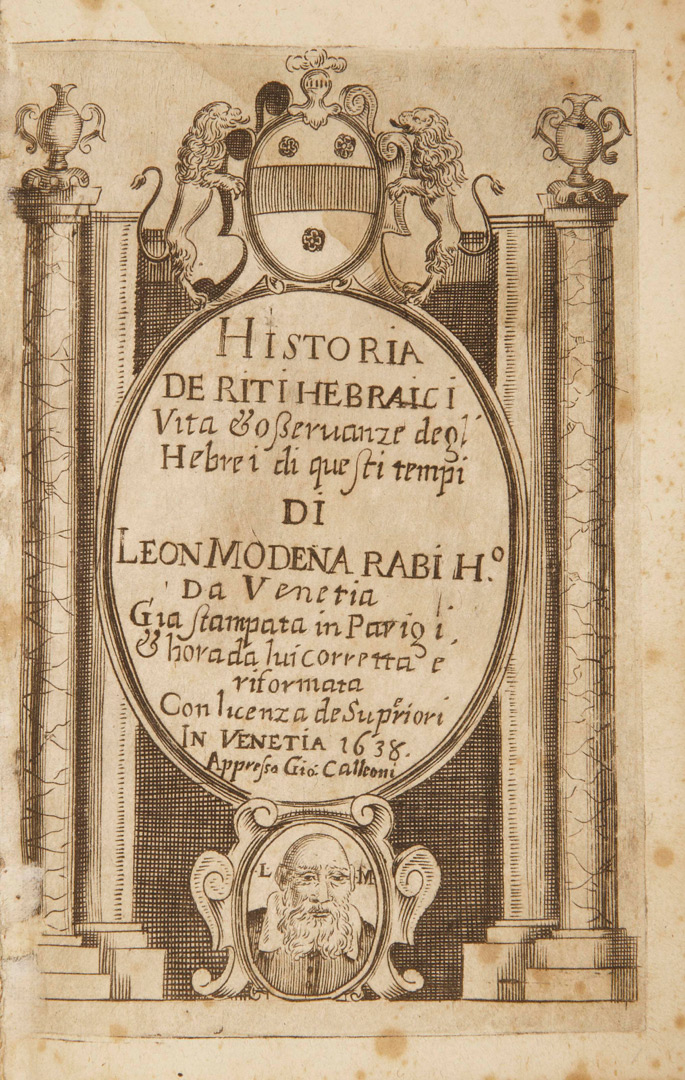

In both of its first editions (1637 and 1638), Historia de riti hebraici by the celebrated Venetian rabbi Leone Modena (1571-1648) is known for its exploration of Judaism as a rational and enlightened religious system and the Jews as civilized residents who deserved to at least be tolerated within Christian society. Yet, less known are its descriptions of Jewish daily life in contemporary Venice. Indeed, in Venice despite ghettoization many Jews felt at home. His portrait on the frontispiece of Historia de riti hebraici shows Modena bare-headed. Leone Modena was willing to adopt the Italian social habit to remove one’s hat before Christians of honor instead of following the Jewish custom of covering of the head. Yet this portrait tells us something also about the Jewish home in the ghetto: Venetian Jews commissioned their own portraits quite often and more than elsewhere in both the contemporary Sephardi and the Ashkenazi worlds. In affluent Venetian Jewish homes, the portego (the typical hall) was often decorated with still life paintings (nature morte), decorative wall hangings (arazzi), gilded leathers (cuori d’oro), and portraits.

The Jewish home in early modern Venice was as a space that opens onto an extensive social and cultural network of Jewish refugees of Sephardi origins, displaced after the medieval Jewish expulsions, along with Italian and Ashkenazi Jews as well as victims of slave-hunting corsair galleys that roamed throughout the Mediterranean. The latter could include Jews and Catholics, black sub-Saharan animists and Muslims, Christian Protestants and Orthodox, both men and women (mentions at 8-9, 37). Indeed, Historia de riti hebraici documents certain aspects of the reality of the ghetto in early-modern Venice and the cohabitation of Jewish families with Christian and Jewish servants and black slaves, who at the time were sold in the Barbary regencies (the centers of Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli), the independent kingdom of Morocco, and the east (the “Levant”) from Cairo to Constantinople (110).

Once transported to Venice, the preeminent occupation for black African slaves would have been domestic service. Manumission was a recurrent stage or an event in their life course and in the ghetto it happened through circumcision for men and immersion into the mikveh (ritual bath) for both men and women (110). Black Africans never constituted more than a very small minority of the slave populations of the cities of Italy. Rationales for their subjugation on the basis of skin color did not take hold as they did in Spain and Portugal. Slaves and servants also functioned as a symbol of status. Many Venetian Jews probably shared the view of a Leone Modena’s responsum that contemporary slaves were more like employees than possessions: “Nowadays, when our servants are held by us as comrades and not as slaves, as they were wont to term them in the past, we will not put them to harsh work. (Ziknei Yehudah, Venice 1650, no. 34).” Ultimately, Leone Modena’s Historia de riti hebraici as well as his and other contemporary Venetian rabbis’ responsa capture the complexity and alterity of the Jewish household and the broader Jewish society that in Venice were less prone to exclusivity, purification, and purgation than other early-modern religious and ethnic communities.