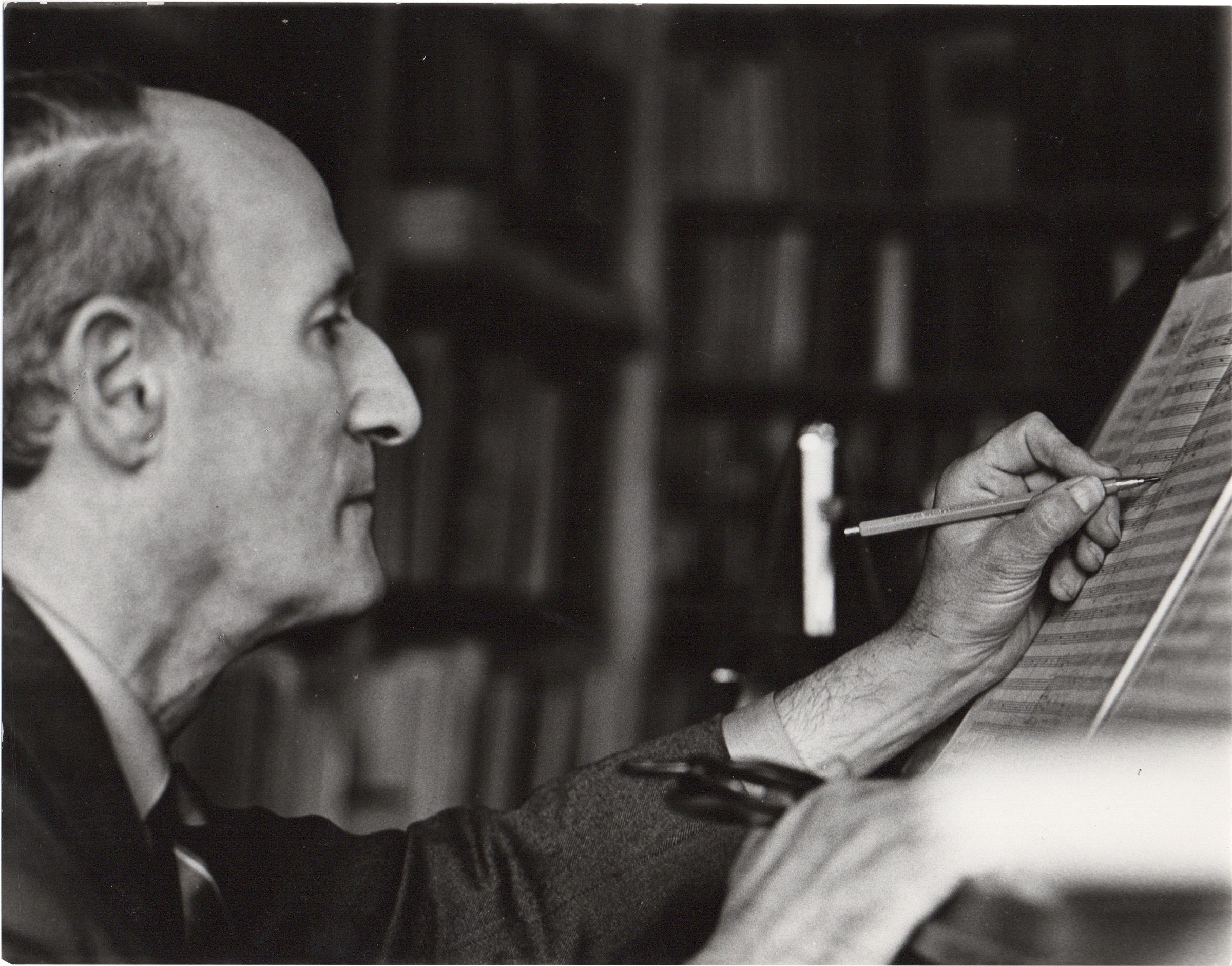

This photograph shows Ernst Hermann Meyer (1905-1988) composing at the piano in Berlin-Köpenick around 1970. All but forgotten today, Meyer was a key figure in the musical and cultural life of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). A composer, musicologist, and a university professor, he belonged to a small but prominent group of Jewish émigré intellectuals who moved to East Germany after 1945. This group included philosophers, composers, and authors such as Paul Dessau, Anna Seghers, Hans Mayer, and Ernst Bloch (both Mayer and Bloch later left for West Germany). Like other members of this group, Meyer’s decision to move to the GDR was motivated not only by the prospect of professional opportunities, but also

Meyer's family background was typical of the Berlin Jewish middle class with its strong trust in culture and learning. His father was a medical doctor who served in WWI and his mother was a painter who had studied with Max Liebermann. One of Meyer's most vivid childhood memories in connection with music was playing the violin with and for Albert Einstein who was a friend of his parents. Meyer studied composition with Paul Hindemith and completed his doctoral studies in musicology at the University of Berlin. During the 1930s, he came into contact with Hanns Eisler and his historical-materialist theory of music. Following Hitler’s seizure of power, Meyer used an opportunity to lecture in Cambridge in order to flee Nazi Germany. While in Great Britain, he continued to teach and compose and was active in various antifascist exile organizations. He moved to East Berlin in 1949 to take a position as Professor of Music Sociology at Humboldt University.

As a musicologist, Meyer was one of the pioneers of the social history of music. His direct models for this kind of research were the social histories of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. His study of early English Chapter Music is still valuable today. His positions on the aesthetic problems of contemporary music, however, are more likely to raise objections. In his writings and speeches, he propagated the official Soviet doctrine of Socialist Realism as the proper approach for contemporary musical production. Meyer himself followed this line in much of the music he composed from the 1950s on. A great part of his creative production in the GDR was dedicated to vocal compositions of a political nature, but he also composed film scores as well as large instrumental works such as the symphony Kontraste, Konflikte, a work containing moments of conflict and gloomy expression, apparently in contrast to the aesthetic imperatives of Socialist Realism. Some of Meyer’s musical compositions, such as his Mansfeld Oratorio, evoke the memory of the Jewish Holocaust but almost always from the viewpoint of the GDR's national myth of antifascist resistance with its emphasis on economic relations as the basis for WWII and the rise of National Socialism (thus, distorting, or at least downplaying, the ideological background of National Socialism in antisemitism).

Meyer died in October 1988, a year before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the final collapse of the Soviet Union. Being a committed communist for most of his adult life and a member of the Central Committee in the GDR, the way in which his life work is assessed today stands in direct relation to how the East German regime is viewed. Was he unaware of the extent of oppression in the GDR? Did he wholeheartedly believe in the system and its ideology? These questions must remain unanswered, but Meyer is one of many who, in their belief in the possibility of a perfect society, used the arts to promote a political utopia.