The abridgement as a separate literary genre came into its own in the age of printing, especially in sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when both readers and printers sought out condensed treatises to access original works in a more expedient way. For the consumer, digests facilitated the management of information, through the use of conceptual shortcuts, such as key concepts, representative passages and, at times, diagrams and visual aids. For the printer, the publication of abridgments, which were considerably shorter and physically smaller than the original work, offered the potential of wide circulation and economic profit.

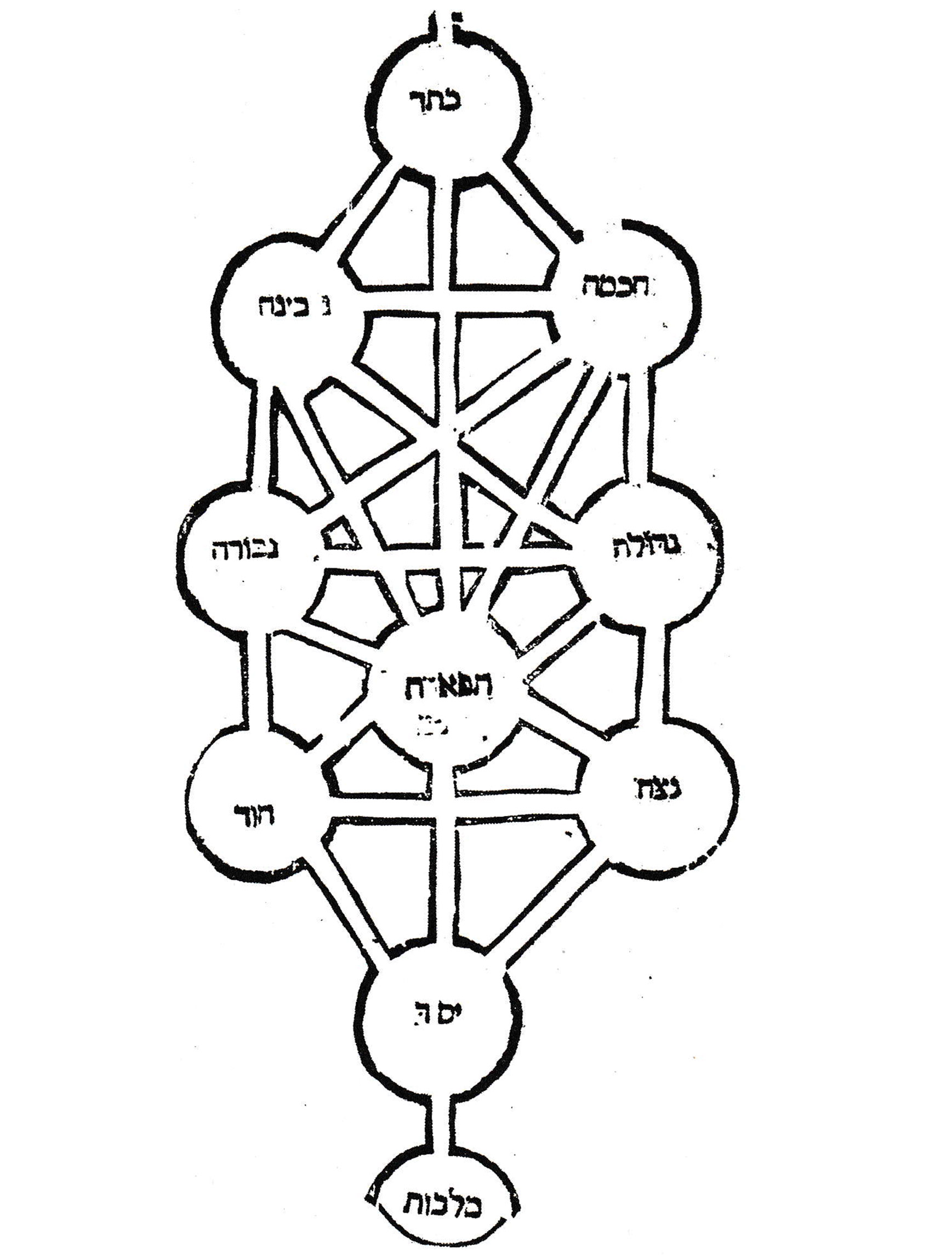

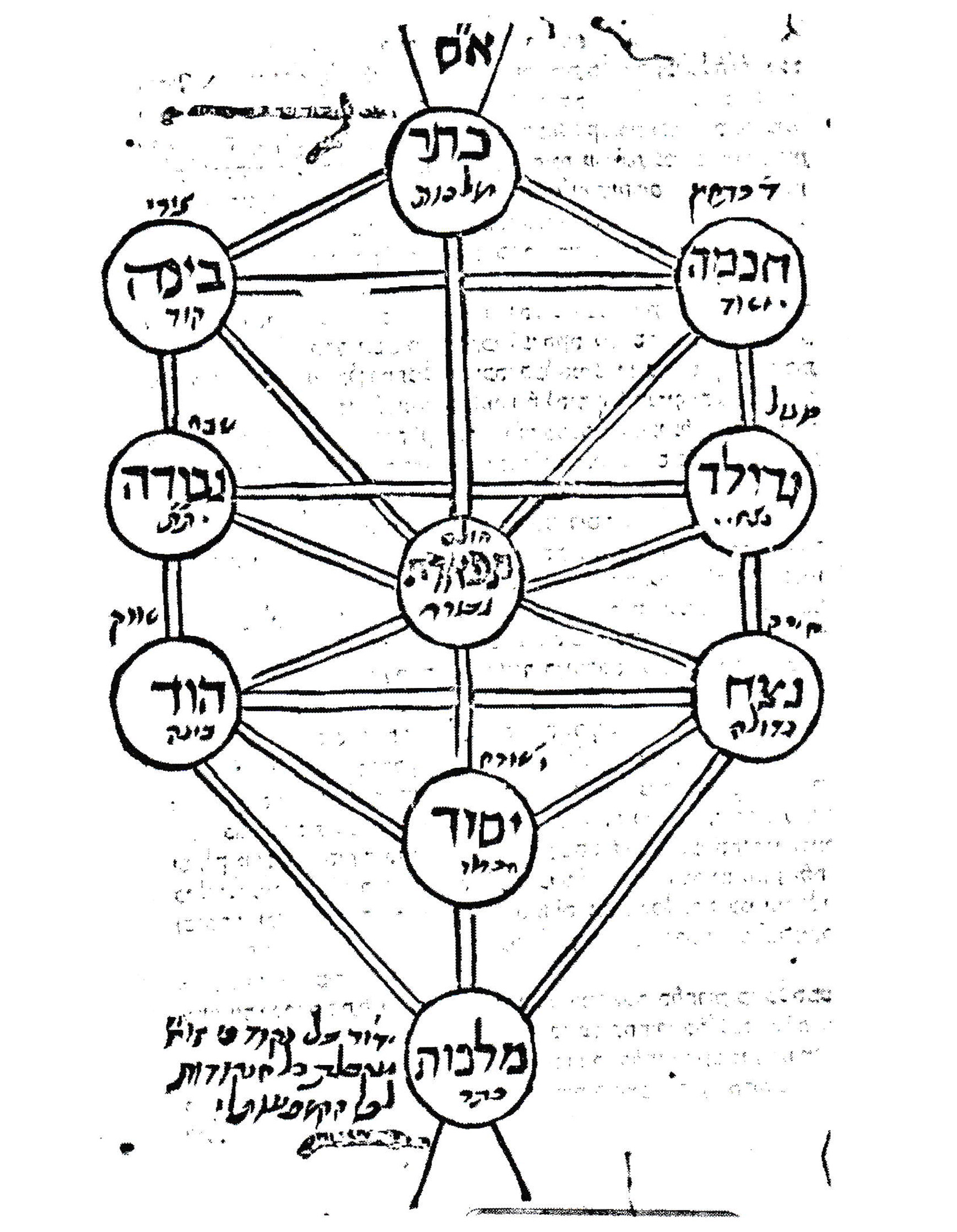

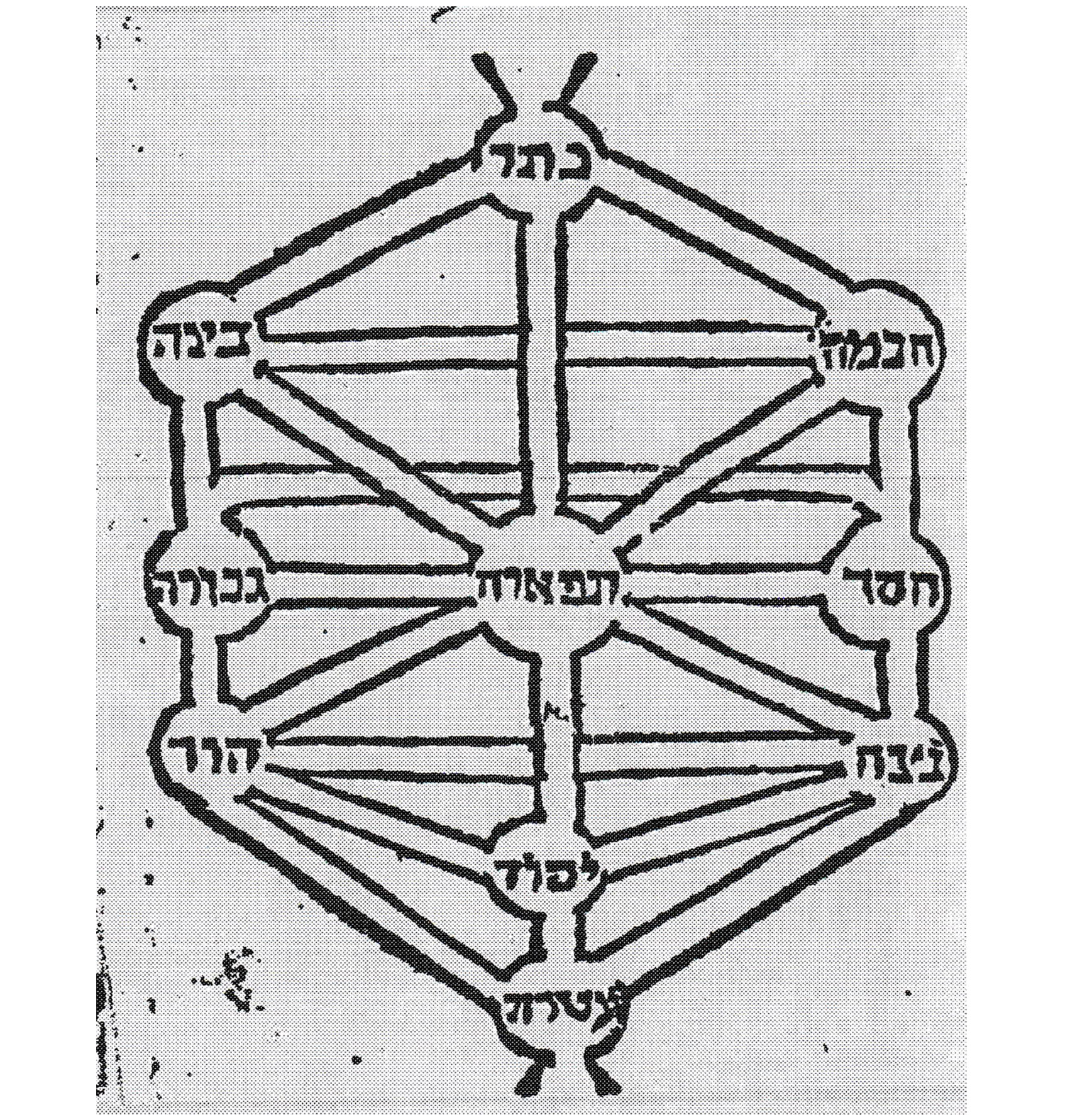

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, three kabbalistic abridgments to Moses Cordovero's Pardes Rimonim were printed within the same decade: Pelah HaRimon written by the famous Rabbi and Kabbalist Menachem Azariah da Fano (Venice, 1600); Assis Rimonim, edited using the work of R. Samuel Gallico with the marginal notes of R. Mordechai Dato (Venice, 1601); and Pithei Yah, written by R. Yissachar Baer ben Petahyah Moshe (Prague, 1609). An important technical feature of the original work, the Pardes Rimonim, was the author's inclusion of kabbalistic diagrams, interspersed throughout the text for the purpose of providing visual illustration of certain kabbalistic concepts and processes. Yissachar Baer's abridgment uses only one visual aid, a schematic diagram representing the ten Sefirot. What is interesting however, is that the 1591-92 Krakow/Nowy Dvor edition of the Pardes does not contain this diagram. Cordovero includes a similar sefirotic tree in Gate 7 of the Pardes, devoted to the explication of "channels," which function as conduits connecting the Sefirot and directing the divine emanation from one Sefirah to the next, nevertheless this diagram is markedly different from the one Yissachar Baer uses. Fano's Pelah ha-Rimon includes absolutely no kabbalistic diagrams, while Samuel Gallico's Assis Rimonim reproduces the highest number of visual illustrations from the Pardes. Fano's clear stance against incorporating visual images into a printed text is corroborated by his removal of these images when he undertakes to correct the Assis which gets finally reprinted devoid of any graphic representation in Mantua in 1623. The unique variance in the creative reproduction of texts and images in kabbalistic abridgments demonstrates the creative filtering of an abridger, who moves beyond mechanical reduction and creatively shapes the original work in ways consistent with his cultural, educational, and religious predispositions.