Book agents-subscription publishing in general-would eventually lose public confidence for a variety of reasons:

- a barrage of agents at the door proved annoying to many people;

- over time books sold by subscription came to seem of poor quality: their paper was cheap and their bindings shoddy; old works were endlessly reissued with new titles; information was out of date; authors were hacks;

- the price of subscription books often exceeded that of a good copy at a bookstore;

- gluts of books on timely topics competed with each other and over-saturated the market;

- publishers and agents misrepresented their works, using the names of eminent individuals on title pages and in related advertisements without authorization; faking testimonials; and titling works in ways designed to confuse the public.

Numerous condemnations of agents appeared in newspapers, magazines, and books. All reinforced the public's tendency to stereotype agents. Although these condemnations did not gain real force until the late nineteenth century, such critiques had already appeared in the first half of the century. Newspaper vignettes exhibited in this case, most dating from before the Civil War, show the prevalence of marketing techniques, codified in the advisory handbooks publishers printed and distributed to their agents, that many customers ultimately found objectionable.

In spite of the abuses, canvassers brought books to parts of the country where bookstores did not exist and where much of the population was barely literate. Some estimates assign canvassers responsibility for two-thirds of book sales from 1870-1900. That significant figure makes them important agents not only for the publishers whose products they hawked but also for the spread of literacy and print culture in America. Since the titles sold by subscription publishers were overwhelmingly written by American authors for American audiences focused on American topics, subscription publishing came to play an important role in the development of an American culture. The book agent may have been a mere travelling salesman, and not always a particularly savory specimen of the kind, at last. Nonetheless, just such agents helped define who we are and what we think through the books they placed on American shelves.

Fig. 1: As early as 1836 book agents were sufficiently common to generate this tale of a clergyman caught in a particularly persistent book agent's web. Early condemnation focuses more on the agents than on the publishers who sent them out into the field.

Fig. 2: Another Lowell newspaper article illustrates the determination of book "peddlers," another way of referring to book agents. Reprinted from the Louisiana Conservator, the story reveals the difficulty of extricating oneself from a book agent's grasp. Among the magical powers ascribed to the agent is the ability to "make you subscribe for a forthcoming work before you know it, even while you are determined to eschew the pedler and his works."

Fig. 3: This article on book agents admits that book agents are "a very respectable class of the business community, almost as important, we will venture to suppose, as books themselves." It then relates the monitory experiences of one gentleman who, pursued by them again and again, has come to dread their appearance. He even attempts to escape whenever he notices their approach.

Fig. 4: This letter, addressed to the Editors of the Free Press by a writer in Louisa County, Iowa, decries the multitude of canvassers. They sell

"So many things a person don't really need: -stencil plates, jewelry, liquid to plate your spoons yourself, medicines of different kinds, notions, books of every description, corsets, (ah me, I'll tell you in confidence dear Free Press, I bought one of those once, and found afterward, I had paid nearly double the retail price at the stores.)"

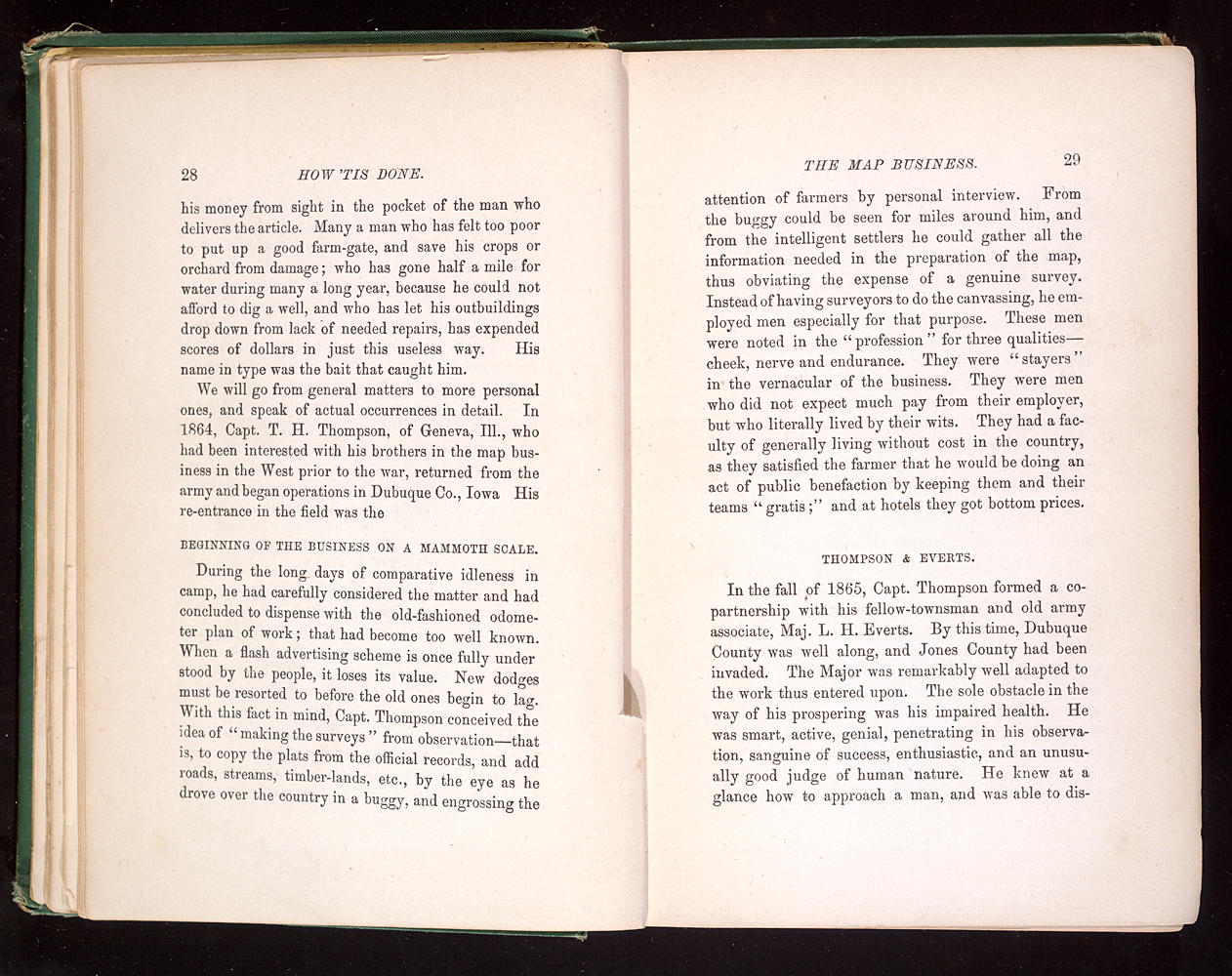

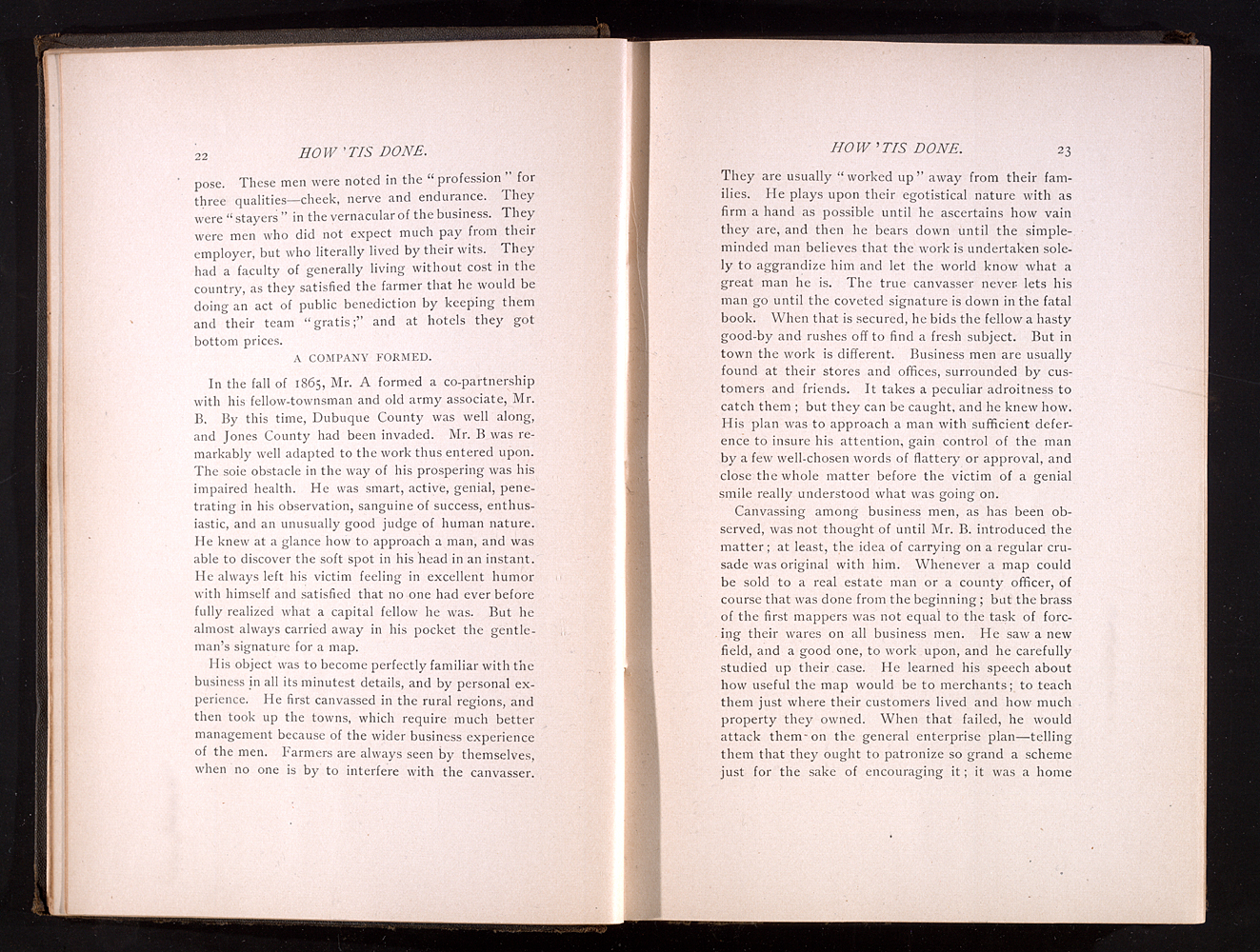

Fig. 5 and Fig. 6: One of the strongest condemnations of book agents and other canvassers is found in the 1879 edition of Bates Harrington's book on the subject. A detailed and scathing account of specific individuals and schemes, with names and locations delineated, Harrington reveals the "tricks of the trade. " He even reprints an entire general instruction manual, Success in Canvassing, directed specifically at book agents. By 1890, when the work was republished, the publisher-perhaps for protection against lawsuits-changed the names of individuals and businesses so that they could no longer be identified. The section titled "Thompson & Everts" has become in 1890 "A Company Formed." "Capt. T. H. Thompson" is, by 1890, "Mr. A;" his partner, "Maj. L. H. Everts," has become "Mr. B."

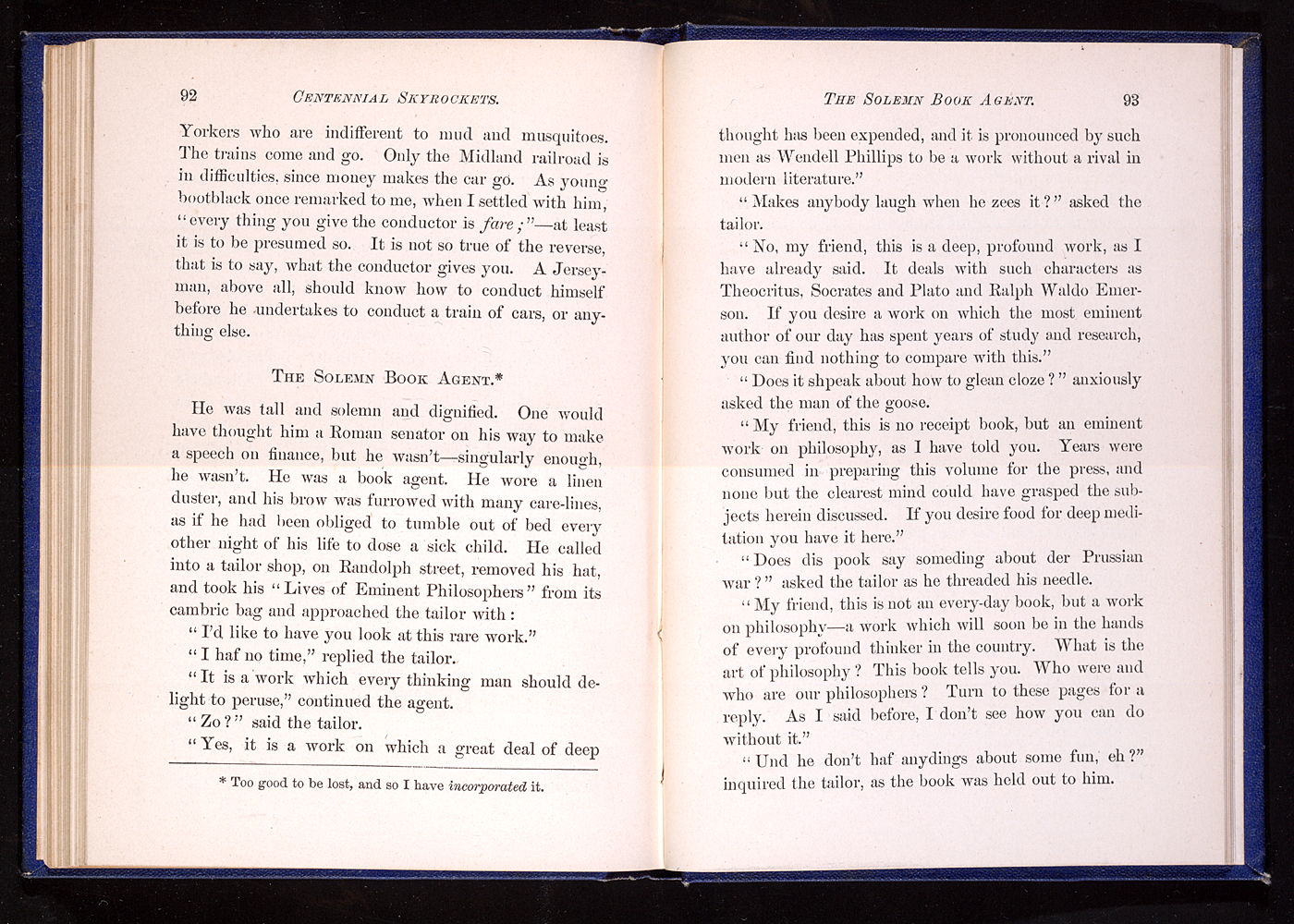

Fig. 7: Joslin's book is open to an anecdote that illustrates the difficulty book agents encountered in selling books to the general public. The unfortunate agent, canvassing a book of philosophy entitled Lives of Eminent Philosophers, unlikely to be of much interest to the general public, uses every technique he knows to impress the German tailor on whom he has called. However, once the tailor hears the price, he cries out:

"Zwelve dollars for der pook! Zwelve dollars und he has noddings about der war, und no fun in him, nor say noddings how to get glean cloze! What do you take me for, mister? Go right away mit dat pook, or I call der bolice und haf you locked up pooty quick."

Fig. 8: By 1898, subscription publishing had become a wellestablished part of the book trade and was no longer viewed, as in the early days, as an aberration, damaging to regular bookstores, and possibly even putting them out of business. The article chronicles abuses in the industry but also recognizes its merits in bringing the book to the "sparsely-inhabited districts of the Wild West."

Fig. 9: These pages from Reed's Encyclopedia are of some short discussions towards of back meant to justify the subscription publishing business against articles and books that condemn the practice. Publishers reacted in different ways to growing criticism of their industry. Some developed detailed and convincing spiels to respond to the common negative reactions encountered by canvassers. At first glance, these discussions seem intended for the agent. A careful reading indicates that potential subscribers were also meant to read these printed justifications.

Fig. 10:

Clark, a Congregational minister and founder of the Young People's Society of Christian Endeavor, was also a newspaper editor and the author of over three dozen titles. The letters collected here were originally written for the Golden Rule, a religious weekly that became the organ of his Christian Endeavor movement. The letters are all penned by a fictional Mr. Mossback, described in "An Introductory Note" as "an aged and garrulous old man, . . . a harmless old pastor." Among the letters are a number of extremely humorous criticisms on the various "types" the pastor has observed and encountered in his working life. Mr. Mossback commends "some unrecognized saints," among whom-- surprisingly?--he includes book agents. True, Mossback admits, the agent

"may deserve some of the opprobrium that is cast upon him, for his persistence in the sale of his wares is not always of the gentle and winning variety, but after all we are inclined to consider him one of the benefactors of humanity."