Today, we are most likely to first become aware of subscription publishing from statements on title pages alerting readers that the book they hold is for sale "by subscription only" or from the ubiquitous "agents wanted" notices in newspapers and periodicals of the period. Publishers who wished to sell books by subscription needed first to hire agents, or "salespeople," to canvass, or "sell," their works. To find agents, they used advertisements in local newspapers and national periodicals, and later in trade publications, direct mailings, handbills and broadsides, and word of mouth. Sometimes publishers even sought agents in the canvassing books themselves or in the complete works that subscribers purchased. Publishers wrote advertisements encouraging individuals to take the plunge using the same techniques of persuasion they would subsequently encourage their agents to employ in selling their works.

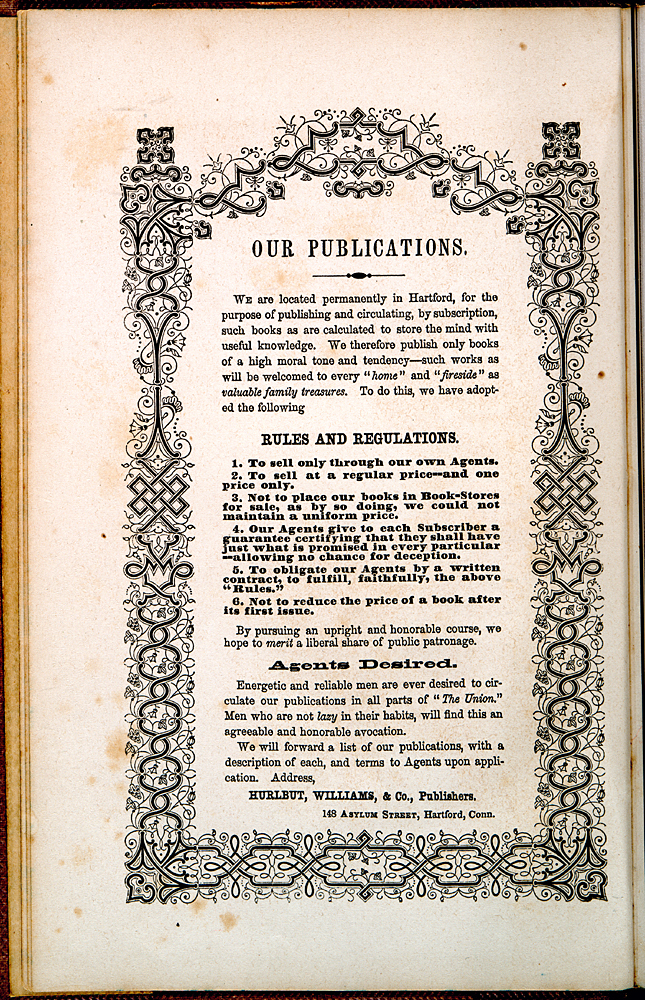

Fig. 1: This canvassing book seeks both subscribers and canvassers, as can be seen from this advertisement for agents. While such extensive advertisements are rare, the announcement "Agents Wanted" or "Agents Needed" often appears at the bottom of the title pages of both canvassing books and the actual subscription books themselves. The Connecticut publisher who, during the Civil War, reprinted this popular military memoir, first published in 1823, seeks "energetic and reliable men . . . to circulate our publications in all parts of 'The Union.'"

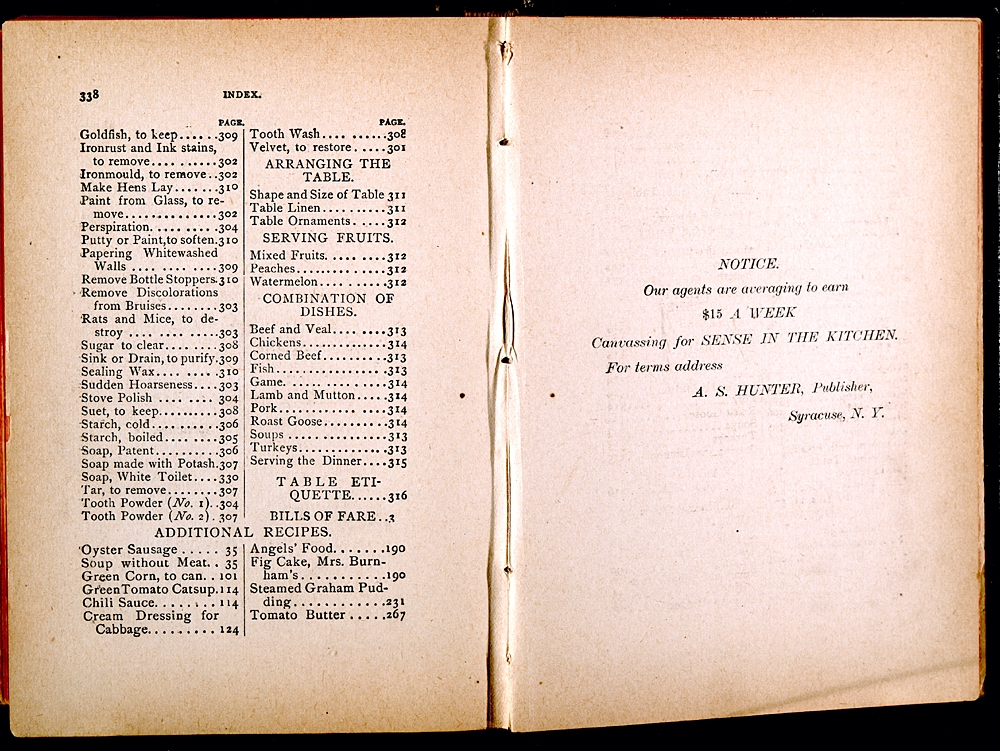

Fig. 2: Not a canvassing book but the work as sold to subscribers, Sense in the Kitchen includes an advertisement soliciting agents. The publishers sought their agents among the population who had actually purchased or otherwise seen a copy of Adam's work.

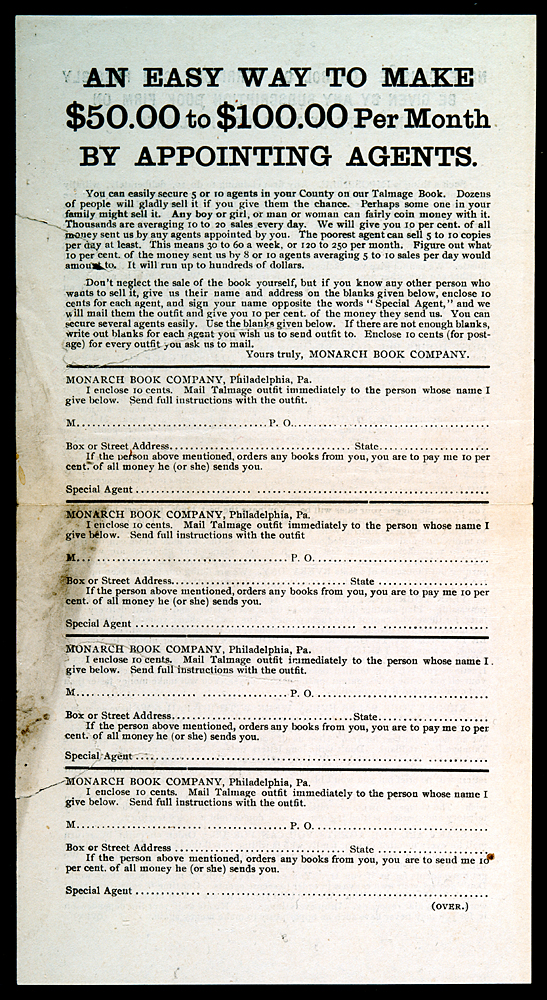

Fig. 3: Seeking agents to canvass their books, publishers employed a variety of techniques to locate prospects. These included direct payments or a percentage of profits to those who supplied them with names. These arrangements usually provided that no money would change hands until the prospect actually took up the profession for a designated amount of time or earned a certain amount of money. This advertisement seeks "Special Agents" to submit the names of other potential agents, promising riches to be gained through the aggregation of ten percent of each agent's proceeds. To encourage only serious prospects, the "Special Agent" is required to send ten cents to cover the postage for sending the outfit to each name submitted.

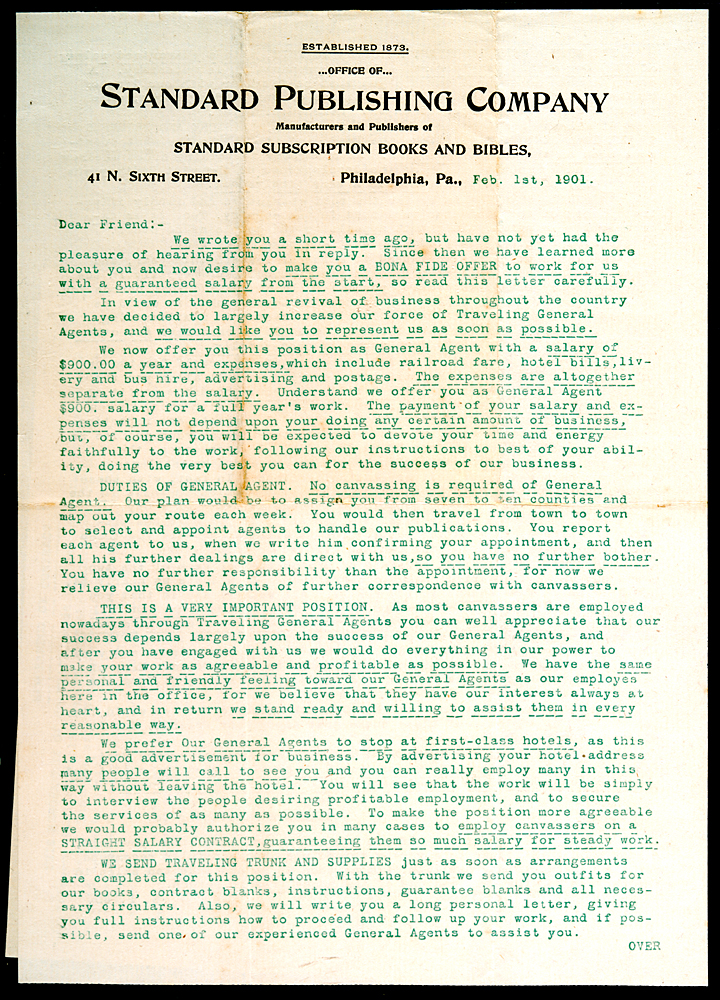

Fig. 4: Publishers also sought agents through direct solicitation. This letter seeks "Traveling General Agents" to "select and appoint agents to handle our publications." Unlike appointed agents, who canvassed for subscriptions and were paid only in commissions, Traveling General Agents received both salary and expenses. However, before "securing the General Agency," a candidate had to spend two to three weeks actually canvassing, achieve at least thirty-five to forty sales, and pay twenty-seven cents postage for the canvassing outfit. These requirements were obviously the publisher's way to separate the wheat from the chaff.

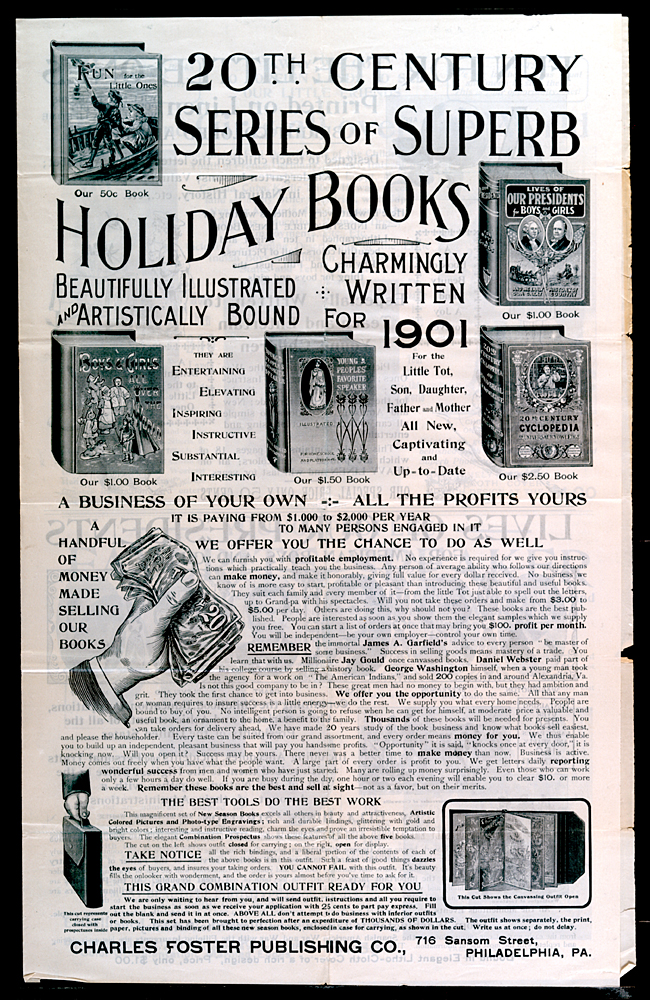

Fig. 5: Publishers considered the holiday season an ideal time to bring out new books, especially those that could be given as gifts to children and young people. It was also, by analogy, an ideal time to canvass, and to seek new canvassers. This recruiting poster encourages prospective canvassers by tying the two essential elements, books and money, together visually. "Any person of average ability who follows our directions can make money, and make it honorably, giving full value for every dollar received." Who could readily resist such rhetoric?

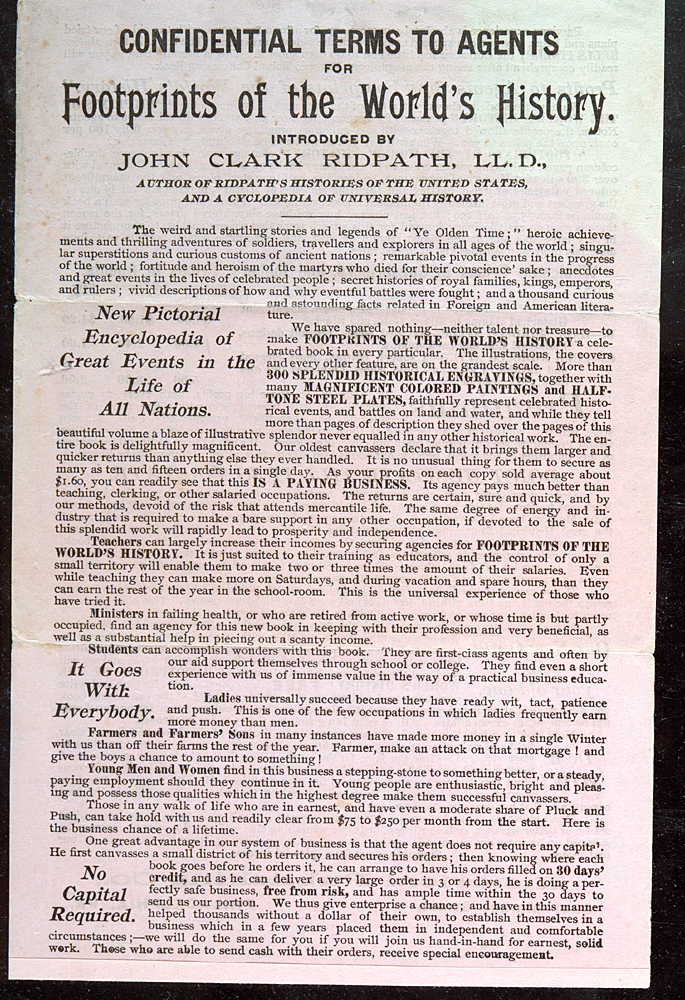

Fig. 6: This advertisement seeks particular kinds of people who, it explains, would make ideal agents for this publication. Teachers, ministers, students, ladies, and farmers are among those regarded as appropriate sales personnel. The publisher claims that they will be able to work during their spare time, support their education, pay down their mortgage, or use this job as a stepping stone to something better. All the prospect needs in order to succeed is "a moderate share of Pluck and Push."

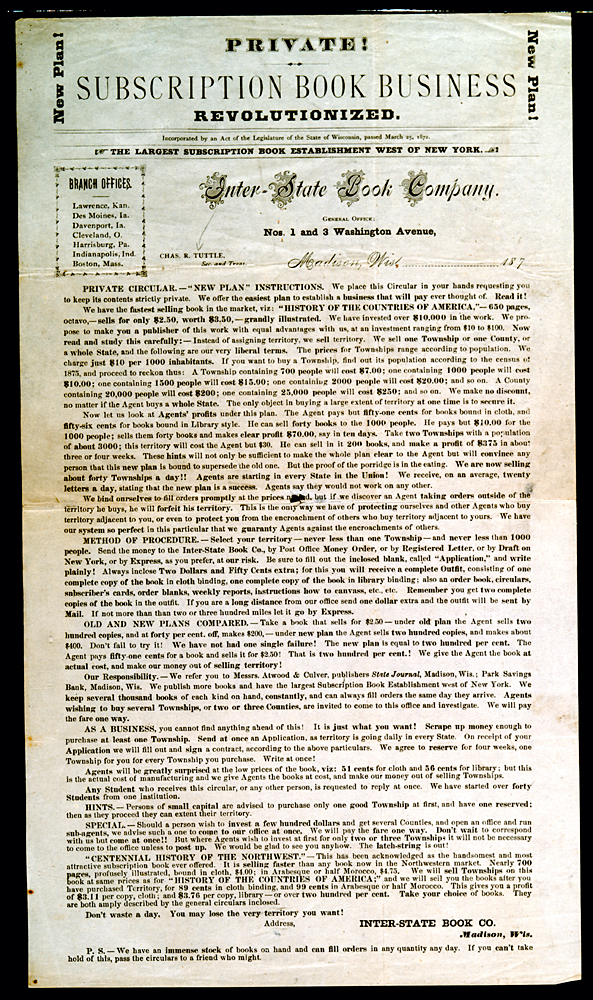

Fig. 7: This circular emphasizes that it should be kept private, perhaps to keep prospects from deconstructing the argument by discussing its merits and defects with others. Rather than assigning agents to a specific territory, the "New Plan" advertised here requires agents to "buy" a territory to canvass. Territories cost anything from ten to one hundred dollars, or even more. The argument is that the agent becomes a publisher, investing in a territory, and that profit potentials are greatly increased since agents pay only for a book's manufacturing cost. Knowing-as we do now-that many, and perhaps the majority, of agents never earned a cent, or even went into debt, from canvassing, the proposal seems a questionable investment. The "New Plan" does not seem to have been successful. Later advertisements for agents often emphasize that agents need not commit their own capital.

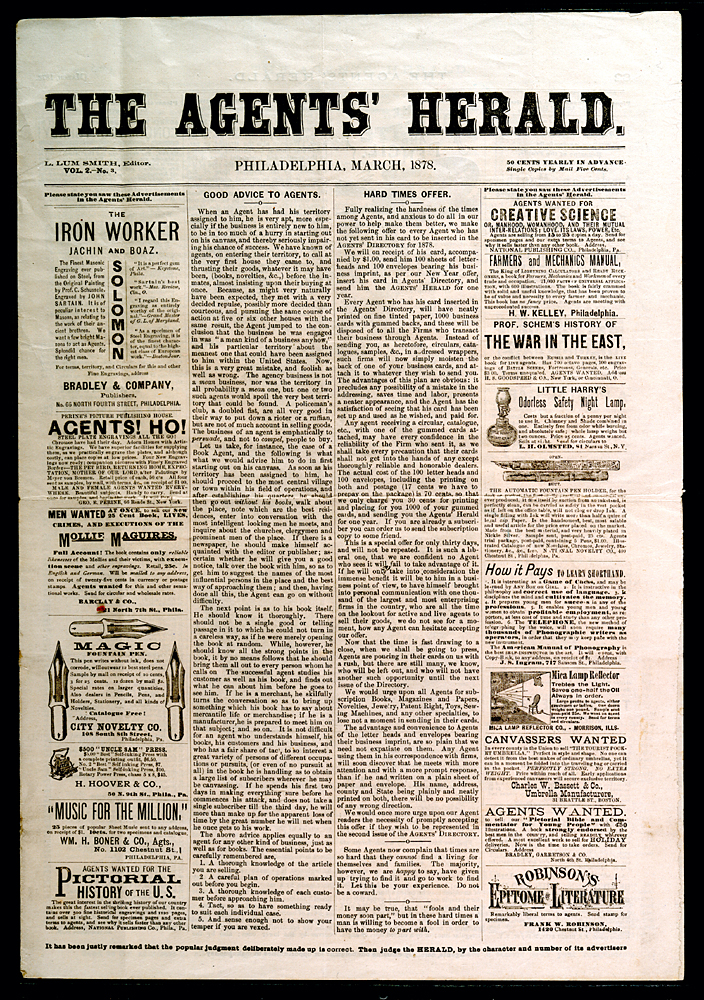

Fig. 8: The Agent's Herald was directed specifically at agents and agent wannabes. Published on South Eighth Street in Philadelphia from 1877 to the late 1890s by Lum Smith, it advertised a range of items to be canvassed, from books and magazines to pant stretchers and electric belts. Smith's ethics may not have been entirely pure. He supposedly threatened manufacturers and publishers unwilling to advertise in The Agent's Herald with bad press. But he also fought on behalf of agents, advocated free trade among the states and territories, and published important legal opinions that affected the ability of agents to practice their profession.

Which exhibit?

Page: Featured item

Short name for this entry

intro

Order on exhibit page

0

Turn off the details link on the exhibit page

On

Exhibit sub-tab