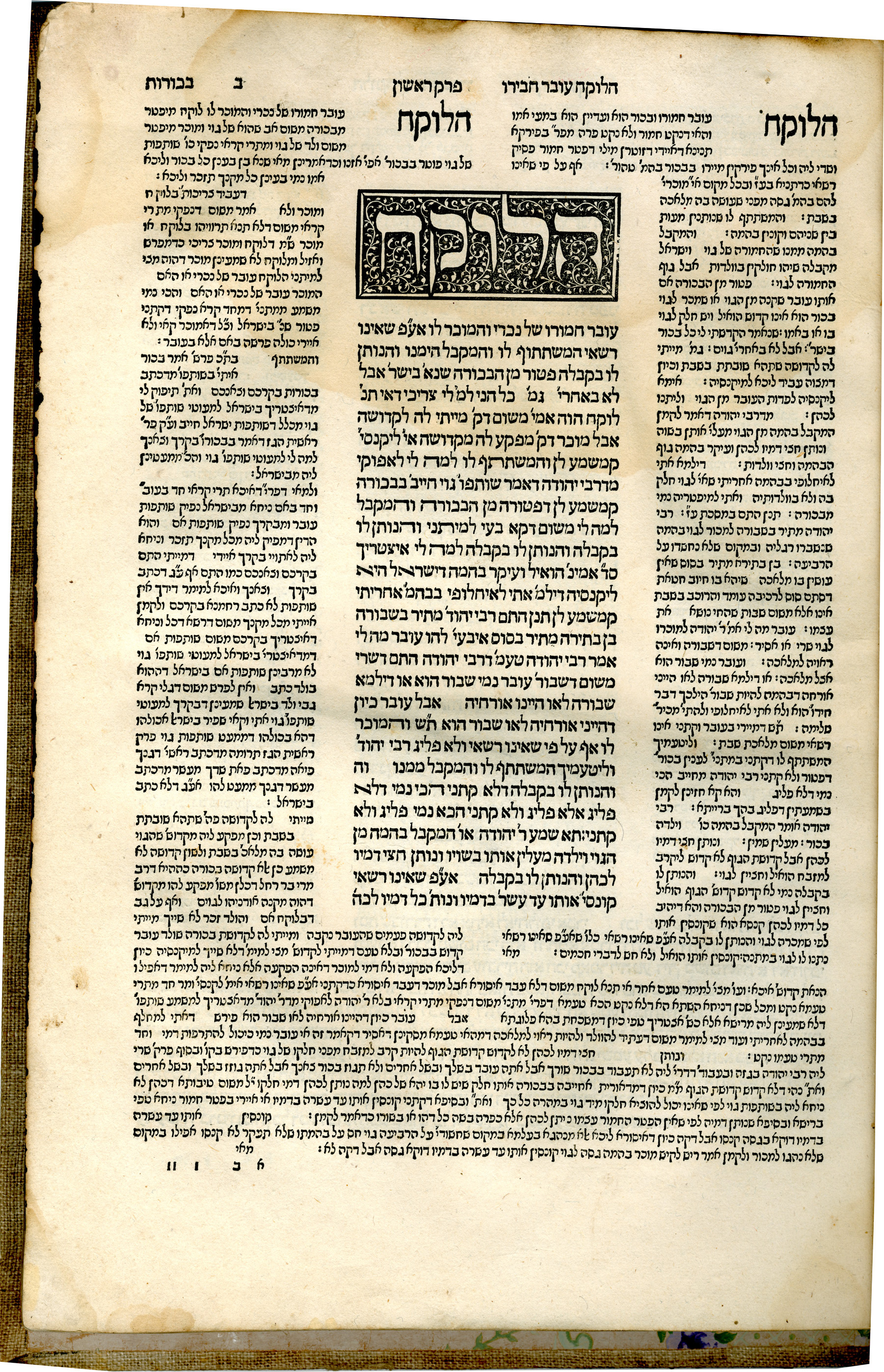

The copy of Tractate Bekhorot included in this exhibition is one of the volumes of the first complete edition of the Talmud, printed in the printing house of Daniel Bomberg in Venice between 1520 and 1523. Bomberg's edition had a huge impact on the use and study of the Talmud. The page layout introduced in the Venice printing has been preserved in virtually every subsequent printing of the Talmud, including the famous Vilna edition and the recent Schottenstein edition. This is no accident. The advent of printing changed the way in which citations to the Talmud are given. During the manuscript era, scholars would refer to a specific Talmudic discussion by its name and the name of the chapter in which it appeared. After the printed editions took hold, it became possible to give a much more precise reference to the page within the tractate on which the source appeared. The popularity and wide distribution of the Bomberg edition led its page numbers to become the universal standard.

The significance of the Venice printing is not only in the text of the Talmud, but also in what it added to the Talmud which would with time become an integral part of the text

Finally, the layout of the printed page of the Talmud could be considered a further chapter in a thread of Jewish history which began with the Mishnah edited by Rabbi Judah the Patriarch in the Galilee in the third century, and continued with the Talmud itself which was created in Babylonia from the third to the fifth centuries. Rashi's commentaries were written in the eleventh century in the Franco-Ashkenazic cultural sphere, since Rashi himelf was born in France and educated in the academies of Germany. The Tosafot were written in that same area, principally during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Thus, the printed Talmud page brings together multiple generations of the Jewish people who in all their wanderings continued to devote themselves to the study of Talmud.