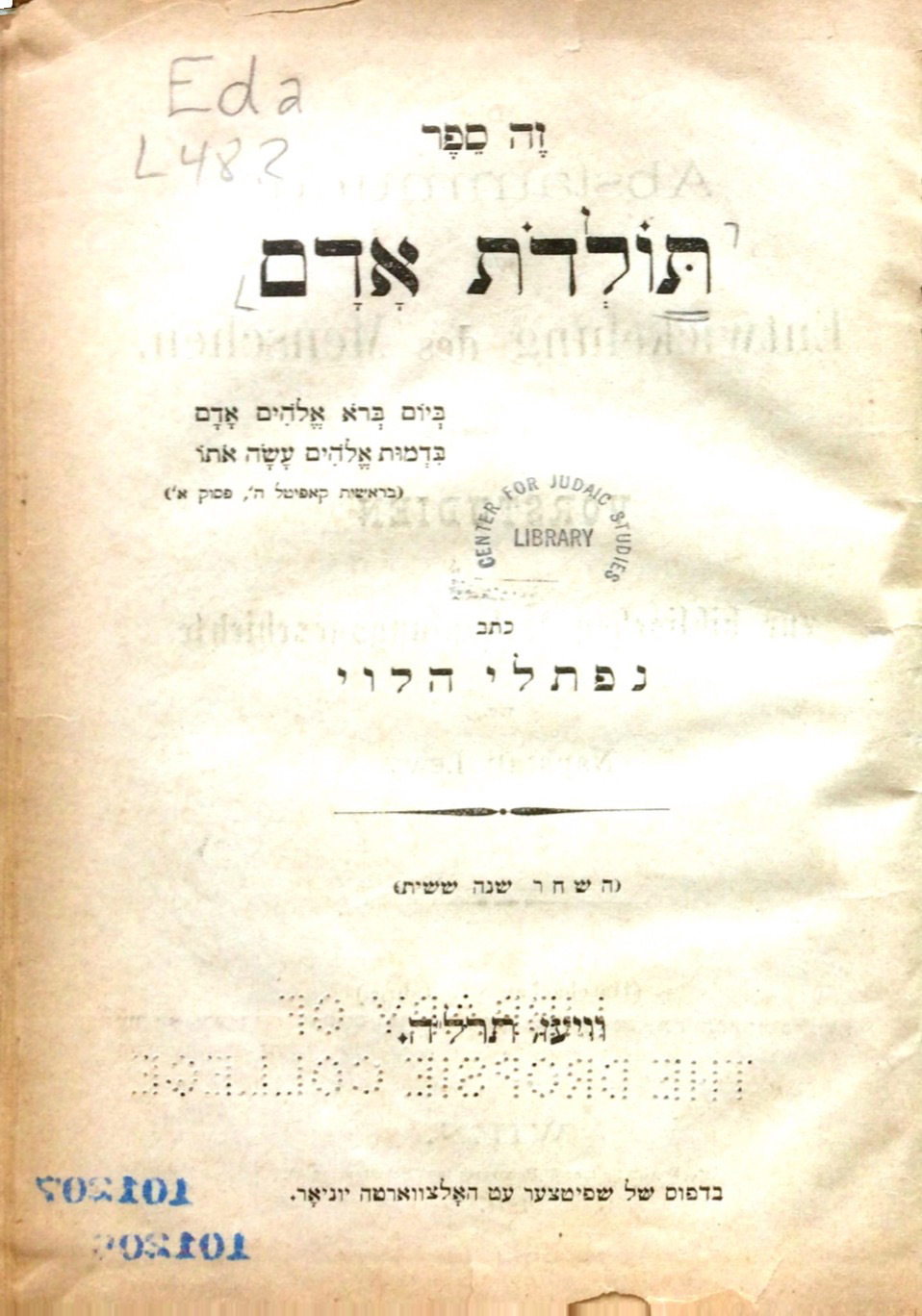

Naphtali Levy (1840-94) has an important place in our story since he is that rare thing, an ostensibly orthodox Jewish thinker enamoured of Darwin, and since he was the first to translate excerpts from Darwin’s writings into Hebrew in his study Toldot Adam [The Origins of Man] (Vienna: Spitzer & Holzwarth, 1874), 60pp..

Born in Kolo, Poland, Levy was the son of a dayyan or religious judge and received a traditional religious education (with teachers including Meir Auerbach, who was later the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Jerusalem) until he moved to Posen for secular studies in science and modern languages, when he became interested in the Haskalah or Jewish Enlightenment. From 1860-67 he earned his living as a tutor for a wealthy family and as a merchant in Radom, Poland, and it was while there that he wrote Toldot Adam, originally publishing it in the Haskalah journal Ha-Shachar (The Dawn) in 1874. In 1877 he moved to London where, after unsuccessful careers as a newspaper editor and as a boot manufacturer, he was appointed as shochet or ritual slaughterer for the London Board of Shekhita, a position which he held until his retirement in 1892. He wrote other works on halakhic matters, but never again on science.

In any examination of the 34 year-old Levy’s six-chapter, sixty-page book on Darwinism, one should bear in mind that it was not a sombre, systematic treatment, but was exuberant in style and highly apologetic in nature. The author had had an exciting new world opened up to him through reading The Origin of Species in German translation

The main focus of Toldot Adam is to be found in the fourth and fifth chapters in which were presented the key challenges to received religious tradition. Here Levy outlined how all of life was connected through evolution, from plants to animals to humans. This was hinted at in rabbinic texts such as Midrash Rabbah 11 (‘Everything that was created in the six days of creation needs to have something done to it; even man needs improvement’). It was even more clearly indicated by biblical texts such as Genesis 2:6 (‘there went up a mist from the earth, and watered the whole face of the ground’), which taught that the plant life that carpeted the planet had, through its metabolic use of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and nitrogen, made possible the evolution of animals and humans. More than any pious motivation to bring glory to the Creator, it appeared that it was the new scientific awareness of the explanatory power of natural laws that caught Levy’s imagination. For example, in discussing the emergence of hominids, he portrayed natural selection as a natural force working in harmony with the divine will to improve the stock of humanity. God’s contribution was indirect or even secondary, in that He was understood to have changed the environment in which humans were located and this migration, according to evolutionary theory, allowed natural selection to generate new adaptations. (According to Levy’s reading of Genesis 2:8 [‘and God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man he had formed’], God had formed man in the west and later moved him east to Eden.)

It would be mistaken to see the young Levy as a traditionalist offering nothing more than an evolutionary midrash. At times he offered speculations uncharacteristic of one espousing an Orthodox religious worldview. For example, in contrast to other Jewish evolutionists who rejected the apparent cruelty and chance of natural selection, Levy’s God reigned over a natural world undeniably shaped by the darwinian ‘struggle for existence’; in fact it was from this suffering that morality could evolve. And he occasionally let slip, writing of Nature’s command ‘Let there be light!’ and even suggesting that the image of an ape-like hominid was a more accurate portrayal of the first man than was the biblical claim of divine likeness. In a short appendix, Levy also discussed the future evolution of mankind, expressing the hope that one day man would no longer die, and even the possibility that there would arise other creatures, higher still on the ladder of life than humans.

He continued to write, but never again on the subject of evolution; other publications included a miscellaneous collection entitled Hikre Kadmoniyot (Researches in Antiquity, 1862), an exposition of the laws relating to the fifth commandment, Hilkhot Kibbud Av va-Em (Laws Honouring Parents, 1883), dissertations on legal and homiletic subjects entitled Kadesh Naftali (Naphtali’s Sacred Things, 1891), and Nakhalat Naftali (Naphtali’s Inheritance, 1892), which included an historical account of rabbis in England in the pre-Expulsion period and which listed the Chief Rabbi of Berlin, Israel Hildesheimer, among those authorizing and approving the work. In his final years he moved away from London to Southport for reasons of health and helped establish an Orthodox congregation there.