Many of the works described in this article are now available online via HathiTrust's Emergency Temporary Access Service.

Franklin Catalog records for works now available online have a COVID-19 Special Access from HathiTrust — Login for full text link towards the bottom of the page.

Diversity in the Stacks aims to build library collections that represent and reflect the University’s diverse population.

Rigid hierarchies of caste in South Asia have sanctioned the subjugation and exploitation of so-called “untouchable” communities for centuries. Now frequently referred to by the term Dalit (a word derived from the Sanskrit dalita, meaning “scattered” or “broken”), these oppressed peoples are fighting for greater recognition and equality. The rise of a distinct Dalit literature in the 20th and 21st centuries has helped raise awareness of the Dalit experience, thereby spurring political movements and social activism.

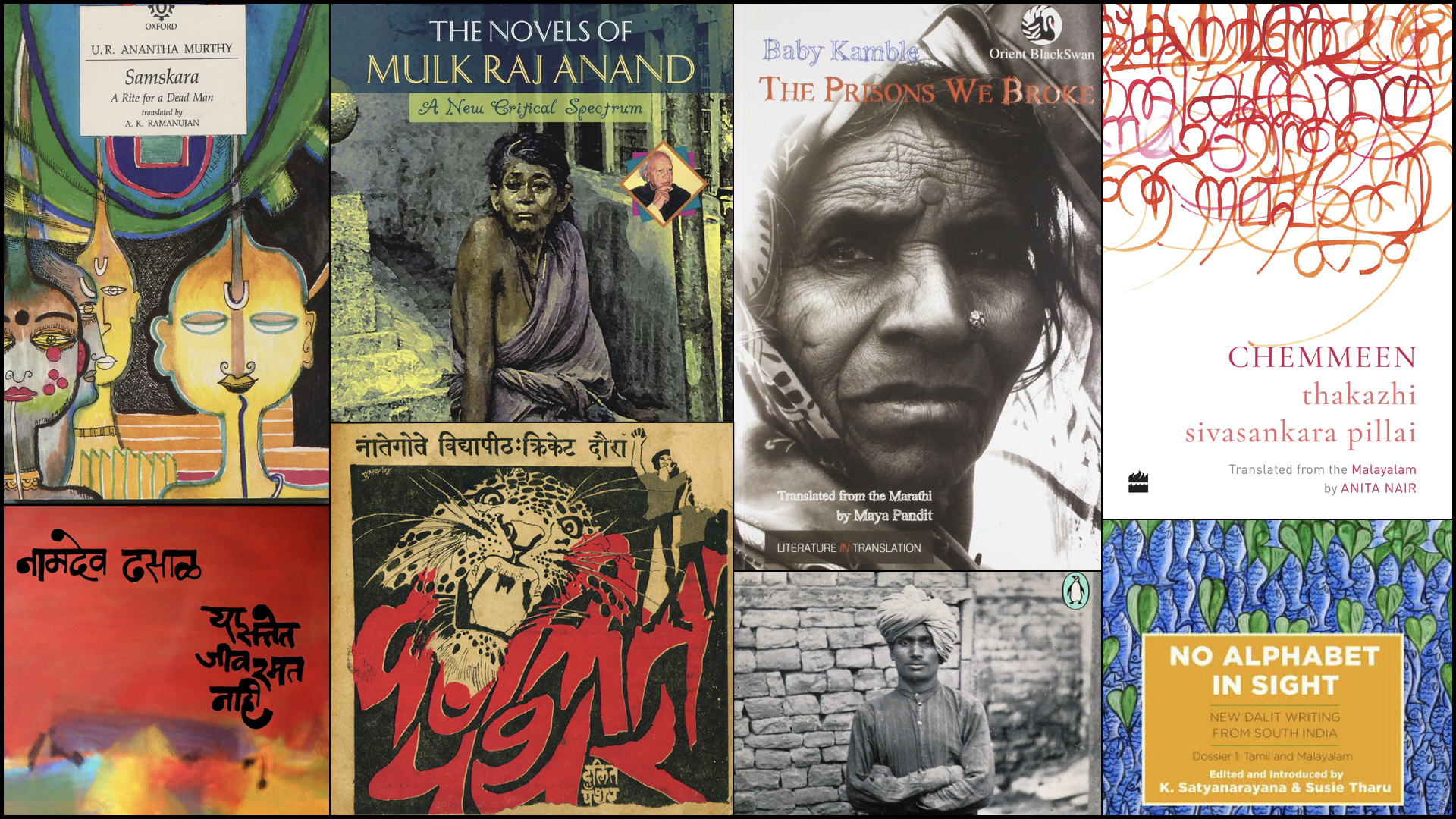

Works of non-Dalit writers — such as Mulk Raj Anand, Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, Munshi Premchand, and U.R. Ananthamurthy — offered harsh critique of the status quo in 20th-century India, frequently presenting Dalit characters with sympathy and compassion. In the late 1960s, however, Dalit writers themselves began to chronicle their own experience, particularly in the state of Maharashtra. The influence of earlier political reformers Jyotirao Phule and B.R. Ambedkar, along with the rise of the revolutionary Dalit Panther movement in the region, fueled literatures of protest, struggle, and resistance.

With Maharasthra as its locus of origins, early Dalit literature was largely composed in Marathi. Baburao Bagul’s fictional writing presented graphic accounts of the lives of the marginalized and downtrodden, causing a stir amongst Indian literati. Namdeo Dhasal, one of the founders of the Dalit Panthers, composed numerous collections of poetry that shocked middle-class moralities with imagery of blood and fire as well as extensive use of obscenities.

Autobiography also became an especially popular genre of Dalit literature; the memoirs of Baby Kamble (Jīṇā Āmucā, translated into English as The Prisons We Broke) and Urmila Pawar (Aidan, translated into English as The Weave of My Life) provided first-hand descriptions of the daily lives of Dalit women, exposing the ways in which caste and gender discrimination oppress them.

In the late 1980s and into the 1990s, Dalit literature began to expand more significantly into other South Asian languages. Life writing continued as a popular form of Dalit expression, demonstrated by Bama’s Tamil autobiographical novel Karukku about life as a Dalit Christian woman, as well as by Kausalya Baisantry’s Dohra Abhiśāp, the first autobiography of a Dalit woman published in Hindi.

Poetry also continued as an especially vibrant means of revealing Dalit experience and identity. Mudnakudu Chinnaswamy’s Kannada collections, Raghavan Atholi’s compositions in Malayalam, and Sukirtharani’s Tamil writings have all dramatically impacted both the literary and political spheres.

Apart from a few scattered examples, such as two collections of English translations from Marathi, Poisoned Bread and A Corpse in the Well, Dalit literatures were largely limited to regional, native-speaking audiences before the 2000s. In recent years, however, an explosion of English translations has broadened the reach of Dalit writing throughout South Asia and beyond. The popularity of works such as Gail Omvedt’s translation from Marathi of Vasant Moon’s Growing Up Untouchable in India; Arun Prabha Mukherjee’s translation of Omprakash Valmiki’s Joothan; and Narendra Jadhav’s own rendering of his Marathi work into the English version Untouchables has helped raise awareness of caste struggle across the world. Additionally, substantial anthologies of translations, such as No Alphabet in Sight and Oxford anthologies of Dalit writing in Malayalam, Tamil, and Telugu, are providing ever increasing access to previously unheard voices.

With Hindutva nationalism on the rise in India, awareness of caste oppression and the advancement of Dalit equality remain vitally important. Building a collection of Dalit writings at Penn Libraries contributes to that mission by supporting the research and learning of our community. In featuring caste diversity, we aspire to broaden understanding of Dalit identity and influence positive social change.

Rigid hierarchies of caste in South Asia have sanctioned the subjugation and exploitation of so-called “untouchable” communities for centuries. Now frequently referred to by the term Dalit (a word derived from the Sanskrit dalita, meaning “scattered” or “broken”), these oppressed peoples are fighting for greater recognition and equality.